- Volume 45 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 513kb

Although largely focused on the premodern architecture of the Indian subcontinent, the essays in this issue of Ars Orientalis raise fundamental questions about the transmission of architectural knowledge and its reconstruction and representation in modern scholarship. As the authors all acknowledge, it is not enough to point to the synchronic or diachronic transmission of architectural forms, modes, and styles or even to address the pragmatics of transmission: we are also tasked with understanding the more obscure (at least to modern eyes) cognitive and/or cultural mechanisms that facilitated or impeded their circulation and use. These essays therefore engage questions of architectural citation, mediation, transmission, and translation that will resonate with those researching the architecture of times and places quite distant from the ones discussed here.

Focusing on Hindu and Jain temple architecture, the four articles discuss two distinct, if related, aspects of architectural transmission and the cognitive categories and empirical practices that underlie it. Crispin Branfoot and Julia Hegewald offer diachronic histories of specific forms and modes of architecture whose earliest histories were tightly circumscribed, regionally and temporally, but which went on to enjoy a transregional (and ultimately transnational) popularity as visual hallmarks of reified religious and regional identities. Branfoot analyzes a specific element of Tamil Drāvida architecture, the gopura, a monumental multi-tiered temple gateway found in Tamil Nadu’s Hindu and Jain temples from as early as the tenth or eleventh centuries, and its later canonization as the hallmark of South Indian temple architecture. Paradoxically, this process of canonization was achieved not only through the gopura’s eventual adoption in the architecture of Vijayanagara, an imperial formation centered far to the north of Tamil Nadu (where the form originated), but also through the collapse of the Vijayanagara polity in 1565. In its aftermath, subsequent local dynasts seeking to associate their rule with Vijayanagara facilitated the dissemination of this centuries-old element of the Drāvida architectural mode across South India. With the global dispersal of South Indian communities through colonial and postcolonial trade and other networks, the gopura was projected on a world stage as an index of a South Indian identity inflected by modern iterations of regional nationalism.

What is striking about the transformation of a specific element of Tamil Drāvida architecture into a global marker of regional identity is the constellation of agency and contingency, regional and transregional power, and modern economics and geopolitics that underlay it. A similar dynamic is apparent in Julia Hegewald’s case study, which considers the Māru-Gurjara architectural mode developed under the Solaṅki rulers of southern Rajasthan and Gujarat in the tenth to thirteenth century. This mode underwent a revival in its region of origin during the fifteenth century, after which it was adopted as a transhistorical, transregional, and, later, transnational style for many Jain communities in India and the diaspora. The limits of circulation and transmission are equally striking: within the subcontinent, the adoption of the Māru-Gurjara style outside of northwestern India is associated with Marwaris of the Śvetāmbara Jain community rather than the Digamabara Jains. Conversely, such divisions do not pertain as readily among diaspora communities, but even here there are differences between North America on the one hand and Europe and East Africa on the other.

Both essays raise larger questions about how and in what circumstances formal or ornamental features become signifiers of reified identities. Despite the element of contingency, certain constants are apparent in the canonization of both the gopura and the Māru-Gurjara mode as transregional and transtemporal signifiers of identity: They are associated with major political formations and revivalist impulses that invoke them as legitimizing precedents. They are products of migration, not simply of artisans but also of religious practitioners and community members with particular expectations regarding the appearance of a sacred space. In both cases, the canonization of a specific architectural form or mode was closely tied to the visual articulation of specific forms of identity; once established, this relationship between architecture and identity shaped the cognitive categories of subsequent patrons and practitioners. The phenomenon is by no means confined to specific Hindu or Jain communities: it finds a counterpart, for example, in the emphatic role of domes and arches within the earliest mosques and tombs built for Muslim communities throughout the subcontinent. These often were constructed by adapting techniques of corbelling or even by carving massive monolithic stones to (re)produce arcuate forms evidently considered desiderata by Muslim patrons.[1]

Questions about the agency, expectations, and habitus of consumers, patrons, and viewers are equally relevant to the case studies presented by Nachiket Chanchani and Tamara Sears, which offer empirical approaches to the question of how architectural forms and ideas traveled in premodern South Asia. Both focus on a slightly earlier period of North Indian temple architecture, between the ninth and eleventh centuries, to engage significant questions about the pragmatics of formal or stylistic mobility and transmission. Both demonstrate the value of close looking as a way to compensate for a paucity of contemporary epigraphic or textual evidence that will be familiar to many medievalists.

