- Volume 45 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.7mb

Abstract

This essay examines the ways in which travel routes facilitated the transmission of architectural knowledge across central India, not only in major urban centers but also in remote rural places. It focuses on Kadwāhā, a village in Madhya Pradesh, which emerged as a major temple town during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. As a group, Kadwāhā’s temples reveal a heterogeneity of architectural and sculptural forms that speaks to its status as a key stopping point on the road between Narwar and Chanderī. This essay highlights three ways in which artistic ideas may have been transmitted across vast geographic distances. First, it examines categories of mode and style, traceable through plans and elevations, which likely point to decisions made by architects and patrons. Second, it shows how sculptors experimented with and transformed ornamental and iconographic features brought from other regions. Third, it turns to religious iconography as a way of mapping the movement of religious practitioners.

Introduction

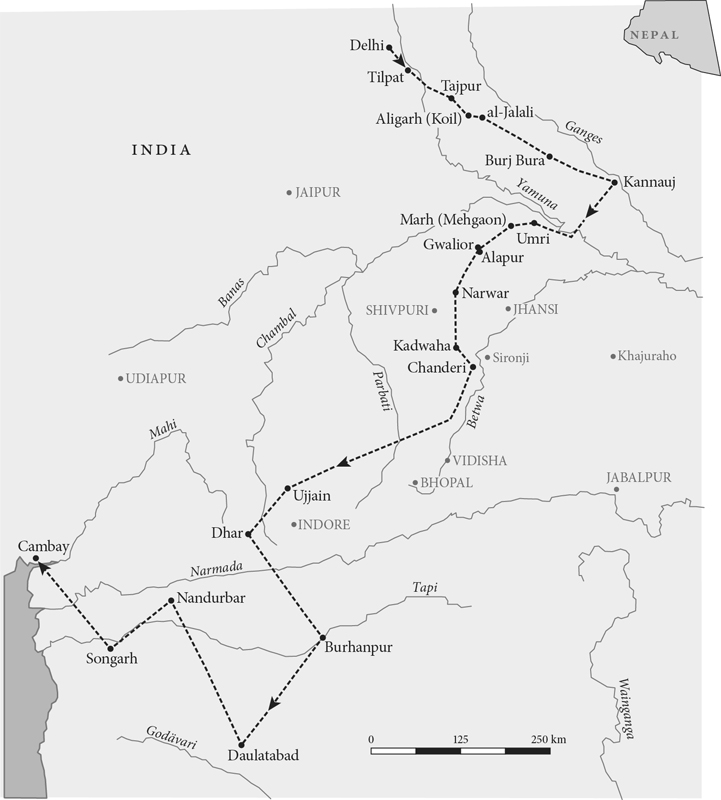

In 1342, Sultan Muhammad Tughluq appointed Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, the famed Moroccan traveler who had taken up residence in Delhi, as ambassador to the Mongol court in China.[1] He was tasked with accompanying a group of Chinese emissaries back home and conveying gifts of slaves, fine cloths, musk, and swords to their emperor. The party moved southeast from Delhi toward Aligarh (Koil) and Kannauj, and then southwest through Gwalior (Gopādri) and Chanderī to Ujjain and Dhār, and across the Narmada River to Daulatabad. From there they went through Mālavā, stopping at Dhār before finally arriving at Cambay, where they met the boat that took them around the coast of southern India and eastward to China (fig. 1). The route was arduous and fraught with danger—as evidenced by Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s distinctly embellished account of being pursued and kidnapped by groups of Hindu mercenaries along the way—but it was also well established and frequently traveled. A matter of just over a thousand miles, it could be traversed in a matter of three to four months.[2]

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s travels through India are extremely well known to scholars, and his Riḥla (Travelogue) has been mined heavily, both as a source of social and economic history and as an indicator of larger, increasingly global routes of trade and cultural exchange.[3] The caravan of luxury goods with which he traveled is emblematic of the movement of objects and ideas. At various stops throughout his extended journey, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, like many travelers who preceded and followed him, recorded details of local flora and fauna as well as his conversations with the people he encountered. While much scholarly attention has been given to his descriptions of life in major cities (such as Delhi, Daulatabad, and Cambay) and of significant regional fortresses (such as Gwalior, Aligarh, and Chanderī), what makes this particular leg of his travels so important is that it took him to far more obscure places. In the process of journeying from Delhi to Cambay, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa stopped at crucial locations in rural central India. Although they were connected to larger administrative centers, these places were small enough to escape mention in many chronicles and imperial records from precolonial eras.[4]

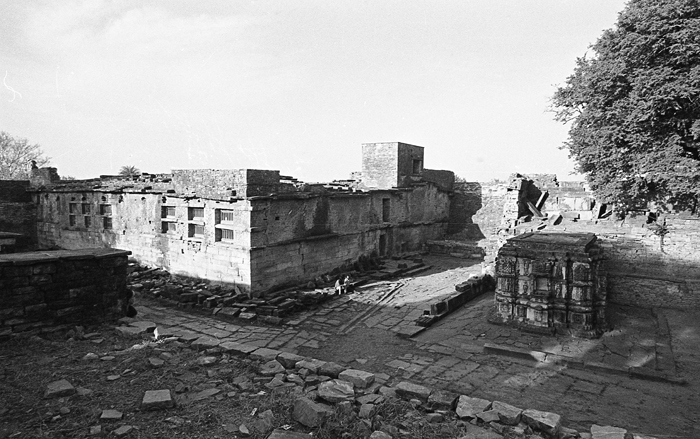

A good case in point is the place referred to as Kajarrā or Kajwarā.[5] Although Kajarrā is popularly understood today as the famous temple town of Khajurāho, this is unlikely to have been the case. Khajurāho was neither a site of great importance during Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s time nor a particularly convenient stop on his journey. Instead, Kajarrā was more likely a village known today as Kadwāhā, referred to locally as Kadwāyā. Not only did it lie directly along Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s route, but in the 1340s, it also was a frontier outpost of the Tughluq sultanate and home to a fully functional Islamic ribāṭ (frontier outpost), which fell within the Tughluq domains (figs. 2–3).[6] That Kadwāhā was likely Kajarrā (or Kajwarā) is further supported by the Mughal emperor Bābur’s (1483–1530) account of his conquest of the fortress at Chanderī in 1527–28, as described in the Bāburnāma (Bābur’s memoirs). Kadwāhā, which Babur knew as Kachwaha (or Kachwa), was Babur’s last major stop before arriving at Chanderī.[7]

Key: (a) Śaiva maṭha, circa 10th century; (b) Platform with miḥrab, circa 14th century; (c) Śiva temple, circa 10th century CE; (d–e) Remains of stepped well, circa 14th or 15th century; (f) Stepped terrace, circa 1940–41 CE; (g) Dirt and rubble

Taking Kadwāhā as a point of departure, this essay examines the ways in which routes of travel facilitated the transmission of cultural and, more specifically, architectural knowledge across far-ranging distances, not only to major urban centers but also to deeply remote places. Situated between Narwar and Chanderī, Kadwāhā lay directly along a major route that followed the path of key rivers that flowed northward from just above the Narmadā River valley into the Yamunā River basin (fig. 1). This route, although not widely acknowledged, connected northern imperial and regional capitals with central India and the Deccan.[8] The geographic location, a place that was less central than in-between, likely gave rise to Kadwāhā’s first existence many centuries before the writings of travelers such as Ibn Baṭṭūṭa and Bābur provided written confirmation of its connection to wider routes.

Between the ninth and early eleventh centuries, Kadwāhā grew from a humble settlement into a monumental temple town that contained no fewer than fifteen temples, a monastery, and a range of wells, gardens, and water tanks. These formed the foundation for the later medieval town that grew around a thirteenth-century fortress, built to encompass a monastery at the settlement’s center. In the fourteenth century, the fortress was converted into a fully functional ribāṭ, which contained residential structures, a large stepped well, and a mosque.[9] Although references to Kadwāhā do not appear in chronicles or traveler’s accounts for earlier periods, the village’s material record suggests that its very formation was connected to its geographic position along similar north–south routes of travel that connected earlier political centers such as Gwalior, Kannauj, and Buḍhi Chanderī (Old Chanderī) to points further south.

This essay moves in the following order. First, I turn briefly to issues of geography and history to situate Kadwāhā within broader transregional, regional, and local contexts in the centuries leading up to the first millennium. Then I highlight three distinct ways in which the transmission of knowledge can be traced through Kadwāhā’s temples. The first is through temple modes and styles, seen through plans and elevations, which may reveal the hand of distinct local and regional patrons in the shaping of a new architectural environment. The second looks to the engagement with newly introduced ornamental forms through the agency of local artists. The third turns to religious iconography as a way of mapping the movement of religious practitioners. Each of these represents a categorically distinct set of architectural features that circulated among different social groups with access to varying types of knowledge.

