- Volume 45 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.3mb

Abstract

This article explores the transmission of architectural styles and building conventions in Jaina temple architecture from the medieval period to the present day. It focuses on the Māru-Gurjara (Solaṅkī) style of architecture, which evolved in northwestern India between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. Despite its originally clearly defined geographic and temporal remit, certain Māru-Gurjara features have become emblematic and symbolic of a glorious Jaina past. These spatial conventions and decorative elements have been employed during subsequent centuries to strengthen a Jaina cultural and religious identity. As part of its supra-regional application, the style was exported to other areas of the Indian subcontinent and taken abroad into the Jaina diaspora.

Introduction

The spatial layout of Jaina temples generally follows a common approach to structuring sacred and ritual space, which is not unique to a specific geographical region or period, but typical of Jaina sacred architecture as a whole.[1] In the surface decorations of façades and other building elements, however, the edifices usually reflect the local style prevalent during a given period and utilize locally available building materials.

While this is the general rule, there are some noteworthy exceptions where styles characteristic of a certain period or locality have consciously been reemployed elsewhere to establish deliberate references to the past—usually to what are regarded as particularly glorious periods—to influential patrons and to especially well-known sacred sites. These examples allow us to draw important conclusions about the significance of and the meanings attached to architectural idioms and reiterate that architecture, and above all styles, carry meanings and transmit messages to those seeing and using the edifices.[2] A particularly remarkable and widespread case of such a mobile set of architectural features is represented by the Māru-Gurjara or Solaṅkī style of architecture.[3] It first evolved in what are today the modern States of Rajasthan and Gujarat, during the period spanning from the tenth to thirteenth century. Art historians have regularly described this phase as the or at least one important high point of Jaina temple building. Fascinating for our enquiry is the special appeal and the religio-political associations, which this style appears to have for Jainas themselves.

This can be examined especially well when the style has been employed outside its original “home” territory. This is, for instance, the case in the sacred structures, which Jainas raised in the east of India when large sections of the community started returning to the region from the sixteenth century onward as well as in Jaina temples constructed in trading towns in central and southern India in recent centuries. The late medieval and modern temples raised by the Śvetāmbara Jaina community throughout the subcontinent recurrently employ a version of the northwestern Indian Māru-Gurjara style, despite the fact that the East, the central area and the South have their own distinct architectural traditions and prominent surviving ancient Jaina structures.[4]

One may argue that this is due above all to the mobility of the Mārwari Śvetāmbara Jaina community, who as merchants moved into these new territories and took with them the medieval style of their home region. However, also when Jainas went abroad, to Kenya, to Great Britain, to Belgium and to North America, they—and this is then usually a conglomerate of Śvetāmbara, Digambara and non-image worshipping Jaina groups—frequently construct temples imitating the style of architecture employed during Solaṅkī patronage. In many instances, a direct link to Gujarat and to north-western Indian craftsmen too can be established. In others, it is local workmen aiming to convey a distinct Māru-Gurjara impression.

The following discussion will stress the significant role that styles of architecture play in shaping identities and establishing ties with the past and with one’s home area (even if this is a perceived mythical home) and as such succeed in transgressing regional, national and temporal boundaries.

Style and Architecture under the Solaṅkī Rulers

Northwestern India has a long and intimate connection with the Jaina faith. According to Jaina history, the religion reached the western region of India already during the lifetime of Mahāvīra, the historic twenty-fourth Tīrthaṅkara or Jina who lived in about the sixth century BCE.[5] Despite a number of Islamic incursions,[6] Jainism and its temple structures continued to flourish during the eleventh to the thirteenth century, when the area was under the control of the influential Solaṅkī or Cāḷukya/Caulukya rulers.[7] The Solaṅkī or Māru-Gurjara style of architecture started as a regional form but soon acquired supra-regional dimensions. Due to its opulent decorative features, the style is easily recognisable and even if only a few of its essential elements have been reproduced, it triggers an immediate recognition.

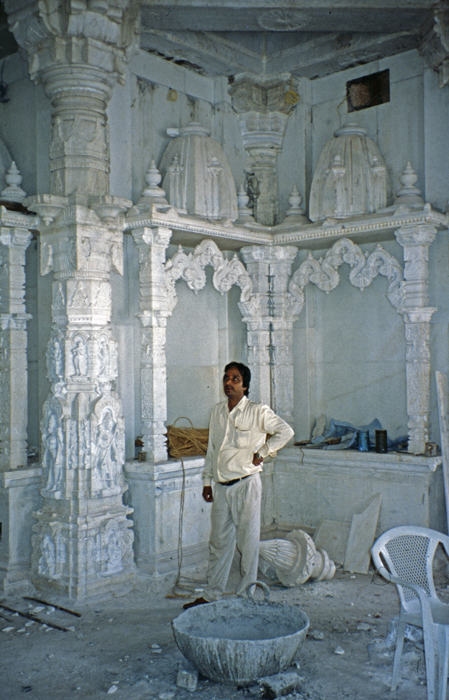

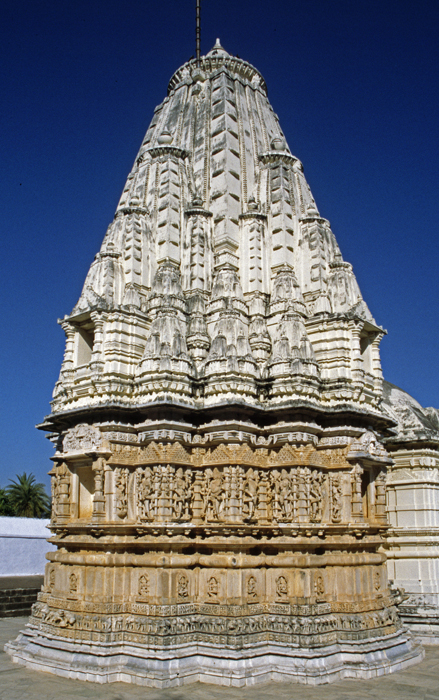

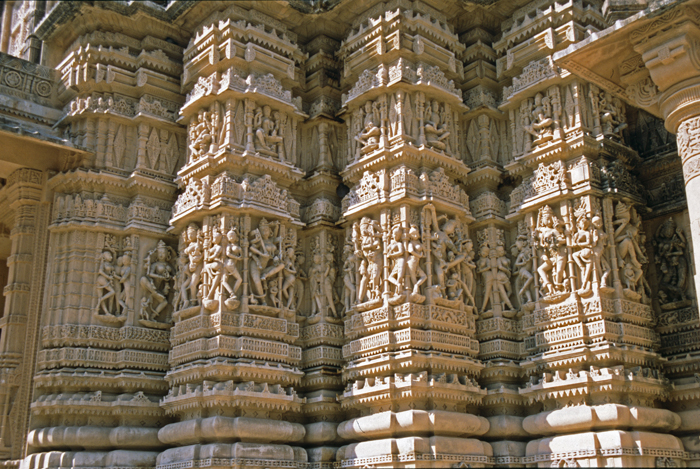

The Māru-Gurjara style is part of the northern Indian temple idiom, following the Nāgara design, in which the temple tower (śikhara) has a curvilinear shape (fig. 1). Both Hindu and Jaina temples were created following this style. Amongst its distinct features are that the external walls of the temples have been structured by increasing numbers of projections and recesses, accommodating sharply carved statues in niches. These are normally positioned in superimposed registers, above the lower bands of moldings (fig. 2). The latter display continuous lines of horse riders, elephants, and kīrttimukhas.[8] Hardly any segment of the surface is left unadorned.