Sears considers the temples constructed in Kadwāhā in central India between the ninth and eleventh centuries. Kadawāhā was not a royal center but was well situated at the nexus of interstitial routes. The site offers a glimpse of patronage characterized not by a top-down model but one that reflected the needs and desires of the religious communities served by its temples. This devolved structure of agency, Sears argues, is most visible in the treatment of the ornamental forms that covered temple exteriors, which reflect the choices made by local artisans rather than architects or patrons alone. Paradoxically, perhaps, the retooling of existing figural imagery on stones reused in the construction of early Indian mosques indicates a comparable scenario: while there appears to have been a general order to deface, wide variations in the specific manner of defacement suggest that masons had some leeway in their implementation of that order.[2] Such transformations represent a very literal instance of a general principle that Sears sees at work in the temples of Kadwāhā, noting that formal change can be driven not only by aesthetic but also by religious concerns. Indeed, when it comes to the construction of sacred space, the two often coincided.

If the site of Kadwāhā highlights questions of transmission over regions of physical contiguity, the pilgrimage site of Pandukeshwar in the Central Himalayas, discussed by Chanchani, highlights a dramatic instance of architectural displacement. The site preserves a remarkable juxtaposition of ninth- or tenth-century temples built in the Nāgara mode favored in North India with those built in the Drāvida mode usually found in regions that lay far to the south. The appearance of Drāvida modes of temple architecture in the far north raises profound questions about architectural mobility, about how and why specific modes of architecture travel over extraordinary distances. That Drāvida-style temples appear far from their region of origin is not in doubt: they have been documented outside of India, as far east as Quanzhou in China.[3]

Without engaging the thorny issue of how we define style, it is important to recognize that our ability to recognize such displacements, as indexes of circulation and transmission, depends on the operation of style as a formal category with a circumscribed geographical range. This entails the privileging of form, a visual index of mode or style, over facture, which is generally less susceptible of visual analysis alone. The consistency and seriality produced by the repetition of specific forms or ornamental modes outline, however schematically, the boundaries of architectural modes or styles and their circulatory parameters. The essays by Branfoot, Hegewald, and Sears suggest that the replication of specific forms or modes can align the architecture of a particular locale with broader or earlier antecedents, suggesting continuities even where none exist, through reuse or revival, for example.