Geography, History, and Routes of Travel

Today, Kadwāhā is a relatively remote village of approximately eight hundred households and 4,500 people.[10] Nonetheless, it remains the nexus of the surrounding area: the modern Bījāsan Devī temple attracts crowds of villagers and merchants to Kadwāhā to worship and exchange goods at a biweekly festival.[11] Close by is a gaḍhī (fort) that contains the remains of the earlier maṭha (monastery), its temple, and the mosque that was built when the fortress was converted into a ribāṭ. The gaḍhī and the monuments that preceded and followed it form the heart of Kadwāhā’s current residential core, whose much earlier roots are still visible through fragments of medieval town walls.[12] As the oldest structure within the village center, the maṭha seems to have been the stimulus for the larger settlement, whose boundaries are marked by the circular distribution of Kadwāhā’s temples to the north, east, and west (fig. 4).

The remaining fourteen temples within Kadwāhā proper are clustered in distinct groups that radiate around the monastery and frame the outskirts of the village. The earliest of these, the late ninth-century Caṇḍāla Maṭh, is situated to the northwest (fig. 5). Just west of the monastery and the gaḍhī are four temples: the solitary Eklāvālā temple and the three temples of the Akhatiavāla group (figs. 6–7). Five more temples—including one known today as the Mārgatvāla temple, and four more set off in pairs that form the Nahalvār and Khirnīvālā groups—can be found to the north (fig. 8). And finally to the east are two more pairs of temples, constituting the Pachalīvālā and Morāyat groups, the latter of which contains the grand Toteśvara Mahādeva, perhaps the best known of Kadwāhā’s shrines (fig. 9). With the exception of the Caṇḍāla Maṭh and the eleventh-century Toteśvara Mahādeva and Mārgatvāla, Kadwāhā’s temples generally can be dated to the tenth century on the basis of style.[13] The maṭha itself most likely dates to the ninth or tenth century and the accompanying temple to the first half of the tenth. The centrality of the maṭha and its temple is emphasized through two factors. The first is their later incorporation into a thirteenth-century fortress built as a response to Sultanate-era incursions in the area under the Khaljis (circa 1290–1316).[14] The second can be seen in the distribution and affiliations of the surviving temples throughout the village; while ten are either Śaiva or Śaiva-śakta, only five are Vaiṣṇava.

Historically, Kadwāhā and its broader subregion were fairly remote, situated within what R. N. Misra has described as the geography of the wilderness (āraṇya) beyond the domain of established villages (grāma) and earlier historical states (janapadas). The area may have been populated by a range of itinerant communities, including autonomous tribal groups (āṭavikas), ascetics, and merchants.[15] Nonetheless, it was central in its own way. Situated in the southernmost part of the ancient region of Gopakṣetra, it sat between at least three other regions—Jejākabhukti (Bundelkhand) to the east, Dāśārṇa to the south, and Mālavā to the west (fig. 10).[16] More specifically, it developed along an area sometimes referred to as the Mahuār River region, which formed between the branching ends of two local rivers, the Madhumatī (Mahuār) and Ahīrāvati, which found their source eighty to ninety kilometers north in the Sindhu River.

The Madhumatī and Ahīrāvati Rivers, although never major waterways, were advantageous because of their geographical relationship to the Betwā River, which ran roughly parallel to the Sindhu in a winding journey along the Yamunā basin.[17] Along the way, each river passed important regional centers—Vidiśa in the case of the Betwā, and Gwalior and Padmāvatī (modern Pawāyā) in the case of the Sindhu. Flowing steeply southward, the Mahuār and Ahīrāvati were ideally situated to facilitate the development of settlements between the Betwā and the Sindhu. Thus, travelers seeking passage to Gwalior from Vidiśa, Devgaḍh (Deogarh), or any number of important places located along the Betwā River, may have found sites such as Kadwāhā to be ideal points of transition from which they could then continue their journey to the next key junction.[18] Kadwāhā may have grown in importance because of its proximity to a westward bend in the Betwā River that marked a transition to the tributaries of the Sindhu. Near the confluence of the Mahuār and Sindhu Rivers was Padmāvatī, an old urban center that had flourished under the Nāga kings who had ruled areas of central India prior to their conquest by the imperial Guptas in the fifth century.[19]

During the seventh and eighth centuries, the areas around Kadwāhā became integrated, to varying degrees, into the administration of the various rulers of Kannauj (Kānyakubja), situated in the Gaṅgā-Yamunā Doab to the north, and Ujjain, in Mālavā, to the west. That the long-distance connection with imperial Kānyakubja stems back at least to the seventh century is attested through an inscription describing the construction of a Śiva temple at Mahuā by a local king named Vatsarāja.[20] While Vatsarāja may have hailed from somewhere near Ujjain, the poet who composed the inscription is believed to have had some connection with the imperial center. In the inscription, he is described as Bhaṭṭa Īśāna, son of Bhaṭṭa Somāṅka and younger brother of Bhaṭṭa Devasvāmin, who hailed from Kānyakubja.[21] Evidence from Padmāvatī, further to the north, reveals continuing transregional connections, moving north to south, from the Deccan to Kānyakubja, as seen through the movements of the eighth-century court poet, Bhavabhūti. Originally from Vidarbha, a city that once stood less than fifty miles from modern Nagpur in Maharashtra, Bhavabhūti lived in Padmāvatī for a time before taking up a post at the court of the imperial monarch Yaśovarman of Kānyakubja (Kanauj) (circa 720–50 CE).[22] Bhavabhūti himself likely passed through the Mahuār River region on the way to Padmāvatī, mirroring the imagined journey of a yoginī named Saudāminī, which he evoked beautifully in his renowned drama, the Mālatī-Mādhava.[23]

In the early ninth century, Kānyakubja was captured and occupied by the imperial Gurjara Pratīhāras, who remained the dominant power in northern and central India through the middle of the tenth century. In the areas around the Mahuār (Madhumatī) and Ahīrāvati Rivers, the Pratīhāra presence was loosely felt due to the actions of their local feudatory lords (mahāsāmantādhipatis), who operated under the jurisdiction of the Gurjara Pratīhāras’ agents in Gwalior. These connections can be seen particularly in a memorial pillar inscription from Terāhī, a site less than ten miles northeast of Kadwāhā, dated to VS 962 (905 CE), commissioned upon the death of a chief named Allabhaṭṭa during a battle against the Karṇāṭas or the Rāṣṭrakūtas of Maharashtra.[24] Although Allabhaṭṭa’s identity remains a matter of conjecture, R. N. Misra has previously suggested that he hailed from Gwalior and may have been an individual named Alla, son of Vāillabhaṭṭa. Alla was appointed as the guardian of the fortress at Gwalior and served as the “chief of the boundaries” (maryādādhurya) under the Gurjara Pratīhāra king Bhojadeva.[25] It may be that the recorded battle was related to the successful military campaign of the Gurjara Pratīhāra king Mahendrapāla (reigned 885–910) along the Gulf of Cambay in Gujarat.

Although connected across wide geographies, the long distance even from Gwalior may have lent local lords a greater degree of autonomy than was the case in places closer to the administrative center, as is suggested in two more memorial pillar inscriptions, also from Terāhī. Dated just two years earlier, to VS 960 (903 CE), these inscriptions record warriors who fell in what appears to have been a local battle, perhaps over territory, between two mahāsāmantādhipatis named Guṇarāja and Undabhaṭṭa on July 16 of that year.[26] Ongoing conflicts with the Rāṣṭrakūtas over Madhyadeśa may have hastened the transformation of feudatory chiefs into significant and autonomous local royal rulers. During the transition, Undabhaṭṭa’s family took on a new level of authority from their capital at Buḍhi Chanderī. This process, which can be traced through inscriptional records of the tenth and early eleventh centuries, is attested with particular clarity in an extended inscription from the site of Siyaḍoṇī (modern Sīron Khurd).[27] Undabhaṭṭa is listed as one of a number of individuals who provided endowments for daily payment to the local Viṣṇu temple during VS 964 (907–8 CE), just a few years later than the record from Terāhī, which was located only twenty-seven miles away. He is described by the titles mahāsāmantādhipati, mahāprātihāra (superintendent or guard of a capital city), and samadhigatāśeṣamahāśabda (feudatory). But because the inscription from Siyaḍoṇī contains an extensive record of numerous deeds covering a sixty-five-year period, from VS 960 to VS 1025 (903–4 to 968–69 CE), it reveals a longer history through which Undabhaṭṭa’s successors claimed increasing power by utilizing more prestigious imperial titles. By the end of the tenth century, the king Harirāja had fully transitioned from mahāsāmantādhipati to mahārājādhirāja and nr̥pacakravarttī, or “emperor among kings.”[28]