Visually even more pronounced is the interior design of temples raised under Solaṅkī patronage. Typically, these have large, open pillared halls, which are lavishly ornamented. On the plan, the pillars are arranged in an octagonal shape and are carved from top to bottom with profuse decorations. These include floral and vegetal ornamentation, geometric design patterns, and many figural representations. Carved sculptures are finely cut and often heavily decorated. Sculpted figures adorn brackets projecting from the upper section of the pillars. Frequently, ornamental arches displaying a multi-cusped design have been thrown across the pillars forming the central octagonal area. These are known as aṇḍolā and resemble the design of a toraṇa (an ornamental gateway). The same kind of flying arches have also regularly been positioned between pillars framing the entrance or the sides of porches. Through this, a predominantly interior feature become part of the external appearance of temples. Besides, the ceiling panels of halls and ambulatories in this style have been lavishly decorated. Particularly famous are the domical ceilings formed out of diminishing concentric rings, following a trabeate (corbelled) construction technique.[9] From the center of the ceiling usually projects a large carved stone lotus pendant (padma-śila).[10] Some domical ceilings have multiple stalactite-like lotus projections. Jaina examples of such elaborate ceilings often display figural representations of the goddesses of learning and knowledge (vidyā-devīs).[11]

Although the decorative features of this medieval western Indian style are especially pronounced and representative and have consequently been copied most consistently, there are additional structural features, which typify the temples raised under the patronage of the Solaṅkī kings. The elements discussed above—profusely carved pillars, ceilings and flying arches—are particularly visible in the large, open pillared halls, which gained a specific prominence in complex Māru-Gurjara temples. Many Jaina temples have one closed and two pillared halls, further elongating the axis of approach to the principal shrine (fig. 3). Of these halls, the one closest to the compound entrance is in most instances raised on a slightly lower terrace than the more sacred building elements of the temples. These halls, which are designed to accommodate dance and dramatic performances as well as communal worship, are referred to as raṅga-maṇḍapas and are considered to be a Solaṅkī invention. Raṅga-maṇḍapas consist of twelve pillars, arranged along the outer edge of the hall. They have an inner octagonal frame of architraves, supporting an elaborate corbelled ceiling (karōṭaka). This displays the lotus pendants described above. Alternatively, the raṅga-maṇḍapas can be double or multistoried and are then more commonly referred to as meghanāda-maṇḍapas (fig. 4).[12] These became especially popular throughout the region of northwestern India, from about the thirteenth century. In some examples, the open pillared hall has been detached from the main temple building. This can simply be a narrow gap or a wider cessation clearly setting apart the two building units.[13] When standing apart, the halls are also known as sabhā-maṇḍapa. Another architectural element, which has frequently been added along this axis of approach in Māru-Gurjara temples, is a freestanding gateway structure (toraṇa).[14]

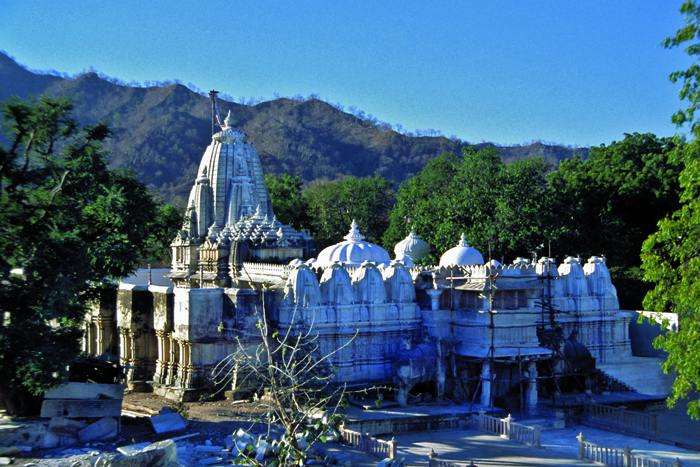

Substantial temple edifices, consisting of a shrine and a closed and an open hall, recurrently have lateral porches. In most instances, these project from the front of the open and the sides of the closed hall. Furthermore, the central temple edifices are regularly housed inside protected courtyards. Since the mid-eleventh century, these have been delineated by sheltered colonnades, which are lined by small cells (devakulikās) housing additional statues.[15] The lines of interconnected shrines create sheltering walls, which physically protect the temple structures and shield them off from outside gaze (fig. 5).

The two most prominent building materials employed in Māru-Gurjara-style temples, are sandstone and marble. Whereas the sandstone employed can either be buff-colored or red, most marble used in Jaina structures is white.

Having summarized the main features of the Māru-Gurjara style of architecture, the following paragraph will introduce prominent examples of temples in this style from its formative and core phases in northwestern India.

Māru-Gurjara Jaina Temples in Northwestern India

Jainism enjoyed one of its most prosperous times under the Cāḷukya Solaṅkī kings. The earliest major surviving temple construction in the Māru-Gurjara style, is the temple of Ādinātha, better known as the Vimala-vasahī on Mount Ābū.[16] It was commissioned by Daṇḍanāyaka Vimala, (Vimala Śāha), a minister and commander-in-chief under the Solaṅkī ruler Bhīma Rājā I, alternatively known as Bhīmdeo (1022–1064 CE) in 1032 CE.[17] The garbha-gr̥ha and the closed and open halls were constructed during the foundation of the temple in the eleventh century and the remaining parts were added during the twelfth century.

In the eleventh century too, a series of Jaina temples were raised at Kumbharia in Rajasthan. Two constructions at the site are relatively firmly dated, the Mahāvīra temple to 1062 CE and the Śāntinātha temple to 1082 CE. During the reign of the Śaiva king Siddharāja Jayasiṁha (1094–1144 CE), Jainism prospered, and two more temples were erected at the site. The Pārśvanātha temple has been dated to 1105 CE, and the Neminātha temple to 1136 CE (see fig. 1). The prosperity and large building projects of the Jainas during this period, however, were overshadowed by series of raids and by the Islamic occupation of Gujarat.[18]

During the twelfth century, prominent Jaina temples in the Māru-Gurjara style were constructed in Gujarat, at sites such as Patan, Dholka, Siddhapura, Sejakpur, and on Mount Girnār.[19] Despite several renovations, substantial parts of the early structure of the Neminātha temple (1128 CE) on Girnār still remain. Also in Rajasthan, the twelfth century was a prosperous period, in which many new temples were constructed under the rule of the Śākambharī Cāhamānas and the Cāhamānas of Nadol and Jalor.[20]

One of the greatest supporters of Jainism in the area was Siddharāja’s successor, the Cāḷukya king Kumārapāla, who ruled Gujarat between 1144 and 1174 CE.[21] He constructed a large number of small Jaina shrines in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and even beyond this region as part of the propagation of Jainism.[22] The main incentive for these building activities seems to have been to support the propagation and expansion of the faith through an even distribution of small places of worship instead of the establishment of a few major places of pilgrimage at selected and widely dispersed sites. Originally, small and simple shrines were modified and expanded during later centuries. Most Jaina temples commissioned by Kumārapāla are now lost or are difficult to identify. This is largely due to the destruction of many temple sites, the absence of inscriptions, which would help to identify them, and due to the continuous implementation of substantial renovations, which Jaina temples habitually and repeatedly undergo throughout their history.[23] A celebrated case of a comparatively large and well-preserved temple structure, which was founded by kind Kumārapāla and nonetheless survives, is the Ajitanātha temple at Taranga (1164–66 CE) in Gujarat.[24] In addition to the direct patronage instigated by the king himself, his ministers too funded Jaina temple constructions and additions to earlier shrines. The open hall, known as nr̥tya-maṇḍapa, located in front of the Vimala-vasahī, is a good example. It was added by his minister Pr̥thvīpāla in 1150 CE .[25]

Royal and state support for Jainism was largely lost after Kumārapāla. His son Ajayapāla, who succeeded to the throne in 1173 CE, is thought to have been opposed to Jainism and even to have destroyed Jaina edifices.[26] At state level, the situation did not much improve when political power passed from the Cāḷukyas to the Vāghelās. Privately, however, Vastupāla and Tejapāla, two brothers serving as ministers first to Bhīma Deva II (1178–1241 CE) and then to his son Vīradhavala, continued to construct major Jaina edifices and to repair and rebuild earlier constructions .[27] The list of temples raised or renovated by them is extensive, with many surviving at places such as the sacred hills of Girnār and Ābū and at Kumbharia and Sarotra in Rajasthan.[28] Amongst their best-known commissions are the Neminātha temple, constructed in 1231 CE on Mount Ābū, and the Mallinātha temple on Mount Girnār, founded in 1232 CE but having many later additions.[29]