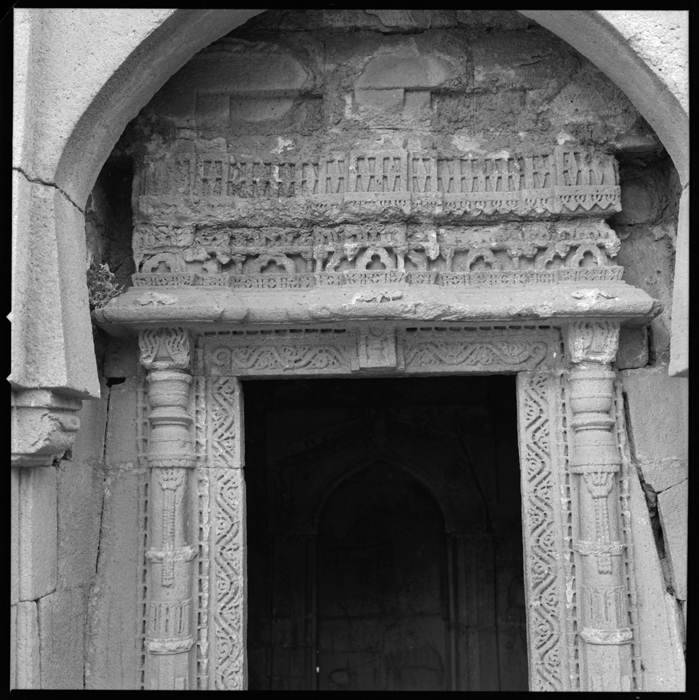

Reuse reminds us that just as ideas about architecture move, so do monuments and their elements. If, as Branfoot demonstrates, sthāpatis (master artisans) from the Tamil South working at the Deccani imperial capital of Vijayanagara in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries facilitated the mobility of the gopura form, it is also worth noting that the Vijayanagara rajas relocated major monuments of the earlier Chalukya dynasty to their capital (fig. 1). The allure of these architectural antecedents was also sufficiently powerful to ensure the persistence of Chalukya elements in the architecture of the Bahmanid sultans of the Deccan (1347–1527), either as reused fragments or as newly carved stone elements executed in the basalt and dolorite favored in Chalukya architecture and often executed according to Chalukya conventions. Bahmanid formal and ornamental elements were, in their turn, considered worthy of emulation in Vijayanagara, completing a circle of Deccani self-referentiality that required different kinds of architectural transmission across time, from conceptual and practical to literal and synecdochic.[4]

Hegewald describes the repetition and perpetuation of Māru-Gurjara forms as a citation of Solaṅki style. It is important, however, to distinguish between different registers of association created through replication. One might imagine the transmission and replication of specific formal or ornamental features as locating a monument anywhere on a continuum from participation in a tradition reified by the survival of antecedent monuments to the more pointed case of citation. Citation entails the replication of resonant architectural or ornamental forms whose characteristic features evoke those of specific prototypes; in the Islamic world, common prototypes included the Sasanian palace at Ctesiphon (4th–6th century CE) and the Friday (or Great) Mosque of Damascus (715 CE), built by the Umayyads, the first Islamic dynasty, and considered one of the wonders of the medieval Islamic world.[5]

Knowledge of such prototypes was acquired either from firsthand experience or from textual and/or verbal descriptions.[6] In the case of the Friday Mosque of Damascus, for example, the distinctive triple-aisled prayer hall inspired the form of a series of Friday mosques in the surrounding cities of Syria and the Jazira for centuries after the fall of the Umayyad dynasty. However, this diachronic participation in a regional tradition also existed alongside more specific synchronic references to Damascus in mosques built outside of the region, which sought to appropriate some of its fabled aura or to forge fictive continuities by replicating one or more of its characteristic features.[7]

As this suggests, the association of characteristic architectural forms or ornamental modes with site-specific archetypes often encouraged their mobility; their appearance in later structures was intended to evoke prestigious antecedents. Conversely, sometimes inscriptions or texts indicate a relationship to valorized prototypes that are not readily apparent in the formal qualities of the monument, at least to modern eyes. As late as 1440, for example, the foundation inscription of the Friday Mosque of Mandu in Malwa describes the mosque as a copy (nuskha) of the Friday Mosque of Damascus, although it is difficult to see any close formal relationship between the two.[8]

Examples of what Terry Allen has dubbed “style out of place” provide insights into the cognitive capacities of premodern builders, patrons, and viewers as well as their ability to recognize the regional filiations of style and, on occasion, to exploit formal or stylistic difference for various ends.[9] In cases like Pandukeshwar, in which we appear to be dealing not with the diachronic dissemination or reception of architectural modes in contiguous regions, but with a synchronic intrusion, the stakes are high in determining the meaning(s) of both alterity and mobility. In his analysis, Chanchani moves from the micro-level of analyzing facture and form to the macro-level of positing the juxtaposition of distinct regional modes of architecture as evidence for the early emergence of “an evolving idea of India,” the visualization of a transregional cultural or geographic imaginary. The move is a bold one. It engages a long-running controversy between those who deny that any idea of India as a culturally cohesive entity existed before the colonial period and those who assert a contrary position by no means confined to traditional nationalist histories. The argument entails a paradox worth noting: if, as Chanchani suggests, the juxtaposition of distinct regional modes of architecture in the pilgrimage sites of the Himalayas reflects an emerging transregional imaginary, a polyglot visuality that “could transcend the confusion of tongues,” then the very capacity for transcendence is rooted in an ability to recognize difference within architectural languages with specific regional associations.

