- Volume 44 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 593kb

Abstract

Many people are afraid of death, both their own and that of others. This is especially true of sudden deaths, which in Japan are said to create threatening ghosts, such as the spirit that formed after the premature demise of Sugawara no Michizane, the celebrated ninth-century scholar and statesman. Michizane’s ghost took revenge on his adversaries, who had unjustly accused him of treason, and unleashed calamities on the then-capital city of Kyoto. To placate this wrathful spirit, the court posthumously absolved Michizane of all charges, reinstated him to his office, raised his rank, deified him as a kami (deity) with the title of Tenjin, and enshrined him at the Kitano Shrine in Kyoto. This paper examines an early-thirteenth century work, the illustrated Kitano Tenjin engi emaki, known as the Jōkyū version, which depicts Michizane as a wrathful spirit but does not explain how he came to be deified as Tenjin or how the Tenjin shrine was founded. Instead, it ends with an illustration of the rokudō or the six realms of existence. The rokudō creed is a pedagogical Buddhist concept that focuses on the living rather than goryō (angry spirits of aristocrats) or cults of the dead. Based on a discovery that Jien, the eminent Tendai priest who probably produced the scroll, had a vested interest in rokudō liturgy, this article focuses on the six realms as an emerging pictorial genre around the time of the Jōkyū Disturbance (1221).

Introduction

The name Kitano Tenjin (Heavenly deity of Kitano) signifies both a location and a person—the shrine Kitano Tenmangū in Kyoto and the deified nobleman Sugawara no Michizane (845–903). Michizane was the first and only historical person to be consecrated as the celestial deity Tenjin and is the main icon at the Kitano Shrine and numerous Tenjin shrines in Japan. His deification in 987 exemplifies the animistic practice of venerating “resentful spirits” (onryō) of the dead during the Heian period (794–1185).[1] Vindictive spirits of aristocrats, termed goryō, were particularly feared due to their propensity to seek revenge on the living through disruptive forces, particularly if the noble died unjustly or as the result of political ill treatment.[2] Michizane, a celebrated scholar and politician who died in exile, was one of the most intimidating goryō in tenth-century Kyoto.

Various biographical accounts about Michizane, including numerous legends and rumors about his vengeful spirit, appeared immediately after his death. Gathering all these stories into a coherent narrative, Kitano Tenjin engi (Origin story [engi] of Kitano Tenjin Shrine) came out at the beginning of Kamakura period (1185–1333). This literary work represents a concerted effort to centralize the cult of Tenjin worship during the early medieval period. The story relates Michizane’s life as follows. Originally a low-ranked scholar-official at court, he rose to the highest offices, becoming minister of the right (udaijin). His promotion provoked the antipathy of powerful courtiers, most notably the minister of the left, Fujiwara no Tokihira (871–909). In 901, Emperor Daigo (reigned 897–930) charged Michizane with treason and exiled him to Dazaifu (in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture), where he died two years later. Soon, strange things started to happen in Kyoto. Most remarkably, within six years, Tokihira himself fell ill and died. This soon was followed by the premature deaths of his male descendants, and his family line came to an end. Convinced that Michizane’s wrath was behind these events, the emperor gave the scholar-statesman a posthumous pardon. But that did not stop tragedy from afflicting his rivals. In 930, lightning set fire to the Seiryōden imperial palace, killing courtiers who had been politically associated with Tokihira. The human toll and structural damages were so great, people feared that Michizane’s vengeful spirit had taken on the identity of the destructive Thunder God (Karai Tenjin). As depicted in the imperial palace scene in the illustrated Kitano Tenjing engi handscroll (fig. 1), the Thunder God created mayhem at court. In shock, the emperor fell ill and died three months later. The demise of Michizane’s enemies as well as a series of natural calamities that struck Kyoto convinced people that the spirit’s wrath was the cause of these misfortunes. In 947, a small shrine was erected at Kitano (later Kitano Tenmangū) to appease Michizane’s spirit. In 987, eighty-five years after his death, Emperor Ichijō (reigned 986–1011) gave Michizane the title Tenjin (formally Tenman Daijizai Tenjin or Heaven-Filling Great Self-Sufficient Heavenly Deity).

