- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

Introduction

Derived from the Indian stūpa, the Chinese pagoda inherited the stūpa’s original function as an architectural structure that enshrined holy relics, but transformed it into a taller and thinner version.[1] From the beginning, the style and material of the Chinese adaptation varied; it could be four-sided or polygonal and made of timber, brick, or masonry. However, the freestanding, multilevel structure towering above the horizon (fig. 1) has been the most recognizable pagoda type in China’s cultural territory and throughout its building history.[2] It asserts itself in the language of verticality that gloriously manifests Buddhism as a religion deeply entrenched in premodern China, reshaping the physical landscape and reconfiguring its sacred topography as an inseparable part of the building environment and tradition. Yet with its unique form, the sky-high, multilevel pagoda also raises pointed questions about architecture and religion.

In an architectural tradition predominated by timber frames and characterized by horizontal sprawl, building upward was particularly challenging both technically and materially. A higher vantage point is the usual justification for constructing tall buildings such as watchtowers. Elevating viewers to a great height, however, was not one of the multilevel pagoda’s major functions. Furthermore, constructing in materials other than wood was not any easier in a region that rarely needed to deal with the heavier weight of a tall structure that pressed down from above and could cause the building to break laterally.[3] The pagoda’s visual and architectural properties, which seem foreign in contrast to Chinese architectural tradition and vocabulary, thus beg further investigation.

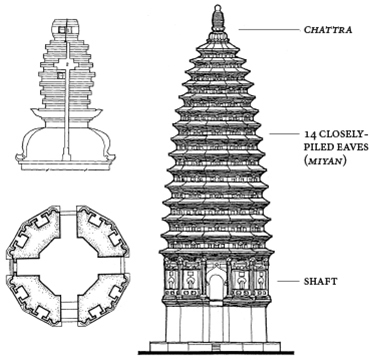

Take the brick pagoda at the Songyue 嵩岳 Monastery as an example (figs. 2a–b). Dated 523, it is the earliest extant pagoda built in the true multilevel style.[4] The twelve-sided structure consists of a tall, lower-level shaft and fourteen densely placed upper levels, topped by a parasol-finial (chattra) mounted on a lotus pedestal. The lower shaft has four large entrances open to the four cardinal directions, setting off eight other sides, each of which has a false-arch entry. All fourteen upper levels are similarly decorated with regularly placed false windows and doors. The entire pagoda reaches a height of 39.9 meters. Despite all of these details, this physically imposing structure serves no practical purpose. No facilities for climbing were built inside or outside, and none of the windows and doorways is truly functional other than the four entrances on the ground level.[5] The pagoda is essentially a hollow shell that has neither interior spaces nor actual levels.

One might argue that, though nonfunctional, the pagoda is significant in its symbolism, including that associated with its height. Many have proposed non-Chinese sources for the form and height of the pagoda at the Songyue Monastery, and its unusual dodecagonal structure may represent attempts by Chinese builders to construct a circular Indian stūpa.[6] Nonetheless, the pagoda’s curving profile, gracefully created by a diameter that decreases from the lower level upward, has no Indian counterpart. The style of tightly constructed eaves up to the finial is also a unique feature that is specific to Chinese pagodas throughout history. Called miyan 密簷 in Chinese, the closely piled eaves, though physically nonfunctional, appear to visually compress the building levels and consequently enhance or exaggerate the pagoda’s soaring verticality.[7] At stake in this compression and exaggeration of multiple building levels was height, one of the most important features of Chinese pagodas.

Built over a relic crypt, the pagoda at the Songyue Monastery is profusely symbolic. In an early eighth-century stele, the pagoda was extolled for its vertical dimension, dodecagonal shape, and building details, all religiously important for outwardly manifesting the relics enshrined inside.[8] The height of the pagoda, however, draws attention to more than its exterior and symbolism. In 1989, two crypts (fig. 2b) were found inside the chattra. The evidence from the crypts points to a mid-tenth-century date for their construction, about four hundred years after the pagoda was built.[9] What do we make of these two crypts, which builders or devotees went to the trouble to construct at the very top of the pagoda, invisible from the outside and inaccessible from below? In other words, by the tenth century, the pagoda was asserting itself vertically not just visually with its exterior but physically with its interior, although it was nothing but an airshaft.

I argue that the height of the multilevel pagoda is necessarily performative because it engages devotees in ways that other traditional Chinese architectures did not. Here, the term performative refers not to the pagoda actually acting or performing in motion but to its engagement with the visitor in ways that communicated its symbolic meanings and enacted its religious functions.[10] Early in China’s history, multilevel structures, including pagodas, were made possible by the available building technologies. Yet it was in the pursuit of height that pagodas became much more effective and active, not only because they visually enticed visitors but because they physically engaged practitioners through their interior spaces and multiple levels. This was particularly so during China’s Middle Period, when the greatest number of multilevel pagodas were constructed, with more elaborate relic depositories and iconographic programs than ever before.[11] New ritual practices and concepts of relics in relation to the pagoda were important factors in this history. I contend that the vertically oriented, multilevel pagoda was built with “agency,”[12] i.e., the pagoda interacted with and instructed the practitioner in the ritual efficacy it was built to fulfill. The term agency is used here to indicate the multilevel pagoda’s means of achieving height—through such features as its elevation, levels, and centralized structure—that concurrently affect the ways it interacts with visitors and reveals its religious significance.[13] The multilevel pagoda, in other words, did not just carry symbolism or ritual functions, but it performed them.

This study is not meant to be a comprehensive survey of all pagodas from the Middle Period; in fact, it draws many examples from the Liao (947–1125) territory in the north and northwest part of China, where one finds a great number of multilevel pagodas.[14] Instead, the goal is to locate the essential factors, both religious and nonreligious, from this period that made the multilevel pagoda a much more enticing and demanding architectural structure. Unlike the majority of the Liao pagodas, many multilevel pagodas built in China during this period had an accessible interior. To a significant degree, however, the ways in which the multilevel pagoda was conceptualized and the performative manner in which it engaged the user were consistent and comparable, regardless of its style, form, or function.

In this essay, I first investigate how height came to be an exceptional building quality and what it meant in the history of Chinese architecture until the Middle Period. I will then demonstrate how the multilevel pagoda, from the inside out, can be considered a “structured mechanism” that performs, acts, and interacts with visitors in the context of Buddhism and its ritual practice. It structurally activates the faithful’s vertical ascendance, prompts their movements from the periphery to the center, and unpacks the religious import of the iconography and relics that the pagoda enshrines. In this last sense, I will discuss the much-studied Timber Pagoda of Yingxian (1056). I propose that it should be regarded as a vertically oriented “performing center” in its engagement with visitors and transformation of onlookers into practitioners, while it transcends its physical structure to become a material manifestation of the Vairocana Buddha’s dharma body.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.