This transformation from local feudatory chief to autonomous royal ruler culminated in a fragmentary inscription found in the remains of the maṭha in the center of the gaḍhi at Kadwāhā.[29] According to the inscription, King Harirāja traveled to Kadwāhā seeking dīkśa (initiation) from the Śaiva sage presiding over the maṭha. Before the guru performed the ritual, he asked the head attendant, “Who is this long-lived king [nr̥pa]?” The attendant replied by identifying Harirāja as a member of “a gotra of the Pratīhāra kings [mahīśvara],” which stemmed from a ruler named Durbhaṭa “... whose lotus feet were attached to the circle of the crest jewels of ... [the] fierce cloud of the roaring Gūrjjaras....”[30] This reference is quite telling, as his predecessor Undabhaṭṭa functioned as the mahāsāmantādhipati of the imperial Gurjara Pratīhāras, who are referred to by the title parameśvara (supreme lord) in the Siyaḍoṇī inscription.[31] The ascendency of this local family, from mahāsāmantādhipati to parameśvara, belies the predominant scholarly belief that Kadwāhā and other sites in its vicinity fell under the suzerainty of the Kacchapaghātas, who ruled further north at Gwalior and Sihoniyā during the tenth and eleventh centuries and are notably absent from the inscriptional record. By contrast, at least five fragmentary inscriptions related to the Pratīhāras of Buḍhi Chanderī were found at Kadwāhā,.[32]

The shifting nature of politics left their mark more clearly in the architectural than in the inscriptional record. During the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries, the Mahuār River region gave rise to a number of new settlements, recognizable through the presence of intact stone temples and monasteries in the modern villages of Mahuā, Indor, Sakarra, Ranod, Terāhī, Surwāyā, and Baktar (figs. 11–12).[33] In addition to marking the development of new settlements, these temples also suggest a new degree of permanence, not merely of local agrarian communities but of religious groups that may have been more frequently itinerant in earlier periods. While the buildup of new monuments occurred slowly during the seventh through ninth centuries, the tenth and eleventh centuries witnessed more rapid developments, most visible through the expansion of earlier monasteries and the rise of new temple towns, such as Kadwāhā and Thubon. Such architectural activity, particularly in the long-lasting medium of stone, is fairly significant in relationship to this larger history as it indexed both an influx of wealth and an investment in the local region. For example, the expansion of architectural activities at Kadwāhā was likely linked, in part, to the attention of the newly formed Pratīhāras of Buḍhi Chanderī, the descendants of Undabhaṭṭa, who had served as the mahāsāmantādhipatis under the Gwalior-based agents of the imperial Gurjara Pratīhāras.[34]

At the same time, Kadwāhā cannot be fully understood through the rubric of royalty. At larger centers, such as Khajurāho, the sponsorship of temples was connected to the imperial aspirations of their patrons. Accordingly, one finds a regulated homology of ornamentation, style, and form—as well as a grandeur of scale—that expresses architecture’s potential to articulate power and political authority. In contrast, the temples at Kadwāhā were a truly motley crew. Instead of homology, we encounter a diversity of scale, architectural form, and ornamentation.[35] Rather than signaling a conscious imperial program, we see instead multiple creative and dynamic engagements with architectural ideas and building practices circulating on wider regional and transregional levels. In short, the diversity of the architectural styles and forms points less to the model of a royal center than to the eclecticism of growing new communities settling not at a remote outpost, but a place situated along the borders between well-defined states and regions and along significant routes of travel.

Locating Patrons through Mode and Style

Compared to other sites in southern Gopakṣetra, Kadwāhā boasts a fairly copious epigraphic record, consisting of more than three dozen inscriptions dating between the tenth and sixteenth centuries. However, as noted earlier, most of the records are either very short or fragmentary; they are primarily one-line pilgrim records or brief notes concerning repairs to existing structures or the establishment of gardens and wells. Of the few longer inscriptions that survive, only the one describing Harirāja’s visit to the monastery to request initiation is well preserved, and even that inscription is too broken to be fully deciphered. None of the surviving records constitute a foundation inscription, commissioned to record the construction of a new monument. As a result, it is impossible to ascertain the full range of Kadwāhā’s patrons solely through textual sources. It is likely that the Pratīhāras of Buḍhi Chanderī were involved in some fashion, and they may have been responsible for founding a few of Kadwāhā’s temples. But the monastery too was a factor, as it served as a major branch of a lineage of Śaiva sages known as the Mattamayūras. The ācāryas and gurus who headed Mattamayūra monasteries elsewhere in southern Gopakṣetra took credit for a range of architectural activities, including the construction and renovation of their own monasteries at other sites; the foundation of new temples; and the establishment of gardens, wells, and step wells.[36] In addition, Kadwāhā’s residents were likely partially responsible for the construction of temples.[37]

Although inscriptions are helpful, they are not always needed to decipher questions of patronage and artistic intention; these come out quite powerfully through an analysis of architectural forms. At Kadwāhā, hints of patronage can be discerned from variations in temple styles and modes. In employing the terms mode and style, I follow other scholars in distinguishing between distinct yet overlapping systems affecting the design and appearance of a temple. These act in conjunction with categories of language and idiom. Within the context of medieval India, temples generally can be classified as either as Nāgara or Drāviḍa, most easily recognizable by the curvilinear or horizontally pyramidal stacked superstructures associated with North and South India respectively. As Adam Hardy has recently argued, Nāgara and Drāviḍa are best understood as architectural “languages,” in the sense that each provided a discrete “kit of architectural parts,” or a vocabulary of building forms and elements, that could be assembled in various systematized ways.[38] Within each language emerged a range of distinct “modes,”, characterized by combining elements of an overarching language into clearly recognizable patterns. Other scholars have defined mode in varying fashions. According to Phillip Wagoner, mode also can be understood as a “comprehensive system of articulation for the temple’s exterior, regulating the forms not only of the superstructure but of other levels of the elevation as well, including the walls and plinth.” On a more conceptual level, Ajay Sinha has described mode as a systemic reworking of the conceptual frame of a building.[39] Style, a similarly slippery concept in Indian architecture, can be felt through the application of distinct features—including systems of proportion, the arrangement of imagery, and the treatment of moldings—to monuments, regardless of their overarching mode. While styles often have regional associations, modes are typically transregional but can vary significantly through their expression in distinct regional styles. Variations in regional styles, introduced by local artisans, have been fruitfully termed “idiom” in scholarly discussions, as described in further detail below.[40]

In northern India, the earliest fully developed Nāgara modes included the phāṁsanā (wedge-shaped) and latina (mono-spired). During the course of the tenth and eleventh centuries, architects experimented with the latina formula to produce new modes; in central India, the most prominent were śekharī and bhūmija, characterized through the architects’ experimentation with anekāṇḍaka (compound-spired) forms (figs. 13–14). Although bhūmija and śekharī were transregional in scope, both may have carried political or regional associations. While the bhūmija mode proliferated in Mālavā and in places under the suzerainty of the Paramāra dynasty, the śekharī was preferred by other regional rulers, most notably the Chandellas of Jejākabhukti.[41] Śekharī flourished in the tenth and early eleventh centuries in Khajurāho, where it was fully realized through the implementation of samatala (equal-sided) projections and the systematic replication of both uraḥśr̥ṅgas (embedded Latina spires) in the center and kūṭastambhas (pillars topped by miniature shrine towers) above the subsidiary projections (i.e., the karṇas and pratirathas).

Among the handful of temples still possessing their superstructures at Kadwāhā, we find three Nāgara temples, including one example of a phāṁsanā maṇḍapikā (shrine emulating an open pavilion), and two examples each of latina and śekharī temples. In particular, the appearance of phāṁsanā and śekharī follows a distinct chronology. While the earliest temple at Kadwāhā, the ninth-century Caṇḍāla Maṭh, was built in the phāṁsanā mode, the two latest temples—the early eleventh-century Mārgatvāla and Toteśvara Mahādeva—were built in the śekharī mode (figs. fig. 5, fig. 9). The plans of the remaining ten temples indicate that the latina was generally the preferred mode throughout the tenth century. Such developments suggest that Kadwāhā’s temples followed broader transregional trends across northern and central India. The use of the phāṁsanā for the Caṇḍāla Maṭh resonates with its popularity both across northern and central India in earlier centuries as well as locally with ninth-century maṇḍapikā temples at the nearby sites of Baktar, Mahuā, and Sakarra. The appearance of śekharī just after the turn of the eleventh century, however, followed the increasing popularity of anekāṇḍaka forms across similar transregional lines.[42]

While shifts in modality seem here to indicate the introduction of new approaches to building over time, the application of distinct temple styles may have been deliberate patron choices. Throughout the tenth and eleventh century, all of Kadwāhā’s temples, regardless of their overarching modality, were built following one of two easily distinguishable styles. In plan, both were pañca-ratha (five-part), meaning that they all possessed the same five projections on each cardinal wall. However, they differed significantly in the distribution of salilāntaras (recesses) applied between the primary projections along the main portion of the temple wall.[43] In the first group, salilāntaras were inserted between the karṇas (corners) and pratirathas (intermediary projections), but not between the pratirathas and bhadras (central projections) (figs. fig. 8, 15,16). In the second group, salilāntaras were applied between every projection of the wall, a choice that fundamentally changed both the appearance of the wall and the possibilities for the sculptural program (figs. 6–8, 17).[44] In effect, the distinction can be summarized as a shift in the rhythm of the wall from karṇa-salilāntara-pratiratha-bhadra-pratiratha-salilāntara-karṇa (KSPBPSK) to karṇa-salilāntara-pratiratha-salilāntara-bhadra-salilāntara-pratiratha-salilāntara-karṇa (KSPSBSPSK).

