- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

Two Acts of the Pagoda: Iconography and Ritual

To a great extent, the two aforementioned features—the multilevel structure and the vertical axis—use the same vocabulary, although one is exterior, visible, and physical, while the other is interior, hidden, and conceptual. Beginning in the late Tang dynasty, two more factors became important. First, the content of the depository in interior crypts became richer and more elaborate. In addition to physical relics, it grew to include ritual and devotional items, which complicated the nature of the pagoda and the ways in which it worked as a ritual center.[64] Second, the pagoda was clad with more sophisticated iconography, such as those in the Liao territory built with relief images that in effect dress their exteriors.[65] Both the interior and exterior of the Liao pagodas have been topics of research in the past ten or so years. It has been suggested that the key to understanding the specific symbolism and ritual function of the Liao pagoda lies in the correlation and intercorrelation between the exterior and interior.[66]

While I am indebted to this scholarship, my purpose here is to explore how the multilevel pagoda acts out its symbolism and function. I will treat iconography and ritual as two religious “acts” or events that provide a specific context in which the pagoda engages and communicates with the visitor. Through these acts, we shall observe the multilevel pagoda—its components and characteristics (i.e., exterior/interior and level/elevation)—performing as a “structured mechanism” that acts out its symbolic and ritual functions to the visitor.

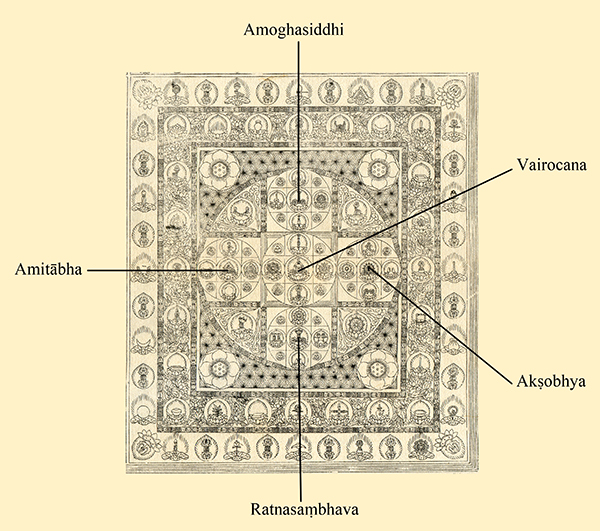

Let’s start with the iconography. The set of icons that appears most conspicuously on the exterior of many pagodas from the Liao period is known as the Buddha of the Four Directions (sifangfo 四方佛).[67] The four Buddhas refer to the Ratnasaṃbhava (Baosheng 寶生) Buddha in the south, Amitābha (Amituo 阿彌陀) Buddha in the west, Amoghasiddhi (Bukong chengjiu 不空成就) Buddha in the north, and Akṣobhya (Achu 阿閦) Buddha in the east, as seen on the four exterior walls of the North Pagoda (figs. 17a–b) in Chaoyang 朝陽, Liaoning, dated to 1043–44. Made entirely in brick, the four-sided pagoda has an elevation typical of the Liao pagoda of this period, consisting of a tall base, shaft, and a series of close-set eaves (miyan, usually thirteen in total), ending with the finial.[68] The image of each Buddha is prominently carved on the side of the shaft facing the cardinal direction with which the Buddha is associated. The four directional Buddhas on the exterior also demarcate the central position, evoking the Vairocana Buddha at the very center; together, the group comprises the Five Wisdom Buddhas (wuzhi rulai 五智如來, or pañcatathāgata) that constitute the Diamond World Mandala in the tantric tradition.

Considered with this iconographic scheme, the Chaoyang North Pagoda may have been built to realize the mandala in architectural form, with the pagoda itself representing the Vairocana at the center.[69] This is supported by the schematic diagram of the mandala. In the Samaya Assembly of the Diamond World Mandala, the Vairocana Buddha is represented at the very center with the emblem of a pagoda (fig. 18).[70] In this light, the secret center of the pagoda evokes not only the rise along the axial elevation but one related to the centrality and interiority of the Vairocana Buddha, whose eternal and unchanging body symbolizes the true teaching (dharmakāya); it is invisible and formless but equated to the entire cosmos.[71] It is then only logical to find some evidence of the Vairocana Buddha represented inside the pagoda.