In the Islamic world, the displacement of regionally specific architectural forms and modes across space and time often was associated with the movement of artisans and patrons. Examples include the mosque that the rebellious Abbasid governor of Egypt, Ahmad Ibn Tulun, built near Fustat in 879, a mosque that appropriated forms and modes of construction that were foreign to Egypt but had been recently developed in the Abbasid capital of Samarra in Iraq. These included brick piers, a spiral minaret on an axis, and modes of Iraqi stucco ornament (figs. 2, 3). While it is easy to imagine the transmission of the mosque’s formal features through firsthand experience and verbal description (Ibn Tulun had been raised in Samarra), the appearance of Abbasid-style stuccoes may indicate the presence of Iraqi artisans in Egypt.[10] Similarly, the appearance of Persianate forms of decoration, including glazed tiles, in Cairene architecture of the early fourteenth century seems to reflect the presence of artisans from Tabriz in Iran.[11]

In other cases, claims of cosmopolitanism or transregional sovereignty were asserted by the juxtaposition of different modes or styles, or by the novelty associated with the construction of “out of place” monuments in ways that subverted (while exploiting) the coincidence between cultural and physical geography. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, for example, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed erected three pavilions on the grounds of Topkapı Palace, each in a different style—Turkish, Persian, and Byzantine-Greek—as a sign of his dominion over each of these realms (fig. 4).[12]

The staging of difference in such assertions of sovereignty may be relevant to the surprising appearance of the Māru-Gurjara mode discussed by Hegewald in relation to Jain architecture well to the east and west of its Gujarati homeland. The existence of Māru-Gurjara-style Hindu temples in the Central Himalayas, 1,500 kilometers from Gujarat, and even up to the border of Nepal, has been documented, for example, by Nachiket Chanchani.[13] Perhaps more surprisingly, the westernmost extension of Māru-Gurjara architecture takes the form not of a temple, but a small stone mosque or tomb built at Larvand in the remote mountains of central Afghanistan around 1200. This was provided with an applied façade that represented an adaptive reworking of the contemporary Māru-Gurjara vocabulary (fig. 5). As its name suggests, the Masjid-i Sangi (Stone Mosque) was built in stone rather than the more usual brick, reminding us that materials matter, as do the choices that underlie them, whether the choice was to build in stone rather than wood in the Central Himalayan temples (discussed by Chanchani) or to clad the modern Jain temples with white marble and red sandstone characteristic of medieval prototypes in Gujarat and Rasjasthan (discussed by Hegewald). The Masjid-i Sangi was likely the work of Gujarati (possibly Jain) stone masons working for Muslim patrons whose tastes were informed by the contemporary Indian conquests of the Ghurid sultans of Afghanistan. In Gujarat itself, there are earlier precedents for the adaptive use of Māru-Gurjara forms in the construction of mosques and shrines.[14] Both these Gujarati monuments built for Muslim patrons and the appearance of Māru Gurjara forms as far west as Afghanistan remind us that the appeal of the South Asian architectural modes discussed in this volume was sometimes sufficiently potent to facilitate their transmission across sectarian boundaries that have often been exaggerated in representation.

In all of these cases, the transmission of architectural knowledge and the processes of adaptation, mediation, and replication that it entailed raises a methodological question of fundamental importance to those who work on premodern cultural production even outside of South Asia; in the absence of contemporary inscriptions, texts, or accompanying metadata that might shed light on processes of transmission and reception, how might one engage the archival potential of the monument itself? The essays by Chanchani and Sears are exemplary in this respect, demonstrating the value of close empirical and formal analysis underwritten by the comparative method that (explicitly or not) is the default mode of most art historical writing. Whether materials, plans, or the minutiae of sculpted ornament and religious iconography, close attention to detail enables one to reconstruct or recover aspects of the pragmatics of construction, some of the underlying choices that provide insights into the transmission and implementation of architectural knowledge.

