- Volume 44 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

Abstract

The Eastern Han mural tomb at Horinger often is said to feature one of the earliest Buddhist themes in China, namely, the relics of the Buddha or a related motif. But the controversial basis for such identification, the tomb’s now-vanished inscription of “shēlì 猞猁,” resulted from an unverifiable reading by a local archaeologist working under adverse conditions and an unqualified confirmation by a leading authority in the discipline—neither of whom were specialists in Buddhism. There is nothing in the tomb that justifies connecting it to the Sanskrit term śarīra, a reference to the Buddha’s cremated remains. This essay offers insight into the critical problems that arise when art historical misidentifications are cited in general historical treatments, thus distorting the picture of early Buddhism and its material culture in China.

Introduction

The introduction of Buddhism from India around the first century CE contributed to one of the most groundbreaking transformations of visual art and religious practice in China. Since Yu Weichao’s 俞偉超 (1933–2003) influential 1980 study, several tombs dating to the Eastern Han 漢 period (25–220) have been said to feature such “Buddhist” themes.[1] Despite a few isolated traits, however, these tombs generally lack a broader Buddhist context. And because the tombs are part of an ancient native tradition of mortuary art, scholars typically have been reluctant to highlight strong Buddhist traits within them. Examples usually were labeled as Buddhist-Chinese hybrids or Chinese adaptations of Buddhist motifs.[2] I believe this caution was justified, and concur in principle with the seminal analysis of such Buddhist-related motifs made by Wu Hung [Hong 巫鴻] in 1986.[3]

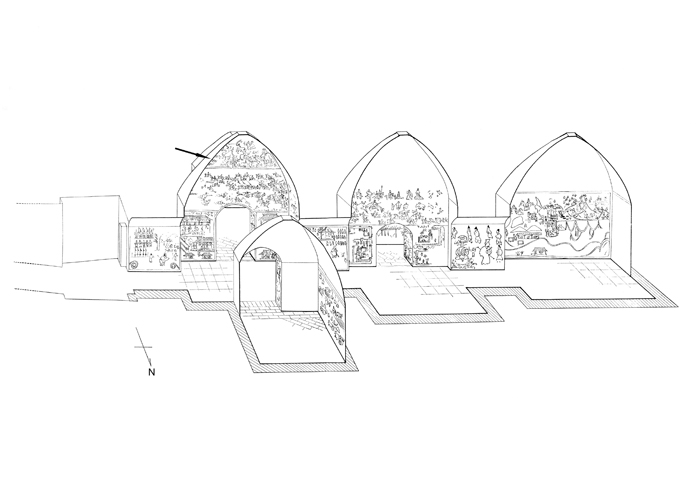

In this paper, however, I will challenge the Buddhist labeling of a particular motif in an Eastern Han tomb and refute the series of Buddhist-related discussions that labeling has engendered thus far. I will examine the so-called Buddhist relics in the famous multi-chambered mural tomb of Xiaobanshen小板申 M1, Xindianzi 新店子 at Horinger [Helinge’er 和林格爾] in Hohhot [Huhehaote 呼和浩特] (Inner Mongolia) (figs. 1, 2).[4] As I shall demonstrate, reading these relics as Buddhist occurred due to methodological infelicities and circular reasoning, shaped largely by deterministic assumptions propagated by the religion’s popularity today and prevailing academic favoritism. More important, a fresh look will help us to discern an important methodological problem in the earlier discourses regarding the introduction of Buddhism to Eastern Han China, particularly since unreliable art historical information often compounds the biases of subsequent scholarship. Once this critical issue is clarified, we can come to a better understanding not only about the tomb at Horinger but also, by extension, the art of death in Eastern Han China.

Part 1

The most enduring controversy over the allegedly Buddhist elements at the Horinger tomb concerns an infamous but now-vanished inscription on the eastern ceiling wall of the antechamber (fig. 2)[5]:

Shēlì猞猁.

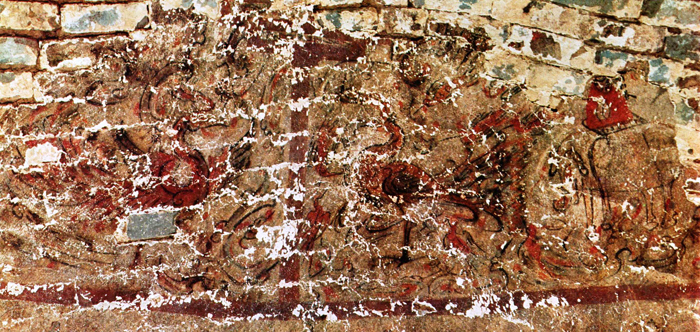

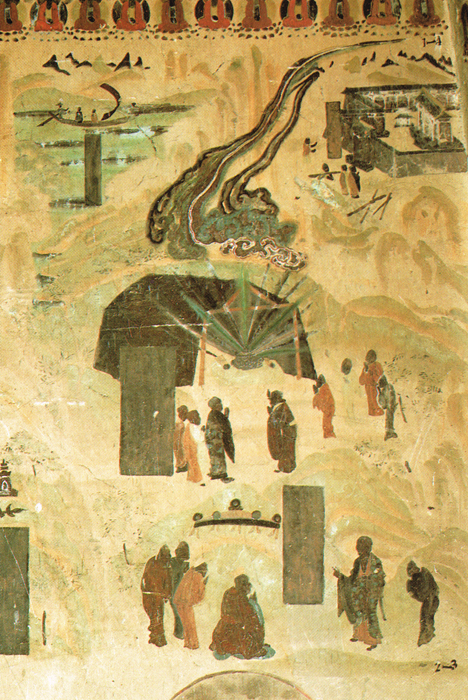

In the corresponding position at the same height in the adjacent southern ceiling is another controversial label, featuring the “white elephant” (baixiang 白象) (fig. 3).[6] Setting aside the Buddhist claim to this elephant for the time being (see below), what is of primary concern for the present moment is Yu Weichao’s proposition that the shēlì 猞猁 inscription on the eastern ceiling was a phonetic exchange for the standard Buddhist shèlì [EMC ɕiah/’ lih] 舍利.[7] However, I doubt that even the original reading of shēlì 猞猁 is correct.

Unfortunately, the cartouche (bangti 傍題) was so badly preserved that it disintegrated before photographs could be taken.[8] Given this circumstance, it is not surprising that the official excavation report does not mention the inscription.[9] Yu Weichao instead refers to unpublished field notes taken by Li Zuozhi 李作智, then of the Museum of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.[10] Li is said to have recorded the condition of the antechamber ceiling when it was first discovered[11]:

... In the east[ern ceiling of the antechamber], there is a painting over the tomb entrance of a serpentine animal with the cartouche of qinglong 青龍 [Green Dragon]. Over this Green Dragon, there is a painting of a figure in the cloudy mist (yunwu 雲霧) seated cross-legged (pantui 盤腿) with the cartouche reading “Dong Wang Gong 東王公” [King Father of the East]. In the patch a little below to the north of the King Father of the East, there is a painting of a pan 盤-vessel shaped thing, inside of which there remain “four globular items” (yuanqiuxing de dongxi 圓球形的東西). On its upper right, there is the two-character label reading shēlì 猞猁.

Regrettably, none of the items mentioned here survived long enough to be photographed. Therefore, Yu Weichao’s source for this unique Eastern Han inscription, with its allegedly Buddhist content, is little more than hearsay. In fact, if one looks closely at the circumstances surrounding the moment the inscription was documented, one finds further reason for concern. Even Yu Weichao was somewhat cautious about the reliability of Li Zuozhi’s work, stating, “On the second of August, 1973, Comrade Li Zuozhi made an additional record from memory.”[12]

It thus appears that the inscription that led Yu Weichao to wax eloquent about Buddhist relics was based on nothing more than a local archaeologist’s memory.[13] Moreover, the inscription was located fairly high above eye level in a dark tomb chamber (see figs. 1, 2). This casts serious doubt on the reliability of Li’s initial reading, quite apart from the difficulties involved in Yu’s Buddhist gloss.

