- Volume 44 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.5mb

Abstract

Grave goods of the Koryŏ Kingdom first came to public attention after they were found by accident in the late nineteenth century. During the colonial period (1910–45), Japanese archaeologists surveyed Koryŏ royal tombs, but they took no interest in other types of graves from this period. Since the 1980s, hundreds of pit graves have been unearthed in the southern part of the peninsula, often as a result of construction work, enabling a broader understanding of Koryŏ burial practices. Most pit graves contain no objects, but some have yielded celadon ceramics and unglazed stonewares as well as different kinds of metalwares, usually bronze spoons, hairpins, and occasionally mirrors. In some instances, iron scissors have also been found. This article presents an analysis of typical grave goods found in royal tomb chambers and pit graves, and discusses their locations within the graves and their significance as burial objects.

Tombs dating to the Koryŏ Kingdom (918–1392 CE) first came to public and scholarly attention in the late nineteenth century thanks to accidental discoveries. Collectors and curators were especially interested in the ceramic wares, mostly celadons, that were unearthed. This interest lead to systematic searches for tombs and their grave goods, which included various kinds of metal objects, beads, and coffin ornaments in addition to ceramics. Nowadays, celadon ceramic wares tend to be displayed in a manner that emphasizes and enhances their aesthetic appeal and visual characteristics, and rarely alludes to their use as burial goods. This was not always so. Between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, it was common knowledge that celadons were removed from tombs, and until the 1960s they often were referred to as “tomb goods” or “mortuary wares.”[1] However, from the 1970s onward such terminology disappeared from scholarly writings, and they are no longer labeled primarily as burial objects.[2] This paper aims to reposition celadon wares and other Koryŏ artifacts within their original context of use as grave goods through a discussion of typical burial artifacts, their locations within the graves, and their significance as tomb objects.

Interest in the arts of Koryŏ developed during the early Chosŏn Kingdom (1392–1910) out of scholarly engagement with the historicity of the period. In the late sixteenth century, scholars began to visit Sungyang sŏwŏn 崧陽書院, a Neo-Confucian academy that was established in the Koryŏ capital of Kaesŏng in commemoration of the Neo-Confucian scholar Chŏng Mong-ju 鄭夢周 (1337–1392). This trend stimulated writings on Koryŏ and the cultural heritage of Kaesŏng, and led to positive interpretations of the Koryŏ rule.[3] In the late eighteenth century, scholars, such as Yi Tŏk-mu 李德懋 (1741–1793), turned their attention to the Xuanhe fengshi Gaoli tujing 宣和奉使高麗圖經 (Illustrated record of the Xuanhe Emperor’s envoy to Koryŏ) written by Xu Jing 徐兢 (1091–1153), a Chinese envoy who visited Kaesŏng in 1123.[4] Xu Jing commented on the peculiarities and cultural traditions of the Koryŏ people and devoted three chapters to discussions of everyday objects 器皿 (qimin), in particular ceramics and metal wares. Passages of the Gaoli tujing came to be included in writings of the history of the Korean peninsula, such as the Haedong yŏksa 海東繹史 (Unraveled chronicles of East of the Sea), compiled by Han Ch’i-yun 韓致奫 (1765–1814) and his nephew Han Chin-sŏ 韓鎭書 (1777–?). Completed in 1823, the compendium also comprised a chapter on Koryŏ artifacts, mainly celadon ceramics and metalwares. The text was closely based on the Gaoli tujing since few scholars had seen such objects at this time.[5]

It was not until the nineteenth century that Chosŏn scholars wrote about discoveries of Koryŏ artifacts. They include Sŏng Hae-ŭng 成海應 (1760–1839), who mentioned a large celadon jar that was found at the site of An Mun-sŏng’s 安文成 (1262–1346) house in Kaesŏng.[6] In Imha p’ilgi 林下筆記 (Jottings by Imha), Yi Yu-wŏn 李裕元 (1814–1888) wrote about a celadon jar with a cloud pattern that had been unearthed when a Confucian school in Kisŏng 箕城 was repaired.[7] In both instances the celadon wares were found by chance. However, in the late nineteenth century, celadon and other Koryŏ artifacts began to be removed intentionally from tombs. Yi Yu-wŏn noted a case of a man from Kaesŏng who had plundered a royal tomb and sold his loot, a jade belt and several celadon ceramics, for 700 kŭm 金.[8] This event took place in the year kapshin 甲申, corresponding to either 1824 or 1884. Most likely it happened at the latter date, as this was when several reports were published of tombs being looted.[9] The ceramic pieces may have formed part of a set that William R. Carles (1848–1928), the British vice-consul in Seoul, purchased in 1884, and that were said “to have been taken out of some large grave near Songdo [Kaesǒng].”[10]

The widespread plundering of graves, including royal tomb chambers, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is unfortunate, since it led to an irreversible loss of archaeological data that would have otherwise offered significant insight into how people dealt with the dead in practical terms during Koryŏ times. The problem of how to understand Koryŏ mortuary customs is worsened by the fact that the historical sources offer few details. Some aspects of funerary practices are included in the Koryŏsa 高麗史 (History of Koryŏ), such as the repeated reburying of important dead, including King T’aejo太祖 (reigned 918–43), the founder of Koryŏ.[11] However, little information is provided on how the corpse was treated and which types of tomb structures and burial goods were used. It seems that Koryŏ rulers did not specify appropriate means of burial, and the only regulations regarding mortuary practices included in the Koryŏsa concern the size of the exteriors of tombs built for civil and military officials.[12] Similarly, historical sources do not include any discussion of burial goods in terms of which kinds should be used, their numbers, and how they should be placed inside the grave. However, the Koryŏ kings did issue sumptuary laws dictating the use of dress and objects of precious materials. Thus, just as the government regulated the height of the tomb mound according to the social rank of the interred, sumptuary laws are likely to have had a significant impact on the types and numbers of grave goods placed in any one grave. This is reflected in the archaeological material, as will be discussed below.

To date the best-known and most closely examined tombs on the Korean peninsula are those dating to the latter half of the Three Kingdoms period (traditionally 57 BCE–668 CE) when large-scale tomb complexes were built in the kingdoms of Koguryŏ, Paekche, and Silla. Those located in the northern part of the peninsula, then ruled by Koguryŏ (37 BCE–668 CE), have been studied in detail due to their elaborate mural paintings, which provide significant insight into the lives and beliefs of people living in the region. Tombs of the Silla Kingdom (57 BCE–668 CE) have also been the subject of much scholarly interest since they were first discovered during the Japanese colonial period (1910–45) by Japanese archaeologists working for the Government-General of Chōsen [Korea] 朝鮮總督府 (Chōsen Sōtokufu).[13] Located in the Silla capital of Kyŏngju in the southeastern part of the peninsula and believed to be the burial places of Silla rulers and aristocrats, they revealed a huge number and variety of burial goods, ranging from crowns and pieces of jewelry made of gold to ceramics and glass vessels, among many other items. Tombs of the Paekche Kingdom (18 BCE–668 CE) were excavated during the colonial period too, but they came under new scrutiny when in 1971 an intact burial chamber belonging to King Muryŏng 武寧 (reigned 501–23) and his wife was found in Kongju.[14]

Comparatively less is known about mortuary customs of the Unified Silla Kingdom (668–935), and few studies have been published on this topic. From the late seventh century onward, changes occurred in the ways in which members of the elite were buried. This was partially due to the spread of Buddhism, which led to some members of society being cremated. The earliest and best-known example is the burial of King Munmu 文武 (reigned 661–81), who stated on his deathbed that he wished to be cremated and his remains to be buried in an underwater vault in the East Sea, so that he could turn into a dragon and protect Silla from foreign invasions. However, as Sem Vermeersch has pointed out, cremation was not the norm during the Unified Silla period.[15] It was more common for bodies to be interred in tombs of varying shapes and constructions. Members of the royal family usually were buried in small stone chambers covered with soil to form a dome. Some scholars have argued that this construction is an amalgamation of Paekche and Koguryŏ tomb constructions.[16] However, some elements are more akin to Tang dynasty (618–907) Chinese imperial tombs, such as the stone sculptures of officials, warriors, and lions that flank the path leading to the tomb.