Two text-only editions of Kitano Tenjin engi predate the oldest extant picture-scroll (emakimono) version.[3] To avoid confusion, the three editions are identified by the names of the eras in which they were compiled: the Kenkyū version (1194); the Kenpō version (1213–19); and the illustrated Jōkyū version (1219).[4] The Jōkyū version is the oldest among some sixty extant picture scrolls of Kitano Tenjin engi. Housed in the Kitano Shrine treasury, it is composed of a set of eight painted handscrolls and an additional one that includes several unfinished monochrome underdrawings. The finished scrolls, richly colored on paper, illuminate the powerful story of Michizane (Tenjin) in a historically unprecedented large size: over 52 cm in height, with a length of 842 cm to 1,121 cm per scroll.[5]

The Jōkyū version presents several puzzling problems concerning its uncertain authorship, incomplete production, and seemingly inconsequential conclusion. First, its benefactor is not mentioned in the scroll’s introduction. Second, unlike its textual counterparts, the illustrated version leaves out the key episodes that elaborate on the process of Michizane’s deification. Third, his story ends in the sixth scroll; and, without any explanatory text, the subsequent scrolls change the subject to show didactic imagery related to Buddhist cosmology, the rokudō or the six realms of existence. This latter section features a Buddhist monk named Nichizō, who travels through the six realms during a temporary state of death. A scene in the seventh scroll presents Nichizō, seen on far left of figure 2, bearing witness to the suffering existences of those condemned in the fire of hell, one of the realms. The images in the final two scrolls thus create a puzzling narrative disconnect from the preceding story about Michizane.

Some of the earlier depictions showcase the artist’s talent at expressing intimate feelings that evoke pathos. In particular, a scene at the end of the fourth scroll presents a moving image of a deprived Michizane, who lives in despair in his ramshackle provincial house.[6] Using his sleeve to hide his tears, the disgraced former statesman recalls his glorious past as he gazes at an ornately lacquered hamper. It contains an imperial robe, which had been a spontaneous gift from Emperor Daigo at the previous year’s banquet, a token of the ruler’s appreciation of Michizane’s poetry skills. Chrysanthemum patterns, an imperial symbol, on the hamper suggest the irony in the life of the now-fallen minister. Autumn trees and grass in his unkempt yard forecast the end of his life.

The two-part structure of the Jōkyū version—the Michizane legend from the first to the sixth scroll and the Buddhist six realms in the seventh and eighth scrolls—juxtaposes not only mythical and didactic subject matter but also diverse modes of representation, from documentary to aesthetic. The melancholy “Michizane in Dazaifu” is a narrative that builds drama toward Tenjin worship. The hell of repeated resuscitation, for example, teaches the Buddhist concept of endless transmigration. This combining of the Michizane story with the six realms theme, which is not explained in the scroll, concerns both art history and visual and political culture, which I will examine later. This essay also introduces a recent report by historian Abe Yasurō, who discovered a medieval text for a six realms ritual[7] that, I believe, connects the Jōkyū version to six realms imagery. I believe the inclusion of the realms in the Tenjin story was a case of Buddhist pedagogy (hōben) that implied criticism of contemporary politics.

Skillful Means (Hōben) of Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva

The Jōkyū version is distinguished from the text versions of Kitano Tenjin engi by its extensive visualization of the six realms, which suggests a Buddhist practitioner’s involvement. The unnamed author relies on the pedagogical tool of upaya kaushalya (skillful means) or hōben in Japanese. Hōben refers to the Mahayana Buddhist practice of expedience as a means for ending the suffering of others and bringing them to enlightenment. According to Michael Pye, skillful means was established on the pretext that the Buddha’s teaching was too difficult for unawakened ones and required a compassionate and easily understood approach.[8] Fables, guided meditation, and even lies were considered to be expedient means. I include pictorial storytelling as an adoptive, dynamic, and flexible teaching method as well. Upaya, as John Schroeder points out, combines compassion toward unawakened and suffering beings with the wisdom to guide them toward enlightenment.[9] He defines the link between compassion and wisdom as skillful means in the Mahayana tradition.[10]

The term hōben appears only in the Kenkyū and Kenpō text versions, which introduce an allegorical story of a Tendai ascetic monk in a segment that corresponds to the opening vignette of the seventh scroll in the Jōkyū version. The hero is a historical monk, Nichizō (circa 905–985), originally named Dōken, a master of Shingon mysticism. Through Nichizō’s extraordinary experience of traveling in his temporary afterlife, we learn that Michizane has been deified in the celestial realm of the demigods, while Emperor Daigo suffers in hell. Two literary sources of Nichizō’s story survived prior to the Kenkyū version: one is titled Dōken Shōnin meido ki (Memoir of the priest Dōken in the netherworld) in the Fusō ryakki, and the other one is the Nichizō yume ki (Memoir of Nichizō’s dream) in the temple archive of Uchiyama Eikyū-ji in Nara Prefecture.[11] Neither of these older sources mentions the word hōben, which indicates that the authors of the Kitano Tenjin engi incorporated the term to signify that Nichizō’s story was an expedient means of presenting the Buddhist worldview. The illustrated story of Nichizō in the Jōkyū version thus visually achieves hōben without any accompanying text.