Furthermore, the Buddha’s “relics” (or sacred post-cremation remains) is only one of many meanings for shèlì 舍利, the graph Yu Weichao assumed was behind the vanished allograph shēlì 猞猁, translating śarīra. As Jonathan A. Silk shows, the early stratum of Buddhist translation in China conveyed the ambivalence inherent in the Indic term.[14] Silk pays particular attention to Lokakṣema’s [Zhi Loujiachen 支婁迦讖] vocabulary in the Daoxing banruo jing 道行般若經 (T224), which states[15]:

佛語釋提桓因: 不用身舍利, 從薩芸若中得佛. 怛薩阿竭為出般若波羅蜜中. 如是, 拘翼. 薩芸若身, 從般若波羅蜜中出. 怛薩阿竭, 阿羅呵, 三耶三佛薩芸若身. 薩芸若身生, 我作佛身. 從薩芸若得作佛身. 從薩芸若生我般泥洹後舍利, 供養如故.

The Buddha spoke to Śakra Devānām Indra: “It is not through the bodily-body,[16] but rather from omniscience (*[17]sarvajñatā), that one becomes a Buddha. The Tathāgata emerges from within the Perfection of Wisdom (Prajñāpāramitā). Just so, Kauśika [viz. Indra], the body of omniscience emerges from within the Perfection of Wisdom. The Tathāgata, Arhat, Samyaksambuddha has an omniscience body. When that omniscience body is born, I create a buddha-body. I am able to create a buddha-body from omniscience. After my parinirvāṇa, my relics will be worshipped.

This plain Prajñā School rhetoric shows that the word shèlì 舍利 in Eastern Han Buddhism carried two meanings: the living physical body (shen-sheli 身舍利) and the post-cremation relics (sheli 舍利). Those who advocate the notion that there are Buddhist relics at Horinger have looked for sheli exclusively in the latter sense of the term, believing that they can identify the “ball-shaped objects on a plate” as relics.[18] But they implicitly suggest the former meaning as they do not explain why one should exclude that broader possibility.

Part 2

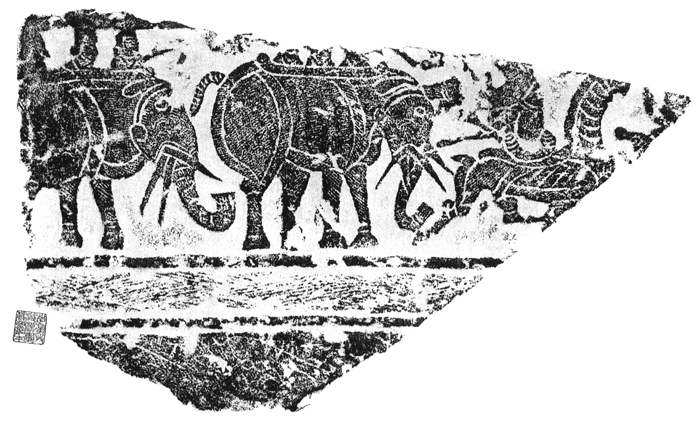

More reliable than this questionable inscription, though, is the tomb itself and its comparison with the totality of second-century Eastern Han (multi-chambered) tombs. Such an archaeological approach very quickly reveals that the Green Dragon and the King Father of the East on the eastern wall were extremely common tomb iconography at the time (fig. 4).[19] Why would the “alien” motif of the shēlì 猞猁—whether or not it stood for the Buddhist shèlì 舍利—irrupt into this otherwise conventional scene? One possible option, which would be compatible with the general nature of Eastern Han tomb iconography and also partially vindicate Li’s reading, would be to assume that the inscription referred to a lynx (shēlì 猞猁) or a similar type of animal that typically populated the exalted landscape of early imperial China.

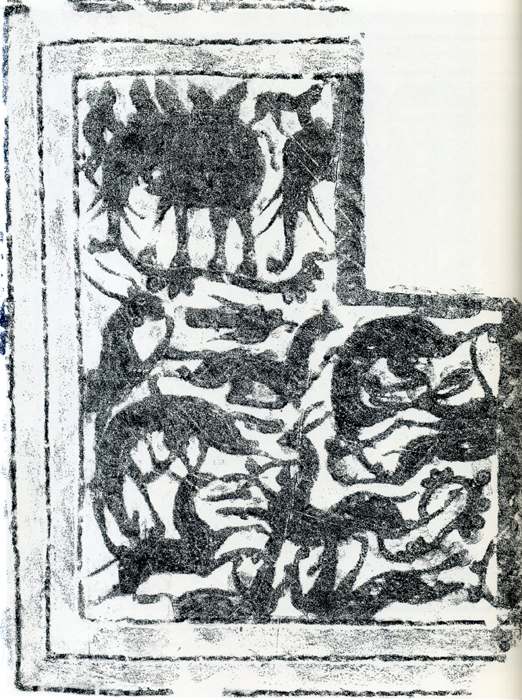

![4. Triangular gable with King Father of the East and the Dragon and other scenes. Rubbing, 158.2 cm (h). Eastern wall of Wu 武 family Stone Chamber 3 (a.k.a. “Wu Liang ci 武梁祠”) at Wuzhaishan 武宅山 in Jiaxiang 嘉祥, Jining 濟寧 (Shandong) Eastern Han period. Princeton University Art Museum (2002.307.34). After Cary Y[ee-Wei] Liu, Michael Nylan, and Anthony Barbieri-Low, Recarving China’s Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the “Wu Family Shrine” (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2005), fig. 1.37 4. Triangular gable with King Father of the East and the Dragon and other scenes. Rubbing, 158.2 cm (h). Eastern wall of Wu 武 family Stone Chamber 3 (a.k.a. “Wu Liang ci 武梁祠”) at Wuzhaishan 武宅山 in Jiaxiang 嘉祥, Jining 濟寧 (Shandong) Eastern Han period. Princeton University Art Museum (2002.307.34). After Cary Y[ee-Wei] Liu, Michael Nylan, and Anthony Barbieri-Low, Recarving China’s Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the “Wu Family Shrine” (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2005), fig. 1.37](/a/ars/images/13441566.0044.008-00000004.jpg)

Considering the deteriorated condition of the murals and the difficult situation that caused for archaeologists, it is possible that Li Zuozhi was looking at an animal but failed to acknowledge it as such. What if the painted thing in question were an auspicious roebuck (zhangzi 麞子), as seen in the contemporary tombs of Suoyaocun 所藥村 M1 at Wangdu 望都, Baoding 保定 (Hebei), or Dahuting 打虎亭 M1 in Mi Xian 密縣 (Henan) (figs. 6, 7)?[20] In this regard, the “four globular items” on a plate could have been a damaged representation (limbs?) of the type of animal that often accompanied the King Father and his consort, the Queen Mother of the West (fig. 5).[21] But even if we concede that Li read the canine (quan 犬/犭) radical in both characters correctly, the phonetic elements constituting the remainder of the two characters might not necessarily have yielded a reading of shēlì 猞猁 lynx. The inscription might have been, for instance, huli 狐狸 fox, an attractive possibility given that the fox, especially its nine-tailed subtype, is frequently a member of the Queen Mother’s entourage (fig. 5).[22] Or what if those globes were meant to represent the elixir of immortality on a plate? Though mere speculation, at least these alternatives do not stray from standard Eastern Han visual grammar for a tomb space.

In fact, a reading of shēlì 猞猁as an auspicious animal is not altogether out of the question. A fantastic beast of a very similar name was known in Eastern Han: the hánlì [EMC ɣǝm/ɣam lih] 含利 monster, mentioned by Zhang Heng 張衡 (78–139) in his Xijing fu 西京賦 (Western Capital rhapsody)[23]:

含利颬颬, 化為仙車, 驪駕四鹿, 芝蓋九葩.