It has been argued that there were no great Jaina patrons after Vastupāla and Tejapāla in this region in the thirteenth century. However, Jagaḍu, a prominent Jaina merchant at the time, had the Jaina temple at Bhadreshvar in Gujarat constructed in the middle of the thirteenth century (1248 CE).[30] Other individuals, such as the Jaina saint Pethaḍa of Mandu, who is believed to have erected about eighty-four Jaina temples, many at sites in western India, his son Jhānjhaṇa, as well as the Paramāra kings of Malwa, were sympathetic to Jainism and continued the tradition of enlarging ancient Jaina sites of pilgrimage and founding new establishments.[31] By the twelfth to thirteenth century, Jainism had become so deeply rooted as one of the dominant religions in the area, that the withdrawal of centralized support could be compensated for by the local community.[32] Hema Rāja of Bikaner had the Susānī Temple at Morkhana in Rajasthan repaired, and in 1280 CE several newly commissioned Jaina statues were installed in various temples in Ajmer, also in Rajasthan. At other sites, entirely novel building projects were undertaken during this period, illustrated by the numerous temples commenced during this period inside the Adīśvara Tunk on Mount Śatruñjaya.[33]

The Renaissance of the Māru-Gurjara Style

Due to its intricate nature and strong aesthetic appeal as well as its close association with what became to be regarded as a “golden age” of Jainism,[34] architectural and decorative features associated with the Māru-Gurjara style continued to be employed well beyond its initial temporal and geographical remits. Rather than representing an unconscious and accidental process of diffusion or influence, builders were actively employed to rebuild or construct temples, which reproduced the typical temple layout in addition to selective decorative features and motives developed under Solaṅkī patronage as a form of stylistic citation. This placed the rebuilt and newly founded temples in a transregional network of Jaina sites all largely following one characteristic style.

Northwestern India

In Rajasthan and Gujarat, the cradle of Māru-Gurjara temple architecture, the style ceased to flourish extensively in the thirteenth century. However, it is clear from the available architectural evidence, that after a short hiatus, it experienced a revival within the area of northwestern India already in the fifteenth century.[35]

During the rebuilding and reconstruction of destroyed Jaina temples on the sacred mountains of Śatruñjaya, Girnār and Ābū as well as at the Rajasthani sites of Chitorgarh, Jaisalmer, Varkana, Sirohi, Ahar, and Mirpur (fig. 6) and in Gujarat at Sabli, Abhapur, Atarsumbha, and Raigarh—just to mention a few—the Māru-Gurjara style was reemployed. One of the best-known fifteenth-century Jaina temples reinterpreting this style is the Ādinātha temple at Ranakpur, founded in 1439 CE (fig. 7).

During this period, the Māru-Gurjara style, which had originally been associated with a high point of Jaina influence and artistic proficiency, gained an additional positive association, that of the resistance and survival of Jainism against all odds. It will be argued in this paper that the combination of a clearly defined, rich and appealing style with the political associations of strength and issues of identity guaranteed the continuous popularity of the Māru-Gurjara style. Due to these correlations, the style has continuously been employed since the fifteenth century and up to the present day.

On this basis, enigmatic stylistic features were continued in the building activities of the sixteenth-century Candraprabhu and Aṣṭāpada temples at Jaisalmer; the seventeenth-century rebuilding phase of the Pārśvanātha temple at Lodruva[36]; and the well-known nineteenth-century temples in Ajmer and Ahmedabad (fig. 8)—the Nasinyān or Soni Jaina temple and the Śeṭh Hāthīsiṅgh temple. Also in the course of the nineteenth century, large-scale renovation and rebuilding campaigns on sacred Mount Śatruñjaya in Gujarat, financed largely by the Anandji Kalyanji Trust, contributed further to the fostering, promotion, and the further establishment of the style, its close association with the Jaina community in western India, and the glorification of the style as representative of a golden age.[37] Fascinating twentieth-century Māru-Gurjara-style imitation temples are the Pārśvanātha temple at Bakara Road and the Pāvāpurī temple at Krishnaganj (figs. 9, 25b), both in Rajasthan. Even temples that follow an entirely different planning logic, such as the havelī or hall-type plan,[38] can have façades following the ideals of the Māru-Gurjara style, as may be seen in the Munisuvrata temple at Narlai and in the Pāvāpurī Jal temple at Sadri, both in Rajasthan.

There is no specific association between the Śvetāmbara group of Jainas and the Māru-Gurjara style in northwestern India as Digambara Jaina temples have also habitually been designed in this style. This applies both to the first flowering of the style as well as to Digambara temples during later periods. The latter case is exemplified by the exterior surface treatment of temples such as the Mahāvīra Digambara temple at Mahavirji, the devakulikā cells of the twentieth-century Śāntinātha Digambara temple at Shanti Vir Nagar, and many of the decorative features (e.g., flying arches, bracket figures, carved pillars, lotus ceilings etc.) of the largely sixteenth-century Digambara temples at Sanganer, all in Rajasthan.

Even more crucial for the discussion in this essay on the transmission of architectural knowledge, however, is the mobility of this style not just beyond its initial temporal but as much beyond its regional remit. This issue will be analyzed in the following sections.

North and Eastern India

Without a thorough knowledge of the Māru-Gurjara style and medieval architectural developments under the Solaṅkī rulers in northwestern India, a large number of temple constructions dating from the sixteenth and later centuries in the North and particularly in the East of India cannot adequately be understood. Jainas who, largely for trade reasons, migrated from Rajasthan and Gujarat to the East from about the sixteenth century onward brought with them many of the aesthetic conventions and stylistic features characterized by Māru-Gurjara principles of architecture.[39]

The temples raised at ancient sites of Jaina significance, such as Vaishali and Kundalpur in Bihar,[40] just as new foundations in the residential neighborhoods of Jaina trading centers, such as Calcutta, Cuttack, and Murshidabad, regularly employ idioms reminiscent of the Māru-Gurjara style. Even though there are large numbers of temples in this style throughout the region, I will focus on a selection of eight temples, which illustrate the key issues exceptionally well. Four of the temples are located in Delhi, Haryana (Hastinapur), and Uttar Pradesh (Varanasi and Sravasti) in the North, and four come from the East, from Bihar (Kundalpur, Pavapuri, Madhuban) and Orissa (Cuttack). The Dādā Bāṛī Jaina temple complex in Mehrauli in the south of Delhi[41] has an ancient history although the complex of open halls, which are of interest to the discussion in this essay, were raised in the late 1930s (fig. 11).[42] The funds for the Śrī Cintāmaṇī Pārśvanātha Śvetāmbara temple at Hastinapur were donated in 1929 with the structure dating largely from the 1990s. Also from the 1990s are the New Śvetāmbara Pārśvanātha temple (no. III) in Bhelupura in Varanasi, founded in 1999 and the Śvetāmbara Sambhavanatha temple at Sravasti. Slightly earlier are the Ādinātha Śvetāmbara Jaina temple at Kundalpur (fig. 15), constructed in 1985, and the Śrī Samavasaraṇa Bīs Jinālaya at Madhuban consecrated in about 1987 (Śamvat 2043). Dating from the 1970s are the Śvetāmbara Gāṁv Mandir at Pavapuri, which was substantially rebuilt and renovated in 1975 and the Neminātha temple in the Kaji Bazaar area of Cuttack, which was started in 1974 (fig. 10).

All but the temple from Madhuban display the triple porches, which are so typical of temples constructed under Solaṅkī patronage. As in northwestern India, two are positioned laterally and one at the front of the temple. Jaina temple constructions in the North and East, which follow the maṇḍapa-line layout,[43] are generally simpler than those in the region of northwestern India. Consequently, there are relatively few examples with multiple aligned maṇḍapas, a feature, which is so characteristic of Māru-Gurjara-style temples, which regularly have lines of three or four halls. An exception is the modern Śvetāmbara Sambhavanātha temple at Sravasti, which has an additional shallow open hall (fig. 12).[44] Even rarer are temples with more than two halls and a porch. The few available occurrences are in the main very recent constructions. The dādā-bāṛī (‘garden of the Dādā’), a religious structure dedicated to a dādā-guru in Delhi has an unusual sequence of open halls, bordering the main temple building.[45] At the centre of this multiple maṇḍapa arrangement stands a small pavilion, commemorating the samādhi, the final liberation, of Śrī Maṇidhārī Jinacandra Sūrijī.[46] The architectural structure, which follows the logic of a Jaina temple, is not a proper shrine but in fact a memorial. It consists exclusively of interlinked halls and is an architectural celebration of open maṇḍapas in the Māru-Gurjara style (fig. 11). The Śrī Samavasaraṇa Bīs Jinālaya, alternatively known as the Śikharjī temple at Madhuban illustrates the presence of devakulikā chapels surrounding a central temple building as a further typical Māru-Gurjara spatial feature (fig. 13).