The illustration of the seventh scroll begins with the meditating Nichizō in a circular mountain cave (fig. 3). Across the cascading waterfall, the monk flies into the air with a strange, red-skinned creature toward a group of monstrous oni, ogres who guard the gate of hell. This image is not relevant to the story of Michizane Tenjin and would be meaningless unless the audience was already familiar with Nichizō’s strange thirteen-day state of temporary death.[12] The Kenkyū text narrates:

[Around then] there was a priest named Nichizō, who was originally named Dōken, but who changed his name at the recommendation of Kongō Zaō Daibosatsu [Diamond Zaō Great Bodhisattva].[13] Nichizō had confined himself to a mountain cave, the Shō-no-iwaya, on Kinpusen for ascetic meditation since the sixteenth day of the fourth month of 934; he suddenly passed away (tonmetsu) around noon on the first day of the eighth month. Miraculously, however, he returned to life after thirteen days; during that time Nichizō had been shown to every part of the three worlds (sankai) with the six realms [at the lowest of the three worlds], including the palace of the Tenman Dai Jizai Tenjin [i.e., Michizane Tenjin], various parts in and around the Tushita Heaven, and the hell of Lord Enma, all by means of Kongō Zaō’s [Daibosatsu’s] excellent skillful means (zenkō hōben).[14]

The bodhisattva’s compassionate intervention allows Nichizō to take a thirteen-day tour of the various worlds of existence commented on by numerous Buddhist texts. The allegory describes the skillful-means method employed by Kongō Zaō Daibosatsu, which is a composite name for Zaō Gongen, the tutelary deity of the sacred Kinpusen Mountain where Nichizō practiced asceticism, and the Buddhist bodhisattva, Kongō Satta (Sanskrit: Vajrasattva). According to Dōken Shōnin meido ki, Kongō Zaō Daibosatsu (hereafter Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva) is Shakyamuni Buddha’s manifestation (keshin) in Japan.[15] Neither the Kenkyū nor the Kenpō versions mention this synthesis. This association of a native deity with a bodhisattva represents a case of honji suijaku, an early medieval practice that placed Japan’s indigenous kami within the pantheon of Buddhist cosmology. Michizane scholars connect the honji suijaku phenomenon to the modern Japanese theory shin-butsu shūgō (kami-Buddha amalgamation).[16] This is a complex discourse that recently has undergone much scrutiny.[17] Although an examination of honji suijaku is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth noting that the rhetoric reveals both political (the state) and religious (Buddhist) efforts to tame local and secular powers, especially those who supported individual kami. Kitano Tenjin is an example. The 987 deification of Michizane’s wrathful spirit signified the state authority of Emperor Ichijō. Furthermore, in 991, the government officially recognized the Kitano Shrine as one of nineteen preeminent kami shrines. The appearance of Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva in the Kitano Tenjin engi narrative indicates the appropriation of the state-endorsed Tenjin Shrine by Buddhist interests.

Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva performs hōben for the readers (viewers) via Nichizō. His method is to bring Nichizō to all the realms of existences as an eyewitness. This quasi-Buddhist deity is depicted in a form of a monstrous creature, seen on the black cloud in figure 3. He carries Nichizō on his palm and flies into the sky. This scene, however, has long been misread as Michizane’s posthumous identity, named Dajō Itokuten (Chancellor Awesome Deva) of Japan, taking Nichizō into the unseen worlds. Art historian Minamoto Toyomune identifies the monstrous figure as a kishin (demonic deity), and Komatsu Shigemi describes the scene as “Nichizō and kishin, the deity who could be Michizane as Dajō Itokuten, on their way to help the suffering Emperor Daigo in hell.”[18] Komatsu also describes the scene where the same pair appears after crossing the gate of hell as “Nichizō and Michizane as Dajō Itokuten observe hell with sadness” (see fig. 2).[19] The same identification is found in the latest edition of Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (2013), an audiovisual publication with commentary by Nakano Genzō.[20] Confusion between Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva’s image and that of Dajō Itokuten may be due to the visual similarity between the ogre-like figure who carried Nichizō up in the air and the anthropomorphized Thunder God who struck the imperial palace (see fig. 1). Underlying this assumption may be the late Heian rumor that Michizane’s spirit caused the fire in 930 that led to the death of Emperor Daigo; thus the Thunder God–like figure who takes Nichizō must be another manifestation of Michizane. From an iconographic viewpoint, they are identical. Both have glaring eyes; a large, fanged mouth with white spiky beard; horns; and bulging muscles; and wear only a loincloth. But this representation follows the conventionalized illustrations of spirits and demons in folklore. In fact, both images are comparable to those of all the monstrous oni in the hell realm, as depicted in the seventh and eighth scrolls. There is no need to connect the being that takes Nichizō to the Thunder God (Michizane).