Tombs of the Koryŏ elite

In 1916 the first survey of Koryŏ tombs was undertaken. The results were published by the Government-General of Chōsen in a volume that mapped the exteriors, and in some cases the interiors, of around fifty stone chamber tombs 石室墓 (sŏksilmyo) located in the mountains surrounding Kaesŏng. Most of the tombs belonged to members of the royal family and high-ranking officials who were typically interred near the capital.[17] In their basic form and layout, Koryŏ royal tombs carry similarities to Song dynasty (960–1279) Chinese imperial tombs, but they are considerably smaller in scale. A small earthen mound encircled by a stone banister covers the underground tomb. The interior is a single chamber made of stone slabs that are often decorated with mural paintings of secular and Buddhist motifs.[18]

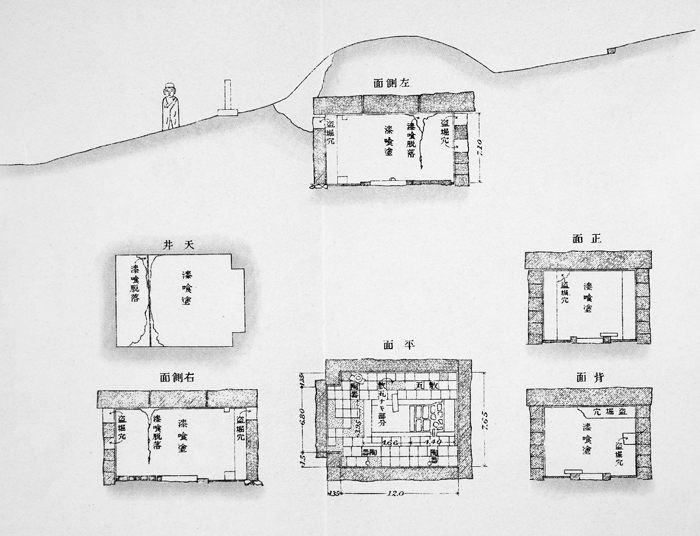

Judging from drawings of the interior of the tomb of King Myŏngjong 明宗 (reigned 1170–87), the center of the chamber had a raised platform measuring 272 cm in length, 118 cm in width, and 20 cm in height on which the coffin was probably placed (fig. 1).[19] The length of the platform suggests that the coffin did not contain cremated remains but an extended body. Despite the prevailing dominance of Buddhism throughout the Koryŏ period, cremation does not seem to have been the custom among those outside the Buddhist clergy.[20] Discoveries of iron nails inside some royal stone chambers indicate that the coffin was made of wood, and historical sources and archaeological evidence indicate that it was decorated with bronze ornaments.[21] Two such gilt-bronze coffin ornaments have been found inside the tomb of Queen Wŏndŏk 元德 (died 1239) (fig. 2).[22] In some cases gilt-bronze appliqué figures of the Four Guardian Animals 四神 (sasin) and/or Buddhist apsaras were also used (fig. 3).[23] They would have been attached to the coffin with nails, as indicated by the nail hole on the body of a gilt-bronze ornament of a dragon that is now in the National Museum of Korea (fig. 4). The fact that representations of the Four Guardian Animals appear alongside Buddhist iconography suggests that it was significant to create a tomb environment that merged different ideologies, reflecting the pluralist nature of Koryŏ worldviews.

In some cases, stone caskets were placed inside tombs. Many carry engraved images of the Four Guardian Animals on either their inner or outer walls, such as one in the Freer Gallery of Art (fig. 5).[24] On other caskets, lotus and apsaras are featured with the Four Guardian animals.[25] Few stone caskets from the Koryŏ period have survived to this day, and unfortunately none have been found in situ, making it difficult to know how they were used and what they originally contained.[26] An epitaph inscription from the mid-twelfth century testifies that in some cases they were used for cremated remains, but in other cases they may have been used to store defleshed bones.[27] There is no archaeological or historical evidence to suggest that burial goods were also placed inside them, but a record by Horace N. Allen (1858–1923) indicates that some did contain artifacts. Sometime between 1894 and 1897, when Allen lived in Seoul, he was asked to go to the police department to view a collection of artifacts that “had been seized from some Japanese who had been caught robbing one of the Royal Tombs near Songdo [Kaesŏng].” Allen noted that the pieces “had been buried in a stone box hewed out of a block of stone with a stone lid attached to the top.”[28] Later in 1907 Allen sent a memo from Seoul to Charles Lang Freer in which he stated, “... it was the custom to bury stone boxes filled with the finest specimens of this high prized [Koryŏ celadon] ware.”[29]

Discussions about what stone caskets originally contained is relevant to our understanding of the arrangement and variety of burial goods placed in royal tombs. By the time archaeologists surveyed the royal stone chambers, grave robbers in search of celadon wares had already looted them; therefore few grave goods were discovered. For this reason it is difficult to ascertain the numbers and types of grave goods that were put in tombs of the elite, not to mention the original locations of the grave goods within the tomb chambers. The diagram of the interior of King Myŏngjong’s tomb shows various kinds of burial goods scattered on the floor (see fig. 1).[30] They include twelve celadon wares, one gilt-bronze ring, and three bronze coins (fig. 6). Although the tomb had been looted, these objects had escaped notice, since earth filtering down through cracks in the roof had gradually covered them.[31] As will be discussed later, the tomb may have contained close to fifty burial artifacts.

Pit Graves

While members of the royal family and high-ranking aristocrats were buried in stone chamber tombs, low-ranking officials, local strongmen 豪族 (hojok), and commoners are believed to have been interred in pit graves. Since the 1980s, hundreds of pit graves have been unearthed, typically as a result of rescue excavations undertaken prior to construction work. Some have been discovered intact, but most have been damaged or looted.[32] Sometimes pits contain bronze coins that carry dates, making it possible to situate the pit within a relatively narrow time frame, but in most cases pit graves are broadly dated within a span of two centuries or more. Some are simply labeled Koryŏ. This makes it difficult to place the burial material within the context of Koryŏ historiography. However, statistical analysis on grave goods found in intact pit tombs suggests that the types of grave goods used did not change much over the course of the Koryŏ Kingdom, but the numbers of bronze and iron artifacts decreased in the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The reason may lie in the invasions and the subsequent conquest of Korea by the Mongols during this time. The Mongol wars had a devastating impact on the country, and the Koryŏ king’s submission to the Yuan (1279–1368) emperor resulted in the peninsula being exploited in various ways. Demands of tribute in the form of gold, silver, and cloth, among other items, were frequent, leaving the country depleted of raw materials, and it seems to have resulted in smaller numbers of metalwares being interred with the dead.[33]

The pit tombs are either in the form of earthen pit graves 土壙墓 (t’okwangmyo) or stone-lined graves 石槨墓 (sŏkkwangmyo). Both types were constructed in the form of rectangular earthen pits, but the latter was further lined with roughly cut stones. Findings of iron nails inside many earthen pits as well as stone-lined graves suggest that bodies were often placed in wooden coffins that have since decayed.[34] The absence of coffin ornaments from pit graves indicates that their use was a privilege reserved for the elite.