In addition to this planning paradigm, shaped by features developed under Solaṅkī rule, the temples employ medieval northwestern Indian temple decorations. Particularly elaborate carved pillars with figural representations are seen in the temples in Varanasi and Pavapuri (fig. 14), and most display the characteristic flying arches. The temples also have elaborately decorated domical ceilings in a lotus design, of which some even reproduce the central projecting pendant, as can be seen in the temples at Kundalpur, Varanasi, and Pavapuri.[47] Another Māru-Gurjara feature is that the edifices have either been constructed of white marble or sandstone of varying shades of yellow and pink. It is fascinating to observe that although many Jaina temples today are largely metal and concrete constructions, their façades have been clad with thin white marble or red sandstone facings, making direct reference to and conveying the image of medieval Jaina temple constructions. Taken out of context, any connoisseur of Jaina temple architecture would place these structures in the architectural tradition of northwestern India, as the edifices—all constructed by the Śvetāmbara community—clearly aim at replicating a Māru-Gurjara ideal.

An additional link to the Northwest is provided by the fact that it is not only the layout, decorations, and material of these temples that resemble a northwestern style. As marble and sandstone are not naturally available in large quantities in eastern India, the building material, and in many cases even the workmanship and expertise, have been directly imported from the Northwest. The pink sandstone used for the outside and the white marble cladding on the inside of the Śvetāmbara Gāṁv Mandir at Pavapuri were imported from Rajasthan. The yellow sandstone for the construction of the Śvetāmbara Ādinātha temple at Kundalpur was quarried, cut, and carved in all its detail at Jaisalmer, transported to Bihar in its finished form and assembled on site (fig. 15).[48] The pink sandstone and the white marble for the new Śvetāmbara Pārśvanātha temple in Varanasi come from Sirohi and Jaipur, and the workmen carving the stone on site in Varanasi came from Jaisalmer to where they returned after the project had been completed.

Many of the Jaina temples in northern and eastern India, as well as in central and southern India, house sculptural representations that are closely connected with certain clearly identified sites in the northwest of the country. These are, for instance, the Jinas Ludrava Pārśvanātha and Śaṅkeśvara Pārśvanātha.[49] Interestingly, also the guardians of the sacred temple complex, the kṣetra-pālas Nākoḍā Bhairava and Ghaṇṭākarṇa Vīr or Ghaṇṭākarṇa Mahāvīra are particularly popular in northwestern India and have consequently been taken wherever the Śvetāmbara community has migrated.[50]

Statues of these specific Jinas and kṣetra-pālas were exported along with the Māru-Gurjara style. Images of sacred pilgrimage sites were reproduced too. In this way, the sacred sites associated with the home country of Śvetāmbara Jainas—i.e., northwestern India, with its tightly knit network of holy pilgrimage sites—became portable. Wherever Śvetāmbara merchant communities migrate, representations of their sacred hills Śatruñjaya, Girnār, and Ābū are taken, installed, and venerated as symbols of communal origin and religious identity.

Central India and Southern India

Jaina temple structures in central India typically follow a compact and centralized planning concept.[51] Therefore, the Māru-Gurjara paradigm of having multiple axially aligned halls with associated porches is relatively uncommon and rare. Most temples displaying combinations of maṇḍapas and porches in this region are modern temple buildings, dating largely from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and are more likely to have been designed for a Śvetāmbara than a Digambara audience. The Digambara community clearly is in the majority in central India. Pockets of Śvetāmbara Jaina groups, usually in larger cities, consist on the whole of merchant families who have moved there from northwestern India. To a large extent, they define the aesthetic and religious environment of their temples in terms of their home territory.

As was the case in northern and eastern India, discussed in the previous section, many of these temples follow the layout of having a shrine and an attached hall, giving way to three porches. This can be seen in the Śītalanātha temple at Saraphbazaar in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, and in Maharashtra in the Pārśvanātha temple in Sholapur and the Munisuvratnātha temple in Kolhapur (fig. 16a). In the Ādinātha temple at Kulpak in Andhra Pradesh, a very shallow open hall and in the Śrī Hiṅkār Pārśvanātha temple in Nambur at Nagarjunanagar, Andhra Pradesh, a slightly deeper open hall has been inserted between the closed hall and the front porch.[52] The Supārśvanātha temple at Mandu has a closed and a proper open raṅga-maṇḍapa (fig. 16b). Even temples which do not overtly display a Māru-Gurjara style can have toraṇa arches marking the entrance to the sacred compound, as is the case in the Pārśvanātha Śvetāmbara temple in central Mumbai.

However, many temples in central and southern India do not follow this maṇḍapa-line temple layout but still display the visual appeal developed under the Solaṅkī rulers, in their material and decorative features. The Ādīśvarjī temple in Bombay and the Vāsupūjyasvāmī temple in Madras are complex double-storied constructions (fig. 17).[53] There also are domestic house-style temples, such as the Śrī Ādinātha temple in Madras, Tamil Nadu, and the Sumatinātha temple in Margaon in Goa, which follow this planning ideal yet have façades in the Māru-Gurjara style (figs. 18a, 18b).[54]

The Śvetāmbara temples in the central region of India have mostly been built of or clad with white marble or sandstone. Among the temple structures mentioned already, those at Mandu, Bombay, Sholapur, Kolhapur, Madras, and Margaon are white marble temples and those at Jabalpur, Kulpak, and Nagarjunanagar (fig. 19) are sandstone examples.

In their surface decorations and the ornamentation on the interior too, they resemble northwestern Indian Māru-Gurjara architecture by having elaborately decorated pillars, frequently employing figural representations. Particularly evolved again are the flying arches. In the Vāsupūjyasvāmī temple in Madras and in the Sumatinātha Śvetāmbara temple in Margaon, these have been employed on superimposed levels in the façade. Most of the temples have elaborately carved domical ceilings, often employing lotus designs with central pendants and brackets displaying the goddesses of learning. Even temples in which exterior references to the Māru-Gurjara style are relatively muted, regularly have corbelled lotus ceilings, as is exemplified by the Śāntinātha temple at Mandu. On a regular basis, the lotus design of the ceiling has been mirrored in the floral design of the inlaid marble floors beneath.

The discussion in the previous section, tracking the spread of the Māru-Gurjara style throughout India, has shown, that whereas Digambara Jainas in northwestern India also employ or at least make reference to the Māru-Gurjara style during later periods, it is relatively uncommon to find Digambaras in other areas of the subcontinent using Māru-Gurjara decorative features. Whereas in northwestern India, the architectural and decorative style developed under the Solaṅkī rulers seems to be perceived as a local regional style that is open to all, it appears largely to be the Śvetāmbaras who identify with it and reproduce it when they migrate to other parts of India. This might equally have to do with the fact that it is the Mārwari Śvetāmbara Jaina community specifically, who has migrated from northwestern India in large numbers. The following discussion will illustrate that the situation is slightly less rigid when it comes to Jainas migrating abroad.

Exporting Māru-Gurjara Features to Africa and the West

The Māru-Gurjara style of architecture did not cease to exist in the thirteenth century, and it clearly spread to other areas of India. However, neither the Jaina community nor its popular architectural style stopped there. Due particularly to trading links, the Jaina community extends worldwide; for example, large groups settled in East Africa, North America, the United Kingdom, and various other European countries. Wherever the Jainas went, they took elements of their mythical home country in northwestern India.

