- Volume 45 | Permalink

Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s online catalogue of Southeast Asian art was formally launched on November 20, 2013. It was the first in a series of web catalogues designed to bring the scholarly reading experience online via an open-access platform, in contrast to publications on subscription-only websites. The catalogue was made possible through the Getty Foundation-funded Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI), using the OSCI toolkit first developed at the Art Institute of Chicago. Other museum collaborators, many of which have subsequently launched their own sites/catalogues focusing on specific artists (Monet, Renoir, Rauschenberg) or art historical subjects (Japanese illustrated books, seventeenth-century Dutch painting, performance-based art), include the Freer|Sackler, National Gallery of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Seattle Art Museum, Tate Gallery, and Walker Art Center.

OSCI is an eminently commendable venture in helping people access, engage with, and develop a finer-grained knowledge of museum objects. The initiative and the sites it has produced embrace technology and correctly recognize the merits of widely disseminating information. Online features allow for more engagement than time- and geography-bound occasions such as special exhibitions and museum visits typically can afford. More specifically, LACMA’s site could be of immense value to scholars of Southeast Asian art who are without easy access to institutional publications or American museums. And although the digital cannot replace the materiality of the object or the role of encounter (nor is this the intention), the resources these sites offer are complements that can enhance the understanding of such works.

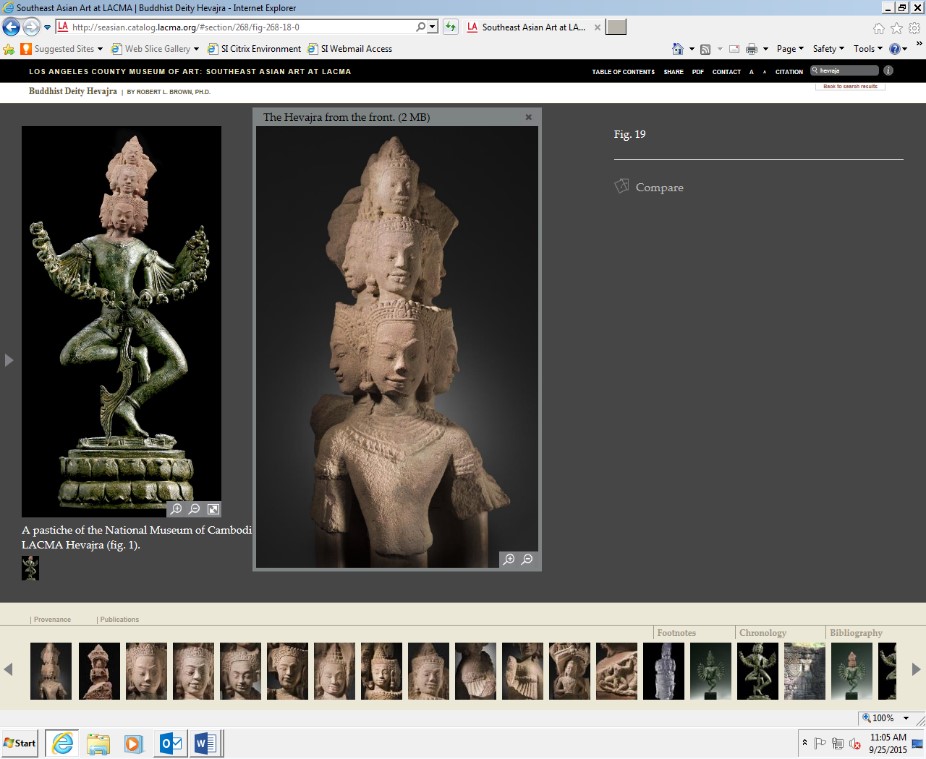

As a museum-based production, Southeast Asian Art at LACMA addresses a selection of Hindu and Buddhist Southeast Asian objects from LACMA’s collection through object-focused and thematic analytical essays. The principal author is curator Dr. Robert L. Brown; the technical essays were contributed by conservator John W. Hirx. Twenty catalogue entries spotlight single objects or groups of objects. In these close readings, Brown focuses on stylistic analysis and culturally contextual interpretations of the works, drawing upon extant scholarship and presenting cogent summaries of different arguments. Nevertheless, Brown’s authorial voice comes through. He carefully articulates the extent to which he agrees or disagrees with other authors, and he often offers fresh interpretations of familiar objects. Brown’s analysis of the Hevajra sculpture is a case in point, in which he compellingly challenges the reading that scholar Pratapaditya Pal posited in a preliminary study (1994–95). Yet in this and other entries, the spirit of engaging with and occasionally contesting existing studies seems to be underpinned by a desire to see the scholarly field expand. If some interpretations seem speculative, they nonetheless remain grounded in existing research; thus the analytical leaps that Brown makes seem convincing, not least because the many unknowns are also frankly acknowledged.

While recognizing that much remains inconclusive with regards to the art of Southeast Asia, the object entries show that carefully bringing together resources, textual and particularly visual, has created a tremendous resource for future research. The entries would have benefited, however, from the inclusion of the maps that are present alongside corresponding entries in the PDF format. For the most part, the choice of comparative images is excellent and extensive (from objects in European museums to photographs of sites in Southeast Asia), and they are of high quality. Occasionally, though, pertinent comparisons are missing. There is a conspicuous lack of comparative examples in the entry on the Sukhothai-Style Buddha, for instance. The entry on the couchant deer mentions that it is one of a group but does not illustrate any other examples.