The hánlì, mouth gaping,

changed into a sylph’s chariot,

which was harnessed to a four-deer team

and carried a nine-petal mushroom canopy.

But this is no less untangled a problem, especially because this reading of hánlì in the severely corrupt Xijing fu has the exact variant reading of shèlì 舍利.[24] To make matters worse, the latter reading of shèlì stands against hánlì in Cai Zhi’s 蔡質Hanguan dianzhi yishi xuanyong 漢官典職儀式選用 (Han officials’ administrative ceremonials selected for use), a now-lost but roughly contemporary text to Xijing fu.[25] Of course, we may not be completely assured that Zhang and Cai were both speaking about an identical beast; the graphic similarity between the two words (hánlì 含利 and shèlì 舍利) may be a mere coincidence. But in any case, both Eastern Han authors refer to hánlì/shèlì only to evoke some menagerie of felicities, typical of early imperial iconography, not in a Buddhist context of any kind.[26] Moreover, even if shèlì in both texts is a superior reading of hánlì—although I consider that the opposite is more likely the case, on the principle of lectio difficilior potior, and that shèlì reflects some post-Han, Buddhist-savvy scribal topos—it is still a considerable leap of the imagination to posit a Buddhist-specific etymology for shèlì in Eastern Han belles lettres.[27] In fact, disyllabic words are often transcriptions of foreign words.[28] Accordingly, one might speculate that the animal name(s) used by Zhang and Cai may be of Indic origin and may have taken on a certain zoological character in Eastern Han China different from the original. For instance, there is a bird in Sanskrit vocabulary called śārī/śārika.[29] If so, Yu Weichao was not entirely scrupulous to assert only “the relics” but not allow any possibilities regarding such an exotic bird, the hánlì monster, and so forth. But according to the contemporary parlance of Zhang Heng and Cai Zhi, it seems more logical to view the purported inscription, if it ever existed in the Horinger murals, as a local, epigraphic variant of hánlì rather than a skewed reference to Buddhist relics, as it were.[30] Indeed, I would hypercorrect Li Zuozhi’s field recollection of shēlì 猞猁 to *hánlì 猞猁.

Part 3

One may wonder, moreover, whether Yu Weichao’s emendation of the at least conceivable shēlì 猞猁 (beast) to shèlì 舍利 ([Buddhist] relics) was culturally justifiable in the first place. It is true that the cremated corporeal remains of the Buddha, one of several meanings for the Sanskrit śarīra, often were depicted as globular items in Indian narrative art (fig. 8). As Jonathan Silk’s superb philological study has shown, the Chinese transcription of śarīra as shèlì 舍利 would have been available in theory after Lokakṣema circulated his Buddhist translations, which occurred around the same time as the construction of the Horinger tomb around 180–90 CE.[31] Thus, the issue here is not artistic or philological but sociocultural, and the question is whether the ideological issues involving the Buddhist shèlì 舍利—a term that could variously refer to the body, the corpse, or the cremated remains of the Buddha—would have been known to an Eastern Han audience in the peripheral northern steppe frontier.[32]

For such a sociocultural or anthropological inquiry, the tale of the Giao Chỉ [Jiaozhi] 交趾–born Sogdian immigrant Kang Senghui’s 康僧會 (died 280) first mission to the court of Sun Quan 孫權 (reigned 222–52) at Jianye 建業 is useful, as it throws light on the early sociocultural acceptance of Buddhist relics in China well after the construction of the Horinger tomb.[33] In contrary to Yu Weichao’s unqualified acceptance of the allure of Buddhist relics, the narrative of Kang Senghui’s missionary effort in South China makes it clear that the relics were neither welcomed nor treated with respect, as it is said that the emperor initially felt he’d been “exaggerated to and deceived by” (kuadan誇誕) the missionary (fig. 9). I assume that this nonchalant response typified the sociocultural attitude in early Buddhist China. If this is true, it is exceedingly unlikely that the Horinger muralist was enthusiastic enough about relics to depict them, especially given the tomb’s exceptionally early date and the absence of archaeological parallels. As a matter of fact, no later Chinese tomb murals feature a motif of relics, not even those associated with known Buddhist sympathizers. Buddhist relics probably were very far from the minds of the Horinger tomb painter and his patrons.

Whether or not the term shēlì 猞猁 appears in the inscription at all, it seems highly unlikely that the relics of a deceased person, whether the Buddha or a Buddhist saint, would have been displayed in such a fashion in an Eastern Han context. One has to be sensitive to the psychological effects that relics likely carried in society at that time. Wu Hung asserts, “We could infer that the white elephant and the relics of the Buddha also embody the meaning of xiangrui” [祥瑞] (auspicious omen).[34] But this ignores the possibility that the early Chinese had an aversion toward relics.[35] The idea that the occupant of the Horinger tomb would have put the refuse of a burned corpse (i.e., relics) into an otherwise felicitous landscape populated by auspicious symbols counters everything we know about the psychological underpinnings of Eastern Han iconography. Even if someone at Horinger knew about Buddhist relics, such a person would not necessarily have connected them with xiangrui. After all, the main theme of the murals, at least grosso modo, is the hope for postmortem immortality and comfort.[36] The visual representation of dead bodies or associated by-products is incompatible with such notions, even if the dead body in question belonged to a little-understood and thus powerfully charismatic foreign deity. Arguably, decorating the tomb of one’s ancestors with the ball-shaped remnants of a “barbarian” dead god on a platter would have been conceived as highly unfilial—the breaking of a visual taboo in the Chinese mortuary space, no matter how popular the Buddhist cult of relics may have been.[37] No similar representation of such a macabre theme has been attested anywhere else in Han art (fig. 10).[38] Was the occupant of the Horinger tomb so exceptional in his love of relics? On the contrary, we have literary evidence to demonstrate that an intellectual of a much later date did not consider relics as xiangrui. For example, Han Yu’s 韓愈 (768–824) anti-Buddhist memorial (819 CE) to Emperor Xianzong 憲宗 (reigned 805–20) denouncing the notorious bone relics at Famensi 法門寺 (Dharma Gate Monastery) in Fengxiang 鳳翔, Baoji 寶雞 (Shaanxi) may well be an example of such an aversion.[39] In light of all the problems mentioned above, it seems more probable that Yu Weichao and Wu Hung erred, and there were no relics in Horinger.

In addition to this example at Horinger, murals at other Eastern Han tombs have been associated with Buddhist relics. For example, the ceiling on the middle chamber of Dahuting M2 often is said to feature relics on a plate.[40] But I doubt this, because the claim is based on the suspicious case at Horinger, an example of circular reasoning.[41] Given the research I have outlined above, we should raise questions about the validity of such claims.

Because of this, I want to return to Eastern Han society as a basis for a reconsidering the existence of early Buddhist elements. Eastern Han society was not mired in Buddhist-related mysticism or a Buddhist-hybrid religion. Thus, anyone who argues that a tomb mural has a Buddhist context should explain how the tomb was socially connected to actual Buddhist communities. Any tenuous claims should lose their appeal and should be abandoned for the time being. This is exactly the approach I propose for the Horinger tomb. By reconstructing the way in which modern scholarship became saddled with so-called Buddhist relics at Horinger, I have attempted to show the tenuousness of such claims. Li Zuozhi made the initial mistake and was prudent enough not to publish it. But then the notion that he’d virtually discarded was given wide currency by Yu Weichao in his pursuit of early Buddhist traces in China. We have seen Yu’s speculation that the now-vanished shēlì 猞猁 inscription was actually the Buddhist shèlì 舍利; this was unverified conjecture. There is no verifiable Eastern Han archaeological evidence for this. Regrettably, Yu’s claim now has taken on a life of its own and is widely accepted in Western Buddhological circles.