Although their construction methods are similar, the graves vary in terms of the types and numbers of objects placed alongside the deceased. To a large extent, this is due to differences in social status. Most pit graves contain no objects at all, but some have yielded celadon ceramics and unglazed stonewares as well as different kinds of metalwares, typically bronze spoons, hairpins, and occasionally mirrors. In some instances, iron scissors have also been found. Judging from the surviving evidence, the types of artifacts put in pit graves are not dissimilar to those placed in tombs of the elite, except in terms of material and quantity. For example, while artifacts made of precious metals like gold and silver have been found in stone chamber tombs, they are seldom recovered from pit graves. Silver spoons, for example, have been unearthed from Koryŏ royal tombs, but never from pit graves, where only bronze spoons have been excavated (fig. 7).[35] Similarly, high-quality celadon wares have been recovered from stone chamber tombs, but only celadon ceramics of lower quality and unglazed stonewares have been unearthed from pit graves.[36]

It is difficult to surmise how the burial goods were laid out in relation to the body since skeletal remains are rarely recovered from pit tombs. Moreover, as the graves do not follow a fixed directional axis, it is not possible to estimate the orientation of the interred body. The most favorable location would depend on the topographical features of the individual burial site as prescribed by geomantic theories, and the directional axis would therefore differ from grave to grave. A well-selected tomb site was believed to have a long-lasting auspicious impact on the welfare of the individual as well as the collective, and it cemented links between the deceased and the descendants.[37]

Burial Goods

Objects that were used as burial offerings in the Koryŏ period can be categorized broadly into the following types: utilitarian goods, jewelry, and weapons. Utilitarian goods include ceramic wares, spoons and chopsticks, metal vessels, and iron scissors. Artifacts classified as jewelry include objects used for personal adornment such as glass, jade and amber beads, metal hairpins, lacquered combs, finger rings, and belts. Weapons constitute the smallest group of objects recovered from graves and are typically in the form of knives. A large number of bronze mirrors have also been unearthed from graves. They seem to have been valued for their auspicious connotations rather than their utilitarian function as reflectors of the human body. In addition to the abovementioned artifacts, a small number of objects of miscellaneous use, such as deer bones and bronze seals, have been excavated from royal tomb chambers and pit graves. Some graves contain bronze coins too, but their role within the burial setting is unclear, and they do not fit into any of the three main types of burial objects mentioned above. It is not possible to present here an in-depth discussion of all kinds of burial goods excavated from Koryŏ graves; therefore the following will focus on core types, such as celadon ceramics and various forms of metalwares.

Ceramics

Ceramic wares are among the most frequently occurring objects in Koryŏ graves. Their shapes, varying from bowls and dishes to cups and jars, are not specifically indicative of ceremonial use. Any organic material they may have contained has decomposed over time, but judging from their positioning within the graves it appears that they functioned purely as mortuary gifts rather than as containers for food offerings. In pit graves it is not uncommon to find some bowls positioned upside down while others have been stacked the right way up, suggesting that no food or liquids were put in the vessels at the time of burial.

Ceramics range in type from celadon wares to unglazed stonewares, and occasionally iron-coated stonewares and porcelaneous wares. Ceramics imported from the Chinese mainland also have been found, predominantly in twelfth-century graves. For example, three white porcelain pieces of Song Chinese make were positioned alongside two locally made celadon wares in the tomb of Mun Kong-yu 文公裕 (died 1159), an official who was in service during the reign of King Injong (fig. 8).[38] The Koryŏ upper classes seem to have also desired wares that looked different from those made on the Korean peninsula, resulting in the import of wares from the Ding, Cizhou, and other kilns in China, especially during the tenth and eleventh centuries, before the local production of celadon reached maturity.[39]

Findings of celadon ceramics in graves are significant since the consumption of high-quality celadon was restricted. Celadon wares produced at the royal kilns at Puan in North Chŏlla Province and at Kangjin in South Chŏlla Province were made for court use. Examples of such high-quality ceramics have been excavated from royal stone chamber tombs around Kaesŏng and on Kanghwa Island, including the tombs of King Injong, King Myŏngjong, Queen Sun’gyŏng 順敬 (died 1236) and Queen Wŏndŏk.[40] It is not known whether kilns produced ceramics that were used solely as burial goods. Lorraine d’O. Warner suggested that the ceramics were buried “fresh from the kiln” as most do not show any signs of use.[41] Still, it is difficult to argue that kilns would produce ceramics specifically for burial. Celadon wares found in tombs are similar in shape, size and design to those excavated from settlement sites, which suggests that there is no difference between burial goods and everyday objects. The same goes for other types of artifacts found in Koryŏ tombs.

Since no royal tombs have been found intact, it is impossible to estimate how many pieces of ceramics were typically interred there. A clue is offered by the aforementioned William Carles, who stated that the celadon wares he purchased had originally formed part of a set of thirty-six.[42] Sir Godfrey Gompertz proposed that the ceramics Carles acquired were looted from the tomb of King Myǒngjong, in which twelve celadon wares were later discovered.[43] If so, the tomb originally would have contained almost fifty pieces of celadon ceramics in addition to other kinds of tomb goods. In contrast, pit graves typically contain fewer numbers of ceramics, and their quality is poorer than those found in stone chambers, as would be expected due to the comparatively lower social rank of the interred. In pit graves, the ceramics were placed next to the head, in other cases, at the feet or elsewhere close to the body of the deceased. Variations in the positioning of ceramics are exemplified in excavated evidence from a large mid- to late twelfth-century burial site at Hyŏn’gongni in Tanyanggun, North Ch’ungch’ŏng Province. The site is unusual since many of the pits reveal well-preserved skeletal remains of the interred. A stone-lined grave contained two celadon ceramics and an unglazed stoneware bottle located close to the head of the deceased. Another piece of celadon ceramic was located close to the right leg. The grave is likely to have belonged to a low-ranking official or a local strongman as suggested by the tomb goods, which, in addition to ceramics, included a bronze mirror and a pair of iron scissors, both of which are associated with people of status (fig. 9). In contrast, in pit no. 23 at the same site, all the grave goods, including five celadon ceramics, were placed at the head of the deceased (fig. 10).[44]

It is not uncommon for graves to contain celadon wares decorated by different types of techniques. In the case of the ceramics found in the stone chamber tomb of Queen Wŏndŏk, some were decorated with sanggam inlay[45] while others carry molded and incised motifs (see fig. 2). Likewise, the ceramics found in the early thirteenth-century tomb of King Myŏngjong range from inlaid wares to wares covered with simple incised patterns. This highlights the difficulties in understanding the chronological evolution of Koryŏ celadon production. Historical sources detailing methods of manufacture are nonexistent, and few wares carry clearly identifiable cyclical dates. It is widely believed that the sanggam technique was perfected in the mid- to late twelfth century. During the thirteenth century, more inlaid wares were made, and sanggam designs became increasingly dense.[46] However, grave finds suggest that earlier types of decorative techniques did not fall out of favor. Instead, members of the royal family appear to have continued to appreciate celadon with simple incised motifs, leading to different types of ceramics being placed inside tombs.