The overall effect of the insertion of additional recesses in the second group was twofold. On the one hand, it created a clearer hierarchy among āvaraṇa-devatās (surrounding divinities) by creating a clear separation between the most significant deity, situated in a niche on the central bhadra, and the supporting attendant figures on the subsidiary projections. This stood in contrast to the first group (KSPBPSK), where the absence of a salilāntara gave the central bhadra and its flanking pratirathas the appearance of a single clustered unit. On the other hand, the extra salilāntaras offered the possibility for expanding the temple’s sculptural program by increasing the number of spaces for including images. However, in doing so, they simultaneously decreased the width of the surfaces on which individual figures could be carved. To compensate, sculptors did away with framing niches around all but the central bhadra figure. While the inclusion of additional figures no doubt symbolically girded the temple, the increased number of both salilāntaras and divine attendants visually endowed it with a sense of lightness and movement not present along the walls of the structures that followed the first pattern.

Roughly half the temples at Kadwāhā fell into the first stylistic group, and the remainder fell into the second. It might be tempting to see the choice of one type over another as a result of sectarian affiliation, chronological progression, function, or location within the larger village. However, the case is more complicated at Kadwāhā, where both types were employed side by side and often regardless of chronology or cultic affiliation, as can be seen among the temples of the Akhatiavāla, Pachalīvālā, and Nahalvār groups (see, for example, figs. fig. 7, fig. 8). It is possible that the first style (KSPBPSK) was slightly earlier than the second; it is more in keeping with the general style of monuments associable with earlier temples in the region dating to the Gurjara Pratīhāra era. Although additional recesses between the bhadra and pratirathas in central Indian temples appeared increasingly during the ninth century, in the tenth century they became a frequent practice.[45] Accordingly, a number of Kadwāhā’s earlier temples follow the KSPBPSK pattern.[46] However, both styles continued to be employed well into the eleventh century, as can be seen in a comparison of the Mārgatvāla and Toteśvara Mahādeva temples, which follow the first (KSPBPSK) and second (KSPSBSPSK) respectively (figs. 18–19).

Such multiplicities of temple styles and artistic forms are not unknown in medieval India, especially in areas far from the center of a major dynastic state. In such cases, the determining factor may have been the patron. A good case in point is eighth-century Osian, where Michael Meister identified the presence of two patrons on the basis of two distinctive patterns of surface ornamentation. Although Osian’s temples all fell within the same larger category of Maru Style, phase 1, they could be visibly distinguished from one another through the format and framing of sculptural niches on the exterior wall. Meister concluded that while one was the work of the imperial Pratīhāras of Jābālipura (Jalor), the other could be attributed to regional rulers, the Pratīhāras of Māṇḍavyapura (Mandor). At Osian, in particular, he noted that shifts in patronage at a single site attracted new guilds of craftsmen. As a result, not only did architectural knowledge move in from other regions, but the side-by-side exchanges between craftsmen led to dynamic syntheses of regional styles.[47] Such determinations on the basis of patron choice seem particularly likely when other factors—such as sculptural styles, basic iconographies, and local idioms—remain relatively consistent.

It is similarly possible to look at stylistic choices at Kadwāhā as indexes of distinctive patronage. Kadwāhā’s inscriptional record makes it particularly tempting to attribute the first style to the patronage of the Pratīhāras of Buḍhi Chanderī, possibly in collusion with the Mattamayūra sages. As noted above, at least five inscriptions of these local rulers were found at Kadwāhā, most of which are datable between the mid-tenth and twelfth century and all of which were recovered within the vicinity of the monastery and its temple.[48] Perhaps the decision to persist with the older KSPBPSK pattern marked a distinctive endeavor by the local Pratīhāra rulers of Buḍhi Chanderī to establish visual links to a perceived imperial and regional Gurjara Pratīhāra past. By contrast, the insertion of extra recesses, resulting in the KSPSBSPSK pattern, may represent forward-thinking experiments more directly engaged with new transregional movements of architectural ideas. It is likely not coincidental that a number of the temples following the second stylistic pattern also possess forms more commonly seen further west, in the Mahā-Gurjara style associated with Gujarāt and Rājasthān, and that were popular in regional centers associated with larger royal powers, such as the Chandellas and Kacchapaghātas.[49]

At Kadwāhā, such was the case with monuments such as temple 2 of the Pachalīvālā group and the Toteśvara Mahādeva temple in the Morāyat group (fig. 20). In both cases, the introduction of additional recesses was accompanied by a greater complexity of moldings, which include a sculpted diamond band just below the transition from the bhiṭṭa to the pīṭha and a grāsapaṭṭī (gorgon’s-head) band just below the transition from the pīṭha to the vedībandha. In the treatment of the pīṭha, the sequence closely follows that of the Mahā-Gurjara and later the Māru-Gurjara temples, stopping just shy of including the characteristic gajapīṭha (elephant-band) molding commonly seen in western India. In the treatment of the jangha (main wall), however, the Toteśvara Mahādeva comes closest to contemporary developments further west by including stenciled ornamental bands of diamonds, floral motifs, lotuses, and candraśālās along the surfaces of the kumbha moldings.[50] The increasing complexity of the pīṭha and vedībandha moldings seen in these two temples was related, in part, to chronology. In general, earlier temples at Kadwāhā often were built upon a rudimentary jādyakumbha-padma-piṭha, ornamented with lotus petals, underneath a fairly simple vedībandha consisting of khura, kumbha, kalaśa, antarapatra, and kapotāli. Later temples, such as the Toteśvara Mahādeva, exhibit comparatively complex pīṭhas and a greater compression of the vedībandha. However, chronology was not the only factor. Although the Mārgatvāla temple exhibits both a complex sequence of pīṭha moldings and a similar degree of compression in the vedībandha, its base moldings remain comparatively unadorned (fig. 21).

What is particularly striking about these two temples is that neither can be considered a fully developed example of the śekharī mode. Rather, they are what Adam Hardy has designated as examples of “proto-śekharī,” characterized by a “Latina śikhara with small śikhara forms crowning its bhadra and adorning the flanking offsets, but conceived frontally.”[51] In writing about this particular type of proto-śekharī, Hardy noted the curious fact that proto-śekharī are found relatively late in the development of the mode, despite the fact that they appear more rudimentary. Indeed, both the Mārgatvāla and Toteśvara Mahādeva postdate the more famous Lakṣmaṇa and Viśvanatha temples at Khajurāho, which can be seen as fully realized visions of the śekharī mode (fig. 13). Unlike those earlier temples, the śekharī elements at Kadwāhā appear less as an integrated and systematically produced modality than as an applied architectural style. Both the Mārgatvāla and Toteśvara Mahādeva possess central uraḥśr̥ṅgas, but it is only on the Toteśvara Mahādeva that we find the requisite inclusion of kūṭastambhas, albeit only above the pratiratha projection (figs. fig. 18, 22). Nonetheless, these kūṭastambhas lack volume; unlike at Khajurāho, they function as sculptural veneer rather than fully realized and independent architectural elements that would have emerged naturally through a systematic application of the śekharī mode.

It is possible that the appearance of such late proto-śekharī temples at places like Kadwāhā represented a choice on the part of the patron or architect to create a monument that was both like and unlike those built in larger royal centers. Local builders may have sought to emulate and to distinguish their monuments from those affiliated with prominent regional kingdoms, particularly the Chandellas to the west and Kacchapaghātas to the north.[52] However, it is more likely that the architects did not possess the deep and systematic building knowledge required to fully realize the śekharī mode. Thus, when attempting to emulate new forms that were appearing in adjacent regions and subregions, they created a temple that was “śekharī-like,” in effect representing rather than producing a wholly śekharī temple.[53] If this were the case, then the transmission of architectural knowledge should be understood less in terms of region than in terms of urban scale or cultural centrality. While Kadwāhā may have been a big enough place for the idea of śekharī to have circulated, perhaps it was too small and too remote to attract the most prominent architects, who were trained at larger centers.