Erik Zürcher (1928–2008) reintroduced the allegedly Buddhist iconography in the Horinger mural to the West.[42] He mistakenly rendered Yu Weichao’s (or rather Li Zuozhi’s) shēlì 猞猁 as shĕlì 捨俐.[43] This caused a serious problem, for it set a precedent for adducing invalid archaeological data to strengthen the scant historiographic sources for Buddhism in Eastern Han China. When validated by such a famous sinologist as Zürcher, unreliable art historical information compounds the anachronistic biases of other scholars and becomes the basis for all sorts of further speculations.[44] This has affected the study of Eastern Han Buddhism and the Buddhist art of that period, if there even was such a thing. Bad art history drives out good historiography.

Part 4

Having identified the methodological infelicities involved in the reading of shēlì 猞猁, let us turn to another Buddhist controversy in the Horinger tomb. On the southern ceiling mentioned above (in fact, at an equivalent height as the claimed shēlì 猞猁 inscription on the eastern side), there is a mural of a white elephant with an accompanying label (figs. 1 to 3). To demonstrate the elephant’s Buddhist connection, Wu Hung compares it to a well-known depiction of fanciful elephants from Tengzhou 滕州, Zaozhuang 棗莊 (Shandong), calling them “six tusked” and noting that the “six-tusked elephant, which in Indian Buddhism stood for one of the Buddha’s former incarnations, is depicted here driven as an object of tribute, a xiangrui, which represented Heaven’s approval of the Chinese emperor’s rule” (fig. 11).[45] Regarding those transformed elephants of Tengzhou, Wu Hung essentially is embellishing the earlier views of both Lao Gan 勞幹 (1907–2003) and Yu Weichao, but there are problems with these assertions as a whole.[46] First, it is uncertain whether the animal on the rubbing of the Tengzhou stone carvings really had six tusks. I am skeptical; only three tusks are shown, as each elephant is represented in profile. Since Lao Gan’s initial conjecture that there were six, both Yu Weichao and Wu Hung have blithely duplicated that number. In fact, one of the two front tusks of the leading elephant appears to come from behind the trunk. Might there actually be four tusks? There are indeed two four-tusked elephants carved in the contemporary stone reliefs at Longyangdianzhen 龍陽店鎮, also in Tengzhou (fig. 12). Second, even if there were six, and a six-tusked elephant stood for the Buddha’s incarnation in India, one doubts whether such an iconographic concept was available in China, especially as early as the mid-first century CE, the date of the Tengzhou carvings and some one hundred years before any Buddhist text with reference to such elephants likely was translated into Chinese (see below).[47] Third, the fantastic menagerie or procession of auspicious animals—with or without elephants, white-skinned or not—was one of the most widespread features in Eastern Han tombs all across China.[48]

To validate Wu Hung’s statement at least partially, it is possible to emend whether a “white-skinned elephant” (baixiang) rather than a “six tusked” one often was regarded as xiangrui around the mid-first century CE. But Yu Weichao’s assumption—and Wu Hung’s tacit acceptance of it—that the Tengzhou elephants were “white” is unverifiable; we are unable to see any color on the black-ink rubbing (see fig. 11).[49] Fortunately, a group of Eastern Han tombs with stone carvings featuring traces of pigment were excavated at Dabaodang 大保當 in Shenmu 神木, Yulin 榆林 (Shaanxi) in 1996.[50] A door crossbeam from one of the tombs (M24) is decorated with the typical early imperial menagerie motif and an adorable, and yet untransformed, elephant in the center, an architectural context perhaps similar to that of the Tengzhou carvings (fig. 13). The Dabaodang elephant retains a reddish tint around the head, especially on some parts of the lips, eye, earlobe, and trunk. So was it originally pink in color?[51] Should we describe the Tengzho elephants as being pink-skinned instead?

Also, when reviewing Wu Hung’s classical sources to find an explicit definition of the (six-tusked or albino) elephant as a xiangrui, one finds such references mainly in Shen Yue’s 沈約 (441–513) Furui zhi 符瑞志, appended to the Song shu 宋書.[52] This individual text from the Southern Liang 梁 (502–87) dynasty undoubtedly was exposed to the Buddhist environment, so Wu Hung’s use of it might be anachronistic. As a consequence, it is hard to disprove that Shen Yue’s ideas about auspicious elephants were connected to Buddhism due to centuries of cultural conflation. And this does not explain the Eastern Han representations.[53]

Moreover, Wu Hung’s abrupt morphological rendering of the Horinger inscription (shēlì 猞猁) as shèlì 舍利—to strengthen his argument for the Buddhist identification of the elephant in the same tomb chamber—presents its own difficulties.[54] As we have seen, even the transcription (via Yu Weichao) of shēlì 猞猁 by Li Zuozhi has problems; that it is freely interchangeable with shèlì 舍利is even more dubious. Now the Buddhist connection to Horinger’s white elephant is likely as tenuous as that of the claimed inscription of the relics.

Finally, another point needs to be addressed about the actual religious identity of the Eastern Han (white or six-tusked) elephant. I have elsewhere demonstrated that white elephants were not yet Buddhist symbols in the first century CE, and that such things as “Buddhist elephants” in Eastern Han murals are improbable, thanks to preestablished early imperial traditions and the socially marginalized Buddhist position in China (fig. 12).[55] Nevertheless, there is one further nuance to this idea, involving once again the fantastic animals in Zhang Heng’s Xijing fu[56]:

怪獸陸梁, 大雀踆踆, 白象行孕, 垂鼻轔囷.

Strange beasts wildly capered about, and the great bird proudly strutted in.

A white elephant marched along nursing its calf, its trunk dropping and undulating.

The main problem here concerns the semantic vagueness of yun 孕, which David R. Knechtges translates as “to nurse.”[57] This translation seems unproblematic.[58] For example, Xue Zong’s 薛綜 (died 243) commentary paraphrases[59]:

大白象, 從東來, 當觀前, 行且乳.

The great white elephant came from the East.

When it reached the front of the belvedere,[60]

it marched while nursing [its calf].

The fact that Xue Zong lived only a century after Zhang Heng does not guarantee that this commentator from the Eastern Wu 吳 (229–80) was historically exact. Nevertheless, he might have caught his predecessor’s implication in a manner that we might easily miss today. In this respect, it is remarkable that the use of yun 孕 for “nursing” mirrors Xu Shen’s 許慎 (circa 55–149) curious dictionary entry on the elephant (xiang 象) graph.[61] As I pointed out elsewhere, his major concern was with elephantine zoology, especially with the rebreeding interval of three years (sannian yi ru 三年一乳), and he permitted the semantic range of ru 乳 to overlap with chan 產, which was also shareable with yun 孕.[62] This theme of the great nursing elephant continued to be current in the time of the compilation of the Song shu by Shen Yue, who stated[63]:

巨象行乳.

The great elephant marched along, nursing [its calf].

Even in the sixth century, this nursing elephant did not appear in a concrete Buddhist environment but within the familiar landscape of auspicious omens. These occurrences of the same elephantine theme in the works of Xu Shen, Zhang Heng, Xue Zong, Shen Yue, and others clearly suggests that the “nurturing (or reproducing) elephant” was a common trope of long standing that went back to the second century or even earlier (fig. 14). We must remember that the elephantine habitat that Xu Shen alluded to was the exotic locale of Nan Yue 南越. The birth of an infant elephant on Han Chinese soil likely was regarded as extremely auspicious.

Interestingly, Wu Hung’s translation for Zhang Heng’s line is “the white elephant brings about conception” (baixiang xing yun 白象行孕).[64] This transitive use of xing/hang 行 seems unacceptable.[65] Moreover, even if we agreed with the rendering of yun as “conception,” it still would be absurd to assume that the elephant could bring it about. Wu Hung implies that Zhang is alluding to Queen Māyā’s conception of the Buddha. At this point, the problem is no longer merely linguistic, but part of the mutually supporting tangle of arguments concerning “Buddhist” iconography—arguments that I have shown lack a solid basis. Wu Hung states[66]:

This idea was not a part of traditional Chinese thought.... [T]he idea that [Zhang Heng] expresses about “the white elephant bringing about conception” must have originated in Buddhist legends.