Metalwares

Iron, bronze, silver, and gold artifacts have also been found at grave sites, testifying to their widespread use as burial goods throughout the Koryŏ period. Most surviving objects are of bronze, while those made of silver and gold are relatively rare, undoubtedly because their use was reserved for the elite. Metalwares range in type from utilitarian objects to pieces of jewelry and dress accessories (fig. 11). Utilitarian objects include spoons and chopsticks of bronze or silver, bronze vessels, and bronze and iron scissors (fig. 12). Of those, spoons are the most common, and large numbers of them have survived to this day. Koryŏ spoons were beaten out of flat metal, rather than cast in a mold.[47] They are characterized by their narrow, pointed bowls and curved handles, which are sometimes incised with an abstract swirling design (fig. 8). Most common are those with a curved handle that splits into a jagged fishtail design. Other spoons feature a small lotus bud that sits at the end of the handle, signifying the impact of Buddhism at this time. Folding spoons were also made. On some, as in a piece from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the handle has a loose closing ring, allowing it to retract (see fig. 13). During the fourteenth century, the pointed bowl and tail design gradually fell out of favor and were replaced by simpler shapes that are characteristic of spoons manufactured during the Chosŏn period. Chosŏn spoons tend to have rounded bowls and handles that gradually widen and end in a triangular shape.

Pit graves typically contain spoons made of bronze, sometimes accompanied by a set of bronze chopsticks, but spoons of silver have been unearthed from royal tomb chambers, as already mentioned. Occasionally, members of the royal family were buried with celadon ceramic spoons. They are extremely rare, but one example is now in the collection of the National Museum of Korea (fig. 14). In size and shape, the celadon spoon is similar to bronze spoons with shallow, pointed bowls and curved handles. However, the bowl of the celadon spoon has an unusual decoration: an incised motif of a dragon chasing a flaming pearl.

Archaeological finds indicate that no more than one spoon was placed in any one grave, suggesting that the spoon was likely to have been used by the deceased during his or her lifetime and that it was customary to pair spoons with their owners for eternity. When found in pit graves in which ceramic wares were also buried, the spoon is often located next to the ceramics, indicating a link between these two types of grave goods, through associations with food. Spoons have also been excavated on the Chinese mainland from graves dating to the Song, Liao (907–1125), Jin (1115–1234), and Yuan dynasties. Chŏng Ŭi-do has argued that the use of spoons as burial goods entered Koryŏ directly from Liao China, where this tradition seems to have been particularly widespread.[48] However, that the custom of placing spoons in graves may have been a local, rather than a foreign, tradition should not be ruled out. Bronze spoons have been found at several tomb sites from the Silla and Paekche Kingdoms, including the tomb of King Muryŏng, in which three bronze spoons and two sets of bronze chopsticks were found.[49]

Bronze vessels and scissors have been excavated in comparatively smaller numbers than spoons. Vessels are typically in the form of wide-shouldered or pear-shaped bottles. Some were cast, but others were spun by mounting a small bronze cylinder on a lathe-like device and drawing the malleable metal out to its final shape while it rotated at high speed. This technique permitted thinner walls, making vessels lighter and requiring smaller amounts of bronze. Typical of spun bottles are the concentric lines that appear on the body. Pear-shaped bottles tend to have been made in several sections, which were brazed together, resulting in raised lines on the surface, as seen on a bottle in the Freer Gallery (fig. 15). Although the technique of inlaying bronze wares with gold or silver wire was popular during the Koryŏ period, its use seems to have been reserved for the elite, since only plain bronze wares have been excavated from pit graves, where they tend to be placed alongside ceramic wares, signifying their utilitarian function.[50]

Scissors were made of either bronze or iron. No scissors have been found in stone chamber tombs, but several iron examples have been excavated from pit graves dating from between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, suggesting their continuous use as burial goods. Some scissors resemble their twenty-first-century counterparts in that they have rings for the thumb and index finger, and the pivoted blades are held together with a nail (fig. 16).[51] Others bear closer resemblance to shears in that they are in the form of a simple loop and have no rings for the fingers, as in the case of iron scissors excavated from an eleventh-century stone-lined grave at Chibongni in Yŏngdonggun, North Ch’ungch’ŏng Province (fig. 17).[52] Its location on top of a bronze mirror is not unusual, and it has led some scholars to make gendered links between scissors and mirrors, arguing that scissors were used for sewing and mirrors for vanity, and therefore both types of objects should be associated with women. However, there is little evidence so far to support this theory. Due to the common absence of skeletal remains in pit graves, it is rarely possible to identify the gender of the interred. Moreover, several scissors have been excavated from graves that did not contain mirrors.[53]

Various pieces of jewelry and dress accessories have been unearthed from Koryŏ graves, and they include hairpins and openwork ornaments made of bronze, silver, or gold as well as finger rings and belts. Hairpins are the most frequently encountered type of jewelry, and they have been excavated from royal tombs as well as pit graves, suggesting their widespread use among different social classes. Men are believed to have used pins with two short legs and flat or domed heads to wind their hair into topknots. Therefore, they are usually referred to as topknot pins 銅串 (tonggot). Due to a lack of archaeological evidence, it is difficult to verify such gendered interpretations, and two topknot pins were excavated from the previously mentioned tomb of Queen Wŏndŏk, indicating that women also may have used them (see fig. 2). Many topknot pins have a simple u-shape (fig. 18). On others, the domed head is of solid metal. It is not uncommon for pit graves to contain only one topknot pin and no other burial goods. In such cases, the pin typically is located at the end of the pit where the head would have rested, suggesting that the deceased wore it at the time of burial.[54]

Topknot pins were made of gold, silver, or bronze and often were gilded. Differences in their manufacture and material likely indicate the social status of the interred. Some are elaborately decorated with repoussé patterns, often in the form of rosettes resembling lotus flowers, as seen on a gilt-bronze pin now in the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 19). A virtually identical piece in silver-gilt is in the British Museum.[55] Repoussé decorations were created by pressing and hammering a thin sheet of metal against a raised design, so that the metal retained the shape of the design. Afterward, details were added by incising the metal.[56] Repoussé objects are thought to have been made between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, suggesting that the V&A hairpin dates to this time.

During the Koryŏ period, bronze mirrors also formed an integral part of the burial assemblage. In daily life, mirrors were used as reflectors of the human body, but the archaeological record indicates that the people of Koryŏ, unlike the Chinese, did not place mirrors in graves because of their perceived ability to reflect light. Nor were burial mirrors associated with their secular uses as vanity objects. Rather, mirrors were broadly regarded as auspicious artifacts associated with high social status, and thus contributed favorably to the burial setting.[57] That mirrors did not have a clearly prescribed function within the burial setting is indicated by the fact that they are found with their reflective surfaces facing either upward or downward, and they are just as likely to be found in the middle as at either end of a grave.