In any case, no textual sources support the interpretation that Michizane went to Nichizō or took him to see the realms of hell, and even less that they went to help Emperor Daigo. Rather, it was the bodhisattva who let Nichizō visit Michizane in his grand residence. At this meeting, Nichizō learned that Michizane had the additional title Dajō Itokuten.[21] Moreover, Dajō Itokuten let Nichizō—and thus readers—know that the Thunder God who struck the palace was his number-three acolyte and not the scholar-statesman himself.[22] The episode also reveals that the world of spirits has rankings much like the world of the living. This kind of orderly hierarchy in the spiritual world reveals Buddhist influence in Michizane’s tale. Nichizō’s story is a hōben that presents Buddhism to the world using Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva as a guide.

Nichizō’s allegory would make sense had the Jōkyū version illustrated both his meeting with Michizane (Dajō Itokuten) and Nichizō and Emperor Daigo in hell. The Kenpō and Kenkyū texts describe the pitiable state of the spirits of Emperor Daigo and his ministers as they burn on an iron rod inside the cave of iron, a barred chamber within the hell of repeated resuscitation.[23] Nichizō hears Daigo confess his remorse for his mistreatment of Michizane.[24] Yet these scenes are missing in the Jōkyū version. In fact, even Nichizō and Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva disappear from the illustrations after their first appearance at the gate of hell. Instead, the Jōkyū version ends with a depiction of the six realms.

The Jōkyū version concludes with a Buddhist creed, which suggests the involvement of a Buddhist hand. This may relate to the fact that the Kitano Shrine was administered by the Tendai Buddhist school: the monzeki (priests of the imperial lineage) who headed the Tendai temple Manshu-in also ran the Kitano Shrine office from 947 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. More relevant to this essay, Tendai Buddhism’s power over the Tenjin cult is particularly evident in the allegory later known as the “Pomegranate Tenjin.”[25] This episode, illustrated in the fifth scroll of the Jōkyū version, introduces the eminent Tendai priest Son’i (866–940) who confronts the wrathful spirit of Michizane.[26] As the story goes, Michizane’s ghost warned Son’i not to interfere with his plans of vengeance, but the priest refused to comply. Enraged, Michizane ignited a fire by spitting out the seeds of a pomegranate, but Son’i extinguished it by performing the mystical mudra (ritual hand gesture) of cold water. In short, Tendai Buddhist power was equal to the wrath of the kami Tenjin.

In addition to Son’i and Nichizō, there is a third Tendai monk in the story, whose name is Jōzō (891–964). He is Nichizō’s older brother and a Buddhist practitioner of mysticism. Jōzō performs a secret incantation (kaji kitō) in an attempt to heal the sick Fujiwara Tokihira. The scene at the beginning of the sixth scroll depicts the moment when the courtier Miyoshi Kiyoyuki (also known as Kiyotsura, 847–918), Jōzō’s father, visits Tokihira to see his son’s healing power.[27] Kiyoyuki witnesses the effect of Buddhist incantation, as he sees the irate spirit of Michizane, who appears in the form of two little snakes, coming out of the sick man’s ears. The snakes demand that Kiyoyuki stop his son from continuing the mysticism. As soon as Jōzō stops the ritual, Tokihira passes away. The Buddhist monk held Tokihira’s life, whose esoteric power combatted the vengeful power of Michizane’s onryō. These accounts reveal Tendai Buddhism’s mediation in the ancient practice of onryō worship. Even Michizane’s powerful onryō is put to use in Buddhist lessons about causes and consequences.