As I have just demonstrated, the motif of nurturing elephants was prevalent in Eastern Han literature. Information about the triennial breeding cycle of elephants had circulated in China well before Zhang Heng, and extensive literary and archaeological evidence confirms that elephants were known in China long before Han times (see fig. 14). No hidden Buddhist allusion can be detected between the lines of Zhang Heng’s rhapsody.[67] In fact, the parallel between the great bird and the white elephant as seen in Zhang’s rhapsody is exactly what is attested in the Horinger murals (fig. 3). For this reason, we can rule out Buddhist conjectures concerning the Horinger tomb.

In addition, the textual basis for Wu Hung’s notion that the “Buddhist elephant brings about conception” does not date to Zhang Heng’s lifetime. In fact, Wu refers to Yu Weichao for the narrative of Māyā’s conception through the avatar of the white elephant, and Yu’s locus classicus, the Xiuxing benqi jing修行本起經 (T184), is no longer accepted as an Eastern Han text, although traditionally it has been attributed to Kang Mengxiang 康孟詳 [var. ̊-祥] (active late second century).[68] But even if we wanted to advocate an early third-century date for this Buddhist biography, that date is also too late, postdating Zhang Heng’s rhapsody by a century. In fact, Zhang Heng’s work long predates any extant Buddhist translation into Chinese. It therefore seems ill-advised to insist that there was an established Buddhist tradition by 100 CE that could have exerted any iconography-changing (or paradigm-shifting) influence over a mainstream Chinese writer such as Zhang Heng.

Is it possible that the concept of the Buddhist elephant was transmitted orally during the Eastern Han period and was not documented in any way? Such an idea is pertinent to any art historical study of Buddhist iconography. Indeed, oral transmission was closely related not only to literary tradition but also to visual conventions. We must always consider the possibility that a certain visual iconography was based on oral transmission, or vice versa, without (or before) being passed onto literary texts. But if an intangible oral tradition is the only basis for the theories of Yu Weichao and Wu Hung, why frame them with such “arduous” textual and historical research? Since that research is questionable and only muddies the waters, it might have been preferable to investigate possible early Buddhist and Indian connections in early imperial Chinese art. However, such an argument would fail to convince many scholars. I, for one, question whether Buddhist oral tradition accounts for observable phenomena better explained by the rich, preexisting traditions of auspicious (white-skinned or six-tusked) elephants, which were well-established in literary and artistic realms at least a couple of centuries before the spread of Buddhism in China. Of course, Buddhism existed in India well before the founding of the Chinese empire, and India might have been the ultimate origin of all the elephants depicted in early imperial China. Nevertheless, when the first Buddhist translators began to circulate their initial works for a Chinese audience, these putative Indian elephants already would have been naturalized—after four centuries or so—as thoroughly Chinese auspicious imagery. Moreover, our current state of scholarship does not facilitate the search for archaeological evidence for the transmission of Indian elephant motifs in pre-Qin 秦 (before 221 BCE) China.

Thus I believe the Eastern Han elephants were ramifications of a demonstratively earlier tradition that was not particularly propelled by the social intrusion of Buddhism into China. Not a single scholar has convincingly proved that those elephants had a Buddhist origin. Despite this discouraging conclusion about the social status of Eastern Han Buddhism, however, the preceding analysis conveys one invaluable lesson about the study of early Chinese art: the co-relationship between auspicious symbols and their colorful or directional orientation. For instance, Wu Hung claims that “white elephants as a xiangrui from the West was already a popular concept among the Chinese of the second century B.C.”[69] But this claim, however valid it is in its own context, must be balanced against Xue Zong’s conceptualization that the “great white elephant came from the East” (da bai xiang cong dong lai 大白象從東來).[70] That is to say, whether they came from the West or the East, elephants must have been regarded as auspicious in second-century China. More generally, the color-direction coordinate (what I call the chromato-directional correlation) of a symbol does not necessarily indicate its historical origin.

Conclusion

To conclude, the Eastern Han murals at Horinger do not provide any grounds for a Buddhist reading. The inscription likely was misread by a local archaeologist working in a darkened tomb, and in any case, nothing justifies its identification with the Buddhist term śarīra. Unfortunately, such art historical misidentifications have distorted our picture of early Chinese Buddhism. Now, however, there is an opportunity for a fresh scrutiny of early Buddhist art in China.

Notes

Yu Weichao, “Dong Han fojiao tuxiang kao” 東漢佛敎圖像考 (Notes on the Eastern Han Dynasty Images of Buddha), Wenwu 文物 288 (1980.5), 68–77. For Yu Weichao as one of most accomplished practitioners of modern archaeology in China, see Lothar von Falkenhausen, “Yu Weichao (1933–2003),” Artibus Asiae 64, no. 2 (2004), 295–312.

See Wu Hung, “Buddhist Elements in Early Chinese Art (2nd and 3rd Centuries A.D.),” Artibus Asiae 47, nos. 3–4 (1986), 263–352; Marylin M. Rhie, Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, vol. 1: Later Han, Three Kingdoms and Western Chin in China and Bactria to Shan-shan in Central Asia (Leiden: Brill, 1999); Stanley K. Abe, Ordinary Images (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2002), 10–101.

See Nei Menggu Zizhiqu Bowuguan Wenwu Gongzuodui 內蒙古自治區博物館文物工作隊, Helinge’er Hanmu bihua和林格爾漢墓壁畵 (Murals of the Eastern Han tomb at Horinger) (Beijing: Wenwu, 1978); Gai Shanlin 蓋山林, Helinge’er Hanmu bihua (Hohhot: Nei Menggu Renmin, 1978); Chen Yongzhi 陳永志 and Kuroda Akira 黒田彰 eds., Helin’geer Hanmu bihua Xiaozi zhuan tu jilu 和林格爾漢墓壁畫孝子傳圖輯錄 (Compilation of the filial sons’ cycle in the murals of the Han tomb at Horinger) (Beijing: Wenwu, 2009).

Yu Weichao, “Dong Han,” 68–72. Chen Yongzhi et al., Helin’geer, 80, 169.

The latter graph is, however, not unambiguously xiang 象, though such a reading seems plausible given that the graph occurs next to the painting of the white elephant itself. For example, Gai Shanlin (Helinge’er, 7, 74, 82–83) offered yang 養 instead, while conceding that it might still stand for “elephant.” On purely graphical grounds, something similar to chun 春or quan 券 is also feasible. According to Yu Weichao (“Dong Han,” 69), the preliminary reading of the excavation team was indeed quan. Nei Menggu Zizhiqu Bowuguan, Helinge’er, 34, introduced yet another epigraphic possibility to this elephant glyph, which looks like the quan but with its dao 刀 component replaced with gen 艮, thus similar to juan飬or Gai’s yang. See Minku Kim, “The Genesis of Image Worship: Epigraphic Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China” (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of California, Los Angeles, 2011), 156–71.

Yu Weichao, “Dong Han,” 68–72. The abbreviation EMC stands for Early Middle Chinese, the system of reconstructed sound proposed by Edwin G. Pulleyblank, Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin (Vancouver: Univ. of British Columbia Press, 1991), 278, 188–90. Unfortunately, neither shē 猞 nor lì 猁 was given in Xu Shen’s Shuowen jiezi 說文解字. See Wang Li 王力 et al., eds., Wang Li gu Hanyu zidian 王力古漢語字典 (Wang Li’s Lexicon of ancient Chinese) (Beijing: Zhonghua, 2000), 694–95, 697. Neither form appears in Bernhard Karlgren, Grammata Serica Recensa (Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, 1972), 327; W. South Coblin, A Handbook of Eastern Han Sound Glosses (Hong Kong: Chinese Univ. Press, 1983), 277, 282; Axel Schuessler, Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese: A Companion to Grammata Serica Recensa (Honolulu: Univ. of Hawai‘i Press, 2009), 394, 404; or Tilmann Vetter, A Lexicographical Study of An Shigao’s and His Circle’s Chinese Translations of Buddhist Texts (Tokyo: International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies [ICPBS], 2012), 261–62. It is hence beyond my competency to give any tentative reconstruction of their Eastern Han or EMC sound values here. Rather than let this crucial point slip through, I made an inquiry to W. South Coblin, who shared his expertise and supported my argument, saying, “The compound, as an animal name, is otherwise known only from exceedingly late texts and does not appear to have any identifiable existence in antiquity. And since it does not occur in any Qieyun [切韻] System [QYS] lexica, there is in fact no viable way to assign it a reading within that system, regardless of whose QYS transcription one uses. Additionally, the fact that the original inscription has been lost, if in fact it ever really existed at all, would in any case require us to discount the entire Buddhological argument as overly conjectural.”

