- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

Rising in Elevation: The Pagoda’s Central Axis

The earliest dateable underground pagoda crypt uncovered in China was built in 481, during the Northern Wei dynasty. It is not always clear, however, if axial poles were constructed inside pagodas in this early period, since most aboveground structures did not survive.[52] In comparison with the underground crypt, scholars are much less certain about when aboveground crypts were constructed inside pagodas. Although there might have been precedents from the Tang dynasty, it was not until the tenth century that the inclusion of one or more aboveground crypts in the center of the pagoda structure became widespread.[53] Aboveground crypts, built in addition to the underground one, provided more space for sacred relics. More significant, their inclusion inside the pagoda aligned vertically along the central axis, which altered the manner in which the axial pole was conceived and used.

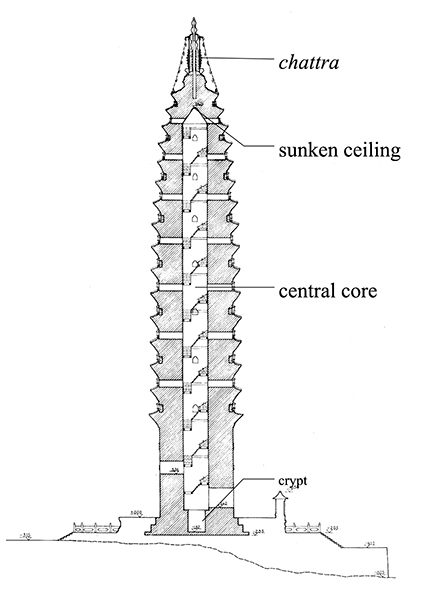

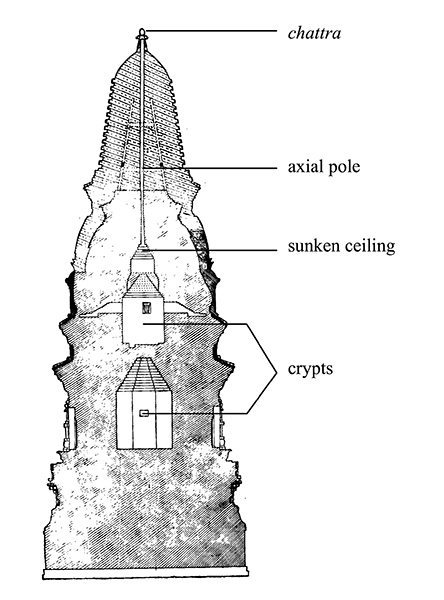

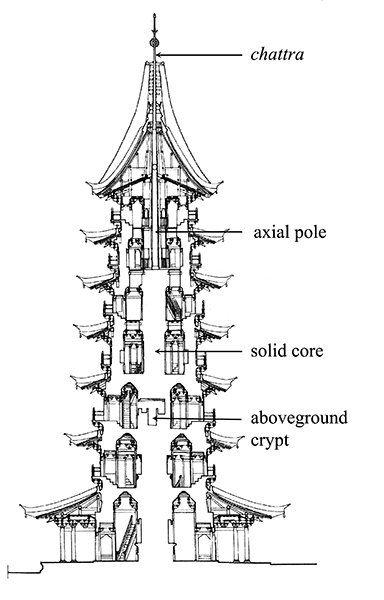

A general survey of the many extant brick pagodas built during China’s Middle Period suggests that there was a consistent structural layout in both the floor plan and vertical section throughout the broader cultural territory of China, encompassing the lands ruled under the Song, Liao, Jin, and, later, Xi Xia.[54] The floor is either a single-ring plan (dancao 單槽) or double-ring plan (shuangcao 雙槽) that contains a central core enclosed by an exterior wall. Its vertical section consists of an underground crypt, central hollow or solid core, aboveground crypts, and the chattra, from bottom to top in a continuous rising elevation.[55] For example, the Qianxun 千尋 Pagoda, built in the late tenth century at Chongsheng 崇聖 Monastery in Yunnan of the Dali State (937–1094), has a hollow core that rises from the crypt in the foundation to the sunken ceiling, which then turns into the basis of the chattra (see figs. 1, 11).[56] Another example built before 1058, the White Pagoda of the Dule 獨樂 Monastery in Jixian, Hebei, has a solid core enclosing two aboveground crypts and an axial pole (which turns into a short finial) built above the sunken ceiling of the top crypt (fig. 12).[57] Similarly, the Ruiguang 瑞光 Pagoda, dated to the early eleventh century, at the Ruiguang Monastery in Suzhou (fig. 13) has a central solid core, around which an interior aisle was built on each level with stairways constructed between. The solid core, which contains a crypt on the third floor, rises to the fifth level and becomes the basis of an axial pole that turns into a chattra.[58] In all these examples—and there are many other variations in structural components or forms of sacred depository[59]—the vertical axis as the sacred and secret center became increasingly complex in both its content and the suggested upward elevation. While the crypt content will be the main topic in the next section, here I will consider the religious significance of the central axis with a slightly different example.

