- Volume 45 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.3mb

Style and Architecture under the Solaṅkī Rulers

Northwestern India has a long and intimate connection with the Jaina faith. According to Jaina history, the religion reached the western region of India already during the lifetime of Mahāvīra, the historic twenty-fourth Tīrthaṅkara or Jina who lived in about the sixth century BCE.[5] Despite a number of Islamic incursions,[6] Jainism and its temple structures continued to flourish during the eleventh to the thirteenth century, when the area was under the control of the influential Solaṅkī or Cāḷukya/Caulukya rulers.[7] The Solaṅkī or Māru-Gurjara style of architecture started as a regional form but soon acquired supra-regional dimensions. Due to its opulent decorative features, the style is easily recognisable and even if only a few of its essential elements have been reproduced, it triggers an immediate recognition.

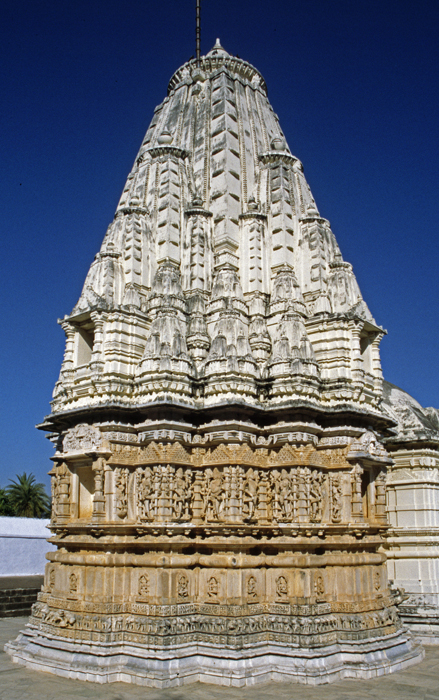

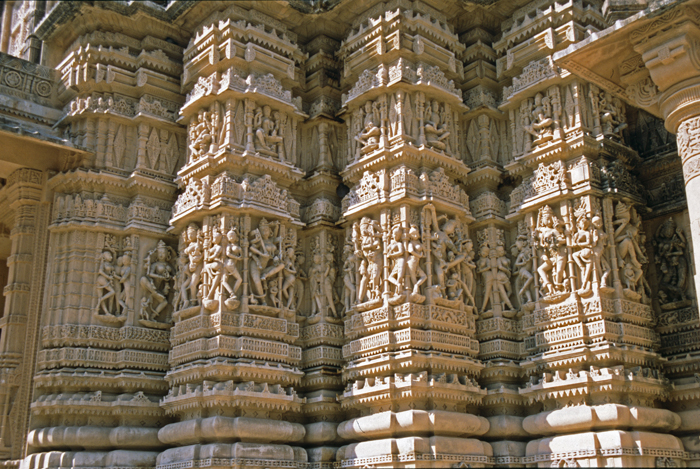

The Māru-Gurjara style is part of the northern Indian temple idiom, following the Nāgara design, in which the temple tower (śikhara) has a curvilinear shape (fig. 1). Both Hindu and Jaina temples were created following this style. Amongst its distinct features are that the external walls of the temples have been structured by increasing numbers of projections and recesses, accommodating sharply carved statues in niches. These are normally positioned in superimposed registers, above the lower bands of moldings (fig. 2). The latter display continuous lines of horse riders, elephants, and kīrttimukhas.[8] Hardly any segment of the surface is left unadorned.

Visually even more pronounced is the interior design of temples raised under Solaṅkī patronage. Typically, these have large, open pillared halls, which are lavishly ornamented. On the plan, the pillars are arranged in an octagonal shape and are carved from top to bottom with profuse decorations. These include floral and vegetal ornamentation, geometric design patterns, and many figural representations. Carved sculptures are finely cut and often heavily decorated. Sculpted figures adorn brackets projecting from the upper section of the pillars. Frequently, ornamental arches displaying a multi-cusped design have been thrown across the pillars forming the central octagonal area. These are known as aṇḍolā and resemble the design of a toraṇa (an ornamental gateway). The same kind of flying arches have also regularly been positioned between pillars framing the entrance or the sides of porches. Through this, a predominantly interior feature become part of the external appearance of temples. Besides, the ceiling panels of halls and ambulatories in this style have been lavishly decorated. Particularly famous are the domical ceilings formed out of diminishing concentric rings, following a trabeate (corbelled) construction technique.[9] From the center of the ceiling usually projects a large carved stone lotus pendant (padma-śila).[10] Some domical ceilings have multiple stalactite-like lotus projections. Jaina examples of such elaborate ceilings often display figural representations of the goddesses of learning and knowledge (vidyā-devīs).[11]