Nei Menggu Bowuguan, Helinge’er. Yu Weichao, “Dong Han,” 77 n. 4, also noted that there were inconsistencies between this report and the “in-situ account” (zai muzhong suozuo biji 在墓中所作筆記) drafted in the summer of 1973. Although Yu does not clarify individual discrepancies, the most outstanding difference seems to center on the alleged existence of this shēlì 猞猁 cartouche.

According to Yu Weichao (“Dong Han,” 68–69), this manuscript was titled “Helin Handai bihuamu chuci diaochaji 和林漢代壁畫墓初次調查記” (Preliminary field notes on the Han mural tomb at Horin[ger]), which to date has not been published.

Yu Weichao, “Dong Han,” 68: “Genju jiyi suo zuo bucong jilu 根據記憶所作補充記錄.” Italics are mine.

See Jonathan A. Silk, Body Language: Indic śarīra and Chinese shèlì in the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra and Saddharmapuṇḍarīka (Tokyo: ICPBS, 2006), 11 et passim.

T8, no. 224 (II), 432: a15–20. See Karashima Seishi辛島静志, A Critical Edition of Lokakṣema’s Translation of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (Tokyo: International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology [IRIAB], 2011), 67–68. Translation is Silk, Body Language, 40 with a few of my own emendations, which are intended to maintain Silk’s sense.

This shen-sheli 身舍利 finds parallelism in Zhi Qian’s支謙Da mingdu jing 大明度經. T8, no. 225 (II) 484: a17 (“不用是身舍利得佛也”). This is no surprise: we now consider this to be a revision (retranslation) of Lokakṣema’s archaic Daoxing banruo jing rather than a new version of his own translation of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā. See Jan Nattier, A Guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations: Texts from the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms Periods (Tokyo: IRIAB, 2008), 73–89, 116–48. Silk, Body Language, 38–39, offers an appositional compound of ātmabhava-śarīra for Sanskrit correspondence to shen-sheli.

Here and below, an asterisk indicates a hypothetical reconstruction following the convention of Buddhist philology.

The “ball-shaped objects on a plate” is from Wu Hung, “Buddhist Elements,” 268; Wu Hung, The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art (Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 1989), 139, which was taken from Li Zuozhi’s “globular items” (yuanqiuxing de dongxi 圓球形的東西) in a “pan-vessel shaped thing” (panzhuangwu 盤狀物). See Yu Weichao, “Dong Han,” 69.

For the general program of the Horinger murals, see Anneliese Gutkind Bulling, “The Eastern Han Tomb at Ho-lin-ko-êrh (Holingol),” Archives of Asian Art 31 (1977/78), 79–103; Jiang Wei [江蔚], “Images of Historical Figures in the Helingeer Tomb,” an unpublished conference paper read at the 2013 annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies in San Diego.

For these tombs, see Hsin-mei Agnes Hsu [Xu Xinmei 徐心眉], “Pictorial Eulogies in Three Eastern Han Tombs at Wangdu and Anping” (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Pennsylvania, 2004), 85; Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, “Two Eastern Han Sites: Dahuting and Houshiguo,” in China’s Early Empires: A Re-appraisal, ed. Michael Nylan and Michael Loewe (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010), 83–113, esp. 92. For the iconography of deer as door guardians, see Hayashi Minao 林巳奈夫, “Monban to mon wo mamoru kami 門番と門を守る神,” in Ishi ni kizamareta sekai: Gazōseki ga kataru kodai Chūgoku no seikatsu to shisō 石に刻まれた世界: 画像石が語る古代中国の生活と思想 (Tōkyō: Tōhō Shoten, 1992), 36–49.

For the cult of the Queen Mother of the West, see inter alia Suzanne Cahill, Transcendence and Divine Passion: The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China (Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 1993).

Translation by David R. Knechtges, Wen xuan or Selections of Refined Literature, vol. 1: Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1982), 233. Diacritics are mine. For the discussion of the hánlì 含利monster, see Derk Bodde, Festivals in Classical China: New Year and Other Annual Observances During the Han Dynasty, 206 B.C.–A.D. 220 (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1975), 151–63. Also see Erik Zürcher, “Han Buddhism and the Western Region,” in Thought and Law in Qin and Han China: Studies Dedicated to Anthony Hulsewé on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed. W. L. Idema and Erik Zürcher (Leiden: Brill, 1990), 160–61 (rpt. in Buddhism in China: Collected Papers of Erik Zürcher, ed. Jonathan Silk [Leiden: Brill, 2013], 355–56).

Beside the variant readings of hánlì 含利 vs. shèlì 舍利, this passage (LL. 719–2) involves another serious corruption, that is, hua 化 (change) vs. bei 北 (north), the situation that reaffirms the level of difficulty in dealing with text criticism. Moreover, adding more problems than solutions to the matter, Knechtges, Wen xuan, vol. 1 (1982), 232, promotes the idea of Fujita Toyohachi 藤田豊八, “Zen Kan ni okeru seinan kaijō kōtsū no kiroku” 前漢に於ける西南海上交通の記録 (Records on the traffic between the West and South Seas during the former Han), Geibun 芸文 5, nos. 10–11 (1914), 301–25, 405–14 [rpt. in Tōzai kōshōshi no kenkyū: Nankai hen東西交涉史の研究: 南海篇 (Tōkyō: Oka Shoin 岡書院, 1933), 95–135, esp. 123–24], who suggested long ago that this variant of shèlì 舍利 was “another form” of a gloss to indicate the regions of Shénlí [EMC dʑim liǝ̆/li] 諶離 by the Irrawaddy River, later known as Xīlì 悉利. Fujita’s argument may have certain validity on the etymology of hánlì/shèlì, but does not help our purpose because of the unexplained outstanding phonetic and graphic gaps between shèlì 舍利and shénlí 諶離.

Although Cai Zhi’s text in its entirety has been lost, its reference to shèlì/hánlì is, for instance, quoted in a commentary to Fan Ye’s范曄 (398–445) Hou Han shu後漢書 10, ji 紀 5 (q.v. Xiaoan Di孝安帝), 205: “The beast of shèlì comes from the western direction” (舍利之獸從西方來). Bodde, Festivals, 152ff. is determined to alternate this reading of shèlì 舍利 consistently with hánlì含利 even when he cites Sun Xingyan’s 孫星衍 (1753–1781) reconstructed collection of the Hanguan dianzhi yishi xuanyong, where the variant reading of hánlì含利is not prima facie recognized.

For such themes, see inter alia Leslie V. Wallace, “Chasing the Beyond: Depictions of Hunting in Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Reliefs (25–220 CE) from Shaanxi and Shanxi” (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Pittsburgh, 2010).

In contrast, Bodde, Festivals, 155, views that hánlì含利 “has a more Chinese ring to it” and is the “Sinification” of shèlì 舍利.

See E. G. Pulleyblank, “Chinese and Indo-Europeans,” The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, nos. 1–2 (1966), 9–39, esp. 34; “Zou 鄒 and Lu 魯 and the Sinification of Shandong,” in Chinese Language, Thought, and Culture: Nivison and His Critics, ed. Philip J. Ivanhoe (Chicago: Open Court, 1996), 39–57, esp. 43.

