- Volume 45 | Permalink

Over the last decade, digital content and digitization projects have become increasingly prominent features of museum strategies, facilitating an ever-wider engagement with collections. This age of discovery has resulted from the throwing open of a digital window on museum collections and artworks that previously would have been either highly restricted or inaccessible. As this opening has grown in reach and sophistication, it has brought numerous benefits to museum education, research, cultural heritage, and tourism.

While digital access is broadly egalitarian in terms of extending access beyond a building’s physical confines, museums have had a variety of responses to making available their metadata. These responses are based on a range of factors, which may include the technical capabilities of collections management systems (CMS), variable cataloguing standards, limitations of funding or other resources, institutional capacity or priorities, and so on. Some museums have chosen to put all of their records online, while others have adopted more highlight-driven approaches. Equally, a variety of coexisting and complementary approaches to digital content are often the norm on museum websites, which feature innovative and ever-evolving ways of interacting and connecting with collections. These now include a proliferation of social media, virtual reality, apps, games, blogs, podcasts, and videos. All of these digital iterations are potentially more convenient to edit, supplement, and update than galleries or print catalogues (though whether they are as durable as their more traditional counterparts is questionable). In the digital sphere, the emphasis continues to be on engaging and educating museum audiences ranging from the popular to the academic.

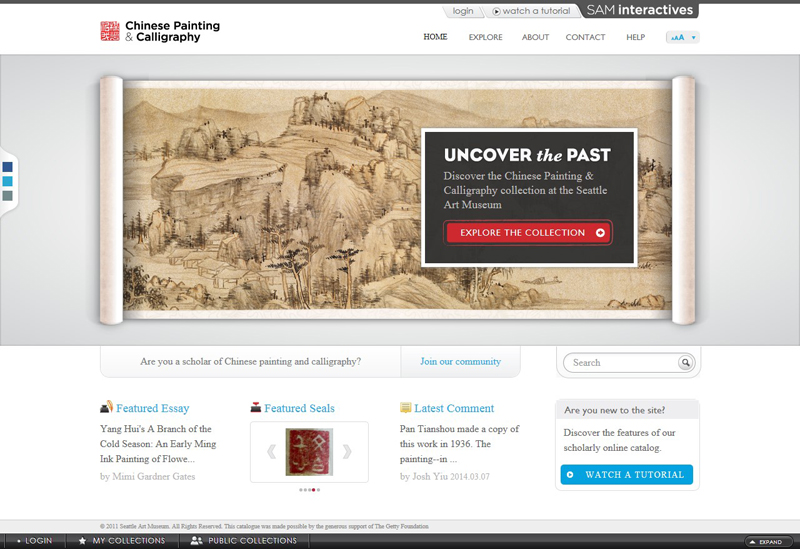

The Seattle Art Museum’s (SAM) Chinese Painting & Calligraphy online catalogue is the result of involvement with the Getty Foundation’s Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI). Launched in 2008, this consortium of nine institutions—Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Tate Gallery, London; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles—collaboratively explored how best to produce online scholarly catalogues of areas of their collections. SAM’s catalogue first went online in trial form in 2013 after five years of planning and preparation, suggesting that quality online catalogues demand at least as much commitment and investment as their analog counterparts.

The SAM collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy numbers 152 pieces, many never before published. Four categories separate the artworks in the catalogue. Group I features eighteen Song dynasty (960–1279) to modern or post-dynastic (1911–present) works, each with an in-depth essay by a leading art historian or curator. Group II features thirty-two mainly late imperial or modern works, each with a short essay by an advanced graduate student. Written by authors from Taiwan, China, and the United States, the essays and analyses accompanying the artworks in Groups I and II reflect the different academic traditions and backgrounds found in the field of Chinese art history. These distinctions have been preserved by the editors, who seem to have realized that the essays will be not only read by a much more diverse audience than that of a print catalogue but also understood and used in a new way. The essays are fully footnoted and illustrated, an aspect of the online catalogue that is especially noteworthy with so many leading scholars collaborating on the project.