Particularly remarkable is that while in India, the style was almost exclusively associated with Śvetāmbara Jainas, there is not such a clear division in the diaspora. The Jaina temple in Leicester in the United Kingdom, for example, is frequented by Śvetāmbaras, Digambaras and members of non-image-worshipping factions of the Jaina community (fig. 20). Still, the temple—housed in a former Anglican church—displays the hallmarks of the Māru-Gurjara style.[55] This can be seen in its façade, which has been clad in profusely decorated white marble, and in the large hall located on the first floor, which accommodates a substantial number of decorated marble pillars with prominent flying arches.[56]

Striking instances of purpose-built temples directly replicating the Māru-Gurjara style in the diaspora, are the Jaina temple in the complex of the Oshwal Mahajanwadi in Nairobi (fig. 21) and the Derasar in Mombasa (constructed between 1990 and 1998) in Kenya. The first is a sandstone construction and the second has largely been clad in white marble. Both are Nāgara temples, closely reproducing a Māru-Gurjara image. Following the same aesthetic is the sandstone Jaina Derasar of the Oshwal Centre in Potters Bar, in Britain (fig. 22). Probably the largest temple in the Māru-Gurjara style outside India, is in Wilrijk on the outskirts of Antwerp in Belgium (fig. 23). The statues were officially installed in August 2010. The Śvetāmbara white marble structure dedicated to Pārśvanātha is raised on a tall terrace, has a central as well as two lateral śikhara towers, walls with niches and figural representations, and porches with carved pillars and flying arches (fig. 24). The building elements and statues were all carved in India and transported to Europe where they were simply assembled and consecrated.

Jaina temples in North America usually show a slightly less immediate response to the Māru-Gurjara style, although in the detail, more subtle echoes can be found too. The temple of the Jain Society of Greater Detroit in the United States was completed in 1998. It is a white plastered edifice with a white marble Nāgara śikhara tower, which was shipped over from India. On the inside, the temple has carved pillars and niches surrounding the sizeable hall, but otherwise, it is largely a modern Western edifice. It is fascinating that instead of lotus pendants, there are glass chandeliers protruding from the ceilings, representing a more independent interpretation of an ancient theme. Also in Canada, for example, in the joint Śvetāmbara-Digmbara Jaina Temple in Toronto the Māru-Gurjara influences are relatively muted.

This raises the question why the Māru-Gurjara influence is still so much stronger in Kenya and in Europe than it appears to be in many Jaina temples in the United States and in Canada. Japan seems to follow a similar approach. Is it because Jainism reached the United States via Eastern Africa and Europe and displays architecture, which is further removed in space and time from the home country of the Mārwari Jainas?[57] Or is it that one is more hesitant in America with its strong Christian orientation to construct overtly foreign and non-Christian looking architecture? This would at least explain why the exterior of these temples is usually more plain or even resembles the outer shape of churches, as is the case in the Toronto Jaina temple. Stronger Indian and Māru-Gurjara tones are generally only noticeable in the interior of these North American Jaina temples.

Re-use of Other Regional Styles

The Māru-Gurjara style of temple building is the most prominently re-used temple style employed by the Jaina community. However, it is not the only regional form of building, which has been revived at places elsewhere. Although the emphasis in this article clearly is on the north-western Indian temple style, for the sake of widening the debate and encouraging further related studies in the future, I would like to raise a few issues with regards to other styles.

Two other regional styles show a certain popularity and distribution and may be used as a point of reference in Jaina temple architecture. The first is the Marāṭhā style of architecture, which originated largely in seventeenth-century Maharashtra and reached a zenith under the Marāṭhā Peśvās during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Marāṭhā style of architecture had a marked influence on the layout and the decorations of Jaina temples in central India. Although there are temples that make reference to Marāṭhā temple features, particularly in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, these are comparatively rare and the style has not gained a specifically Jaina importance outside its immediate geographical area. This may partly be due to the fact that the style as a whole is much less clearly defined than the Māru-Gurjara idiom and that it clearly is a hybrid style itself. The Marāṭhā style integrates strong elements from Mughal architecture, such as bangala roof shapes, a structuring of the façades of temples into cassettes (frames), pavilions, white wash, and white marble carved in Mughal-style designs. This can, for instance be seen in the Sumatinātha temple at Ayodhya (fig. 25a), the Pārśvanātha temple at Allahabad, the Śāntinātha temple in Faizabad, and the Ajitnatha temple at Batesar (Bateshvar), all in Uttar Pradesh. Especially when found in the Mughal area of influence, it is not clear whether the reference is to Mughal and to Shāh Jahāni stylistic features more directly or to the central Indian continuity style. Marāṭhā-style śikhara towers, which are more pyramidal and straight-sided with relief decorations, are also encountered in Karnataka, as may be seen in the Cintāmaṇī Pārśvanātha temple in Babanagar in northern Karnataka (fig. 25b). In the latter case, however, the geographic vicinity to the Marāṭhā region is so close, it is difficult to argue for a wide diffusion of the style as the examples and the style are much less clearly defined. Consequently, the evidence for the conscious use of the Marāṭhā style in Jaina temples in other regions is much less pronounced.

Other temples make references to certain features of South Indian temple designs. Again, we are not dealing with one concrete, strictly delineated style, but with a more vague idea of aspects of the South Indian tradition more generally. It can be the roof-structures of temples, which can make reference to Drāviḍa temples, as it is the case in the Svayambū Jaina Temple at Bahubali (Kumbhoj) in Maharashtra and in the Munisuvrata and Mahāvīra double temple on Vaibhāra Hill at Rajgir in Bihar. This has a vimāna-style pyramidal roof structure, which, however, is related to the shape of Jaina samavasaraṇas as well.[58] Even more common are references to Nāyaka pillared maṇḍapas, which have been alluded to in the halls of a number of Jaina temples outside the immediate Tamil territory. This can be seen in the Śvetāmbara Cintāmaṇī Pārśvanātha Jaina temple in Roshan Mohalla in Agra and in the Mahāvīra temple in Firozabad, both in Uttar Pradesh, and in the Pārśvanātha temple on the northern outskirts of Bijapur (fig. 26a). While the latter temple is located in the south of India, it clearly lies outside the Tamil Drāviḍa stylistic area. According to the caretaker of the shrine, the workmen who rebuilt the temple came from Madras. He proudly stressed, that the vimāna of this Jaina temple was a direct replica of the tower crowning the Bālājika Mandir at Tirupati in Tamil Nadu (fig. 26b). This is an alternative name for the Veṅkaṭēśvara temple at Tirumala near Tirupathi, Andhra Pradesh. Dedicated to the Hindu god Viṣṇu (Bālāji, Veṅkaṭēśvara), this is one of the Divya Deśam, the 108 “divine places” or sacred Viṣṇu temples, and as such one of the most sacred and regularly visited shrines of modern Hinduism. The special significance of the temple derives from the belief that the statue of the deity will remain inside the temple for the entire extent of the kali-yuga, the fourth and last stage of the world before its destruction. For Jainas too, the kali-yuga has particular meaning and the statue enshrined in the Digambara temple at Bijapur is a Śrī 1,008 Sahasra-phaṇa Pārśvanātha—a Jina sheltered by 1,008 snake heads. The statue has been credited with magical capacities. Other temples make reference to Deccani and Hoysala-style flat-roofed pillared halls, as can be seen in the Ādinātha temple in Golakot and the Old Caubārā Dehrā in Un, both in Madhya Pradesh.[59]

Though the refashioning of the Māru-Gurjara style of building is not unique, it still represents a special case as in its original form, it is a clearly defined style, derived from a small area and short temporal range which achieved by far the widest popularity and distribution within the subcontinent and abroad. In the following section, the specific appeal of this style for the Jaina community will be analyzed.

Conclusion: Style and Identity

The Māru-Gurjara style, with its pronounced architectural, sculptural, and decorative features, is a rich and very distinct regional artistic style. Even though it has not been exclusively associated with Jaina constructions, and although there is no decorative style unique to Jainism, Jaina temples in this style reached a particularly high level of elaboration and refinement. It is the close association of the Māru-Gurjara style with Jaina temple building and with the survival and the wealth of the Jaina community in northwestern India that has led to a sizable number of large and famous temples constructed during this period. This, as well as the fact that in recent centuries Rajasthan and Gujarat have acquired a kind of homeland status for the Śvetāmbara community, have resulted in a firm association of Jainism with the Māru-Gurjara temple style.