William Edward Soothill and Lewis Hodous, A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms with Sanskrit and English Equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali Index (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1937), 278–9, q.v. 舍利. Bodde, Festivals, 154–55.

See Ruan Rongchun阮榮春, “Dong Han fojiao tuxiang zhiyi: Yu Weichao xiansheng shangque” 東漢佛教圖像質疑: 與俞偉超先生商榷 (Questioning Notes on the Eastern Han Dynasty Images of Buddha: Discussion with Yu Weichao), Dongnan wenhua 東南文化 3 (1986.2), 205–12, esp. 206–7.

For meanings of shèlì 舍利 in translated Chinese Buddhism, see above, n. 16. See Karashima Seishi, A Glossary of Lokakṣema’s Translation of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (Tokyo: IRIAB, 2010), 413–14.

The account is found in Sengyou’s 僧祐 (445–518) Chu sanzang ji ji 出三藏記集. T55, no. 2145 (XIII) 96: b7 et seq. An account that closely parallels this is found in Huijiao’s 慧皎 Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳. T50, no. 2059 (I), 325: b6 et seq. The latter version was fully translated in Édouard Chavannes, “Seng-Houei,” T’oung pao, 2nd ser., vol. 10 (1909), 199–212. For Kang Senghui’s Sogdian network, see Étienne de la Vaissière, Histoire des marchands sogdiens (Paris: Institut des hautes études chinoise, 2002), 77–80 (trans. by James Ward, Sogdian Traders: A History [Leiden: Brill, 2005], 71–74).

Wu Hung, “Buddhist Elements,” 271. For xiangrui, see inter alia Hans Bielenstein, “An Interpretation of the Portents in the Ts’ien-Han-Shu,” Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities [BMFEA] 22 (1950), 127–43; Bielenstein and Nathan Sivin, “Further Comments on the Use of Statistics in the Study of Han Dynasty Portents,” The Journal of the American Oriental Society 97 (1977), 185–87; Bielenstein, “Han Portents and Prognostications,” BMFEA 56 (1984), 97–112; Martin Kern, “Religious Anxiety and Political Interest in Western Han Omen Interpretation: The Case of the Han Wudi Period (141–87 B.C.),” Chūgoku shigaku 中国史學 10 (2000), 1–31. These omens are largely canonized in the “Furui 符瑞” section (zhi 志) of Shen Yue’s 沈約 (441–512) Song shu 宋書. For an overview of the latter, see Tiziana Lippiello, “Shen Yue and his Treatise in Songshu,” in Auspicious Omens and Miracles in Ancient China (Sankt Augustin: Institut Monumenta Serica, 2001), 113–54.

For the concepts of tombs in early China, see inter alia Lai Guolong, “The Baoshan Tomb: Religious Transitions in Art, Ritual, and Text during the Warring States (475–221 BCE)” (Ph.D. diss., UCLA, 2002); Lothar von Falkenhausen, Chinese Society in the Age of Confucius (1000–250 BC): The Archaeological Evidence (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, Univ. of California, 2006), 312–16; Alain Thote, “Les pratiques funéraires Shang et Zhou: Interprétation des vestiges matérials,” in Religion et société en Chine ancienne et médiévale, ed. John Lagerwey (Paris: Institut Ricci, 2008), 47–76 (trans. by Margaret McIntoshi, “Shang and Zhou Funeral Practices: Interpretation of Material Vestiges,” in Early Chinese Religion, pt. 1: Shang through Han [1250 BC–220 AD], ed. John Lagerwey and Marc Kalinowski [Leiden: Brill, 2009], 103–42).

See Gregory Schopen, “Burial Ad Sanctos and the Physical Presence of the Buddha in Early Indian Buddhism: A Study in the Archaeology of Religions,” Religion 17 (1987), 193–225 (rpt. in Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India [Honolulu: Univ. of Hawai‘i Press, 1997], 114–47).

An interesting exception may be, however, the lower portion of the Mawangdui馬王堆 M1 banner, where the shrouded body or coffin of Lady Dai 代on a catafalque seems to be viewed from below. See Michael Loewe, “The Painting from Tomb No. 1, Ma-wang-tui,” in Ways to Paradise: The Chinese Quest for Immortality (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1979), 17–59, esp. 45–46; Sofukawa Hiroshi曽布川寬, Konronzan e no shōsen: Kodai Chūgokujin ga egaita shigo no sekai 崑崙山への昇仙 : 古代中国人が描いた死後の世界 (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1981); Anne Birrell, “Return to the Cosmic Eternal: The Representation of a Soul’s Journey to Paradise in a Chinese Funerary Painting, c. 168 BC,” Cosmos: The Yearbook of the Traditional Cosmology Society 13, no. 1 (1997), 3–30; Huang Bingyi [黃冰逸], “From Chu to Western Han: Re-reading Mawangdui” (Ph.D. diss., Yale Univ., 2005), 248–62.

“Lun fogu biao 論佛骨表,” Changli Xiansheng wenji 昌黎先生文集 39, in Zhonghua zaizao shanben 中華再造善本, ser. 4, vol. 33 (Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chubanshe, 2002), 14, 2v–4v. For translations, see inter alia Edwin O. Reischauer, Ennin’s Travels in T’ang China (New York: Ronald Press, 1955), 221–24.

Wen Yucheng 溫玉成, “Gong yuan yi zhi san shiji Zhongguo de xianfo moshi 公元1至3世紀中國的仙佛模式” (The Dao-Buddhist motifs in first- to third-century China), Dunhuang yanjiu 敦煌研究 (1999.1), 159–70 (rpt. in Zhongguo fojiao yu kaogu 中國佛敎與考古 [Chinese Buddhism and Archaeology] [Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua], 73–94).

See Zürcher, “Han Buddhism,” 164, also cited unchecked by Silk, Body Language, (2006), 53, n. 143. The same error was repeated by Max Deeg, “Why Is the Buddha Riding on an Elephant? The Bodhisattva’s Conception and the Change of Motive” in The Birth of the Buddha: Proceedings of the Seminar Held in Lumbini, Nepal, October 2004, ed. Christoph Cueppers, Max Deeg, and Hubert Durt (Lumbini, Nepal: Lumbim International Research Institute, 2010), 114, n. 83.

For his magisterial contribution to the field, see J. A. Silk, “In Memoriam, Erik Zürcher,” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 31, nos. 1–2 (2008), 3–22.

Lao Kan [Gan 勞幹], “Six-tusked elephants on a Han bas-relief,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 17, nos. 3–4 (1954), 366–69; Yu Weichao, “Dong Han,” 74.

Lao Gan dates the Tengzhou carving to the reign of Zhang Di 章帝 (75–88 CE); Wu Hung accepts this. The legendary Sishi’er zhang jing四十二章經 may or may not date to that time, but that is beside the point, because this purportedly early text lacks any reference to elephants. See Henri Maspero, “Le songe et l’ambassade de l’empereur Ming,” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 10 (1910), 95–130; Tokiwa Daijō 常盤大定, “Kan Mei kyūhōsetsu no kenkyū 漢明求法説の研究” (Study on the story of Han Ming Di’s Buddhist mission), Tōyō gakuhō 東洋学報10 (1920), 25–41; Liang Qichao 梁啓超, “Fojiao zhi chu shuru 佛教之初輸入,” Gaizhao 改造3, no. 12 (1921), 69–79 [rpt. in Foxue yanjiu shiba pian 佛學硏究十八篇 (Shanghai: Zhonghua, 1936), 1–23, esp. 5–7]; Robert H. Sharf, “The Scripture in Forty-two Sections,” in Religions of China in Practice, ed. Donald S. Lopez, Jr. (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1996), 360–71.