Tracing Experimentation through Ornamental Forms

While systemic choices, such those as seen through the application of a particular style or mode, indicate the intervention of patrons and architects operating at regional or transregional levels, the ornamental forms that covered the temple’s surface typically fell within the domain of guilds of local artisans. The hand of artisans often is traced through the rubric of idiom, which acts as a counterpoint to style and mode and represents a creative synthesis of and experimentation with outside forms and architectural systems that resulted in the formation of entirely new, locally rooted traditions.[54] One of the most visible examples of a local idiom, born of synthesis and experimentation, is the integration of a particular type of “flaming” niche into several of Kadwāhā’s temples. The niche was composed of two slender kūṭastambhas supporting a highly ornate arch, consisting of a fairly simple illikā-toraṇa, or a gateway (toraṇa) surmounted by little loops resembling the gait of a caterpillar that here take on the form of a flame-like aureole (figs. 23, 24). Very much an exception rather than a rule, these appear on the walls of three of the later temples at Kadwāhā and also occasionally in architectural fragments recovered from the site.[55]

Although new to Kadwāhā, this type of niche gained popularity during the tenth and eleventh centuries across northern and central India.[56] It likely originated in western India, where versions of it can be dated possibly as early as the ninth century in Marudeśa, for example, in the Rāṇcoḍjī temple at Khed, or in the tenth and eleventh centuries at sites such as Osian and Jhālrāpaṭan (fig. 25).[57] By the mid-tenth century, this niche form had spread across the regions north of the Narmada River, where it found particular resonance closer to the major regional centers of Gwalior and Vidiśa, as seen in examples from Buḍhi Chanderī, Cāndpur and Āśapurī (fig. 26) to the south, and Naresar and Sihoniyā to the north (fig. 27).

In most of these cases, this type of flaming niche was used usually on thresholds and in liminal spaces, on doorjambs preceding entry into a garbhagṛha (temple sanctum), on monumental toraṇas (gateways), and also on maṇḍapa pillars.[58] Occasionally, it was applied more prolifically around the temple wall, as at Sihoniyā and Udayapur (see fig. 14). However, at Kadwāhā, artisans introduced a crucial variation that was distinct in terms of placement yet resonant in terms of underlying conceptualization. In the four cases at Kadwāhā where this flaming niche remains intact within a temple program, it appears not on the doorframe but rather on the kapilī, or the segment of the wall that corresponds to the joining of the sanctum with the projecting portico (fig. 28). Despite the shift in its physical placement, the flaming niche seems to have retained its association with a threshold location, one that similarly marked the junction between the entryway and the garbhagṛha.

The type of flaming niche on a kapilī wall seen at Kadwāhā is extremely rare. To date, I have seen only one other example, at the roughly contemporary temple site of Thubon, located approximately twenty miles south of Kadwāhā and likely also situated along the major routes running north and south between the Betwā and Sindhu Rivers (fig. 29). It may represent a local idiom, forged by a guild of artisans working across a tightly knit cluster of sites. At the same time, variations in visual details among the examples, even at Kadwāhā alone, suggests the work of multiple local hands. In the example on the Akhatiavāla temple, the arch is comprised of crisply carved, individual, flaming “leaves” positioned closely together, revealing its likely origin from the compaction of the gavākṣa or caitya arches already present in the udgama (pediment) that had long crowned similar niches (fig. 24).[59] By contrast, in the example on the Pachalīvālā temple, the leaves have become subsumed within a single seamless arch with the individual segments hinted at through the pattern of incised lines (see fig. 23). It may be that this type of variation was less a result of individual artistic practice than of chronology, particularly as later examples, such as those at Thubon, tend to have the same degree of unification and abstraction.

Often the use of an imported ornamental feature in a new manner indicates either a misunderstanding on the part of a local artist or a fundamental shift in meaning. However, in this case, the creative incorporation of newly imported ornamental forms reveals a deep-rooted knowledge of an encoded meaning that was communicated not merely through visual properties but through placement on the temple wall. In utilizing the flaming niche form on the kapilī wall rather than on a doorjamb in the temple’s maṇḍapa, Kadwāhā’s sculptors expressed not only this knowledge but also their willingness to experiment with regionally transmitted forms and to apply them in new, locally specific ways.

This desire to play with both ornamental forms and their meanings is particularly clear in the temple that accompanies the monastery not far from Kadwāhā’s center (fig. 30). Flanking the entrance to the garbhagr̥ha at the level of the doorjambs are a typical grouping of figures, including the river goddesses Gaṅgā (viewer’s left) and Yamunā (viewer’s right), each of which is accompanied by a Śaiva dvārapāla (door guardian) and a female attendant. At first glance, the jambs appear to follow a typical pattern continuing from the late Pratīhāra era: Gaṅgā and Yamunā stand closest to the sanctum’s entrance, and the male dvārapālas, one fierce (left) and one pacific (right), are positioned prominently just below the central śākhā (sculptural band). On closer examination, however, it becomes apparent that the two dvārapāla figures are carefully differentiated. Following the Pratīhāra-era tradition, the figure on the right stands on a simple base. In contrast, the fierce dvārapāla on the left is embellished by flame-like halo that extends above him from shoulder to shoulder (fig. 31). In form, this flame-like halo is excerpted from the flaming niche, which, at other contemporary sites, often was used to frame the dvārapāla situated at the entryway to the garbagr̥ha (see figs. fig. 25, fig. 26). In this case, the independent architectural motif has been transformed into a powerful force emerging from the fierce dvārapāla’s body.

In this particular instance, the transformation of a flaming niche into a flaming halo makes sound iconographic sense as it visually draws attention to Śiva’s capacity for destruction embodied through his fierce incarnations. However, in this case, the choice may have carried site-specific associations connected to the nearby Śaiva monastery. According to a tenth-century fragmentary inscription found on-site, the monastery was home to a group of prominent ascetics, who were known to have engaged regularly in the practice of yoga and tapas (austerities) associated with the generation of tejas (flaming light or energy).[60] In addition to these ongoing practices, the inscription details a story that particularly resonates with the idea of an internally generated flame. At one point in the monastery’s history, a resident sage named Dhārmaśiva was approached by a loyal local chief seeking redress for an injustice perpetrated by a rival that resulted in some deaths. Upon hearing his story, Dharmaśiva became extremely angry and “shed tears released out of compassion, just for a moment, after which his [eyes] became very red with anger ... like a flash of lightning.”[61] He then began “blazing” like “another Śiva on earth,” and, after conjuring weapons through the power of his flaming energy, he set off to follow in the footsteps of Śiva as “destroyer of the three cities” to conquer “the entire collection of enemies.”[62] It is just possible that the transformation of the flaming niche into a flaming halo may have resonated with the potential of resident Śaiva practitioners to become divine guardians, who embodied both the destructive and pacific qualities of Śiva.

In such a case, ornament was not merely as an extraneous decorative art but a deeply coded language that carried multiple associations and functioned as a medium through which knowledge was transmitted across wide geographic regions. The transformation of flaming niche into flaming halo at Kadwāhā was both new and locally specific. And yet, even still, it preserved the broader transregional association of the ornamental form with architectural thresholds through its application specifically on the sanctum door. In a sense, this example from Kadwāhā serves as a case through which decorative forms carried deeper meanings and ornament operated as iconography, laden with symbolic meaning.

Religious Iconographies and the Movement of Sages

The transformation of ornament into iconography in the temple accompanying the monastery suggests that certain types of formal changes were driven not merely by aesthetic but also by religious concerns. It may be that the monastery’s resident sages played a defining role in the development and transmission of key sculptural and architectural ideas. The monastery also reminds us that, although the identity of temple patrons and artisans at Kadwāhā remains to large extent conjectural, we are in the unusual position of knowing the religious affiliation of some temples, which no doubt were associated with the Mattamayūra sect.[63] This is particularly the case for the temple accompanying the monastery, likely was built under the direct supervision of the presiding Śaiva ācāryas. Iconographic decisions probably were made not only because of the preferences of royal patrons but because of ritual requirements associated with an authoritative religious sect. Because the Mattamayūras have left a substantial epigraphic record in many places across central India, it is possible to map the movement of sages from site to site and across wide areas by following the genealogies that their inscriptions provide. The iconographic interventions at these sites suggests that the transmission of religious knowledge across larger regional and transregional areas was connected to the movement of lineages of sages.