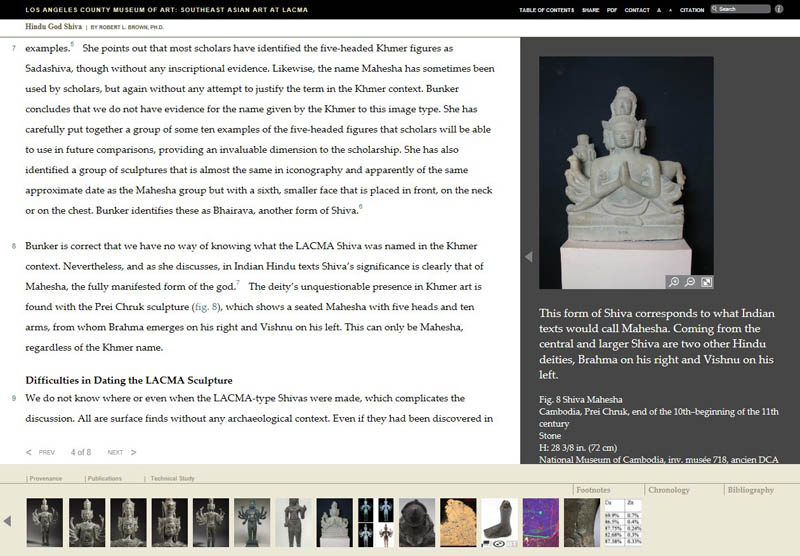

Still, Brown and the site’s developers have rightly recognized how visual play can help readers imagine contexts in which such objects could have existed. This is seen not only in the fascinating reconstructions of the Hevajra sculpture, whose head has been Photoshopped onto a bronze sculpture to suggest how it might have stood (or rather danced!) if complete, but also in the coloring-in of the robes of the tenth-century Cambodian sculpture of Vishnu.

The Vishnu object entry also exemplifies another unique and important aspect of the site—the inclusion of technical studies alongside art historical readings. Conservator Hirx opens up new dimensions to the perceptions of these objects. His use of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to confirm that the double vitarka mudra is present in Buddhist votive tablets, for example, imparts a better understanding of the art historical and scientific approach working in tandem. Insights on the repair of the Burmese wooden Buddha’s head and the separation of the Vishnu’s head from its torso prior to its rejoining at LACMA suggest successive uses (and abuses) of objects over time. Hirx’s technical examinations also led to the radical redating of a trio of Burmese wooden sculptures, revealing that one belongs to the Pagan period and is the only known example of its kind. Such discoveries are a good reminder to art historians of the limits of stylistic analysis alone and the advantages of collaborating across disciplines.

Woven through his essays, Brown makes note of other pitfalls in the study of Southeast Asian art. He acknowledges the limits to relying on texts, particularly South Asian sources, to interpret Southeast Asian art material. (He questions the actual pervasiveness of Sanskrit in Southeast Asia in his essay on the relationship between the two regions.) In the essay “Buddha with Attendants on a Winged Animal,” he notes, “Rather than searching (thus far unsuccessfully) for a narrative in which to embed the flying Buddha, we might think of the imagery used to indicate a place—that is, the sky—where the Buddha is performing a lecture.” Brown also addresses the issue in his essay brilliantly arguing that local implications produced the imagery of the Thai sculpture Monkey’s Gift of Honey to the Buddha. Indeed, a noteworthy approach—particularly given the fraught history of overusing South Asian lenses to interpret Southeast Asian art—is the emphasis on local cultures. In his entry on the Durga sculpture, for example, Brown compellingly highlights sacrifice in Java as a potential explanation for the buffalo’s nobility and the goddess’s pacific aspect.

Navigation and Organization Review

I loaded the catalogue on several browsers (Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, Safari, and Firefox) and accessed it on a Mac, a PC, and an iPad. (The site is not ideally viewed on an iPhone, and the developers have rightly suggested relying on a larger screen.) It works fairly consistently on all browsers; however, a few notable glitches occur. The catalogue has a very useful feature in which terms from its glossary (accessible through a separate link under the back matter) are highlighted in the text, and hovering over a term brings up its definition. This feature does not work when using Internet Explorer. And although the catalogue has a citation tool that provides a permanent link to the appropriate place in a paragraph, when using Google Chrome the text itself cannot be selected and hence cannot be copied or pasted elsewhere.

The site is well laid out and feels uncluttered, and navigating it is fairly intuitive. Entries are grouped in three clearly marked tabs (Catalogue Entries, Thematic Essays, and Backmatter) on a beige background, and the clickable signature images for each entry form a running strip at the base of the site. The entries themselves follow a clear, standardized format, with text on the left and images on the right. Besides the glossary and citation tools already mentioned, the site also has a figure viewer that allows readers to zoom, download, and compare the many high-quality images. Another noteworthy feature is the ability to download all or part of the catalogue as a PDF for offline viewing—particularly since the PDF includes elements missing from the main site, notably the maps. While it is extremely convenient to have the chronology and bibliography accessible through clickable tabs alongside the text, the site could have been enhanced by a consolidated bibliography and chronology or timeline in its back matter.

Aimed at an informed scholarly community, LACMA’s online scholarly catalogue of Southeast Asian art nevertheless contains elements that have a wider appeal. Scholars will find the object entries engaging, while the thematic essays and glossary can be instructional for students and useful in the classroom. “Catalogue” (in contrast to “archive” or “database”) is an apt term, as in form and structure the site resembles the scholarly publications intended to accompany exhibitions. The catalogue also has been appropriately linked to LACMA’s online Reading Room, where digitized versions of exhibition catalogues have been made available to view and download.

LACMA’s choice to focus on objects from its Southeast Asian Art collection is noteworthy and admirable. Not only is there a paucity of exhibitions focused on art from the area (particularly in comparison with East Asian and even South Asian art), but also there remains much to be discovered and understood on the subject. In making available high-quality texts and images to multiple audiences, the catalogue succeeds in its ambitions of being an important resource in the digital age.

Ars Orientalis Volume 45

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.012

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.