For chimerization, hybridity, and other relevant issues relating to animal deformation, see Helen E. Fernald, “Two Colossal Stone Chimeras from a Chinese Tomb,” The Museum Journal 18, no. 2 (1927), 159–73; Alfred Salmony, Antler and Tongue: An Essay on Ancient Chinese Symbolism and Its Implications (Ascona: Artibus Asiae, 1954); Michael Loewe, “Man and Beast: The Hybrid in Early Chinese Art and Literature,” Numen 25, no. 2 (1978), 97–117 [rpt. in Divination, Mythology and Monarchy in Han China (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1994), 38–54]; Barry Till, “Some Observations on Stone Winged Chimeras at Ancient Chinese Tomb Sites,” Artibus Asiae 42, no. 4 (1980), 261–81; Roel Sterckx, The Animal and the Daemon in Early China (Albany: SUNY Press, 2002).

Shaanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo 陝西省考古研究所 and Yulin Shi Wenwu Guanli Weiyuanhui 榆林市文物管理委員會, “Shaanxi Shenmu Dabaodang di 11 hao, di 23 hao Han huaxiangshimu fajue jianbao 陕西神木大保當第 11 號, 第 23 號漢畫像石墓發掘簡報,” Wenwu (1997.9), 26–35; Shaanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo ed., Shaanxi Shenmu Dabaodang Han caihui huaxiangshi 陜西神木大保當漢彩繪畫像石 (Chongqing 重慶: Chongqing Chubanshe, 2000); Shaanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Yulin Shi Wenwu Guanli Weiyuanhui Bangongshi 榆林市文物管理委員會辦室 eds., Shenmu Dabaodang: Handai chengzhi yu muzang kaogu baogao 神木大保當: 漢代城址與墓葬考古報告 (Beijing: Kexue, 2001). For a contemporary tomb nearby with similar iconography and style, see inter alia Shaanxi Sheng Bowuguan 陝西省博物館 and Shaanxi Sheng Wenguanhui Xiezuo Xiaozu 陝西省文管會寫作小組, “Mizhi Dong Han huaxiangshimu fajue jianbao 米脂東漢畫象石 墓發掘簡報,” Wenwu 190 (1972.3), 69–74.

A few local scholars have stated that the elephant is white-skinned, for the rest of its body seems to have a whitish hue. See Wang Weilin 王煒林, “Shaanxi Shenmu Dabaodang Han caihui huaxiangshi,” Shoucangjia 收藏家 (1998.4), 6–8, esp. 6; Qiu Nan 邱楠, Liang Zhaohua 梁昭華, and Wang Yifeng 王軼峰, “Shaanbei Shenmu Daobaodang Han huaxiangshi xingzhi chutan 陕北神木大保當漢畫像石形質初探,” Sichou zhi lu 絲綢之路 165 (2009.20), 17–21, esp. 19. But this white tone is spread all throughout the lintel, including the rugged background. I therefore suspect that the slab was whitewashed for priming, and that most of the actual coloring, applied on top of the whitewash, has not been preserved. Other carvings from Dabaodang in general seem to have had the white primer applied to them. It is probably too conjectural to argue about the elephant’s iconography based on the occurrence of this white primer. Coincidental as it may be, elephants in pink, reddish brown, terracotta color, etc., often feature in several South and Southeast Asian traditions, whether Buddhist or not. See inter alia S. K. Gupta, Elephant in Indian Art and Mythology (New Delhi: Abhinav, 1983), 54; Rita Ringis, Elephants of Thailand in Myth, Art, and Reality (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996), 105, 116, et passim. Nonetheless, it would be far-fetched to claim Dabaodang’s elephant to be connected to such Indian-derived iconography.

Zürcher, “Han Buddhism,” 164–65, however, accepts the Tengzhou elephants as “Buddhist” elements.

Wu Hung, “Buddhist Elements,” 268, 307; Wu Hung, Wu Liang, 139, 397, q.v. she-li 舍利.

See Minku Kim, “Return of the Elephants: Problems of Mistaken Buddhist Identities for the Art of Early Imperial China” (2011), unpublished paper presented as part of Stanford University’s Silk Road Lecture Series, organized by Albert E. Dien. Also see Kim, “The Genesis of Image Worship,” 135–71.

Erwin von Zach (1935), translated this yun 孕 to suckle (säugen) in Die chinesische Anthologie: Übersetzungen aus dem Wen-Hsüan von Erwin von Zach, 1872–1942, vol. 1, ed. Ilse Martin Fang (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1958), 15.

For example, Wang Li, 213, q.v., gives a single definition of huaitai 懷胎: to be pregnant. On the other hand, Bodde (Festivals in Classical China, 160, n. 83) suggests ying 盈 (EMC jiajŋ) in place of yun 孕 (EMC jiŋh) and translates: “A white elephant moves grandly” (italics are mine). See Pulleyblank, Lexicon, 375, 390. Nevertheless, this alternative seems superfluous in this context.

For this particular belvedere, Xue Zong might have alluded to the famous elephant-viewing point of Guanxiangguan 觀象觀 in Emperor Wu Di’s 武帝 (reigned 141–87 BCE) Shanglinyuan 上林苑. See Sanfu huangtu三輔黃圖4; Song Minqiu 宋敏求, Chang’an zhi 長安志 4, 7.

“象; 長鼻牙, 南越大獸, 三年一乳” (The elephant; with a long nose and tusks; is a large animal from/of Nan Yue; bearing single young once every three years [translation is mine]), Shuowen jiezi, 9B: 45r (6102). Kim, “The Genesis of Image Worship,” 137ff.

Song shu 19, Zhi 志 9, Yue 樂 1, 546 (“魏晉訖江左, 猶有夏育扛鼎, 巨象行乳, 神龜抃舞, 背負靈岳, 桂樹白雪, 畫地成川之樂焉”). An almost-verbatim parallel is found in Fang Xuanling’s 房玄齡 (579–648) Jin shu 晉書 23, Zhi 13, Yue xia 下, 718 (“魏晉訖江左, 猶有夏育扛鼎, 巨象行乳, 神龜抃舞, 背負靈嶽, 桂樹白雪, 畫地成川之樂”), cited by Zürcher, “Han Buddhism,” 161, n. 12. Zürcher mistakenly renders this twice-attested juxiang 巨象 as baixiang 白象, taking it as evidence that confirms Yu Weichao’s Buddhist reading of the iconography at Horinger.

Zürcher, “Han Buddhism,” 160, favors Wu Hung’s translation, which he slightly modifies to “the white elephant effecting pregnancy,” over Knechtges’ translation, which I consider superior.

As a matter of fact, Zhang Heng’s Xijing fu might be not completely devoid of Buddhist rapport or Indic terminology. For instance, many scholars agree that its reference to sangmen 桑門 would be an early transliteration of śramana. See E. Zürcher, The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China, 3rd rev. ed. (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 29; Knechtges, Wen xuan, vol. 1, 236; E. Pulleyblank, “Stages in the transcription of Indian Words in Chinese from Han to Tang,” Veröffentlichungen der Societas Uralo-Altaica 16 (1989), 78. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the other images in Zhang’s rhapsody should be interpreted as Buddhist elements.

Wu Hung, “Buddhist Elements,” 271. See Nattier, A Guide, 108. Recently, Deeg, “Why is the Buddha,” esp. 108, 114, has investigated the Chinese inclusion of the bodhisattva as the rider of the elephant in connection with linguistic issues, subscribing to the so-called Gāndhāri hypothesis of early Chinese Buddhist translations. But Deeg’s dating of the Xiuxing benqi jing to the Eastern Han may be anachronistic, and this has led to a circular argument regarding the “Buddhist” iconography of the Horinger tomb.

Wu Hung, “Buddhist Elements,” 272. But Wu Hung’s basis for this impression, i.e., Emperor Wu Di’s xiang zai yu, bai ji xi 象載瑜, 白集西 was likely not about the white elephant at all but rather about an elephant carriage or howdah (xiangzai象載). See Kim, “The Genesis of Image Worship,” 135ff.

Ars Orientalis Volume 44

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0044.008

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.