- Volume 45 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.3mb

Conclusion: Style and Identity

The Māru-Gurjara style, with its pronounced architectural, sculptural, and decorative features, is a rich and very distinct regional artistic style. Even though it has not been exclusively associated with Jaina constructions, and although there is no decorative style unique to Jainism, Jaina temples in this style reached a particularly high level of elaboration and refinement. It is the close association of the Māru-Gurjara style with Jaina temple building and with the survival and the wealth of the Jaina community in northwestern India that has led to a sizable number of large and famous temples constructed during this period. This, as well as the fact that in recent centuries Rajasthan and Gujarat have acquired a kind of homeland status for the Śvetāmbara community, have resulted in a firm association of Jainism with the Māru-Gurjara temple style.

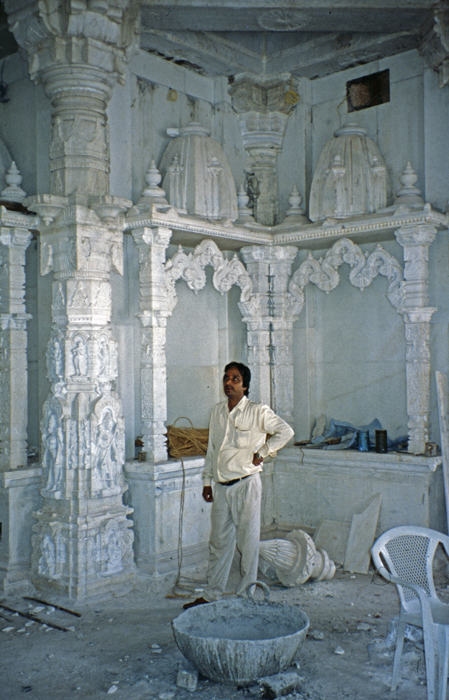

This is especially noticeable when Śvetāmbaras migrate to other regions of India—if in large numbers, such as the movement back into eastern India from the sixteenth century onward, or on a more individual level, as can be observed in central and southern India. In these new locations above all, Śvetāmbaras—but also Jainas more generally—regularly build temples that make clear reference to the medieval northwestern Indian Māru-Gurjara style (figs. 27a, 27b). This happens in spite of the presence of often equally rich and distinct local architectural traditions.

The fact that to a large extent Jainas consider this tenth- to thirteenth-century style of northwestern temple building typical and representative of their religion, if not the “Jaina temple style” par excellence, becomes evident when Jaina temples, raised in distant countries of the world, particularly in Eastern Africa and in Europe, show strong visual and stylistic affinities to this style.

One could argue that as the first specifically Jaina vāstu-śāstra or śilpa-śāstra texts were composed during the period of the Solaṅkī kings, the spread of this style can be explained through textual references. However, these religio-philosophical texts on architecture do not describe the stylistic features and decorations or the layout of maṇḍapas and porches, which are so characteristic of the style.[60]

It is striking that when found outside of Rajasthan and Gujarat, the individual building parts of temples in this style have often been carved by craftsmen from the Northwest. Yet it appears that it is not due to the wandering of northwestern Indian craftsmen who offer their services that the style has and is still spreading in this form. Rather, it is communities based in distant regions, who wish to commission temples in this historic style. In most instances, the planning and design is done by master architects locally and stone masons are drafted in. Teams of craftsmen from the area shaped by Solaṅkī influence are considered more skilled and versed in the Māru-Gurjara style and in working materials—white marble and sandstone—which are not widely available in all regions of the subcontinent.

Among the main reasons for the choice of style seems to be its visual appeal: it is a highly ornate, rich, distinct, and representative style. Also the political and historic associations connected with the typical Māru-Gurjara features appear to play a crucial role. Jaina culture and influence boomed under Solaṅkī rule, linking it permanently with the idea of a golden age and period of strength and superiority. Due to these positive connotations, Jainas reverted back to this style after the unsettling phase of external incursions, when large rebuilding campaigns resumed throughout the region from the fifteenth century onward, with a particular emphasis during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During the latter period, it was the Anandji Kalyanji Trust in particular that patronized temple reconstructions in this style, particularly in order to counterbalance the often strongly Islamicate style employed in Jain constructions during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. This irreversibly associated the grand pilgrimage centers of the Śvetāmbara community: Mount Śatruñjaya, Mount Girnār, Mount Ābū, Ranakpur, and others with the Māru-Gurjara style. This was then the image of Jaina architecture and of home that Jaina merchant families took with them on their migration to distant parts of the subcontinent and abroad, and this is the style of the temples that they visit when on pilgrimage back home.[61]

The strong connections between identity and style have been much discussed in the context of early Islamic art in India. The first congregational mosque built in Delhi under permanent Muslim rule, the Quwwatu’l Islām Masjid, effectively employs the shape of the pointed arch. Although the technical knowledge of how to construct a true arch was neither available to the early Muslim settlers nor to the local probably largely Hindu craftsmen, the shape of a pointed arch was carved out of a trabeate corbelled opening, illustrating the significance attached to stylistic features.

Jaina temples in the Māru-Gurjara style illustrate the same phenomenon that style and building layouts carry meaning and are understood by onlookers and users to express religious and political connotations. Whereas in India, the link to this style is of a more limited form, i.e., between the Śvetāmbara Jaina community and their home territory in northwestern India, the connection appears to become looser when Jainas migrate abroad. In the diaspora, Śvetāmbaras, Digambaras, and non-image worshipping groups of Jains often use the same places of worship and even share these with Hindus or Sikhs.[62] In this context, the Māru-Gurjara style becomes representative of all of these religions and of India as a whole.

An examination of the spread and continuity of the Māru-Gurjara style provides fertile ground for rethinking the routes and movement of Jaina architectural and spatial forms. More important than the independent migration of craftsmen, seem to have been the movement of Jaina merchant families and their conceptual and emotional link with this style. The creation of a demand and a market for a Māru-Gurjara continuation style in other areas of India and abroad has initiated the passage of artists across regional borders and the shipment of their carvings to other continents. Consequently, we are not dealing with an accidental diffusion. The situation outlined here shows a deliberate circulation of architectural forms and a selective reproduction of motives and spatial paradigms through a conscious commissioning of craftsmen reproducing a historic style filled with strong aesthetic, religious, and political associations.

Ars Orientalis Volume 45

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.