Like most of Kadwāhā’s temples, the one standing next to the monastery is pañca-ratha in plan, and like many central Indian temples built to house a Śiva liṅga, it faces west (figs. fig. 2, fig. 16). In style, it follows the pattern associated with earlier temples of the Gurjara Pratīhāra era, as noted above. It stands on a low jādyakumbha-padma-piṭha, above which rise the expected base moldings, including the khura, kumbha, and kalaśa moldings of the vedībandha. The jangha is divided into two horizontal levels. On the karṇa, kapilī, bhadra projections, the lower level is reserved for a main image framed by a niche, while the upper provides the space for the crowning udgama. By contrast, both rows are filled with images on the pratirathas and salilāntaras. The choice of framing is rooted in a iconological logic that reveals a distinct hierarchy among images. Whereas the karṇas, bhadras, and kapilīs generally contain clearly identifiable iconographic sets, the images on the pratirathas and salilāntaras invariably represent minor divinities and attendants. Thus, the smaller niched figures on the karṇas contain the dikpālas (guardians of the directions), the ones on the kapilī contain protective goddesses, and the largest niches, situated at the center of the wall, are reserved for the āvaraṇa-devatās, or deities directly related to the enshrined god. By contrast, the images on the pratirathas and salilāntaras include surasundaris (beautiful women), vyālas (mythical beasts), and mātr̥kās (mother goddesses). The jaṅghā is capped by a grāsapaṭṭī, above which rise a typical set of varaṇḍikā moldings. The tall śikhara (tower) that once rose above the building has long been lost.

While in its primary features, the temple standing next to the monastery is fairly typical, a few things distinguish it from the others at Kadwāhā. The first is the ornamentation of the vedībandha, particularly the use of niche figures in the kumbha and kalaśa moldings (fig. 16). Although it is not uncommon to find small figures in niches on the kumbha and kalaśa moldings, they more often were confined only to the position of the central bhadra (figs. fig. 6, fig. 8, 17–18, fig. 29). In the temple accompanying the monastery at Kadwāhā, niche figures appear not only on the bhadra but on every projection of the temple wall. While this particular choice is unique at Kadwāhā, it is present elsewhere in central India, most notably in temples at other Mattamayūra sites. A good case in point can be seen further north at the Mattamayūra monastic site of Surwāyā, which stood approximately fifty kilometers north of the junction between the Ahīrāvati and Sindhu Rivers, likely on the route leading to Narwar and Pawāyā (figs. fig. 10, 32).

Three other iconographic details connect the monastic sites at Kadwāhā and Surwāyā. The first two require close attention to the treatment of the sculptural program on liminal and interstitial segments of the temple wall. The first can be identified through the application of a carved lotus extended along the outer edges of the karṇas and straddling the point of transition from one cardinal plane to another (figs. 33, 34). Although this way of treating the corners is not found elsewhere at Kadwāhā, it can be seen in at least two of Surwāyā’s surviving temples and traced to points further west in Uparamāla.[64] As in the case of the flaming niche discussed above, positioning lotuses across the juncture of two cardinal walls is not merely ornamental but of iconological significance. Corners were potentially vulnerable points of a temple plan, and it was important to gird them symbolically through the installation of potent protector deities, such as the dikpālas and other auspicious imagery.[65] The lotus may have been selected because of its flower’s auspiciousness in Indic religious traditions. But it is also possible that it carried greater meaning in the context of a Śaiva and, even more specifically, a Śaiva Siddhānta monastic complex, where a maṇḍala in the form of an eight-petaled lotus was drawn or visualized regularly as part of the ritual daily regimen and where Śiva’s seat of worship was understood as a fully blooming lotus (padmāsana).[66]

The second can be located in the insertion of a full set of sapta-mātr̥kās (seven mother goddesses), framed by Śiva and Gaṇeśa, in the recesses between the pratiratha and karṇa niches, seen most clearly in the upper salilāntara of the temple at Kadwāhā (figs. fig. 16, 35). It is not surprising to find sapta-mātr̥kā sets on the temples at Kadwāhā and Surwāyā, as they had become a standard part of the iconography of Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava, and Śakta temples by the middle of the tenth century. However, in most cases in central India, the set usually was encountered on the lintel of the doorframe leading to the garbagr̥ha or, less frequently, in niches woven around the lower exterior moldings of the temple’s vedībandha, as they are in Khajurāho (see fig. 13).[67] Only one other temple at Kadwāhā, the early eleventh-century Mārgatvāla, makes a similar iconographic intervention; however, in that case, the mātr̥kā set is on the upper portion of the pratiratha projections rather than in the recesses (fig. 18). A closer comparison can be found at Surwāyā, where a mātr̥kā set was similarly positioned in the recesses between the pratirathas and karṇas, although in the lower rather than the upper level of the jangha.[68] The appearance of the mātr̥kās in the salilāntaras, although uncommon, is not unknown and can be found also in the Nīlakaṇṭheśvara temple at Kekind in Rajasthan.[69]

The third iconographic link between the two sites is not only more immediately obvious but also more important, as it pertains to the iconography of doorframe leading into the temple’s sanctum. More specifically, at both sites, we find an image of Śiva as the dancing god Naṭeśa in a highly prominent location, at the center of the door lintel (figs. fig. 30, 36). At Kadwāhā, Naṭeśa appears in the lalatabimba (central position on a door lintel), a spot most often reserved for an incarnation of the main deity. Although his lower legs and a number of his arms have broken off, his primary iconography remains clear. He wears his hair high in a mass of matted locks (jaṭāmukuṭa), and he is depicted with his knees bent in a dancing posture. His lower left arm is flung diagonally downward with his hand pointing toward what would have been his foot. In his upper right and left hands respectively are a trident and a khaṭvāṅga (skull-topped staff). Accompanying him in niches on the corners of the lintel are the gods Brahma and Viṣṇu, accompanied by their consorts, and the space between is filled with the navagrahas (nine planets).[70]

At Surwāyā, Naṭeśa dances in the center not of the lintel proper, but of the architrave above (fig. 37). He is flanked by Gaṇeśa and, on his right, his consort, Vighneśvarī, and Viṣṇu with, on his left, his wife, Lakṣmī, each of whom is surrounded by musician figures. Within the niches at either corner are two other active forms of Śiva: to the god’s left is Śiva-Vīṇādhara, or Śiva holding a stringed instrument (vīṇā), and to his right is the ferocious Bhairava, often associated with Śiva’s pure destructive power. The lintel proper displays Viṣṇu on Garuḍa in the center of the lintel, Brahma and Viṣṇu at the corners, and the navagrahas in-between. While this may seem to belie the notion that this temple was originally dedicated the Śiva, it actually follows an older tradition seen in many earlier Pratīhāra-era temples, including the Śiva temple accompanying the Mattamayūra site at Terahi.[71] In this earlier tradition, Michael Meister has suggested, Viṣṇu represented Lokeśvara, or the world protector, and acted as a charm rather than as a marker of cultic affiliation.[72]

Although it became more common to display Śiva as cultic marker in the lalāṭabiṁba of the door lintel by the tenth and eleventh centuries, images of Śiva as Naṭeśa are comparatively rare. Yet at Mattamayūra monastic sites, Naṭeśa appears frequently in central positions on the doorframe. Within Kadwāhā alone, two other doorframes prominently feature Naṭeśa at the center of the door lintel. The first is at the late ninth-century Caṇḍāla Maṭh, the earliest temple in Kadwāhā proper, and the second is on a sculptural fragment that once belonged to a lost temple in the vicinity of the monastery (fig. 38). Additional examples can be found at other Śaiva monastic sites, including Terahi and Buḍhi Chanderī in Gopakṣetra and Koḍal, and Chandrehe further to the east in the Kalachuri kingdom in Ḍāhaladeśa (fig. 39).[73] With the exception of the figure at Surwāyā, these all are depicted as multiple-armed deities carrying a trident and a khaṭvāṅga.

The geographic span of these sites is quite broad, extending across 220 miles from Kadwāhā and its associated cluster of sites. The journey itself may have crossed two regional kingdoms and have been closer to four hundred miles following typical routes. Nonetheless, inscriptional evidence makes clear that this was a journey traveled by Mattamayūra sages. For example, inscriptions from sites in eastern Madhya Pradesh describe the movements of a guru named Prabhāvaśiva from the vicinity of Kadwāhā. Initiated and trained by a guru named Śikhāśiva, Prabhāvaśiva was recruited by the Kalachuri king Yuvarajadeva (reigned 915–45) to head a monastery that he had built at Gurgī.[74] Prabhāvaśiva’s successor at Gurgī, Praśantaśiva, then established a peaceful aśrama (hermitage) near the Son River at Chandrehe. To get from Kadwāhā to Chandrehe, Prabhāvaśiva may have followed southern routes along the Betwā River and then headed east in the land above the Narmada toward the Kalachuri royal capital of Tripurī. From there, he may have traveled north along the Son River to get to Gurgī and then Chandrehe, possibly stopping along the way at Bilhari, Nohta, and other important tenth-century temples and monasteries (fig. 40).

