- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

The Timber Pagoda of Yingxian as a Conceptual Emanation of the Vairocana Buddha

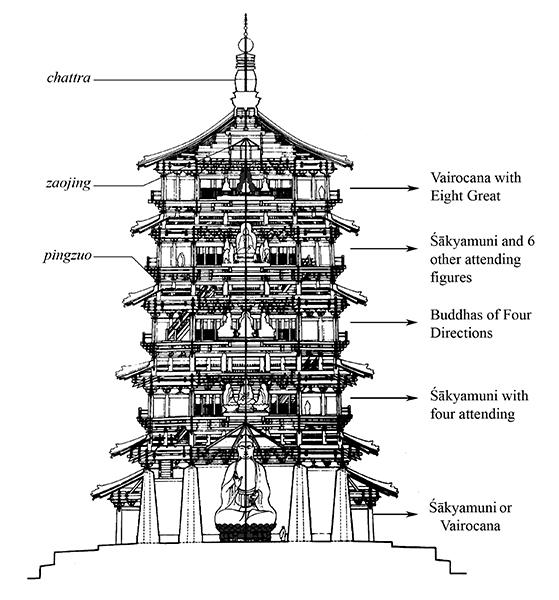

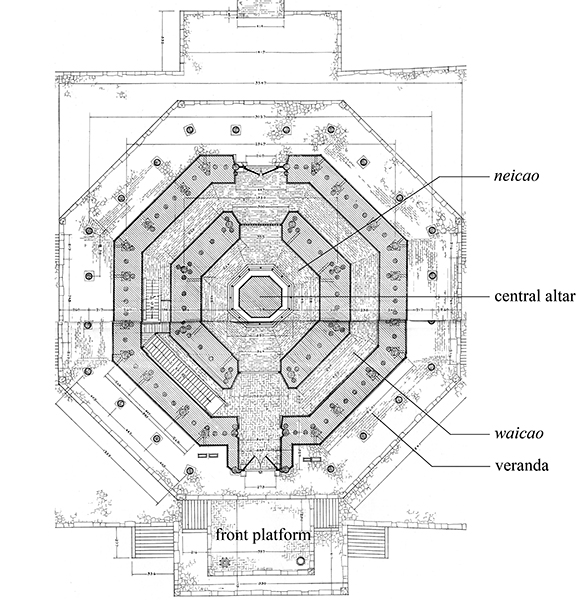

Close to the architectural style of the White Pagoda in Qingzhou and the Rotating Sutra Cabinet is the eight-sided Timber Pagoda (Muta 木塔), built in 1056 at the Fogong 佛宮Monastery in Yingxian, Shanxi (fig. 25a).[93] Structurally, however, the Timber Pagoda is more similar to the Guanyin Pavilion (fig. 14); both contain a true multistoried interior that one can enter and ascend. The tallest and oldest surviving wooden pagoda in China, the Timber Pagoda has five interior stories, and a mezzanine level that serves as the pingzuo was built between every two stories. All five interior stories have a similar octagonal structure, with two interior rings of columns that define an outer aisle (waicao) built with flights of stairs and a central area (neicao) that contains the sanctum and enshrined images (fig. 25c). Each story features an elaborate set of the iconic group on a raised, octagonal platform located at the center, together providing five different emanations of the Buddha in an interconnected series as either the Vairocana or Śākyamuni Buddha (fig. 25b). On the first level, sitting on a throne of lotus petals, is an oversized Śākyamuni Buddha, although its identity has been debated, an issue to which I will return. The second level features the Śākyamuni Buddha attended by four bodhisattvas. The third level is the hall for the Buddhas of the Four Directions. The fourth level has a set of seven statues with the Śākyamuni Buddha at the center. At the fifth level, the Vairocana Buddha is surrounded by the Eight Great Bodhisattvas. The interpretation of the iconography in the pagoda has been a point of discussion.[94] I contend, however, that we cannot fully understand the iconographic program without considering the agency of the multilevel pagoda: how it structures the iconography as part of its religious mechanism and how it engages visitors.