Attempts to reconstruct the transmission of architectural knowledge between eastern Iran and northern India—which shaped the forms of the first North Indian mosques built around 1200—have identified points of commensuration between the pragmatics of architectural construction in the medieval Islamic world and in South Asia, at least insofar as they can be reconstructed.[15] The South Asian context is perhaps advantaged by the existence and survival of numerous śāstras, architectural treatises that predate the production of similar texts in the Islamic world, but their role in the practical process of architectural transmission is unclear. As Chanchani and Hegewald note, the lack of specificity regarding nuances of form and ornamental articulation in these often esoteric texts suggests the limits of textual mediation as a vector for the finer details of architecture; the limitation of textual descriptions has also been noted in relation to the transmission of complex ornamental forms in the medieval Islamic world.[16]

One further point of commensuration between what we know about the transmission of architectural knowledge in medieval South Asia and the Islamic world is the striking paucity of evidence for the use of graphic notation (plans, sections, elevations). Cartoons were used in the production of complex textile patterns in the late antique eastern Mediterranean, and at least one twelfth-century Byzantine manuscript shows Arab geometers transmitting their knowledge by means of drawings.[17] Despite this, in both the Islamic world and South Asia there is remarkably little evidence for the consistent use of graphic notation in the transmission or implementation of architectural knowledge before the thirteenth century or even later.

There are occasional reports of patrons sketching the desired form of a building on parchment or paper before construction; if these are trustworthy, they seem to have been the exception rather than the rule and may reflect the status of the buildings in question as elite building projects. When it came to more mundane or quotidian building practices, plans were not a desideratum; instead, in many regions of the medieval and early modern Islamic world, architecture entailed “design without representation,” a heuristic and integrated approach to construction and planning.[18] A tenth-century text from Bust in Afghanistan uses an extended metaphor of architectural construction to explain the agency underlying the Creation; it begins not with the drafting of any plan, but with the production of bricks for the walls and digging of foundations.[19] Generally, plans consisted of foundation lines marked on the ground with lime, ropes or—as indicated by reports of some unique city foundations, such as that of Baghdad (762 CE)—with more dramatic means, such as lines of flaming naphtha. Well into the twentieth century, Iranian builders used lime and gypsum to mark the outlines of the plan directly on the earth according to a pattern agreed by patron and builder; this was then excavated to create a foundation trench.[20] Planning and building were thus integrated; indeed, in the European context, it has been argued that the disaggregation of these embodied and imbricated practices in the fifteenth century was one of the defining hallmarks of an emergent modernity.[21]

If mental imagery, verbal communication, and embodied knowledge were more important to the process of formal transmission than graphic or textual mediation when it came to complex surface ornament, there is some evidence that preparatory drawing played a role. The narrow bands of Qur’anic text inscribed on the surface of the celebrated minaret of Jam in central Afghanistan (1174) not only describe a series of complex geometric patterns (fig. 6), but are arranged so that a key phrase falls exactly at the nexus of these patterns, a feat difficult to imagine in the absence of any preplanning or drafting.[22] Ethnographic evidence from twentieth-century Iran indicates that stucco workers and stone masons tasked with carving or molding complex relief patterns first traced the outlines of the desired ornament on the surface of the medium before commencing work.[23] However, apart from rough working sketches made on-site to calculate the trickier parts of the ornament or superstructure, such as stalactite muqarnas vaults, elevations seem to have been rarely used.[24] This is true even from the Timurid period (fourteenth to fifteenth century), when graphic notation or drawings (ṭarḥ) are more frequently documented, partly the result of the easy availability of paper.[25]

In South Asia, insights into the likely modes of transmitting Timurid forms (as well as their limits) are provided by the madrasa of Mahmud Gawan in Bidar (1472), the capital of the Bahmanid sultans of the Deccan (fig. 7). In its plan and polychromatic tile ornament, the madrasa represents a unique intrusion of Persianate style into the Deccan. Its plan replicates that of Timurid contemporaries such as the Ghiyathiya madrasa at Khargird in Khurasan (1442), perhaps reflecting the contemporary use of gridded paper, which promoted a certain modular or standardized plan.[26] However, the elevation of the building manifests a number of peculiarities with respect to such hypothetical models, including some very awkward attempts to create muqarnas moldings and vaults, which were evidently unfamiliar to those whose tentative efforts are preserved in the deepest, least visible, recesses of the corner rooms (fig. 8).