No mirrors have been excavated from stone chamber tombs, but reports from the early twentieth century make mention of mirrors being unearthed from graves alongside celadon wares, bronze vessels, and articles of jewelry.[58] This suggests that mirrors may have been among the many objects that were looted from royal stone chamber tombs near Kaesŏng at this time. In pit graves they tend to be found with a relatively large number and variety of burial goods, suggesting that the graves belonged to low-ranking officials or local strongmen rather than commoners. Unfortunately it is impossible to know how many mirrors were typically interred in royal tombs, but no more than one mirror has been excavated from any one pit grave.

Koryŏ mirrors were cast in a wide spectrum of sizes and shapes, such as circles, squares, flowers, clouds, and bells. In contrast to earlier times, when mirrors chiefly carried cosmological motifs, during the Koryŏ period various kinds of patterns became popular. These included pictorial subject matters as well as stylized flower, bird, and animal patterns, all of which carried auspicious messages of longevity, benevolence, and harmony. Some of the largest and heaviest mirrors made during this time feature a central pattern of two dragons chasing flaming pearls (fig. 20). Traditionally, the use of dragon motifs was not available to all but was reserved for the royal family since, in accordance with Chinese custom, it denoted power and authority. For example, ceramics with dragon motifs largely appear on high-quality wares produced at the royal kilns in Puan and Kangjin.[59] In the case of mirrors, their size and skillfully cast dragon designs suggest they were made for an exclusive clientele who could afford them and were allowed to use extravagant items. Several mirrors of the type illustrated here are now housed in the National Museum of Korea. Acquisition records indicate that they were found near Kaesŏng, suggesting that they may have come from the royal and aristocratic tombs located in this area. Before they were placed in graves, they may have been used as secular objects in upper-class homes.

Continuation and Change in the Late Koryŏ and Early Chosŏn Periods

Toward the end of the Koryŏ period changes took place in terms of how the dead were interred. This was largely due to the rising interest in Neo-Confucian philosophy following the introduction to Koryŏ of the Jia li 家禮 (Family Rituals) written by the Song Chinese Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200).[60] In the new kingdom of Chosŏn, Zhu Xi’s writings became extremely influential. By the 1420s Confucian scholars were arguing that the Jia li should be the exclusive manual for funeral and mourning rites, resulting in significantly different ways of dealing with the dead.[61] Among other aspects, it led to the construction of new types of tombs and to the production and use of tomb goods that were entirely different in style and manufacture to those of Koryŏ times. However, old habits die hard, and the uncivilized, un-Confucian ways in which people continued to dispose of the dead were a source of much frustration for the government.[62] Despite the Neo-Confucian scholars’ disdain of Koryŏ ways of burial and their insistence on conducting rituals according to Zhu Xi’s writings, it took centuries before all aspects of the Jia li were observed. Instead, people of the late Koryŏ and early Chosŏn periods seem to have adopted a selective approach to the manual’s instructions by following only some of them. As I have discussed the rise of Confucian ways of interment during this period in an earlier paper, here I will highlight only key facets of this issue.[63]

Archaeological evidence suggests that instructions on preparing the burial pit were among the first aspects of the manual to gain acceptance on the peninsula. To protect and safeguard the bones of the deceased, Zhu Xi recommended that burial pits be lined with charcoal and a thick layer of cement. The earliest examples of such graves date to the fourteenth century, and include one excavated at Songnari in Hwasŏnggun, Kyŏnggi Province.[64] Over the past ten to fifteen years, an increasing number of cement-lined graves from the Chosŏn Kingdom have been excavated, resulting in our better understanding of burial practices from this period. Among the earliest cement-lined graves from the opening decades of the Chosŏn rule are the tombs of Il Sŏn-mun 一善文, wife of Yi Myŏng-chŏng 李命貞 (1504–1556), and Yi Ŭng-t’ae 李應台 (1556–1586), both located in Chŏngsang-dong in Andong, North Kyŏngsang Province.[65]

Several graves of the early Chosŏn period—earthen-pit as well as cement-lined ones—contain burial goods similar to those of the late Koryŏ period, including ceramic vessels, bronze spoons, and iron scissors. However, the use of normal-sized objects waned over time in favor of miniature-sized versions. Zhu Xi argued that treating the dead as if they were alive was arrogant and therefore discouraged the use of normal-sized burial goods. Instead he advised that grave goods “should resemble those used in real life but be smaller.” [66] This gave rise to the manufacture and use of myŏnggi 明器 (literally “spirit objects”), which are objects made specifically for burial. They are of incomplete shape, of the “wrong” material, and/or made in miniature. The appropriate materials, sizes, and shapes of myŏnggi were already standardized during the first decades of the Chosŏn rule.[67] Myŏnggi usually were made of porcelain, although some examples of punch’ŏng stoneware also exist from the sixteenth century. Most porcelain myŏnggi have rough forms and plain, undecorated surfaces (fig. 21). However, some members of the royal family, such as Royal Concubine Wŏnbin元嬪 (1766–1779), were interred with myŏnggi of finely potted porcelain, decorated with underglaze pigments of cobalt, iron, or copper (fig. 22).[68]

Changes also happened to the ways in which burial goods were arranged inside tombs. In accordance with Zhu Xi’s instructions, they were placed in small niches carved into the pit wall. He offered the following guidelines: “When the soil is filled halfway up [the burial pit], store the grave goods [and other furnishings] in side niches. Block their entrances with board.”[69] Though such niches were not always used, they became increasingly common over the course of the Chosŏn period, as reflected in a sixteenth-century grave at Sawŏlli in South Kyŏngsang Province where several miniature porcelain vessels and other goods were placed in two niches carved into the pit wall (fig. 23).[70] By this time Confucian means of interment were well established in Korea, certainly among the elite, and the Jia li was increasingly adhered to as a manual for burial.

Conclusion

The study of Koryŏ mortuary practices is an evolving field, and much still needs to be understood. Broadly speaking, it can be argued that diversity and variability characterize Koryŏ funerary customs. This is partially attributed to the fact that burials were governed by varied worldviews, including Buddhist and geomantic beliefs, which influenced the burial setting in different ways. But more important, Koryŏ rulers did not lay down rules about how people should be buried. Differences in social status established some parameters for how funerals should be carried out, but overall people were largely free to deal with the dead as they saw fit. As a result, bodies were disposed of in a variety of ways, ranging from cremation to burial in wooden coffins, placed either in stone chambers or in pit graves. Similarly, there were no clear rules about which types and how many burial goods should be interred with the deceased or how they should be located within the graves.

Nevertheless, through detailed examination of the material record, certain patterns and shared concerns become apparent. The need to uphold a relationship with the dead was deemed important, as is reflected, for example, in the significance attached to the selection of burial sites according to geomantic theories. In the same way, the interment of burial artifacts served predominantly as a final act of respect paid to the deceased by his or her descendants. Through the gifting of such goods, the living did not just consolidate their relations to the dead; by placing high-value objects in the tomb, they visually formalized in a public way the social standing and wealth of the deceased and his or her kin group. Therefore, the act of burying the dead with grave goods served to cement and eternalize links between the dead and the living.

