- Volume 44 | Permalink

Following in the footsteps of archaeology, library and museum informatics and the digital humanities, art history recently has been engaging more deeply with the digital turn in humanities scholarship. Students and scholars of the arts and visual cultures of the Islamic world may find it worthwhile to study this development and consider what their involvement will be.

In many ways, digital art history is already here. Museums make their collections available online; scholarly articles and books are accessed through online databases; and photography today is primarily digital. But explorers of digital art history are interested in leveraging the diverse powers of computers and software to forge new insights in the field and new modes of communication. They are equally interested in exploring how the practice of art history, and the humanities in general, can transform the digital world in which we all live, instead of the other way around.

UCLA’s Beyond the Digitized Slide Library

In 2014, the Getty Foundation sponsored three summer institutes, one of which was held at the University of California, Los Angeles. Called Beyond the Digitized Slide Library, it was conceived and taught by UCLA professors Miriam Posner, Johanna Drucker, Todd Presner, and Steven Nelson and guest instructors Murtha Baca, Zoe Borovsky, Christian Huemer, Lisa Snyder, and Yoh Kawano. The instructors offered valuable insights and they have gathered many helpful resources and sample projects, which are available on the institute’s website.

Drucker clarified that digital art history can be seen as an extension of eighteenth-century encyclopedic and quantitative turns in Euro-American knowledge production. It can refer to any art historical project that can be made computationally tractable. Systematically collecting, organizing, structuring, and ensuring consistency in research information —that is, data modeling, creation, and cleaning— all in ways that can be imported by appropriate software is key and the most time intensive. The good news is this requires minimal technical expertise and computational tools, but it does require the adoption of a particular mindset. Anyone who can assemble his or her research information into a spreadsheet is well positioned to practice digital art history.

Posner explained that digital scholarly projects, whether simple or complex, can be broken down into the sources to be used, how they should be processed, and how they will be presented. As Drucker put it, projects typically involve three phases: digitization, data creation, and augmentation of the data created.

Both she and Baca stressed the importance of collaboratively determined standards and consistencies in naming, categorization, and metadata creation across the humanities and art history. For example, the Getty has been developing the Cultural Objects Name Authority to establish consistency. Without standards and adherence to them, digital scholarly projects cannot not be integrated with one another, that is, be interoperable, which is necessary to realize one of the great promises of the digital humanities—large-scale research inquiry. Once again, it is not essential to have technological proficiency, but one must have a deep commitment to consistency and collaborative scholarly practice, in which data sets are openly shared.

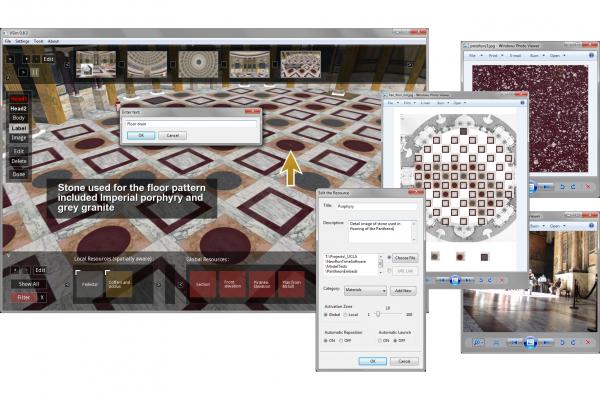

Presner spoke about the concept of “thick mapping,” exemplified by the Hypercities project he helped lead. He stressed the importance of separating one’s data and data models from the digital platforms and presentation tools used. As digital technologies become obsolete and new ones emerge, one’s research data and data models can then be carried forward. He and Snyder cautioned that custom software tool development is extremely time and resource intensive. Snyder demonstrated her impressive 3D pedagogical tool VSim, a prototype that can be downloaded, and also made the compelling case that 3D modeling itself is a form of scholarly inquiry.

Kawano and Borovsky showed the power of freely available interactive visualization software, such as Google Fusion Tables, Palladio, and Gephi. Research information assembled in spreadsheets combined with a basic knowledge of these tools can lead to impressive results surprisingly fast. However, Drucker cautioned that seductive data visualizations often conceal as much as they reveal and require scrutiny.

Finally, all of the scholars stressed the importance of being transparent and critically reflective about the rhetorical dimensions of categories used in data models, the vocabularies instituted, and the modes of presentation chosen, particularly visualizations. Just as historians have practiced source criticism, scholars should practice a rigorous criticism of digital modes of constructing and presenting knowledge.

Possible Paths

For Islamic art history and related fields to participate in digital art history, here are some thoughts on what needs to occur. Following the examples of countries in East Asia, North America, and Europe, a consortium of states from the Islamic world should provide significant financial and technological support to systematically and comprehensively digitize collections, sites, manuscripts, and texts pertinent to Islamic world studies and its subset, Islamic art history. The British Library Qatar Foundation Partnership is a promising start in this direction. These states should commit to universal, shared scholarly values and principles. By digitization, I also mean data cleaning; transcription; OCR work in scripts from the Islamic world, such as Arabic calligraphy; and information repositories and systems. These activities cannot be the sole responsibility of Euro-American nations or individual scholars.

An international alliance of librarians, museum cataloguers, and research scholars from around the world, especially the Islamic world, could focus on establishing metadata standards, controlled vocabularies and crosswalk tables, and other kinds of standards for the field and engage with broader initiatives like those of the Getty Research Institute and organizations like the College Art Association.

In terms of pedagogy, undergraduate and graduate students require training in digital modes of scholarship, which could potentially improve their employment prospects in the marketplace and the academy.

Finally, the Islamic art history scholarly community should embrace the emerging ways of recognizing and peer-reviewing digital art historical scholarly projects, whether they be metadata creation, database development, 3D-model development, network analyses, or whatever other forms emerge.

Digital art history offers considerable promise for enriching the field of art history, and Islamic art history can only benefit from engaging with the digital turn in humanities scholarship.

Ars Orientalis Volume 44

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0044.012

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.