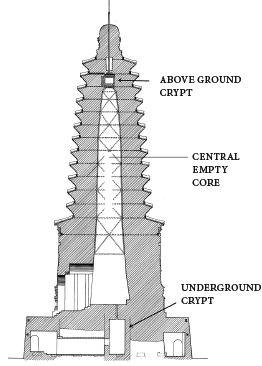

In 1988, a stone crypt was found inside the twelfth eave of the Chaoyang North Pagoda (see fig. 17b) with a great number of treasures, including relics of different forms, ritual accoutrements, and devotional objects. Of the iconographic components inside the upper crypt, the most important one is a mandala of the Vairocana Buddha surrounded by the Eight Great Bodhisattvas (bada pusa 八大菩薩, or aṣṭa-upaputra) carved on the north (main) wall.[72] Although the details of the central Vairocana are not completely decipherable, as Youn-mi Kim suggests in her thorough study of the pagoda, a gold plate from the crypt depicts a similar mandala, in which the central deity is clearly identified as the Vairocana Buddha with the vajra-mudrā (zhiquan yin 智拳印), i.e., the left-hand index finger encased in the right fist (fig. 19).[73] The canonical source for the combination of the Vairocana Buddha with the Eight Great Bodhisattvas in a mandala is likely the ritual manual (yigui 儀軌) devised for reciting the Superlative Dhāraṇī of the Buddha’s Crown, translated and redacted by Amoghavajra in 764.[74] In the manual, the Vairocana Buddha is called upon specifically to reside at the center of the mandala. In other words, the Vairocana Buddha inhabits the center of two concentric mandalas: one with the four directional Buddhas on the exterior and the other with the Eight Great Bodhisattvas in the interior.

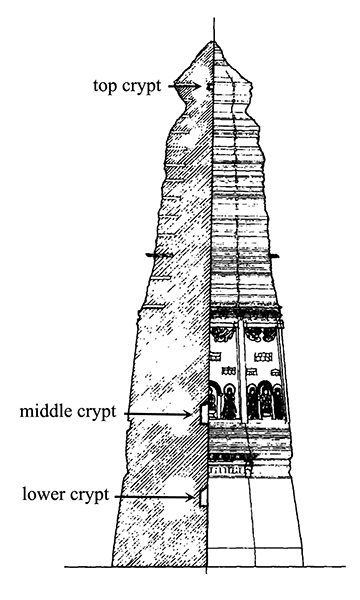

As it turns out, the four directional Buddhas and Eight Great Bodhisattvas are among the images most frequently seen on the exterior of pagodas, in particular, the octagonal ones from the Liao territory.[75] And either of the iconic sets on the exterior needs the Vairocana Buddha as the conceptual center of the pagoda to be complete. A useful example in this regard is the Liaobin 遼濱Pagoda, built in 1114, in modern Xinmin, Liaoning.[76] An octagonal structure (fig. 20), the pagoda also has a base, central shaft, and thirteen closely piled eaves, typical of the Liao pagoda around this time. Each of the eight sides has a Buddha inside a niche; the four niches on the cardinal sides are flanked with images of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas. Inside the structure are three evenly distributed aboveground crypts aligned along the central axis. Most significant, both the lower and middle crypts were set up as ritual spaces, with reliquaries and other ritual objects (e.g., incense burners, rosary, banners, and others) on an altar table. Inside the lower crypt, the altar is placed in front of an image of the Vairocana Buddha in brick relief (fig. 21), the object of ritual veneration.[77] Installed at the center of the pagoda, the relief image inside, otherwise invisible from outside, materializes the very presence of the Vairocana Buddha, whose power could potentially be called upon in a ritual. The iconography deployed throughout provides a ritual context in which the pagoda’s interior and exterior components are not simply correlated in architectural terms but act out that iconographic significance, for the building’s symbolism and ritual functions cannot be fully enacted without each other.

One issue, however, arises in regard to the crypt as a ritual space. With an area of less than one square meter and a height of only 1.05 meters, the lower crypt of the Liaobin Pagoda likely was not intended for actual rituals; sealed from outside, the crypt would not have allowed people to enter. What, then, was the purpose of creating a ritual space inside the pagoda? Youn-mi Kim raises a similar question about the crypt of the Northern Pagoda in Chaoyang. Inside its upper crypt (fig. 17b), measuring 1.14 by 1.17 square meters with a height of 1.26 meters, there is a mandala of the Vairocana Buddha with the Eight Great Bodhisattvas engraved on the north wall. One wonders for whom this mandala was prepared, if it were to be used in a ritual as instructed in the manual for reciting the Superlative Dhāraṇī of the Buddha’s Crown. Not coincidentally, two sets of the very dhāraṇī to be recited during the ritual were also found in the crypt. Accordingly, Kim has persuasively argued that the crypt may have been a self-perpetuating ritual space, for certain Buddhist ritual devices, including the mandala and dhāraṇī, could remain efficacious even in the absence of human actors. In a sense, concealed from without, the crypt—installed as a secret ritual arena—transformed the pagoda into a virtual, eternal mandala of the Superlative Dhāraṇī of the Buddha’s Crown that itself performed the salvific power accorded to the ritual.[78]

This argument is suggestive. Still, the crypt is but one part of the “structural self” of the multilevel pagoda. That is, if we take into account the performative potential of the pagoda’s multilevel structure, the agentic power of the building may supplement the lack of human agency inside the crypt.