Discrepancies between the Bidar madrasa and the assumed Timurid model are similar to those seen in the temples of Pandukeshwar, which deviate from the norms of the Drāvida mode in their conceptual, formal, and aesthetic qualities. Both suggest the limits of models of transmission based on graphic notation or the migration of specialist practitioners alone. In thinking about modes of mediation that lie between the two, we might consider Chanchani’s interesting suggestion that master masons (sūtradhāras), who were quite locally rooted, may have been inspired not by purpose-built drawings or models (for which the evidence is negligible) but by such things as miniature shrines carried over long distances by pilgrims. Similarly, Sears considers the role of portable artifacts and media in the transmission of ornamental forms. The suggested intersection between agency and contingency in fostering new architectural possibilities is worth taking seriously. It resonates with recent suggestions that depictions of buildings on ceramics and other portable media, including objects in the form of microarchitecture, may have circulated ideas about architecture in medieval Anatolia and the Jazira, shaping the expectations and tastes of patrons and viewers.[27]

In both South Asia and the medieval Islamic world, the transmission of architectural knowledge reflected intersections and negotiations between local and translocal networks that first and foremost reflected the movement of human populations, whether as patrons, pilgrims, or practitioners. Even after the adoption of certain modes of graphic notation, architectural knowledge tended to travel “in the bodies of its practitioners” as Crispin Branfoot puts it. The mobility of artisans, builders, craftsmen and stone masons may not have been uniform or stable across regions and times; consider, for example, the relative frequency of references to Anatolian or Iranian architects in Delhi under the rule of the Tughluq sultans during the first decades of the fourteenth century.[28] In addition to the availability of patronage (or, conversely, the role of economic or political instability) in fostering mobility, those possessed of specialized skills may have been especially peripatetic, moving in search of employment that was not always available in one region.[29]

As the essays in this volume emphasize, in thinking about practicalities of transmission, it is vital to consider the routes along which artifacts, artisans, and ideas traveled, routes that were sometimes coincident with those walked by religious practitioners and pilgrims, what Chanchani refers to as “transregional knowledge corridor[s].” In the Islamic world, the role of the hajj in disseminating architectural forms experienced by pilgrims in Mecca and Medina—both of which were often embellished with the most current architectural forms and technologies—has yet to attract sustained study.[30] The role of nonspecialist experience and desire in facilitating the movement of architectural forms highlights a further dimension, which is noted but not explicitly considered in the essays included here: the role of memory and mental imagery in processes of architectural transmission. [31] This includes both forms of cultural memory that perpetuate specific styles across space and time, shaping the desires and expectations of patrons or communities of users, and the embodied memory that enables architects and artisans to reproduce forms and idioms capable of satisfying those expectations.

One final point concerns the transmission of architectural knowledge in the present, the representation of histories of transmission in modern scholarship. The richness of the emic architectural vocabulary that exists for medieval South Asia architecture and its elements is remarkable. The desire for fidelity to that emic tradition in much modern scholarship is admirable. Nevertheless, the act of representing medieval architecture is necessarily an etic gesture: we write for our peers, for whom the very richness and specificity of an emic architectural vocabulary can create barriers to accessibility, producing as arcane knowledge that would otherwise have much to offer those working in other fields of architectural history.

Notes

Finbarr B. Flood, Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval 'Hindu-Muslim' Encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 48. Perhaps the most remarkable example is the dome in the shrine of ‘Alā al-Dīn in Madura (fourteenth century or later), which measures almost six meters in diameter but is hollowed from a single stone block: Mehrdad Shokoohy, Muslim Architecture of South India: The Sultanate of Ma‘bar and the Traditions of the Maritime Settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Goa) (Routledge: London and New York, 2003), 39–42.