The significant links between sect and site established through iconography were reinforced by Mattamayūra inscriptions, which emphasized the power of Śiva’s frenetic yet blissful dance. Although the fragmentary inscription found in the maṭha at Kadwāhā no longer retains its invocatory verses, Mattamayūra inscriptions from other sites almost invariably open with praises of Śiva’s dance, employing language that indicates both reverence and fearful fascination with the power of the god’s movements.[75] For the Mattamayūras, these movements may have taken on meaning as actions that could bring about liberation and destruction on a cosmic scale. For example, an inscription affixed to a monastery at Ranod describes Śiva’s dance as follows:

May the fully formed posture of dancing Śiva, remover of all sin, grant to you the things that are best (liberation). Although [his dance] is joyful and performed with care, it causes anxiety to both the gods and demons through its vehemence, as [it] destroys [even] the stability of [the sacred] Mount Kailasa, which bends at the pounding of [Śiva’s] foot.[76]

At Chandrehe, the dance is similarly evoked as frantic and wild and also as carrying the potential for bliss and liberation:

The great snake’s hood bows down as the bowl of the Earth spins, turned by nimble feet dancing a quick step. The elephants of the quarters flee. The Cosmic Eggshell whirls without end, twirled by his long arms to the dense beat of the damaru drum. May Śiva’s wild dance bring you delight (liberation)![77]

In addition to connecting widely disparate Mattamayūra sites across several hundred miles, the visual emphasis on Naṭeśa puts Kadwāhā into dialogue with an even vaster transregional geographic arena. Although the Mattamayūras are understood as a central Indian lineage, they belonged to the larger religious tradition of Śaiva Siddhānta, which gained prominence during the tenth and eleventh centuries through the patronage of many major regional and imperial rulers. Most significant, Śaiva Siddhānta became the state religion under the Cholas in Tamil Nadu in the far South, under whom the famed Śiva Naṭarāja (Lord of the Dance) icon was formed and widely circulated, both in the form of bronze sculptures and within the sculptural imagery of the South Indian temple wall. In the past, the Naṭarāja was tied to South Indian regional concerns and particularly to the sacred temple at Chidambaram.[78] However, the growing importance of Naṭeśa at Mattamayūra sites, and elsewhere in temple programs across northern and central India, suggests that Śiva’s dance was an important emblem, possibly connected with Śaiva Siddhānta at a transregional level.[79] In the case of the Mattamayūras, the links across regions can be traced concretely through inscriptional evidence, which confirms that the lineage had close ties to regions much further south, with branches in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu.

Conclusions: Artistic Eclecticism and the Transmission of Architectural Knowledge

The interconnection of networks, reinforced through iconographical and inscriptional links between sites, may help us formulate new understandings of the many variables underlying the creation of temples at places such as Kadwāhā. Through variation, we can see how multiple patrons operated simultaneously, and diverse individuals were involved in the determination of temple style, format, and sculptural program. When artistic styles or idioms proliferate or repeat themselves, we can deduce the movement of artist communities or the intervention of specific patron. The extension of key iconographies across regions may illustrate the transmission of religious knowledge through monastic networks. In the case of the Mattamayūras, this transmission can be mapped spatially by following the movement of individual teachers recorded in inscriptions. Locating the source of a form’s reproduction—through patrons, artisans, and religious teachers—represents a key first step in the process of tracing the movement of architectural knowledge and the mechanics of its transmission. The second step is to identify the ways in which that knowledge was modified and adapted to new local circumstances, potentially formulating what George Kubler referred to as new “prime objects.”[80]

Unfortunately the fragmentary inscriptional record provides only limited information about the identities of individuals involved even in the foundation of Kadwāhā’s monuments, let alone the structure of artisan guilds or architectural education in medieval central India. A wide array of textual materials gives some sense of ancient and medieval architectural practices for a range of social categories and classes of artisans. In ancient India, as R. N. Misra has shown, distinctions were made between brickmasons (iṭṭhakāvaḍḍhakī), stonemasons (sela-vaḍhakī), and stone polishers (miṭhika) as well as menial laborers or workmen (karmika, navakarmika).[81] The evidence suggests the participation of both resident and itinerant guilds of artisans during the Gupta period.[82] By the sixth and seventh centuries, the post-Gupta period, the sūtradhāra (architect) was more prominent as a class of artisan involved in building activities. In addition to the sūtradhāra was the sthapati, who may have functioned as the director or consulting architect, and the sūtragrāhin, who was required to be proficient in draftsmanship and may have supervised the vardhakī (carpenter) and takṣaka (cutter or carver).[83]

Because occupational divisions often are described in texts as divine emanations, the extent to which they reflect a real rather than ideal division of labor in places like Kadwāhā unfortunately remains unknown. However, it is likely that sthapatis played a crucial role in the design of buildings around the turn of the millennium, as indicated by the careful attention given to their qualifications by the Paramāra king Bhoja (reigned 1010–55) in the Samarāngaṇasūtradhāra. According to that text, sthapatis had to be well trained in both theory and practice and architecture and sculpture. It is likely that, because of their special training, highly trained sthapatis were in great demand. They may have traveled widely to fulfill new commissions. It is possible, therefore, that the overall plan of Kadwāhā’s temples may have been designed by a range of sthapatis trained in larger centers to the north and south, such as Gwalior and Vidiśa, who went to Kadwāhā principally when commissioned to design a new building. In contrast, the actual laborers were far more likely to be local.

Although the actual mechanics of transmission are often extremely difficult to trace in places such as early medieval southern Gopakṣetra, one can begin to imagine the ways in which architectural ideas traveled across regions. While the systemic variations in temple plans and elevation likely fell within the domain of architects and patrons, the application of distinct ornamental features probably was tied to other factors, including the movement of artisans and the practices of local sculptors. Modes operated on the deepest level, like a mathematical formula or vector diagram, informing the entire process of erecting a building. To employ a new mode thus required an architect well schooled in the principles of its design, possibly a sthapati who had a transregional repertoire of forms and designs. Stylistic distinctions, such as those seen at Kadwāhā, operated on the levels of both wall and plan, but in ways that remained fundamentally articulated through the framework of the temple’s surface. Similar styles could be applied easily to temples executed in different modes, as seen in the case of the Mārgatvāla and Toteśvara Mahādeva temples.

Ornament, by contrast, often is relegated to a secondary position, one primarily confined to a building’s surface. However, it can carry quite broad implications. Often associated with local artisans, ornament was not only a temple’s most variable feature, it was the one that traveled most readily through a range of media and movable objects. Located along larger routes, Kadwāhā’s temples likely encountered a variety of luxury goods, which may have included textiles, small sculptures in ivory or ceramic, metal objects, and jewelry.[84] At Kadwāhā, the transmission of ornamental forms occurred in a manner that was imbricated with a deep awareness of their meanings, as seen in the experimentation with the flaming niche form. At the same time, certain elements of the temple’s sculptural imagery seem to have been determined not by local artisans, but by transregionally mobile religious practitioners, as was the case with the appearance of the khaṭvāṅga-bearing Naṭeśa on door lintels at multiple Mattamayūra sites. To reproduce Naṭeśa in this way required the knowledge of ritual practitioners. The hand of the artisan, however, remained visible in the local idiom, or the style of the actual carving.

Ultimately places like Kadwāhā are hard to study; the paucity of confirming data provided by textual sources leaves much more to the realm of conjecture than to the realm of hard fact. Nonetheless, the visual complexity at the levels of monument and site serves an indexical function, providing traces of human interaction and the dynamism of artistic practice. At Kadwāhā, the monuments themselves serve as a testament to the movement of people and ideas. Through their forms, they gesture toward the movement of art and architectural ideas as they followed architects and artisans, royal patrons and resident communities, and monastic institutions. That the paths they point toward map onto later routes and narratives of travel, such as those followed by Ibn Baṭṭūṭa in the fourteenth century, make it all the more possible to reimagine them in earlier periods. At Kadwāhā during the tenth and eleventh centuries, the transmission of architectural knowledge occurred at a level that can be deduced only by recognizing sculptural and structural details not merely as passive continuities or examples of broader and easily fixable traditions, but as indexes of architectural practices and artisans who were fully able and eager to creatively engage with old and new visual forms.

Notes

This account is glossed from translations of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s Riḥla by Samuel Lee, trans., The Travels of Ibn Batūta (London: Oriental Translation Committee, 1829), chap. 16–17; and by H. A. R. Gibb and Charles Beckingham, trans., The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (A.D. 1325–1354), vols. 3–4 (Cambridge: London: The Hakluyt Society, 1971/1994); and H. A. R. Gibb, trans., Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1929; reprint, 1957).

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa notes that “the lieutenancy of Dawlatābād extends through a distance of three months.” See Lee, The Travels of Ibn Batūta, 162.

For a brief sampling, see Richard M Eaton, A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761: Eight Indian Lives (Cambridge University Press, 2005); Irfan Habib, Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500 (New Delhi: Pearson Education India, 2011); Mehrdad Shokoohy, Muslim Architecture of South India: The Sultanate of Ma’bar and the Traditions of the Maritime Settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa) (London: Routledge, 2003); Andre Wink, Al Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 2, The Slave Kings and Islamic Conquest in the 11th–13th Centuries (Leiden: Brill, 1997); Peter Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Catherine B. Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India Before Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

For studies on Gwalior and Chanderī, see Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty, Gwalior Fort: Art, Culture, and History (New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann, 1984); Gérard Fussman et al., Naissance et déclin d’une qasba: Chanderī du Xe au XVIIIe siècle, vol. 2 (Paris: Boccard, 2003).