Images of the Six Realms in the Jōkyū Version

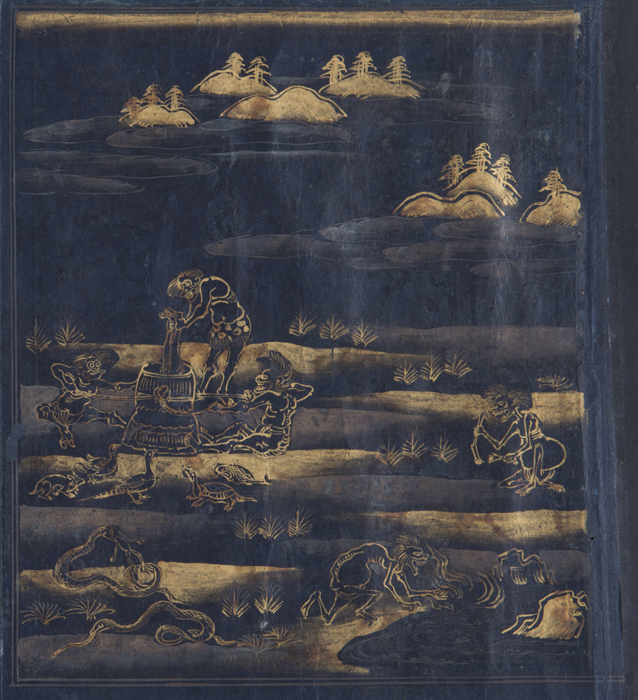

The six realms represent the causally connected states of suffering existence, i.e., the material world. While neither the Kenkyū nor the Kenpō versions describe the realms at all, the Jōkyū version devotes a quarter of its pictorial space to them. Literary sources for the six realms appear in the Tendai monk Genshin’s seminal treatise Ōjōyōshū (Essentials of Salvation, 985).[28] The seventh scroll depicts seven of the eight great hells in vignettes from right to left in accordance with the level of hell. The hell of repeated resuscitation (tōkatsu jigoku) (see fig. 2) continues to the hell of black ropes (kokujō jigoku), crushing hell (shūgō jigoku), screaming hell (kyōkan jigoku), great screaming hell (dai-kyōkan jigoku), hell of burning heat (shōnetsu jigoku), and hell of great burning heat (dai-shōnetsu jigoku).[29] The lowest and the severest level, the ceaseless hell (abi jigoku), at the beginning of the eighth scroll, leads to the remaining five realms: hungry ghosts (gaki), animals, humans, asura (fighting beings), and demigods (lower-ranked celestial beings).

Sin is largely absent in Buddhist tradition. Rather, the Buddhist doctrine of karma dictates that individuals who wronged others are unable to achieve spiritual liberation from the material world.[30] Some offences against Buddhist teachings and community, such as breaking the precepts by eating meat or engaging in sexual acts with ordained monks or nuns, are punishable by damnation in hell. The lower the level of hell, the greater the number of charges. For example, in the hell of burning heat, the sixth level, newly added sinners include adulterers, murderers, thieves, drinkers, and liars who have also slandered the Buddha’s teachings.

The condemned are subject to various forms of torture. The Jōkyū version illustrates horrific oni delivering punishments with spiked clubs, spears, bows and arrows, hammers, and even their massive hands. They beat, stab, and mutilate the guilty. Within the diverse techniques of torture, an ingenious method stands out, as it does not require an oni to operate it, only a self-spinning wheel. Depicted in the scene of the hell of burning heat, a turning wheel with a serrated rim crushes the backbone of a man with a shaven head, a precept-breaking monk. Judging by the method of punishment, the man probably misrepresented and offended the teachings of the Buddha. The wheel makes an apt reference to the Buddha’s law, that is, the Wheel of the Dharma.[31] Here, the spinning image of the wheel has two purposes: it is a vehicle that spreads Buddha’s teaching and a weapon that destroys passions and desires.

The eighth scroll lists all six realms, beginning with the ceaseless hell. Metaphorically, the six realms represent the causal connections between one’s immoral actions and the three poisons or sins of Buddhism: greed (the world of the hungry ghosts), ignorance (the realm of animals), and aversion (the realm of the fighting asuras). The realm of the humans, according to Genshin, is impure, subject to endless suffering (i.e., many rebirths), and transient. The illustration is ingeniously done: after showing the theme of impurity though a view of a charnel pit where carnivorous birds and animals gather around corpses, suffering is depicted in a wealthy household with three rooms that connect the scenes of death, sickness, and birth. These stages of life represent the concept of samsara, the endless suffering of continuous rebirths. The concept of transience is manifested in a scene of a fire that appears at the end of the section depicting the human realm. People in the house—who scramble around saving household items, such as tatami mats, palanquins, a zither, and clothes—represent vanity. They show the futility of their attachment to material things.

The uppermost domain of the six realms is the realm of demigods, which is also a part of the vast expanse of the devas (Japanese: ten), which is subdivided into layers of hierarchical levels.[32] The devas’ realm is theologically complicated, since it spreads over the three worlds of desire, form, and formlessness. Demigods, at the top of the six realms, are the lowest ranked devas. Above this realm, another sphere of heavenly beings within the world of desire makes the base of the two upper celestial worlds of devas. The numerous devas and demigods are classified into specific levels of existence in the cosmology. It is in the realm of demigods that Michizane exists as Dajō Itokuten. In other words, Michizane’s spirit is put into Buddhist cosmology so that it can be subject to the cycle of rebirths. In the Jōkyū version, the image of Michizane as Dajō Itokuten does not even appear. Instead, the final vignette presents beautifully dressed apsara (female spirits) strolling and dancing to music in the heavenly landscape. Yet their blissful existence is limited, and the phase of decay begins. A group of older women with discolored skin, representing aged apsaras, repose in the forlorn landscape. The images relate the fundamental Buddhist teaching that nothing, even in the heavenly realm, is permanent, and thus these heavenly women transmigrate to other realms. The Jōkyū version ends with this bleak imagery.