Risha Lee, “Rethinking Community: The Indic Carvings of Quanzhou,” in Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southest Asia, ed. Hermann Kulke et al. (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009), 240–70.

Richard M. Eaton and Phillip B. Wagoner, Power, Memory, Architecture: Contested Sites on India’s Deccan Plateau, 1300–1600 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014), 77–124. Helen Philon, “Architectural Decoration,” in Silent Splendour: Palaces of the Deccan 14th–19th Centuries, ed. Helen Philon (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2010), 114–21.

Bernard O’Kane, “Monumentality in Mamluk and Mongol Art and Architecture,” Art History 19, no. 4 (1996), 499–522.

Another potential source of mediation are the schematic drawings of extant and even long-vanished monuments included in the works of medieval geographers and travelers. That such graphic imagery has never been the subject of serious study is largely due to the practice of omitting drawings found in medieval manuscripts from published recensions of the texts in which they appeared. For a rare exception see Abu Hamid al-Gharnati, Al-Mu‘rib ‘an ba‘ḍ ‘aŷā’ib al-Magrib (Elogio de Algunas Maravillas del Magrib), ed. Ingrid Bejarano (Madrid: Fuentes Arábico-Hispanas, 1991).

Jonathan M. Bloom, “On the Transmission of Designs in Early Islamic Architecture,” Muqarnas 10 (1993), 24–26; Finbarr B. Flood, “Umayyad survivals and Mamluk revivals: Qalawunid architecture and the Great Mosque of Damascus,” Muqarnas 14 (1997), 57–79.

I am currently working on this inscription in the context of a larger study of architectural mimesis in the Islamic world.

Terry Allen, Five Essays on Islamic Art (Manchester, MI: Solipsist Press, 1988), 108. See also Lorenz Korn, “Iranian Style ‘Out of Place’? Some Egyptian and Syrian Stuccos of the 5th–6th/11th–12th Centuries,” Annales Islamologiques 37 (2003), 237–60; Flood, Objects of Translation, 189–218.

Bloom, “On the Transmission of Designs,” 22–23; Mat Immerzeel, “'Playing with Light and Shadow: The Stuccoes of Deir al-Surian and Their Historical Context,” Eastern Christian Art 5 (2008), 59–74.

Michael Meinecke, “Die mamlukischen Fayencemosaikdekorationen: Eine Werkstätte aus Tabrīz in Kairo (1330–1350),” Kunst des Orients 11 (1976), 85–144.

Gülru Necipoğlu, Architecture, Ceremonial and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991), 201-17; Scott Redford, “Byzantium and the Islamic World, 1261–1557,” in Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), ed. Helen C. Evans (London and New York: Yale University Press, 2004), 396.

Nachiket Chanchani, “From Asoda to Almora, The Roads Less Taken: Māru-Gurjara Architecture in the Central Himalayas, ” Arts Asiatiques 69 (2014), 3–16.

Max Klimburg, “Short preliminary report on our expedition to the Ghorat in October 1958, ” Afghanistan 14, no. 4 (1958), 16–19; Max Klimburg, “Blick auf Ghor, ” Du, Kulturelle Monattschrift 20 (1960), 40–50;Gianroberto Scarcia and Maurizio Taddei, “The Masğid-i sangī of Larvand,” East and West, n.s., 23 (1973), 89–108; Warwick Ball, “Some notes on the Masjid-i Sangi at Larwand in Central Afghanistan,” South Asian Studies 6 (1990), 105–10; Finbarr B. Flood, “Masons and Mobility: Indic Elements in Twelfth-century Afghan Stone-carving,” in Fifty Years of Research in the Heart of Eurasia, ed. Anna Filigenzi and Roberta Giunta (Rome: Istituto Italiano per l’Africa et l’Oriente, 2009), 137–60; Flood, Objects of Translation, 203–18. For the use of Māru-Gurjara forms in the Islamic architecture of Gujarat, see Alka Patel, Building Communities in Gujarat: Architecture and Society During the Twelfth Through Fourteenth Centuries (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2004).