This is especially noticeable when Śvetāmbaras migrate to other regions of India—if in large numbers, such as the movement back into eastern India from the sixteenth century onward, or on a more individual level, as can be observed in central and southern India. In these new locations above all, Śvetāmbaras—but also Jainas more generally—regularly build temples that make clear reference to the medieval northwestern Indian Māru-Gurjara style (figs. 27a, 27b). This happens in spite of the presence of often equally rich and distinct local architectural traditions.

The fact that to a large extent Jainas consider this tenth- to thirteenth-century style of northwestern temple building typical and representative of their religion, if not the “Jaina temple style” par excellence, becomes evident when Jaina temples, raised in distant countries of the world, particularly in Eastern Africa and in Europe, show strong visual and stylistic affinities to this style.

One could argue that as the first specifically Jaina vāstu-śāstra or śilpa-śāstra texts were composed during the period of the Solaṅkī kings, the spread of this style can be explained through textual references. However, these religio-philosophical texts on architecture do not describe the stylistic features and decorations or the layout of maṇḍapas and porches, which are so characteristic of the style.[60]

It is striking that when found outside of Rajasthan and Gujarat, the individual building parts of temples in this style have often been carved by craftsmen from the Northwest. Yet it appears that it is not due to the wandering of northwestern Indian craftsmen who offer their services that the style has and is still spreading in this form. Rather, it is communities based in distant regions, who wish to commission temples in this historic style. In most instances, the planning and design is done by master architects locally and stone masons are drafted in. Teams of craftsmen from the area shaped by Solaṅkī influence are considered more skilled and versed in the Māru-Gurjara style and in working materials—white marble and sandstone—which are not widely available in all regions of the subcontinent.

Among the main reasons for the choice of style seems to be its visual appeal: it is a highly ornate, rich, distinct, and representative style. Also the political and historic associations connected with the typical Māru-Gurjara features appear to play a crucial role. Jaina culture and influence boomed under Solaṅkī rule, linking it permanently with the idea of a golden age and period of strength and superiority. Due to these positive connotations, Jainas reverted back to this style after the unsettling phase of external incursions, when large rebuilding campaigns resumed throughout the region from the fifteenth century onward, with a particular emphasis during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During the latter period, it was the Anandji Kalyanji Trust in particular that patronized temple reconstructions in this style, particularly in order to counterbalance the often strongly Islamicate style employed in Jain constructions during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. This irreversibly associated the grand pilgrimage centers of the Śvetāmbara community: Mount Śatruñjaya, Mount Girnār, Mount Ābū, Ranakpur, and others with the Māru-Gurjara style. This was then the image of Jaina architecture and of home that Jaina merchant families took with them on their migration to distant parts of the subcontinent and abroad, and this is the style of the temples that they visit when on pilgrimage back home.[61]

The strong connections between identity and style have been much discussed in the context of early Islamic art in India. The first congregational mosque built in Delhi under permanent Muslim rule, the Quwwatu’l Islām Masjid, effectively employs the shape of the pointed arch. Although the technical knowledge of how to construct a true arch was neither available to the early Muslim settlers nor to the local probably largely Hindu craftsmen, the shape of a pointed arch was carved out of a trabeate corbelled opening, illustrating the significance attached to stylistic features.

Jaina temples in the Māru-Gurjara style illustrate the same phenomenon that style and building layouts carry meaning and are understood by onlookers and users to express religious and political connotations. Whereas in India, the link to this style is of a more limited form, i.e., between the Śvetāmbara Jaina community and their home territory in northwestern India, the connection appears to become looser when Jainas migrate abroad. In the diaspora, Śvetāmbaras, Digambaras, and non-image worshipping groups of Jains often use the same places of worship and even share these with Hindus or Sikhs.[62] In this context, the Māru-Gurjara style becomes representative of all of these religions and of India as a whole.

An examination of the spread and continuity of the Māru-Gurjara style provides fertile ground for rethinking the routes and movement of Jaina architectural and spatial forms. More important than the independent migration of craftsmen, seem to have been the movement of Jaina merchant families and their conceptual and emotional link with this style. The creation of a demand and a market for a Māru-Gurjara continuation style in other areas of India and abroad has initiated the passage of artists across regional borders and the shipment of their carvings to other continents. Consequently, we are not dealing with an accidental diffusion. The situation outlined here shows a deliberate circulation of architectural forms and a selective reproduction of motives and spatial paradigms through a conscious commissioning of craftsmen reproducing a historic style filled with strong aesthetic, religious, and political associations.

Author’s Note: The material in this paper was first presented at a panel called “Mobile Merchants, Temple Communities, and the Transmission of Architectural Knowledge in Medieval India” during the fifteenth conference of the American Council of Southern Asian Art (ACSAA) in Minneapolis in September 2011. I thank the German Research Foundation (DFG), which has supported my research on Jaina temple architecture in India through its Emmy Noether-Programme since 2002. I am grateful to the Chandaria family in London and their relatives in East Africa for allowing me to reproduce figures 21a, 21b, and 22. Figures 23 and 24 are reproduced with gratitude to Verena Bodenstein. All other photographs in this chapter are by the author.

Notes

Julia A. B. Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture in India: The Development of a Distinct Language in Space and Ritual, in Monographien zur indischen Archäologie, Kunst und Philologie, vol. 19 (Berlin: Herausgeber Stiftung Ernst Waldschmidt, G+H-Verlag, 2009).

This is argued in detail in a colonial and a modern context in Julia A. B. Hegewald, “Building Citizenship: The Agency of Public Buildings and Urban Planning in the Making of the Indian Citizen,” in Citizenship and the Flow of Ideas in the Era of Globalization: Structure, Agency, and Power, ed. Subrata K. Mitra (New Delhi: Samskriti Publishers, 2012), 291–337.

Traditionally, the term “Solaṅkī style” has been used in the literature. See, for example, M. A. Dhaky, “The Chronology of the Solaṅkī Temples of Gujarat,” Madhya Pradesh Itihas Parishad, vol. 3 (1961), 1–83; James C. Harle, The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Pelican History of Art (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986), 239); George Michell, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume I: Buddhist, Jain and Hindu (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 263; George Michell, Hindu Art and Architecture (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 98–102); T. Richard Blurton, Hindu Art (London: British Museum Press, 1992), 196–97); and Susan L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India (1985; repr. New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1993), 483–98. Nowadays, however, in the attempt to avoid dynastic terms, the expression “Māru-Gurjara style” is usually preferred by art historians. This change in terminology appears to have been suggested first by A. Ghosh during a symposium in Delhi in 1967; see Pramod Chandra “The Study of Indian Tempe Architecture,” in Studies in Indian Temple Architecture, ed. Pramod Chandra (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1975), 36. Both spellings—Māru-Gurjara and Maru-Gurjara—exist in the literature. For the first spelling, see M. A. Dhaky, “The Jaina Architecture and Iconography in the Vāstu-Śāstras of Western India” and “The Western Indian Jaina Temple,” in Aspects of Jaina Art and Architecture, ed. U. P. Shah and M. A. Dhaky (Ahmedabad: Gujarat State Committee for the Celebration of 2500th Anniversary of Bhagvān Mahāvīra Nirvāṇa, L. D. Institute of Indology, 1975), 13, 325; M. A. Dhaky, “The Genesis and Development of Māru-Gurjara Temple Architecture,” in Studies in Indian Temple Architecture, ed. Pramod Chandra (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1975), 114. For the second spelling, see M. A. Dhaky, Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: North India—Beginnings of Medieval Idiom (c. A.D. 900–1000)(New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies and Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1998), 283. In actual fact, one should differentiate between three phases: the Mahā-Gurjara style (circa 945 to circa 970) was followed by the Mahā-Maru style (circa 970 to end of century), which then turned into the Māru/Maru-Gurjara style; Dhaky, “Genesis and Development,” 146–64, and Dhaky, Indian Temple Architecture, 283. On the other hand, when referring to the fully fledged northwestern Indian temple style, as a rule, the term Māru/Maru-Gurjara is used; M. A. Dhaky and U. S. Moorti, The Temples in Kumbhāriyā (New Delhi and Ahmedabad: American Institute of Indian Studies and L. D. Institute of Indology, 2001), 43. Interestingly, Solaṅkī style is the term usually employed by Jainas in India and abroad.