The term is transliterated as Kajarrā in Gibb and Beckingham, The Travels, 790, and as Kajwarā by Lee in The Travels, 162.

Although we do not have textual accounts confirming Kadwāhā’s official status as a ribāṭ, the archaeological context seems to fit such an assignation. I have treated this issue more extensively in a previous publication. See Tamara I. Sears, “Fortified Maṭhas and Fortress Mosques: The Transformation and Reuse of Hindu Monastic Sites in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries,” Archives of Asian Art 59 (2009), 25–26.

See Annette S. Bevridge, trans., The Babur-Nama in English (London: 1922), 590–91; W. M. Thackston, trans., The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1996). While Beveridge reads “Kachwa,” Thackston reads “Kachwaha.” Beveridge also noted the possible correspondence between Kachwa and Kadwāhā (p. 591).

Although not explicitly recorded in the extant corpus of earlier travelers’ reports, this particular central Indian route continued to be used during the Mughal era, as attested to by the writings of other foreign travelers, including Father Antonio Monserrate (1579–82), Niccolao Manucci (1655–56), and Peter Mundy (1632–33). See, for example, Michael Fisher, Visions of Mughal India: An Anthology of European Travel Writing (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007), 42–46, 121–24; R. C. Temple, ed., The Travels of Peter Mundy, in Europe and Asia, 1608–1667, vol. 2, Travels in Asia, 1628–1634 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1914). See also Dilip Chakrabarti, The Archaeology of the Deccan Routes: The Ancient Routes from the Ganga Plain to the Deccan (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2005), 123–43.

While a full analysis has yet to be published, my preliminary field surveys have revealed many additional moments of building, extending from the fifteenth century through the colonial era and into the present day.

According to the 2011 Census of India, the population included 819 households with a total of 4,572 people. It is useful to note that the population has increased significantly over the past century. The population was recorded as 826 (433 males and 393 females) in 1901, in Charles Eckford Luard’s Central India state gazetteer series, vol. 1 (Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, 1908), 247.

Although not widely known among scholars, Bījāsan Devī occupies a position of regional prominence in central India and particularly in areas north of the Narmadā river. One of the more famous temples associated with this goddess is on a hilltop in Salkanpur, which is approximately 58 miles south of Bhopal. The temple at Kadwāhā appears, on the basis of style, to date to the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

I mapped a number of fragments while conducting fieldwork in the fall of 2012.

Madhusudan Dhaky and Michael W. Meister, eds., Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture (EITA) (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1998), vol. 2, pt. 3, 21–27.

The temple itself was likely buried at one point under a platform that once supported a small mosque built in the early fourteenth century, when the gaḍhī surrounding a Śaiva core was transformed into an Islamic ribāṭ. On the chronology of the fortress and ribāṭ, see Sears, “Fortified Maṭhas.” On the dating of the monastery, see Tamara I. Sears, Worldly Gurus and Spiritual Kings: Architecture and Asceticism in Medieval India (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), chap. 3.

R. N. Misra, “Religion in a Disorganized Milieu,” in Organizational and Institutional Aspects of Indian Religious Movements, ed. Joseph O’Connell (New Delhi and Shimla: Manohar and the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1999). Misra’s arguments are rooted in several decades of fieldwork, during which he noticed the high number of abandoned villages in the archaeological record and other evidence suggesting the relative itinerancy of the region’s population in antiquity (p. 72, n. 11). For an extended discussion of the relationship between jānapadas and the relationship between inhabited and wilderness spaces during this particular period in northern and central India, see Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya, “Historiography, History and Religious Centers: Early Medieval North India, circa AD 700–1200,” in Gods, Guardians, and Lovers: Temple Sculptures from North India, A.D. 700–1200, ed. Vishakha Desai and Darielle Mason (New York and Seattle: Asia Society Galleries in association with University of Washington Press, 1993), 36–46.

For more on geography, see Michael Willis, “An Introduction to the Historical Geography of Gopakṣetra, Daśārṇa, and Jejākadeśa,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 51, no. 2 (January 1, 1988), 271–78; Michael Willis, Temples of Gopakṣetra (London: The British Museum, 1997), 16–18; and Pranab Kumar Bhattacharyya, Historical Geography of Madhya Pradesh from Early Records (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1977).

At their point of junction with the larger Yamunā in the north, the two rivers remain separated by more than 100 kilometers, and their paths take them on a winding parallel journey that is separated most of the way by distances of anywhere between 50 and 150 kilometers.

The route along the Sindhu and its tributaries appear to have served as a major throughway centuries later for Ibn Baṭṭūṭa in his passage from Gwalior to Narwar and then onward to Chanderī, which is located directly along the Betwā River, just 25–30 kilometers southeast of Kadwāhā. While the route along the Betwā has been noted in the past, most recently by Dilip Chakrabarti, scholars seem to have missed the importance of the Sindhu, Mahuār, and Ahīrāvati for understanding routes of travel and the connection between places, in part because sites such as Kadwāhā remain largely understudied. Although Chakrabarti notes the routes along the Betwā and Chambal Rivers, he omits the Sindhu and its tributaries from his discussion of ways to and from Pawāyā. See Dilip Chakrabarti, The Archaeology of the Deccan Routes: The Ancient Routes from the Ganga Plain to the Deccan (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2005), 94–101, esp. 104–5.

For more on Padmāvatī and the nāgas, see H. V. Trivedi, Catalogue of the Coins of the Nāga Kings of Padmāvatī (Gwalior: Dept. of Archaeology & Museums, Govt. of Madhya Pradesh, 1957); Gwalior Museum, Madhya Pradesh (India), and Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Terracottas of Pawaya: Central Archaeological Museum, Gujari Mahal, Gwalior. ([Bhopal]: Commissioner, Archaeology & Museums, Madhya Pradesh, 1990).

S. Sankaranarayanan and G. Bhattacharya, “Mahuā Inscription of Vatsaraja” Epigraphia Indica 37 (1967), 53–55.The inscription is affixed to the maṇḍapa (portico of Śiva temple 1, otherwise known as the Dhūrjaṭi Śiva temple, at Māhua, which is located approximately ten kilometers northeast of Kadwāhā. This Vatsarāja should not be confused with the later Vatsarāja (circa 777–808) of the Gurjara Pratīhāras.

This aspect of the inscription has led some scholars to conclude that Mahuā, at the very least, was “no provincial backwater” but rather fell solidly “on the main line of communication between Kānyakubja and Vidiśa” (Willis, Temples, 17).

V. V. Mirashi was the first to note that the Madhumatī River is mentioned in Bhavabhūti’s Mālatīmādhava; see his essay, “The Śaiva Ācāryas of the Mattamayūra Clan,” Indian Historical Quarterly 26 (1950), 6, n. 10. On Bhavabhūti’s place of origin, see V. V. Mirashi, Bhavabhutī (1974, rpt. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1996), 32–44.

In that play, Saudāminī travels to Padmāvatī from the sacred center of Śrisailam in modern-day Andhra Pradesh; in the process, she describes the flowing waters at the confluence of the Madhumatī and Sindhu Rivers. The description occurs at the opening of act 9. See Bhavabhūti, Bhavabhūti’s Mālatīmādhava, with the Commentary of Jagaddhara, ed. and trans. M. R. Kale (Bombay: Oriental Publishing, 1908), 79–80.

Michael Willis, Inscriptions of Gopakṣetra: Materials for the History of Central India (London: British Museum, 1996), 2.

R. N. Misra, “Śaiva Siddhānta,” in Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India, ed. J. S. Grewal (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006), 54, 64, n. 77. For further connections to Gwalior, see Willis, Inscriptions, 2, n. 7, 109, and Arvind K. Singh, “Lintel Inscriptions from Gwalior,” Journal of History and Social Sciences 4, no 1 (July–December 2012).

F. Kielhorn, “Two Inscriptions from Terahi, [Vikrama-] Samvat 960,” Indian Antiquary 17 (1888), 201–2.

An edition of the inscription and a description of its contents can be found in F. Kielhorn, “Siyadoni Stone Inscription,” Epigraphia Indica 1 (1889), 162–79.

The term mahārājādhirāja is used in verse 22 of the Siyaḍoṇī inscription, and the term nr̥pacakravarttī is found in the fragmentary inscription from Kadwāhā. For more on imperial titles, see B. N. Puri, History of Indian Administration, vol. 2, Medieval Period (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1975), pp. 2–4; D. C. Sircar Indian Epigraphy (Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, 1965), 330–51.

V. V. Mirashi and A. M. Shastri, “A Fragmentary Stone Inscription from Kadwaha,” Epigraphia Indica 37 (1968), 117–24.