The Unnamed Author

In the dedicatory preface, the unnamed author articulates the objective of the Jōkyū version:

Many deities protect the capital yet none exceeds the exceptional power (rishō) of the Kitano Shrine deity. Those who worship at the pure and undefiled shrine find their earthly wishes come true.... Thus should the illustrated form of true divinity (honji e-zō) win more hearts to initiate (ketchien) a Buddhist life, Tenman Daijzai Tenjin [i.e., Michizane Tenjin] will be compassionate and grant their wish to connect this world to the next world in [Amida], Buddha’s pure land.[33]

The author produced the scroll to pay respects to the true divinity (honji), an unidentified Buddhist deity who appeared in the form of Kitano Tenjin. The scroll signified his meritorious act on behalf of the shrine. At some point, however, the original goal of venerating the deified Michizane’s powers of protection shifted. Instead of illustrating Michizane’s life, the Jōkyū version elaborates on the Buddhist concept of rokudō. This thematic change has puzzled modern art historians.

In 1956, Shimomise Shizuichi wrote that the imperial rebellion against the Kamakura shogunate in 1221, known as the Jōkyū Disturbance (Jōkyū no ran), had made it impossible to complete the scrolls.[34] After examining the network of politically influential people at the time, art historian Minamoto Toyomune theorized that the aristocrat Kujō Michiie (1193–1252) was the unnamed sponsor and collaborated with his own great-uncle Jien (1155–1225), the eminent four-time Tendai abbot, to produce the work.[35] Minamoto based his theory on observations that the author had to be a member of the Kujō family and a Tendai clergyman, as the Jōkyū version placed Tendai Buddhism and the Kujō branch of the Fujiwara clan in a favorable light. Jien fit the profile. This Tendai monk had a close connection to the Kujō family: his older brother Kanezane and his grandnephew Michiie both served as clan chieftain (fig. 4). Minamoto also noticed the literary resemblance between the preface of the Jōkyū version and Jien’s celebrated text, Gukanshō (1220). Jien wrote Gukanshō as a chronicle of imperial history, beginning with the first emperor (Jinmu). But he also included his personal opinions, such as the importance of the Kitano Shrine as the protective deity for the Kujō family. Another scholar, Nishida Nagao, disagreed with Minamoto, but Kasai Masaaki pointed out that Nishida misunderstood the nuances of Gukanshō.[36]

No new theory arose until art historian Nakano Genzō attempted to identify the person responsible for the strange organization of the Jōkyū version. Nakano argued that the hell scenes in the conclusion were influenced by the year-end services of repentance (butsumyō-e)[37] held at the Heian court. During the service, a set of screens decorated with images of hell stood at the rear of the ceremonial hall, which Nakano compared to the six realms scenes in the Jōkyīu version. He further argued that Saionji Kintsune (1171–1244) produced the Jōkyū version because he wanted retired Emperor Gotoba (reigned 1183–98; died 1239) to repent for scheming against the Kamakura shogunate. Nakano’s analysis has received little, if any, scholarly attention.

The mastermind behind the Jōkyū version must have been a person of intellect with access to a broad range of sources.[38] Who could sort through vast historical, religious, and literary sources to compile such a well-organized hagiography? Who had access not only to the canonical compilations of Nihon shoki, Fusō ryakki, Ōkagami, and Genkō shakusho but also to lesser-known documents from private and provincial sources?[39] Minamoto’s idea that Jien (with the collaboration of Michiie and his family) oversaw the production does seem probable, although there is no consensus among scholars.[40] Jien had connections to high society and religious networks. Yet Minamoto was unable to explain the conclusion of the Jōkyū version; he called the six realms a theme with “little relevance” (sa-made kankei no nai).[41] I believe that Jien’s interest in the six realms became part of the scroll, despite the slight relevance the Buddhist worldview had to Michizane’s life. What follows is a discussion of Jien’s appropriation of Michizane story as an allegory for the retired Emperor Gotoba, with whom the monk had a strained relationship.

Jien and the Six Realms

Jien’s primary source for the six realms cosmology must have been Genshin’s Ōjōyōshū (Essentials of Salvation). It is an encyclopedic text. As Caroline Hirasawa writes, Genshin “stitched together ... scraps of sutras” to create a “drama advocating salvation through faith in rebirth in the Pure Land.”[42] Robert Rhodes reports, “The number of passages quoted in the Ōjōyōshū is enormous ... nearly a thousand borrowed from over one hundred and six different texts.”[43] The idea of dividing existence into six (sometimes five) realms came from India. Several Buddhist scriptures from India—such as the Mahaprajnaparamita Sastra (Commentary on the Prajnaparamita sutra, Daichidoron), volume 30, attributed to Nagarjuna (second century),[44] and the Saddharma smrti-upasthana (The Sutra of the Remembrance of the True Law; Japanese: Shōbenshokyō)[45]—contain lengthy examinations of the realms.