The “northwestern style” or “northwestern India” refers to the area roughly covered by the modern states of Rajasthan and Gujarat.

There is a lot of controversy about the precise dates of Mahāvīra’s life, which is placed either around 549–477 BCE or 472–400 BCE (Dhaky and Moorti, Temples in Kumbhāriyā, 3), or possibly even later (Paul Dundas, The Jains, Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices [London and New York: Routlege, 1992], 21–22, 24).

The region was affected by three major Islamic incursions. The first was headed by Maḥmūd of Ghazna in 1025; the second by Sultān Ḳuṭub al-Dīn Aybak in 1197; and the third by Sultān Alāu’d-Dīn Ḵẖaljī of Delhi in 1298; Dhaky, Indian Temple Architecture, 282.

In addition to the Gujarati spelling “Caulukya,” one also encounters the more Sanscritic version “Cāḷukya.” The Rājput clan of the Solaṅkīs of Gujarat ruled from about 950 to 1304, although alternative dates of 961 till 1244 have been suggested (Huntington, Art of Ancient India, 483), depending on whether one views the Vāghelās as a continuation of the Solaṅkīs or their successors.

Kīrttimukha means “face of glory.” It describes a fearful masque or face, usually represented without a lower jaw and often reproduced above doorways and windows and behind statues. The motif generally has been seen as a symbol of the passing of time.

Because of their beauty and intricate nature, ceilings of this kind have been removed from destroyed Jaina temples and inserted in new structures. Particularly well known are those found in early Islamic mosques at Delhi and Ajmer. On this subject, see J. M. Nanavati and M. A. Dhaky, “The Ceilings in the Temples of Gujarat,” special issue, Bulletin of the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery, vols. 16−17 ( Department of Archaeology, Government of Gujarat, Baroda, 1963).

An alternative spelling for padma-śila is padma-śilā (see, e.g., Krishna Deva, “West India: Chalukya Temples,” part 5: “Monuments & Sculpture A.D. 1000 to 1300,” in Jaina Art and Architecture, vol. 2, ed. A. Ghosh (New Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith, 1975), 301. Precursors of ceilings with lotus designs can be seen in the early Jaina rock-cut temples dating from the beginning of the ninth century CE, for example, in Ellora.

For further information on the vidyā-devīs or mahā-vidyās and their positioning on carved struts in the domed ceilings of Jaina temples, see Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 108–10.

Meghanāda-maṇḍapa means “thunder hall” or “echoing hall.” It is striking that vāstu- or śilpa-śāstra texts from the Solaṅkī period make no direct reference to a maṇḍapa of this name. This may be due to the relatively late introduction of this type of hall. There are fifteenth-century textual references to halls bearing this name. See Dhaky, Western Indian Jaina, 382, 352.

In the Mahāvīra temple at Ghanerao, founded in the mid-tenth century, a slightly detached raṅga-maṇḍapa was added at a later stage. A similar case can be found in the Mahāvīra temple at Osian; there, however, the detached open hall was set much farther apart from the original temple structure.

The earliest preserved example of such a toraṇa gate, dated by an inscription to 1018, is in the compound of the Mahāvīra temple at Osian. Similar structures, dated to the middle of the eleventh and the middle of the twelfth centuries respectively, have been preserved in the contexts of the Jaina temple at Lodruva in Rajasthan and the Ādinātha temple at Vadnagar in Gujarat. While it is typical for temples built during the reign of the Solaṅkī rulers to have freestanding gateway structures, most gateways in other Jaina temples are associated with protective compound walls and gates. Although the detached Māru-Gurjara toraṇas do not protect temples from the outside, they emphasize the idea of the threshold.

The Vāstu-śāstra (circa late eleventh century) and the Vāstu-vidhyā of Viśvakarmā (circa early twelfth century)—both Māru-Gurjara vāstu texts dating from the time of the Solaṅkī rulers—describe and provide essential information on the positioning and proportions of chains of subsidiary shrines. Further information on these texts is provided by Dhaky, Western Indian Jaina; Prabhashankar O. Sompura and M. A. Dhaky, “The Jaina Architecture and Iconography in the Vāstusāstras of Western India,” in Aspects of Jaina Art and Architecture, ed. U. P. Shah and M. A. Dhaky (Ahmedabad: Gujarat State Committee for the Celebration of 2500th Anniversary of Bhagvān Mahāvīra Nirvāṇa and Nivajivan Press), 13−20; and Shantilal Nagar, Iconography of Jaina Deities, 2 vols. (Delhi: B. R. Publishing Corporation, 1999).

Mount Ābū is known locally as Ābū Parvata, meaning the hill or mountain of Ābū.

Vimala is also referred to as Daṇḍādhina Vimala. The Ādinātha temple was constructed in VS 1088, converted to either 1031 CE or 1032 CE. See the relevant sections in Asim Kumar Chatterjee, A Comprehensive History of Jainism, vol. 2, AD 1000−1600 (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2000), 2; Harihar Singh, Jaina Temples of Western India, Parshvanath Vidyashram Series 26 (Varanasi: Parshvanath Vidyashram Research Institute, 1982), 186; and Michell, Monuments of India, 274. In addition, Mount Ābū is known as Dilvara (Delvāṛā or Dilvāḍā), a corruption of the words deul (temple) and vāṛā (locality, ward), consequently meaning “place of temples” or “temple city”; D. R. Bhandarkar, “III: Some Temples on Mount Abu,” Rupam: An Illustrated Quarterly Journal of Oriental Art, no. 3 (1920), 14.

In Gujarat, prominent religious buildings in all major cities were raided and destroyed in the attacks of 1024–26, 1217, 1297, and 1304. See Bhandarkar , “Some Temples,” 12; Dhaky and Moorti, Temples in Kumbhāriyā, 13.

For information on specific rulers and their achievements, see Chatterjee, History of Jainism, vol. 2, 30–38.

Kumārapāla remained a devout Hindu but in his later years actively supported the spread of Jainism. Some historians argue that he converted to Jainism and that he aimed to create a model Jaina kingdom; Ganesh Lalwani, Jainism in India (Jaipur: Prakrit Bharati Academy, 1997), 69–70; John Cort, “Who Is a King? Jain Narratives of Kingship in Medieval Western India,” in Open Boundaries: Jaina Communities and Culture in Indian History, ed. John Cort, Sri Garib Dass Oriental Series, no. 250 (Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications, Indian Book Centre, 1998), pp. 85–110; Chatterjee, History of Jainism, vol. 2, 11–12; Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 221.

According to the chronicler Merutuṅga, Kumārapāla erected as many as 1,440 temples throughout India; Lalwani, Jainism in India, 71.

Other temples might have collapsed due to technical and structural problems and imperfections. Huntington (Art of Ancient India, 483) also points out that marble temples were destroyed as the marble could be calcined into lime.

Besides building temples, Kumārapāla is renowned for having cut steps into the rock at Junagadh to improve the pilgrimage route up the sacred hill of Mount Girnār; Dhaky and Moorti, Temples in Kumbhāriyā, 19.

For further details on these allegations, see Chatterjee, History of Jainism, vol. 2, 19, and Singh, Jaina Temples, 44.

Information on these temples can be found in Deva, “West India: Chalukya Temples,” 304–5, and Dhaky and Moorti, Temples in Kumbhāriyā, 20.

The Neminātha temple is alternatively known as the Lūṇa-vasahī, and the Mallinātha temple variably as the Vastupāla-Tejapāla temple or the Vastupāla-vihara.

In addition, the Jaina merchant Jagaḍu is known as Jagaḍuśā or Jagaḍū Śāha.

For additional information, refer to Chatterjee, History of Jainism, vol. 2, 28–29, 38–40, and M. C. Joshi, “Monuments & Sculpture A. D. 1300 to 1800: North India,” in Jaina Art and Architecture, vol. 2, published on the occasion of the 2500th Nirvana anniversary of Tirthankara Mahavira (New Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith, 1975), 343.

This issue is discussed in Joshi, “Monuments & Sculpture,” 339, and Lalwani, Jainism in India, 59, 75.