If we focus on more than the Buddhist statues, we begin to see how vigorously the multilevel structure intervenes in the reading and experience of the iconography. At first glance, the wooden structure that contains the statues is definitely different from the crypts in the brick pagodas, in regard to religious function and aspiration. A close look changes that initial impression. Inside the pagoda, all five iconic sets enshrined in the most central area of their respective floors are aligned perfectly along the central axis, around which the iconographic program and architectural space revolve. In a sense, interior floors of the Timber Pagoda resemble the crypts inside the brick pagodas, evoking and facilitating a vertical rise along the central axis.

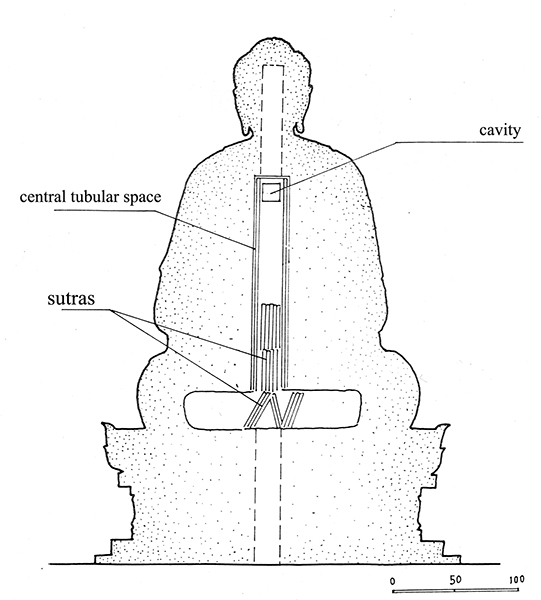

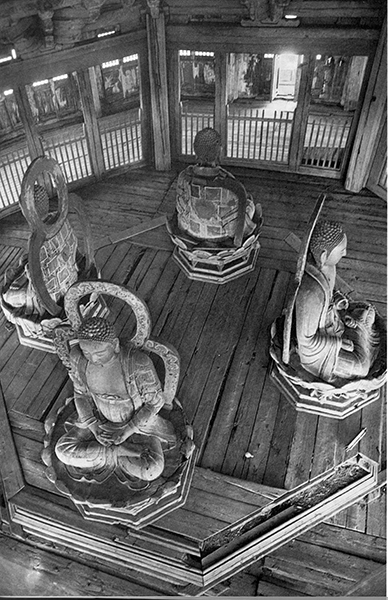

The resemblance does not end there. Although it has no interior crypts, the Timber Pagoda incorporates the sacred depository in a less conspicuous yet equally effective manner. Each of the sizable statues of Śākyamuni on the second and fourth levels contain sacred items inside the torso; the one on the second level has a cavity with relics in a silver case, while the other has a tubular space (fig. 26) built with wooden boards that stores more than 160 objects, mostly sutra scriptures, i.e., dharma relics.[95] With these relics, the two Buddhist statues—the main images of their respective iconic sets—should also be regarded as reliquaries, whose hollow interiors are aligned with and thus comprise part of the pagoda’s central axis. Interestingly, on the third level, the Buddhas of the Four Directions, each facing its respective cardinal direction, physically enclose a central empty space (fig. 27). As explained earlier, having the four directional Buddhas represented on the exterior of the multilevel pagoda implies the absence of the Vairocana Buddha in the center. Indeed, the empty center is essential in locating the structure’s vertical centrality, which conceptually extends into the hollow interior of the statues and throughout the entire pagoda. Eighteen scrolls of Lotus Sutra were included in the interior depository of the statue on the fourth level, further affirming that the pagoda is the dharma-body realized by the Vairocana Buddha. This realization, nevertheless, is more critically manifested through the architecture of the pagoda.