There is little doubt about the historical and religious significance of Genshin and his work. As Rhodes describes, “The Ōjōyōshū, written by Genshin in 985, is perhaps the single most important text in the development of [Pure Land] Buddhism in Japan.”[46] However, Sara Horton argues that while Ōjōyōshū played a limited role when it first appeared, Genshin himself was more important because he organized religious fellowships.[47] I leave the discussion of Ōjōyōshū’s influence in the Heian period to other scholars; my interest is in the role that Genshin played in the Nijūgo zanmai-e (Samādhi Society of Twenty-five), a religious fellowship of twenty-five monks from the Shuryōgon-in, a Tendai sub-temple at the Yokawa retreat on Mount Hiei. The fellowship was established in 986, and Genshin took an active part. It met monthly, chanted Amida Buddha’s name (nenbutsu), and gathered at the deathbed of the dying members. Horton explains that the ultimate goal of this religious group was rebirth in the Pure Land.[48]A liturgical text (kōshiki) was prepared for ceremonies (kō), and Genshin is said to have been the author of the text associated with Nijūgo zanmai shiki,[49] a lengthy ritual. It began with a reading by leaders that described the suffering states of beings, which was followed by the members chanting nenbutsu and verses of praise for each of the six realms.[50] The early Kamakura period saw the spreading popularity of kō societies, which were devoted to specific deities, bodhisattvas, or saints (kami), or specific scriptures, poems, or poets.[51]

In 1999, historian Abe Yasurō published his findings regarding a Buddhist liturgical document in the collection of En’yūzō of Sanzen-in, Kyoto: the primary source, titled Rokudō shaku, is a 1380 copy of Jien’s 1222 original.[52] Rokudō shaku is a variant name of Rokudō kōshiki, the popular name for Nijūgo zanmai shiki during the Kamakura period.[53] In this liturgy, Jien hinted that the deplorable condition that followed the war was a result of deficient governing. The work was intended to admonish retired Emperor Gotoba, the prime instigator of the Jōkyū Disturbance.[54] Abe points out that Jien’s Rokudō shaku departs from Genshin’s Nijūgo zanmai shiki. Instead of treating the condition of suffering in each realm autonomously, as Genshin did, Jien saw the six realms as existing within the human world.[55] It is fascinating that while Genshin conceived of each realm diachronically, Jien explained the human condition synchronically, with everyday life containing elements of the various realms.

The text is organized in four sections that include a short introduction, a six-part liturgical text about the six realms, from hell to heaven, with chanting and praise after each part, and a long reflection as closing remarks. In the conclusion, Jien stated:

Hell represents ceaseless suffering [caused by torture]; hence it is the most deplorable [realm of existence].... Yet don’t acts such as boiling people in a cauldron or pulling out their tongues and hanging them out [to dry] reflect the actions of people?... The asura realm is not explained in detail in the scriptures, and even the Ōjōyōshū omits details.... Who, whether in the capital or in the countryside, courtier or commoner, high or low, has not experienced the same suffering as the asura? Who would not realize that fighting has its rewards? Let me refrain from going into excessive detail, so let us focus on the issue at hand. Victory reflects the power of Three Treasures (sanbō). Defeat is the result of misrule.[56]

Abe comments that Jien’s “reserved” speech easily reveals the target of the criticism—Gotoba—and the loss of his trusting relationship with the emperor was one that Jien felt most deeply in his life.[57] The Rokudō shaku is a liturgical reprimand of Gotoba’s unwise decisions, which took the country to civil war. Jien’s advice to the reader was to “become a member of the monks’ fellowship, and atone all crimes related to three aspects of karma [sangō].”[58] Buddhist sangō refers to sinful actions (such as theft), evil speech (such as lies), and pernicious thought (such as desire). For whom but Gotoba was this advice meant? Although the fact that Jien wrote the Rokudō shaku does not prove that he produced the Jōkyū version, it reveals his knowledge of and interest in these ideas around 1200.

Political Cultures Surrounding the Jōkyū Version

The political climate in Japan around 1200 was complex. As mentioned above, Emperor Gotoba’s pursuit of administrative control, which culminated in the Jōkyū Disturbance of 1221, inspired the production of Jien’s Gukanshō (1220) and Rokudō shaku (1222). Gotoba had little governing power during the period when retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa (reigned 1155–58; died 1192) was still alive, but Gotoba became politically active after his own retirement. His cloistered rule (insei), based in Kyoto from 1198, began to show signs of friction with the shogunate in Kamakura. After the demise of the third shogun Minamoto Sanetomo in 1219, the shogunate appealed to Gotoba to appoint an imperial prince to the shogun post. Gotoba refused to do so, in retaliation for the shogunate’s disrupted negotiations on the issues of taxes and the stewardship of an imperial manor. The shogunate subsequently approached the Kujō family, and Jien’s great-grandnephew Yoritsune (Michiie’s two-year-old son) was chosen as shogun, much to Gotoba’s dismay.[59] In the last chapter of Gukanshō, Jien expressed his hope that the Kujō shogun would unite the military (shogunate) and the aristocracy. He also tried (unsuccessfully) to persuade Gotoba to leave governing to the two authorities and not to rebel.