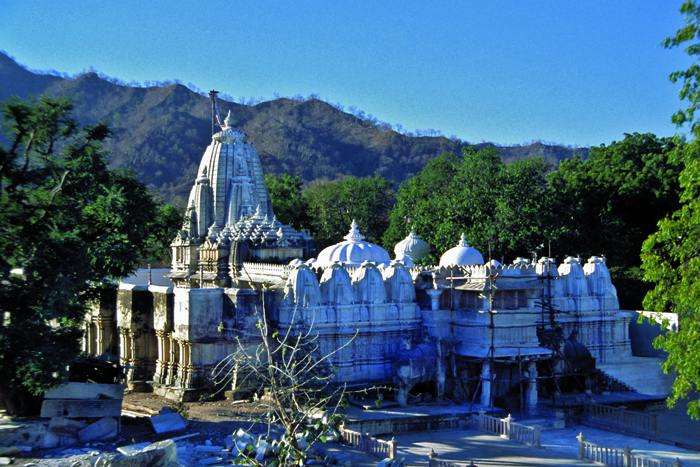

Although the decorative features of this medieval western Indian style are especially pronounced and representative and have consequently been copied most consistently, there are additional structural features, which typify the temples raised under the patronage of the Solaṅkī kings. The elements discussed above—profusely carved pillars, ceilings and flying arches—are particularly visible in the large, open pillared halls, which gained a specific prominence in complex Māru-Gurjara temples. Many Jaina temples have one closed and two pillared halls, further elongating the axis of approach to the principal shrine (fig. 3). Of these halls, the one closest to the compound entrance is in most instances raised on a slightly lower terrace than the more sacred building elements of the temples. These halls, which are designed to accommodate dance and dramatic performances as well as communal worship, are referred to as raṅga-maṇḍapas and are considered to be a Solaṅkī invention. Raṅga-maṇḍapas consist of twelve pillars, arranged along the outer edge of the hall. They have an inner octagonal frame of architraves, supporting an elaborate corbelled ceiling (karōṭaka). This displays the lotus pendants described above. Alternatively, the raṅga-maṇḍapas can be double or multistoried and are then more commonly referred to as meghanāda-maṇḍapas (fig. 4).[12] These became especially popular throughout the region of northwestern India, from about the thirteenth century. In some examples, the open pillared hall has been detached from the main temple building. This can simply be a narrow gap or a wider cessation clearly setting apart the two building units.[13] When standing apart, the halls are also known as sabhā-maṇḍapa. Another architectural element, which has frequently been added along this axis of approach in Māru-Gurjara temples, is a freestanding gateway structure (toraṇa).[14]

Substantial temple edifices, consisting of a shrine and a closed and an open hall, recurrently have lateral porches. In most instances, these project from the front of the open and the sides of the closed hall. Furthermore, the central temple edifices are regularly housed inside protected courtyards. Since the mid-eleventh century, these have been delineated by sheltered colonnades, which are lined by small cells (devakulikās) housing additional statues.[15] The lines of interconnected shrines create sheltering walls, which physically protect the temple structures and shield them off from outside gaze (fig. 5).

The two most prominent building materials employed in Māru-Gurjara-style temples, are sandstone and marble. Whereas the sandstone employed can either be buff-colored or red, most marble used in Jaina structures is white.

Having summarized the main features of the Māru-Gurjara style of architecture, the following paragraph will introduce prominent examples of temples in this style from its formative and core phases in northwestern India.

Ars Orientalis Volume 45

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.