Group III features sixty mainly late imperial to modern, newly acquired works awaiting further analysis and scholarship. Finally, in Group IV there are forty works that have either questionable or unknown attribution, or are simply considered of less interest. These groupings are readily identifiable under the Works of Art filter at left. Other filters conveniently sort the artworks by associated essayist, period, format, region, artist, or subject; the results can then be further ordered by artist, title, or date. Users also can search by keyword. (A valuable tutorial video in the Help section offers a tour of the online catalogue’s functionality.)

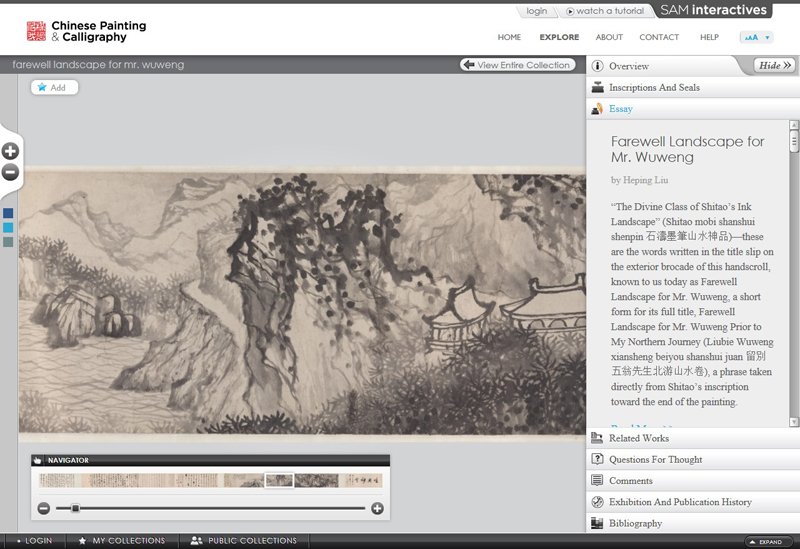

Chinese Painting & Calligraphy immediately impresses on many levels. It is readily apparent that the catalogue represents a very thoughtful and carefully produced online presentation of the collection, offering complementary—and elegantly implemented—methods to engage with the works. The high-resolution, zoomable photography is exemplary. Images of these paintings and calligraphies can be viewed in their entirety or studied with a level of clarity that reveals even the texture of the silk or paper. A separate Navigator window always identifies which area of an artwork is being studied. While this experience could never supplant viewing an artwork firsthand, it is hard to envisage how it might be improved upon. The online feature allows artworks to be viewed in greater detail (and with far greater convenience) than would be possible in a print catalogue or an exhibition. This is particularly so for handscrolls, which can be comfortably viewed in their entirety, something that otherwise might happen only in a limited number of real-world contexts.