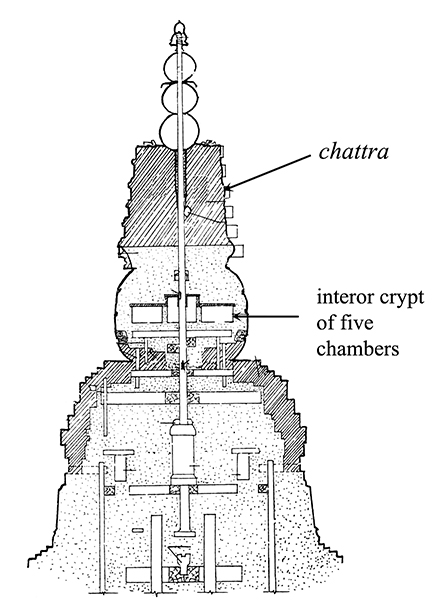

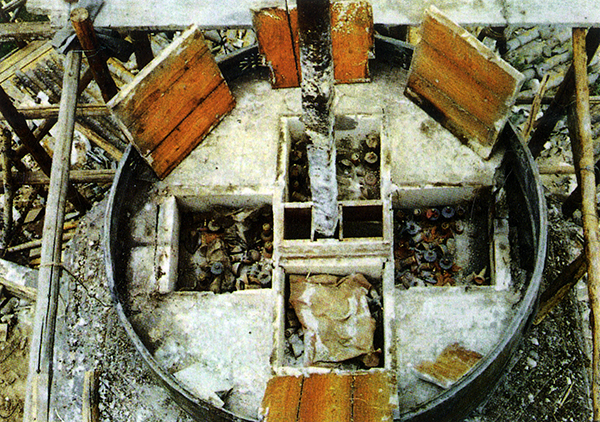

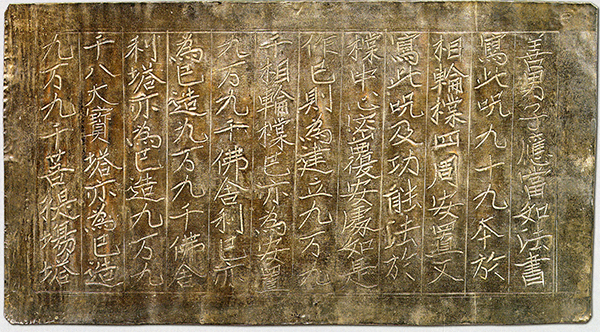

An example in this regard is the White Pagoda in Qingzhou 慶州 (fig. 22a), built in 1049 in present-day Balin Right Banner, Inner Mongolia.[79] The White Pagoda is an octagonal brick structure, consisting of a double-level base, seven stories, and a chattra. In the louge style, the brick pagoda, constructed with details that imitate the timber-frame architecture, tapers upward through stories, each of which, except for the first floor, has a distinct pingzuo and a ring of eaves. Inside the pagoda is a solid core that contains several unconnected aboveground crypts at heights that correspond to the exterior levels. All interior crypts yield relics, but most of those in the sacred depository would be found only after someone climbed the entire height of the pagoda and reached the five-chamber aboveground crypt located in the midsection of the chattra (fig. 22b). Contained within the five chambers, one at the center surrounded by four others in the four cardinal directions (fig. 22c), were sutra scriptures, dhāraṇī texts, offerings, and ritual banners. Most significant, more than a hundred miniature pagodas were enshrined in the four flanking chambers, each encasing a copy of the dhāraṇī with the title Dhāraṇī Inside the Cavity of the Chattra.[80] The purpose of the miniature pagodas is indicated in an inscription incised on a silver sheet inside the central chamber (fig. 23). It instructs the pious to enshrine ninety-nine copies of the dhāraṇī inside the cavity of the chattra (xianglun tang 相輪樘); in return, they will receive merits ten thousand fold. The inscription thus should be read as a self-referential instruction for depositing the dhāraṇī at such an elevated position. The instruction incised on the silver plate, however, is only partial. In fact, the inscription itself is an excerpt from the Great Dhāraṇī Sutra of Stainless Pure Light, the most popular sutra enshrined in the pagoda crypt during the Liao period.[81] What is not included in the extracted section is what one should do after the installment of the dhāraṇī. According to the sutra, after the dhāraṇī is placed inside the pagoda, anyone who circumambulates the pagoda clockwise, prostrates himself in front of it, and makes offerings with flowers, incense, bells, banners, and canopies will accumulate countless blessings.[82] This ritual veneration at the pagoda, therefore, completes the dhāraṇī rite (tuoluoni fa 陀羅尼法).

The crypt inside the chattra of the White Pagoda was not set up exactly as a ritual space, as were the crypts inside the Chaoyang North Pagoda and Liaobin Pagoda. Yet rather than seeing the interior crypt as the ritual center, I propose that the multilevel pagoda as a whole should be considered a ritual structure. Perhaps more precisely, it is a structured mechanism, the source of spiritual power in the crypt whose building components enable the pagoda to engage the faithful in the performance of the ritual. While the finial contains a merit-gaining device or system, however, it is the ritual circumambulation performed by the faithful, who in effect turn on the pagoda’s mechanism, that enacts its symbolic meaning and salvific power for ritual efficacy.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.