The forging and maintenance of strong bonds between the dead and the living became extremely important during the Chosŏn period due to the Neo-Confucian emphasis on ancestral worship. However, regulatory measures that were put in place from the fifteenth century onward with the aim to ensure that funerals were conducted appropriately marked a considerable shift in mortuary practices and led to standardized ways of dealing with the dead, including the manufacture of artifacts used exclusively for burial.

Notes

See, among others: Randolph I. Geare, “The Potter’s Art in Korea,” The Craftsman 7, no. 3 (December 1904), 297; John Platt, “Ancient Korean tomb wares,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 22, no. 116 (November 1912); Lorraine D’O. Warner, “Korean Grave Pottery of the Korai Dynasty,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 6, no. 3 (April 1919); William B. Honey, Corean Pottery (London: Faber and Faber, 1947), 3.

For examples and further discussion, see Charlotte Horlyck, “Desirable Commodities—Unearthing and Collecting Koryŏ Celadon Ceramics in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 76, no. 3 (2013), 476–77.

Chang Nam-wŏn 장남원, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk ŭi hyŏngsŏng kwajŏng ŭro pon Chosŏn hugi ŭi chŏnghwang” 고려청자에 대한 기억의 형성과정으로 본 조선후기의 정황 (The establishment of social memory of Koryŏ celadon in the late Chosŏn period), Misulsa nondan 28 (2009), 163.

Chang Nam-wŏn, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk,” 163–64.

Chang Nam-wŏn, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk,” 150.

An Mun-sŏng was a well-known scholar of the Koryŏ period. Sŏng Hae-ŭng notes that the height of the jar was around thirty centimeters 一尺 (il ch’ŏk), and that it could contain around eighteen liters 一斗 (il tu). Sŏng Hae-ŭng, “An Mun-sŏng chajun’gi” 安文成瓷尊記 (Essay on An Mun-sŏng’s ceramic jar), Yŏn’gyŏngjae chŏnjip 硏經齋全集 (Collected works of Yŏn’gyŏngjae), kwŏn 9. Cited in Chang Nam-wŏn, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk,” 152. Yŏn’gyŏngjae chŏnjip is thought to have been published in 1840.

The location of Kisŏng is not clear from the context. Kisŏng is an old name for Pyongyang, but it is also a city near Ulchin in North Kyŏngsang Province. Yi Yu-wŏn, “Chagi koje” 瓷器古製 (Old ceramics), Imha p’ilgi, kwŏn 29. See also Chang Nam-wŏn, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk,” 154.

Yi Yu-wŏn, “Pyŏngnyŏ shinji” 薜茘新志 (New additions by a hermit), Imha p’ilgi, kwŏn 35. See also Chang Nam-wŏn, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk,” 159–60.

Chang Nam-wŏn argues that the incident happened in 1824, but there is no evidence to support such an early date. Chang Nam-wŏn, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja e taehan sahoejŏk kiŏk,” 159–60. For a discussion of early discoveries of Koryŏ celadon, see Horlyck, “Desirable Commodities,” 477–78.

William R. Carles, Life in Corea (London: MacMillan and Co., 1888), 139.

After his death, T’aejo was initially buried in Hyŏnnŭng tomb 顯陵 near Kaesŏng, but his bones were moved several times until 1276 in order to safeguard them during times of invasions and unrest. Charlotte Horlyck, “Ways of Burial in Koryŏ Times,” in Death, Mourning, and the Afterlife in Korea: Critical Aspects of Death from Ancient to Contemporary Times, ed. Charlotte Horlyck and Michael Pettid (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2014), 90–91.

These were fixed by law in the late tenth century during the first year of the reign of King Kyŏngjong 景宗 (reigned 975–81). Koryŏsa 85: 6b.

The first surveys of Silla tombs were led by the scholar and archaeologist Ryū Imanishi 今西龍 (1875–1932) who in 1906 carried out surveys of tombs located near Sogŭmgang Mountain in Kyŏngju. Symposium on “Silla kobun palgul chosa 100 nyŏn” 신라고분 발굴 조사 100년 (100 years of Silla excavations), Cultural Heritage Administration, http://www.cha.go.kr/newsBbz/selectNewsBbzView.do?newsItemId=155158350§ionId=b_sec_1 (accessed July 24, 2013).

For an overview of tomb material of the Three Kingdoms period, see Kang In-gu 강인구, Kobun yŏn’gu 고분 연구 (Seoul: Hakyŏn munhwasa, 2000), 11–630.

Sem Vermeersch, “Death and Burial in Medieval Korea: The Buddhist Legacy,” in Death, mourning, and the afterlife in Korea.

Chŏng Chong-su 정종수, “Uri nara myoje” 우리나라墓制 (Korea’s funerary customs), in Yŏngwŏnhan mannam Han’guk sangjangnae 영원한 만남 韓國喪葬禮 (Eternal Beauty. Korean Funeral Customs), ed. Kungnip minsok pangmulgwan 國立民俗博物館 (Seoul: Mijinsa, 1990), 134.

The volume lists the locations of the tombs, their precincts, tomb statues, and grave goods. Chōsen Sōtokufu朝鮮総督府, Taishō 5-Nendo Koseki Chōsa Hōkoku大正五年度古蹟調査報告 (1916 Report on Investigations of Historic Remains) (Keijō [Seoul]: Chōsen Sōtokufu, 1916). For recent images of the tombs, see Chang Kyŏng-hŭi 장경희, Koryŏ wangnŭng 고려 왕릉 (Koryŏ royal tombs) (Seoul: Yemaek, 2008).

Since most of the royal tomb chambers are located near Kaesŏng in North Korea, it is difficult to visit them, and only few studies have been carried out on their interior design and decoration. For a discussion of the murals in the tomb of King T’aejo, see Chu Chae-gŏl 주재걸, “Koryŏ T’aejo wangnŭng ŭi pyŏkhwa wa sam-u e taehayŏ” 고려 태조 왕릉의 벽화 와 삼우에 대하여 (About the wall paintings and the Three Friends of Koryŏ T’aejo’s royal tomb), Minjok munhwa yusan 2 (2004). For an examination of the murals inside the tomb of King Kongmin 恭愍 (reigned 1351–74), see Chǒng Pyǒng-mo정병모, “Kongmin wangnŭng ŭi pyǒkhwa e taehan koch’al” 공민왕릉의 벽화에 대한 고찰, Kangjwa misulsa 17 (2001). Some Koryŏ tomb chambers with murals have been excavated in South Korea. Unfortunately none of the tombs were in an intact state, and only few burial goods were recovered. For an overview of the iconography of the murals, see Munhwajae kwalliguk and Munhwajae yŏn’guso文化財管理局, 文化財硏究所, P’aju Sŏgongni Koryŏ pyŏkhwamyo chosa pogosŏ坡州 瑞谷理 高麗 壁畫墓 發掘調査 報告書 (Excavation report of a Koryŏ tomb with murals at P’aju Sŏgongni) (Seoul: Munhwajae kwalliguk, Munhwajae yŏn’guso, 1993), 118. In 2000, a tomb with well-preserved mural paintings was excavated in Kobŏmni near Miryang, South Kyŏngsang Province. The interred was the scholar-official Pak Ik 朴翊 (1332–1398), and the tomb is believed to be representative of late Koryŏ burial structures. Shim Bong-gŭn 심봉근, Miryang Kobŏmni pyŏkhwamyo 密陽古法里 壁畵墓 (Mural tomb at Miryang Kobŏmni ) (Pusan: Sejong ch’ulp’ansa 2003). See also Horlyck, “Ways of burial,” 94–96.