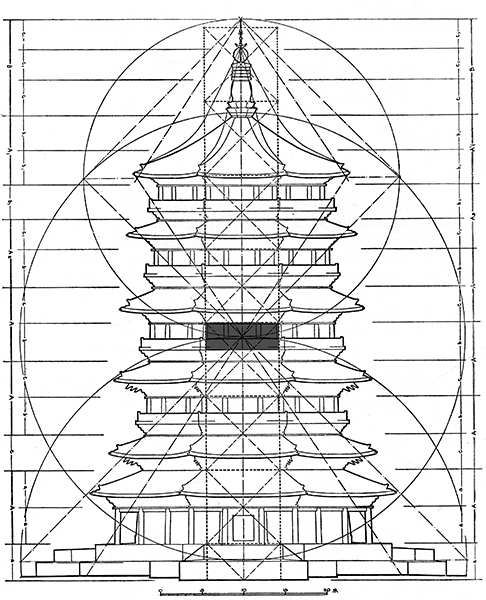

In his research on the Timber Pagoda, published in 1980, the eminent Chinese architectural historian Chen Mingda 陳明達suggested that a module unit had been used in the timber-frame structure and that it decided the pagoda’s front elevation. Accordingly, we measure the height of the pagoda against the width of the third floor between the two outer eave columns. Calculated from the front elevation, the same floor is also the converging point of various proportional relationships among different building parts (fig. 28).[96] In this light, enshrining the four directional Buddhas on the third level must have been a deliberate design choice, and the Vairocana Buddha, while not physically represented, is the center that unifies the entire pagoda, in both religious and architectural terms.

Now, let us return to the iconography of the pagoda. The colossal Buddha on the first floor has been recognized as the Śākyamuni Buddha given the fact that images of six equally gigantic Buddhas appear on the six interior walls (fig. 29). Together, the seven Buddha images on the first floor refer to the preceding six previous Buddhas and the Śākyamuni Buddha at the center, called Seven Buddhas of the Past (saptāṅgavidhi).[97] In her 2001 article, Hsueh-man Shen, however, identifies the central statue on the first floor as the Vairocana Buddha based on the throne of lotus petals (fig. 30), each of which is painted with a small Buddha image, representing the numerous coexisting worlds revolving around the Lotus Petal Treasure World (Lianhuatai zang shijie蓮花台藏世界) where the cosmic Buddha presides.[98] Either identification makes sense, but neither one interprets the icon with the building structure in mind. When considered only on its level, the colossal Buddha flanked by the six past Buddhas painted on the walls is likely to be Śākyamuni. But if one takes the pagoda as a whole with its heart at the third level, the main icon on the first floor, which is now only part of the entire iconographic program, should be identified as the Vairocana. This identification echoes that of the Vairocana Buddha on the fifth floor, accompanied by the Eight Great Bodhisattvas, so identified with its protruding topknot or crown (ding 頂, or uṣṇīṣa), indicative of the superior wisdom of the supreme Buddha (fig. 31).[99] If we take all the iconographic elements together, the pagoda can be conceptualized as the ultimate emanation of the Vairocana Buddha’s dharma-body, manifested via the iconic sets and rising from the lotus seat on the first level through the central axis of the second, third, and fourth levels up to the topknot of the Vairocana statue on the fifth level under the sunken ceiling (see fig. 25b).

This conceptual Vairocana, however, would not have been revealed to visitors in ways that have been explained here. In addition, Liao visitors could not use a diagram, such as the frontal section in figure 25b, to guide their visit. Yet upon entering the pagoda, visitors immediately would be prompted by the flights of stairs built in the aisle on all five levels to ascend, clockwise as if in circumambulation, while observing the five sets of icons in a continuous sequence. It is worth noting that while the stairs were built on the non-cardinal sides, alternating between levels to evenly distribute the weight they create, only those leading to the third level take the visitor to the south (front) side of the altar.[100] Emerging from the stairwell to the third level, the visitor would come to the front of the Buddhas of the Four Directions and venerate them face to face, thereby contemplating as well as enacting all the multivalent significance of the absent space they enclose at the very center of the pagoda.

Animation shows the five sets of icons aligned vertically along the central axis of the structure that can be observed in a continuous sequence as one ascends the pagoda clockwise in circumambulation. SketchUp model built by Zhenru Zhou.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.