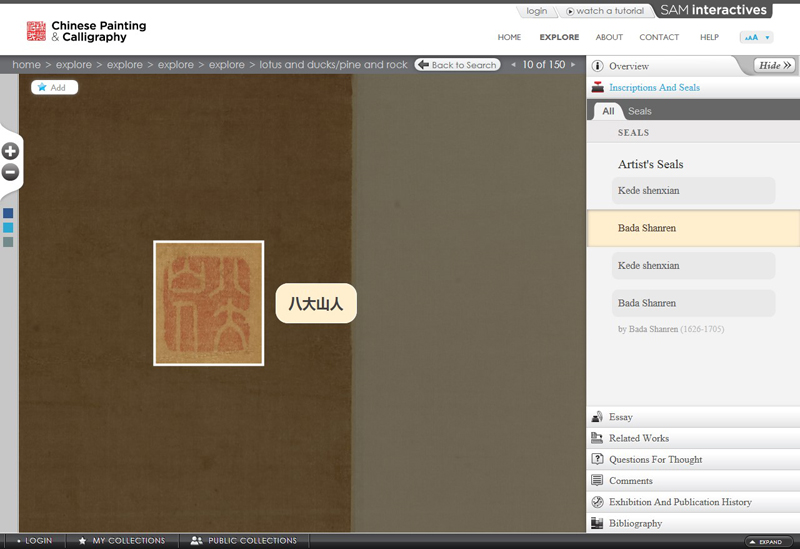

An excellent example is Shitao’s Farewell Landscape for Mr. Wuweng. Once the entry is opened, an image of the handscroll appears at center screen with a Navigator window in proximity. To the right, a sidebar panel offers a structured layering of related information, filed under categories including Overview, Quick Facts about the Artist, Inscriptions and Seals, Essay, Related Works, Questions for Thought, Comments, Exhibition and Publication History, and Bibliography. (The sidebar panel also can be minimized if the viewer simply wishes to engage with the artwork alone.) The execution of this supplemental material is outstanding, notably in the always-challenging area of Inscriptions and Seals. Clicking on the English translation of a colophon, inscription, or seal highlights the original in the artwork and brings up the Chinese transcription in a modern typeface. Names, terms, and titles also appear in Chinese, underlining the scholarly nature of the catalogue. The menu options are implemented most fully for the Group I and II artworks, and minimally for the Group IV artworks, which typically have only tombstone information.

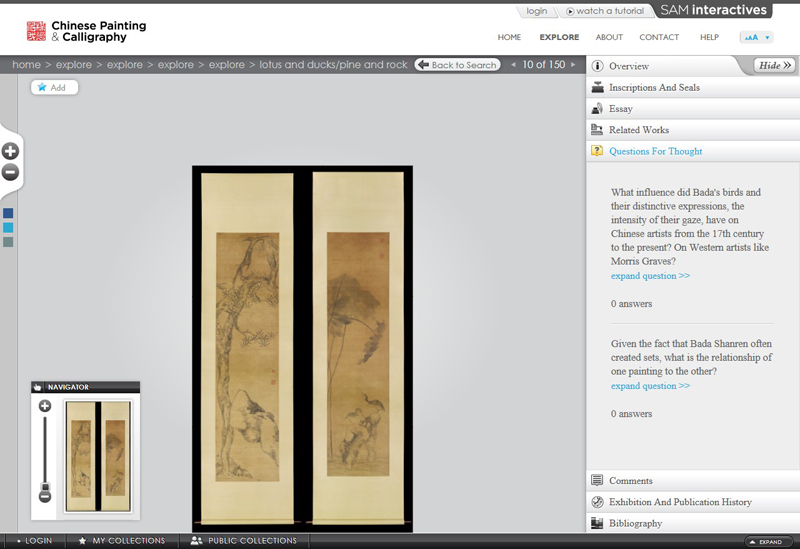

One of the great successes of Chinese Painting & Calligraphy is the admirable openness with which it engages both its complex material and the viewer. This is particularly striking in two areas: the presentation of the Group IV works and the Questions for Thought menu option. Both elicit curatorial perspectives by foregrounding issues and questions that curators frequently need to address, such as how to deal with artworks of questionable attribution. The inclusion of a relatively weak collection area in Group IV represents an innovative choice by SAM—one that is counter to conventional museum practice, which seeks to emphasize collections’ strengths. This is a bold and welcome decision, clearly made possible by the online nature of the catalogue, and in line with SAM’s intention to use the site as an open-ended portal to the collection, to which further acquisitions will be added as they are acquired.

Questions for Thought uses well-formulated questions to open up artworks to further discussion and intimate how they might be approached through curatorial or scholarly eyes. Viewers can register on the website to leave comments on individual artworks or essays, as well as to create personal annotated collections of artworks using the Add to My Collections button found on each catalogue entry. SAM also actively invites registered scholars to contribute to the Group III material; the museum will consider publishing each contribution and, if sufficiently well argued, reclassifying it into either Group I or Group II.

Chinese Painting & Calligraphy is a significant contribution to the study of Chinese painting and calligraphy in digital form. The interface never feels unwieldy or intrusive, and the facility with which one can navigate the artworks and related information makes using the catalogue a hugely rewarding and enjoyable experience. The SAM catalogue has correctly chosen to define itself with high-quality photography and good scholarship, and these twin approaches should ensure its longevity. At the very least, it must be considered a reference point for all future online catalogues of Chinese painting and calligraphy, if not the benchmark by which all such catalogues should be judged.

Ars Orientalis Volume 45

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.013

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.