Chōsen Sōtokufu, Taishō 5-Nendo, 501–8; Chang Kyŏng-hŭi, Koryŏ wangnŭng, 63.

In this way Koryŏ differed from Song and Yuan China, where cremation was more widespread. See Patricia Ebrey, “Cremation in Sung China,” The American Historical Review 95, no. 2 (1990). For a discussion of cremation in Koryŏ, see Vermeersch, “Death and Burial in Medieval Korea,” 38–47.

An entry in the T’aejong sillok 太宗實錄 (Annals of T’aejong) states that in Koryŏ the coffin was at times covered with gold ornamentation. Martina Deuchler, The Confucian Transformation of Korea: A Study of Society and Ideology (Cambridge, MA: Council of East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1992), 77.

Queen Wŏndŏk was the wife of King Kangjong 康宗 (reigned 1211–13). She was buried on Kanghwa Island, where the royal capital was moved in 1232 due to the Mongol invasions of the Korean peninsula. For a discussion of the tomb, see Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan 국립중앙박물관, Koryŏ wangsil ŭi tojagi 고려 왕실의 도자기 (Royal ceramics of the Koryŏ Kingdom) (Seoul: T’ongch’ŏn munhwasa, 2008), 38–39.

Several gilt-bronze coffin ornaments are in the collection of the National Museum of Korea. They are illustrated in Hoam misulgwan 湖巖美術館, Tae Koryŏ kukpojŏn: widaehan munhwa yusan ŭl ch’ajasŏ (1) 大高麗國寶展 – 위대한문화유산을찾아서 (1) (The Great Koryŏ exhibition: In search of a cultural legacy [1]) (Seoul: Samsŏng munhwa chaedan, 1995), figs. 276–82.

The casket was purchased by Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) from Yamanaka and Co. in Osaka in 1909. Korean Art in the Freer and Sackler Galleries (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2012), 138–39.

For caskets in the collection of the National Museum of Korea, see Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan 국립중앙박물관, Koryŏ myŏjimyŏng 高麗墓誌銘 (Koryŏ epitaphs) (Seoul: Kungnip chungang pangmulgan, 2006). A small number of caskets are also in Western collections. In addition to the one in the Freer and Sackler Galleries, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (accession number A. 117-1918) and the Arts Institute of Chicago (accession number 1927.553) each have one.

Chŏng Kil-cha 鄭吉子, “Koryŏ kwijŏk ŭi choripsik sŏkkwan kwa kŭ sŏn’gakhwa yŏn’gu” 高麗 貴族의 組立式 石棺과 그線刻畵 硏究 (Study on stone coffins of the aristocracy and their engraved designs), Yŏksa hakpo 108 (1985).

Horace N. Allen. Copy of A Certified Catalogue of a Collection of Ancient Corean Pottery Purchased and Owned by Horace Newton Allen (Nak Tong: The Seoul Press, 1901), 6. Quoted in Korean Art, 139–40.

Freer|Sackler Archives. Quoted in Korean Art, 140. This view was shared by Lorraine D’O. Warner who noted “as the Koreans customarily used coffins made of stone slabs, the pottery was well protected.” Lorraine D’O. Warner, “Kōrai Celadon in America,” Eastern Art: An Annual 2 (1930), 69.

Godfrey St. G. M. Gompertz, Korean Celadon and Other Wares of the Koryŏ Period (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), 22.

Excavation reports of Koryŏ tombs are too numerous to list here. Large-scale sites include: Hanyang taehakkyo pangmulgwan 漢陽大學校博物館, Koyang Chungsan chigu munhwa yujŏk palgul pogosŏ 高陽 中山地區 文化遺蹟 發掘調査報告書 (Excavation report of cultural remains from the region of Chungsan, Koyang) (Kyŏnggido: Hanyang taehakkyo, 1993); Han’guk munhwajae poho chaedan 韓國文化財保護財團 and Munhwajae chosa yŏn’gudan 文化財調査硏究團, Ch’ŏngju Yongam yujŏk (I) 淸州 龍岩遺蹟 (I) (Remains from Ch’ŏngju Yongam (I)) (Seoul: Han’guk munhwajae poho chaedan, 2000); Han’guk munhwajae poho chaedan 韓國文化財保護財團 and Munhwajae chosa yŏn’gudan 文化財調査硏究團, Ch’ŏngju Yongam yujŏk (II) 淸州 龍岩遺蹟 (II) (Remains from Ch’ŏngju Yongam [II]) (Seoul: Han’guk munhwajae poho chaedan 韓國文化財保護財團, 2000); Wŏngwang taehakkyo mahan paekche munhwa yŏn’guso 圓光大學校 馬韓百濟文化硏究所, Such’ŏnni Koryŏ kobun’gun 壽川里高麗古墳群 (Koryŏ graves at Such’ŏnni) (Seoul: Wŏngwang taehakkyo mahan paekche munhwa yŏn’guso, 2001); Hanyang taehakkyo pangmulgwan 한양대학교박물관, Ansan Taebudo Yukkok Koryŏ kobun’gun palgul chosa pogosŏ 安山大阜島 六谷 高麗古墳群 發掘調査報告書 (Excavation report of Koryŏ tombs at Yukkok, Taebudo, Ansan) (Seoul: Hanyang taehakkyo pangmulgwan 2002); Kyŏnggido pangmulgwan 京畿道博物館, Ansŏng Maesanni Koryŏ kobun’gun palgul chosa pogosŏ 安城 梅山里 高麗 古墳群 發掘調査報告書 (Excavation report of Koryŏ tombs at Maesanni, Ansŏng) (Yongin: Kyŏnggido pangmulgwan, 2006); Han’guk munhwajae poho chedan 韓國文化材保護財團, Inch’ŏn Wŏndangdong yujŏk (I) 仁川 元堂洞 遺蹟 (I) (Remains from Inch’ŏn Wŏndangdong (I)) (2007: Seoul: Han’guk munhwajae poho chaedan).

For a comparison of grave goods found in early and late Koryŏ pit graves, see Charlotte Horlyck, “Mirrors in Koryŏ Society: Their History, Use and Meanings” (PhD diss., SOAS, University of London, 2006), 140–43.

A silver spoon and a set of silver chopsticks were excavated from a stone chamber tomb near Kaesŏng believed to have belonged to King Injong 仁宗 (reigned 1122–46). Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan, Koryŏ wangsil ŭi tojagi, 18.

Yi Mong-il 이몽일, Han’guk p’ungsu sasangsa한국풍수사상사 (The history of Korean geomantic thought) (Seoul: Myŏngbo munhwasa, 1991), 119.

Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan 국립중앙박물관, Ch’ŏnha cheil pisaek ch’ŏngja 천하제일 비색청자 (The best under heaven, the celadons of Korea) (Seoul: Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan, 2012), 134–37.

Kim Yŏng-wŏn 김영원, “Han’guk kwa chungguk ŭi toja kyoryu, 10–19 segi” 한국과 중국의 도자 교류, 10–19세기(Korean-Chinese ceramic exchanges during Koryŏ and Chosŏn) in Chungguk toja 중국 도자 (Chinese ceramics), ed. Kungnip chungang pangmulgan 국립중앙박물관 (Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2007), 32–35.