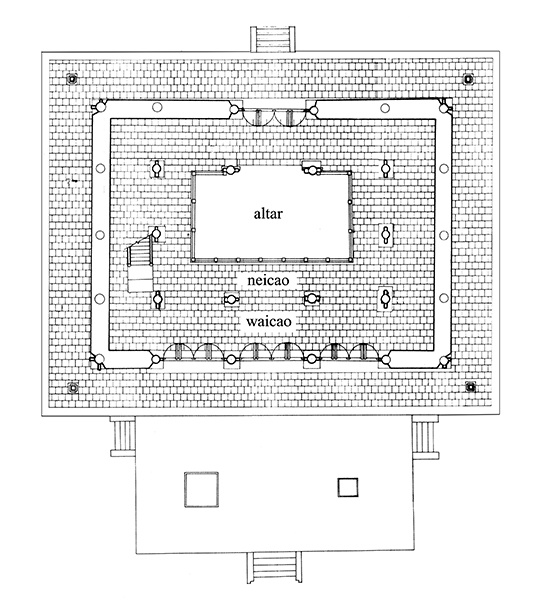

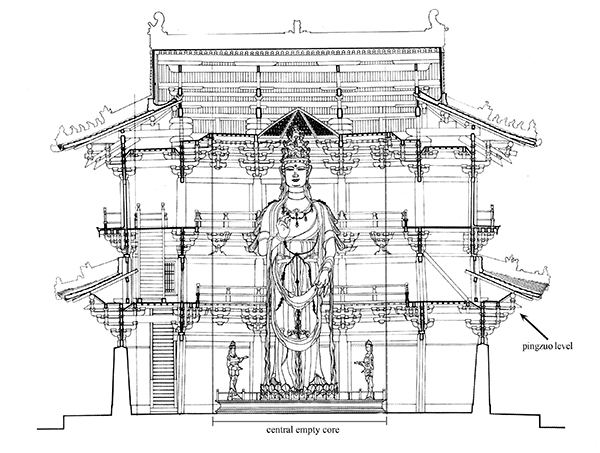

The example, not a pagoda, is the Guanyin 觀音 Pavilion at Dule Monastery (figs. 14a–b), one of the earliest extant multilevel wooden buildings in China, dated to 984.[60] Pavilions are closely related to multilevel pagodas; the two forms share some essential structural and spatial characteristics. The Guanyin Pavilion is a five- by four-bay timber-frame structure, appearing as a two-story exterior with a pingzuo level built inside between the floors. Each of the interior levels has a double-ring plan, with two rings of columns, inner and outer, that form a three- by two-bay central area (neicao 內槽), surrounded by one-bay aisles (waicao 外槽) (fig. 14c). The three interior levels create a central empty core that rises from the ground floor to a hexagonal sunken ceiling (zaojing 藻井) just under the roof structure, not dissimilar to the type of pagoda with a central hollow core. Unlike the pagoda, however, the central space inside the pavilion was structured to fully accommodate a sixteen-meter painted clay statue of the main image, the eleven-headed Guanyin, soaring to the ceiling.[61] Flights of stairs on the right side of the building were built to facilitate the visitor’s ascendance to observe the statue’s towering presence. Anyone who climbs up successive levels traverses the interior space vertically along with the body of the bodhisattva, from its feet to its eleven heads on the top floor (fig. 15). The ascension is revelatory, and thus the central core, whose height is equivalent to that of the sacred statue, is not just negative, empty space; it engages and guides the devotee through the physical structure and enacts the iconography built into the architecture.[62]

Certainly, we cannot ignore the major differences between pagodas and pavilions built with a central core. Most apparent, the pavilion has a functional interior for climbing, while the pagoda’s core is not always accessible. Yet vertically traversing a multilevel building such as the Guanyin Pavilion must have been suggestive to the Buddhist faithful who encountered a towering structure. It has been pointed out that if one stands on the top floor of the Guanyin Pavilion, looking through the window at the statue’s eye level, one can see the White Pagoda (see fig. 12) rising high above the largely horizontal cityscape about 380 meters to the south (fig. 16).[63] The visual connection between the two multilevel buildings was intentional, such that one’s physical elevation through the levels of the Guanyin Pavilion might have inspired a conceptual ascension inside the White Pagoda, through its interior crypts and up to the finial. Height in both buildings, particularly at the moment when they interact with each other, is simultaneously visual, physical, and religious, suggestive of a spiritual ascendance. The vertical axis is therefore more than a marker of a sacred locale or a way of fixing the orientation; it is part of the pagoda’s overall architectonic expression and performance of the multivalent significance embedded in its structure.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.