Various spellings are in use for the term tunk, a fortified temple compound. This article uses the most common Hindi spelling, tunk. However, the term is also regularly spelled tuk, tuṅg, ṭuk, ṭuṅk, or ṭoṅk.

The question of the concept of the golden age in Asian art has been analyzed in detail; see Julia A. B. Hegewald, ed., In the Shadow of the Golden Age: Art and Identity from Gandhara to the Modern Age, Studies in Asian Art and Culture (SAAC), vol. 1 (Berlin: EB-Verlag, Berlin, 2014), especially “Introduction: Out of the Shadow of the Golden Age,” pp. 31–76. In a Jaina context, this idea also has been closely linked to the Hoysaḷa dynasty and its associated aesthetic style in Karnataka, ranging roughly from the eleventh to thirteenth century; Julia A. B. Hegewald, “Golden Age or Kali-Yuga: The Changing Fortunes of Jaina Art and Identity in Karnataka,” In the Shadow of the Golden Age, 311–46.

For a detailed analysis of the rebuilding activities on Mount Śatruñjaya, see Hawon Ku, “Temples and Patrons: The Nineteenth-Century Temple of Motśāh at Śatruñjaya,” International Journal of Jaina Studies 7, no. 2 (2011), 1–22 and her, unfortunately, unpublished PhD dissertation “Re-formation of Identity: The 19th-century Jain Pilgrimage Site of Shatrunjaya, Gujarat” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2007), 287.

Definitions and descriptions of these reasonably modern temple types can be found in Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 142–44.

A severe drought affecting the east of India is believed to have led to the migration of large numbers of Jainas away from the region in the third century BCE. In the first centuries CE, interreligious conflict decimated the strength of the community even further, causing again mass migration and leaving a very rudimentary presence in the area from about the third century CE; Maruti Nandan Prasad Tiwary, History of Jainism in Bihar (Gurgaon: Academic Press, 1996), 186. The remaining Jainas were further reduced in numbers between the seventh and thirteenth centuries through incursions of warring factions from the South, the introduction of Islam in the region, the removal of royal patronage, and the cessation of trade connections; Tiwary, History of Jainism, 14–179, 187. A pronounced trend back to the East is noticeable only from the sixteenth century onward. Those Jainas who “returned” to eastern India appear to have been primarily members of the influential western Indian trading families who also migrated to other areas of the subcontinent during the Mughal period.

Śvetāmbara Jainas consider Vaishali the birthplace of Mahāvīra, while Digambara Jainas believe this event to have taken place at Kundalpur, located in the same state.

Alternatively, the Dādā Bāṛī Jaina temple complex is also known as the Dādā Baṛā.

The precise date of completion of the temple, noted down on the building itself, is Samvat 1992.

A detailed description of the layout of Jaina temples following the maṇḍapa-line principle can be found in Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 140–41.

The open hall, inserted between the closed hall and the porch, is only one pillar deep and, as such, more part of an extended porch than a proper hall, where devotees can conduct rituals or assemble for communal veneration. In this temple, these additional functions must be accommodated by the larger closed halls. This layout is relatively common in modern temple constructions. A further example, following the same principle—although two side porches have been added—is the Pāraṇā Evam Kalyāṇaka temple at Hastinapur.

The dādā-gurus or dādā-guru-devas are the four sanctified medieval teachers of the Śvetāmbara Kharatara Gaccha. Today, the term can be used more generally for any deceased revered teacher of the Jaina faith. For more details on the dādā-gurus, see Lawrence A. Babb, Ascetics and Kings in a Jain Ritual Culture, Lala S. L. Jain Research Series (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1998), 111–26.

He is one of the Kharatara Gaccha’s four sanctified medieval teachers (dādā-gurus).

It is also common throughout the region to find lotus designs painted onto the domical ceilings of halls. Two clear examples are the Śrī Cintāmaṇī Pārśvanātha Śvetāmbara temple at Hastinapur and the Dharmanātha temple at Ronahi.

It is interesting to note that despite the strong western Indian undertones, the highly stylized and mass-produced-looking sculptures adorning the outer sides of the temple are more akin to Chandella sculptural temple decorations than to those in the Māru-Gurjara style. As a result, the temple represents a relatively low-quality replica of a blend of well-known and highly rated artistic styles.

These Pārśvanātha images make reference to particularly sacred statues at Ludrava and Shankeshvar, small towns in Rajasthan and Gujarat respectively. See, for instance, the Śrī Ludrava Pārśvanātha Jina Mandir in Sholapur, Maharashtra, which was started by the Śvetāmbara community in 1993.

The cult of Nākoḍā Bhairava originates in a small village near Jodhpur in Rajasthan. Images of this manifestation are, for instance, displayed in the Śvetāmbara Jaina temple in Margaon in Goa. Figural representations of this kṣetra-pāla are only portrayed from the head down to the waste, and seem to emerge from a pedestal below; Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 100–104. See also the study by Knut Aukland, “Understanding Possession in Jainism: A Study of Oracular Possession in Nakoda,” Modern Asian Studies, 47 (2013), 109–34. The veneration of icons connected with a specific sacred place of Śvetāmbara worship in Rajasthan or Gujarat can be associated with the Śvetāmbara community throughout India and abroad.

For a discussion of Jaina temple architecture in central India, see Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 395–473.

The large Ādinātha temple at Kulpak reproduces all the hallmarks of the medieval northwestern Indian style. It has a large raṅga-maṇḍapa with a lotus ceiling (but a square rather than an octagonal pillar arrangement), a second shallow open hall, front and side porches with elaborate ceiling panels, multi-lobed cusped flying arches, highly ornate pillars and beams, and buff-colored sandstone as a building material. Only the outside moldings of the temple are less elaborate than those found in the Northwest, and there are no external figural representations. A clearly South Indian feature, which has been combined with predominantly Māru-Gurjara features, is the Drāviḍa temple tower (vimāna) above the triple-sanctuaries.

The Vāsupūjyasvāmī temple in Madras is a hybrid construction. It combines elements from the domestic house-type, hall-type, and maṇḍapa-line Jaina temples and has been constructed on two superimposed levels. It is a white marble temple with large numbers of flying arches, profuse ornamentation, and carved lotus ceilings.

On domestic house-type Jaina temples, see Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 144.

The Jaina temple in Leicester was the first consecrated Jaina temple in the Western world; see University of Leicester webpage, www2.le.ac.uk/departments/archaeology/research/projects/mapping-faith/faith-trail/jain-centre, accessed on November 13, 2013. Banks has studied the migration of Jainas to Leicester; see Markus Banks, Organizing Jainism in India and England, Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

The marble, which unusually is yellow-brown in color, was carved in India and shipped to the United Kingdom.

For instance, the first Jaina followers arrived in Leicester in the UK from India, from Kenya and later from Uganda as well. The European Jaina community, the Jain Samaj Europe, was founded in Leicester in 1973; see University of Leicester webpage.

A samavasaraṇa is the preaching hall of a Jina, built by the gods to house divinities, men, and animals to listen to the first formalized teaching that a Jina delivers after attaining his enlightenment.

An alternative spelling for the name of this temple is Old Caubārā Ḍerā.

For a discussion of northwestern Indian vāstu- or śilpa-śāstra texts, see Dhaky, “The Jaina Architecture and Iconography,” 13–19; Dhaky, “Western Indian Jaina Temple,” 125–27, and Hegewald, Jaina Temple Architecture, 151.

Other factors that further increased the popularity of the Māru-Gurjara style include the widely noticed reconstruction of the Somanātha temple in Patan (Prabhāsa) in Gujarat (Richard H. Davis, “Reconstructions of Somanātha,” Lives of Indian Images [Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1997], 186–221) and the influence of architects from the Sompura community, such as Prabhashankar O. Sompura (Sompura and Dhaky, “Jaina Architecture and Iconography”), who in a variety of modern śilpa-śāstra texts and their building practice encourage an idealization of the Māru-Gurjara aesthetic. These additional areas merit a closer examination in the future.

See, for instance, the Hindu-Jaina temple in London, Ontario, Canada, which is largely Hindu but also houses a statue of Mahāvīra; or the Gītā Bhavan Hindu temple in Manchester, which also contains statues of the Sikh gurus.

Ars Orientalis Volume 45

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.