The ceramics are discussed and illustrated in Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan, Koryŏ wangsil ŭi tojagi, 17–42.

Sŏul sirip taehakkyo pangmulgwan 서울시립대학교박물관, Tanyang Hyŏn’gongni Koryŏ kobun’gun 丹陽 玄谷里 高麗 古墳群 (Koryŏ tombs at Hyŏn’gongni, Tanyang) (Seoul: Sŏul sirip taehakkyo pangmulgwan, 2008), 5, 78–85, 150–59.

Sanggam refers to the technique of inlaying incised patterns with either white or red slip. When dry, excess slip was scraped off to ensure that only the incised patterns were filled in. Thereafter the ceramic ware was biscuit fired, glazed, and fired again. After firing, the white slip remained white, while the red slip turned black due to its high iron content.

Kim Jae-yeol, “Goryeo Celadon,” in Goryeo Dynasty: Korea’s Age of Enlightenment, 918–1392, ed. Kumja Paik Kim (San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, 2003), 237.

L. W., “Korean Bronze Spoons of the Korai Dynasty,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 4, no. 6 (1917), 100.

Chŏng Ŭi-do 정의도, “Song Yo Kŭm Wŏn myo sijŏ mit ch’ŏllae ch’ult’o kyŏnghyang” 宋遼金元墓 匙箸 및 鐵錸 出土 傾向 (Spoons and iron scissors found in Song, Liao, Jin, and Yuan tombs), Munmul yŏn’gu 15 (2009), 69–74.

For spoons found at Three Kingdoms tomb sites, see Chŏng Ŭi-do 정의도, “Ch’ŏngdong sutgarak ŭi tŭngjang kwa hwaksan” 靑銅 숫가락의 登場과 壙散 (The appearance and diffusion of bronze spoons), Sŏktang nonch’ong 42 (2008), 279–94.

For examples of the locations of bronze vessels in pit graves, see the report of an excavation of a large burial site at Kŭmch’ŏndong in Ch’ŏngju, North Ch’ungch’ŏng Province dating from the late eleventh to the twelfth century. Han’guk munhwajae poho chaedan and Munhwajae chosa yŏn’gudan, Ch’ŏngju Yongam yujŏk (II).

For comparative examples, see Ewha yŏja taehakkyo pangmulgwan 이화여자대학교박물관, Han’guk ŭi kŭmsok misul 한국의 금속미술 (Metal art in Korea) (Seoul: Ewha yŏja taehakkyo pangmulgwan, 2009), 98.

Hannam taehakkyo pangmulgwan 韓南大學校博物館, Yŏngdong Chibongni kobun palgul chosa pogo 永同 池鳳里 古墳 發掘調査報告 (Excavation report of graves at Chibongni, Yŏngdong) (Seoul: Hannam taehakkyo pangmulgwan, 1987), 20.

For a discussion of the locations of hairpins in pit graves, see Horlyck, “Mirrors in Koryŏ Society,” 572–76.

The accession number of the British Museum hairpin is OA+.107. For a discussion, see Charlotte Horlyck, “Goryeo Metalwork in the British Museum,” Orientations 41, no. 8 (November/December 2010), 70.

Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Kŭmŭn pohwa: Han’guk chŏnt’ong kongye ŭi mi 금은보화. 한국 전통공예의 미 (Opulence: Treasures of Korean traditional craft) (Seoul: Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, 2012), 170.

See, for example, Mrs. Langdon Warner, “Grave Pottery of the Korai Dynasty,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 16, no. 61 (1918), 17.

Yi Chong-min 李鍾玟, “Koryŏ ch’ŏngja yong changshik ŭi yangshikchŏk kyebo wa p’yŏnnyŏn” 高麗靑磁 龍 裝飾의 樣式的 系譜와 編年 (The stylistic evolution and chronology of decorations of dragons on Koryŏ celadon), Yŏksa wa tamnon 53 (2009), 338.

For a discussion of the introduction of the Jia li to Koryŏ, see Kojima Tsuyoshi, Sadaebu ŭi sidae (The period of the literati class) (Seoul: Tongasia, 2007), 96–101.

Boudewijn Walraven, “Popular Religion in a Confucianized Society,” in Culture and the State in Late Choson Korea, ed. JaHyun Kim Haboush and Martina Deuchler (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Asia Center, 1999).

Charlotte Horlyck, “Confucian Burial Practices in the Late Goryeo and Early Joseon Periods,” The Review of Korean Studies 11, no. 2 (2008).

Yun Se-yŏng 尹世英 and Kim U-rim 金右臨. “Hwasŏng Songnari kobun’gun palgul chosa pogo’ 華城 松羅里 墳墓群 發掘調査報告 (Excavation report of the burial site at Hwasŏng Songnari),” in Sŏhaean kosoktoro kŏnsŏlgugan (Ansan – Anjunggan) yujŏk palgul chosa pogosŏ 서해안 고속도로 건설구간 (안산-안중간) 유적 발굴 조사 보고서 (2) (Excavation report of archaeological remains excavated during the construction of the Sŏhaean express way [2]), ed. Tan’guk taehakkyo chungang pangmulgwan 단국대학교물관 (Seoul: Tan’guk taehakkyo chungang pangmulgwan, 1995). See also Horlyck, “Confucian Burial Practices.”

Im Se-kwŏn 임세권 and Kwŏn Tu-gyu 권두규, “Il Sŏn-mun Ssi wa Yi Ŭng-t’ae myo ŭi kujo” 일선문씨와 이응태 묘의 구조 (The structure of the tombs of Il Sŏn-mun and in Yi Ŭng-t’ae), in Andong Chŏngsangdong Il Sŏn-mun Ssi wa Yi Ŭng-t’ae myo palgul chosa pogosŏ 안동 정상동 일선문씨와 이응태 묘 발굴조사 보고서 (Excavation report of the tombs of Il Sŏn-mun Ssi and Yi Ŭng-t’ae in Andong Chŏngsangdong), ed. Andong taehakkyo pangmulgwan 안동대학교박물관 (Andong: Andong taehakkyo pangmulgwan, 2000).

Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Chu Hsi’s Family Rituals (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 109, 121–22.

For a diagram detailing the types of myŏnggi specified in the Sejong sillok 世宗實錄, see Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan 국립중앙박물관, Paekcha hangari, Chosŏn ŭi in kwa ye rŭl tamda 백자항아리, 조선의 仁과 禮 를 담다 (White porcelain jars, encompassing Chosŏn virtue and rituals) (Seoul: Kungnip chungang pangmulgan, 2010), 49.

For further examples of myŏnggi excavated from royal graves, see Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan, Paekcha hangari, 50–53. For examples of lower-quality myŏnggi, see Charlotte Horlyck, “Korean Art Objects at SOAS,” in Key Papers on Korea: Papers Celebrating 25 Years of the Centre of Korean Studies, SOAS, University of London, ed. Andrew Jackson (Boston: Global Oriental/ Brill, 2013), 279–81.

Han’guk taehakkyo pangmulgwan hyŏphoe 韓國大學校博物館協會, Sin palgul maejang munhwajae torok 新發掘 埋藏 文化財圖錄 (Cultural property record of recently excavated burials) (Seoul: Han’guk taehakkyo pangmulgwan hyŏphoe, 1997), 140–42.

Ars Orientalis Volume 44

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0044.009

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.