Bloom, “On the Transmission of Designs.” See also Chanchani, “From Asoda to Almora,” 9–10.

Annemarie Stauffer, Antike Musterblätter. Wirkkartons dus dem spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Ägypten (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2008); Vasiliki Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle of Ioannes Skylitzes in Madrid (Leiden: Alexandros Press, 2002), 117–18, fig. 182.

Nasser Rabbat, “Design without Representation in Medieval Egypt,” Muqarnas 25 (2008), 147–54; Nasser Rabbat, “The Dome of the Rock Revisited: Some Remarks on al-Wasiti’s Account,” Muqarnas 10 (1993), 69. For a survey of the evidence, see Gülrü Necipoğlu, The Topkapı Scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture (Los Angeles: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1995), 3–28.

Oleg Grabar and Renata Holod, “A Tenth-Century Source for Architecture,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 3/4 (1979–80), 313–16.

Hans E. Wulff, The Traditional Crafts of Persia: Their Development, Technology, and Influence on Eastern and Western Civilizations (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966), 108.

Marvin Trachtenberg, Building in Time from Giotto to Alberti and Modern Oblivion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

As early as the 720s, test patterns for complex geometric designs were sketched on some of the stones of the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar: R. W. Hamilton, Khirbat al-Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), pl. V. Our earliest surviving examples of architectural design sketches are two-dimensional sketches for modules of a muqarnas found in Armenia and Iranian Azerbaijan: Ulrich Harb, Ilkhanidische Stalaktitengewölbe: Beiträge zu Entwurf und Bautechnik (Reimer: Berlin, 1978); Armen Ghazarian and Robert Ousterhout, “A Muqarnas Drawing from Thirteenth-century Armenia and the Use of Architectural Drawings During the Middle Ages,” Muqarnas 18 (2001), 141–54; See also Ömür Bakirer, “The Story of Three Graffiti,” Muqarnas 16 (1999), 61–62.

Necipoğlu, Topkapı Scroll; Jonathan Bloom, Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2001); Jonathan Bloom, “Paper: The Transformative Medium in Ilkhanid Art,” in Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, ed. Linda Komaroff (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 289–302.

E. Schotten Merklinger, “The Madrasa of Maḥmūd Gāwān in Bīdar,” Kunst des Orients 11 (1977), 145–57. On the role of gridded paper, see Renata Holod, “Text, Plan and Building: On the Transmission of Architectural Knowledge,” in Theories and Principles of Design in the Architecture of Islamic Societies, ed. Margaret Bentley Sevcenko (Cambridge, MA: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1988), 1–13; Jonathan M. Bloom, “Lost in Translation: Gridded Plans and Maps Along the Silk Road,” in The Journey of Maps and Images on the Silk Road, ed. Philippe Forêt and Andreas Kaplony (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 83–96.

Scott Redford, “Portable Palaces: On the Circulation of Objects and Ideas about Architecture in Medieval Anatolia and Mesopotamia,” Medieval Encounters 18 (2013), 84–114. See also the recent collection of essays edited by Patricia Blessing in Transkulturelle Perspektiven 3 (2014).

Mehrdad Shokoohy and Natalie H. Shokoohy, Tughluqabad: A Paradigm for Indo-Islamic Urban Planning and its Architectural Components (London: Araxus Books, 2007), 24.

A case in point is the expertise to construct complex geometric wooden ceilings: James Allan, “The transmission of decorated ceilings in the early Islamic world,” in Learning, Language and Invention: Essays presented to Francis Maddison, ed. W. D. Hackmann and A. J. Turner (Variorum: Aldershot, 1994), 1–31.

But see Jonathan M. Bloom, “The Introduction of the Muqarnas into Egypt,” Muqarnas 5 (1998), 21–28.

For an analogous case study, see Heather E. Grossman, “On Memory, Transmission and the Practice of Building in the Crusader Mediterranean,” in Mechanisms of Exchange: Transmission in Medieval Art and Architecture of the Mediterranean, ca. 1000–1500, ed. Heather E. Grossman and Alicia Walker (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 481–517.

Ars Orientalis Volume 45

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.007

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.