Jien’s approbation of the Kujō family line was sagacious. He made the Kujō claim to authority a mandate of Tenjin. Gukanshō revealed his personal interest in Michizane, whom Jien called Tenjin. The chronicle entry for Emperor Daigo reads like a tribute to Michizane:

Tenjin is undoubtedly a guise for Kannon Bodhisattva. The incident [accusation of treason] occurred out of his compassion to protect the future of royal decrees. Tokihira indeed committed slander, which brought his own death from Tenjin’s wrath. Had Tenjin regarded all the [Fujiwara] clan as his enemy, the lineage would have been extinct. But the longevity of the regent’s lineage [from Tadahira, Tokihira’s brother] proves that Tenjin considered it best that a small country like Japan should not split the regency into two houses [between Tokihira and Tadahira]. Hence Tenjin willingly accepted [the treason charge against him by Tokihira] to protect the descendants of the regency’s [Kujō-Fujiwara] lineage.[60]

Jien appropriated legends about Kitano Tenjin to augment his narratives about the Kujō family and Tendai Buddhism.[61] In fact, the Kenkyū and Kenpō versions elaborate on the accounts of Fujiwara Morosuke (909–960), the son of Tadahira and founder of the Kujō-Fujiwara lineage. Morosuke expanded the grounds of Kitano Shrine and became the shrine’s custodian in 959. Thereafter, Kitano Tenjin remained the Fujiwara clan’s protective deity.

Jien’s interest in the six realms coincided with his writing of Gukanshō and Rokudō shaku around the time of the Jōkyū Disturbance. This calls attention to the unfinished state of the Jōkyū version. Art historians believe that, like the text-only versions, it originally was meant to complete the consecration story associated with the Kitano Shrine, and they claim the disturbance was the practical reason that forced the project to stop.[62] Their assumption is based on the fact that the Jōkyū version belongs to the engi (origin story) genre, which explains the foundation of a temple or shrine. Since the Jōkyū version lacks a literary title, it is not clear if it were once called the engi of the Kitano Shrine. However, in the postscript of the first scroll, added at a much later time, the then administrative chief of the shrine inscribed:

The sacred engi of Kitano Shrine in eight volumes was inadvertently lost for so many years ... until its discovery in the temple treasury of Ōdera Temple in Sakai City, Osaka, in 1599.[63]

Thus, the Jōkyū version, at least in the late medieval period, was known as an engi scroll, despite the fact it could not fully function as such without Michizane’s consecration story. It includes several unfinished sketches that hint at an initial plan to complete the illustrations in the narrative order of the text-only versions. These fragments, which now make up the ninth scroll, are rough drawings, but they illustrate some critical episodes in the deification of Michizane: Nichizō’s visit with Michizane as Dajō Itokuten; the construction of the Kitano Shrine; the state’s presentation of the Tenjin title; and anecdotes that relate the miracles of Kitano Tenjin.[64] No extant document explains their incomplete status.

The Jōkyū Disturbance likely affected the illustration of Kitano Tenjin engi, but I believe it had a greater impact on the content than on the completion. In other words, ending the scroll with the six realms theme may have been due to the sponsor’s observations of the increasing conflict between the court and the shogunate. Art historical convention dates the Jōkyū version to 1219 based on its dedicatory preface:

[From the time] Emperor Ichijō made the first imperial visit in 1004 until the current day of the first year of the Jōkyū era (1219), nineteen generations of shrine priests have served the Kitano Tenjin. It has been 216 years, but is there a worshipper who has not benefitted from Tenjin’s benevolent protection?[65]

However, the actual production period was long. The Jōkyū version is a large set of scrolls, which involved a great number of hands, including paper artisans, illustrators, calligraphers, and those who mounted everything on the scrolls. According to Suga Miho, it took more than twenty years to finish, which means that the project started around 1200.[66] The production of the Jōkyū version coincides with a time of political turmoil, when the Jōkyū Disturbance was watershed event. The war certainly altered the political landscape, but life and culture in Kyoto had been affected years before the actual rebellion. The latter part of the Jōkyū version probably was produced right before or right after the disturbance, and thus contains reflections on contemporary rather than historical interests.

The six realms theme, which taught about karma, was intended as a particular message to Gotoba and his supporters. Jien had a vested interest in supporting Kujō Yoritsune as shogun. Kujō family members took part in writing the text, as exemplified by the masterful display of the Go-Kyōgoku style of calligraphy, a school established by Kujō Yoshitsune (Yoritsune’s grandfather and Jien’s nephew). It is plausible to consider that a motivation for this organizational shift was to use six realms cosmology to remind Gotoba of the consequences of his misrule. Such a time-dependent circumstance explains why the Jōkyū version was never really copied despite its well-known nickname, the Konpon (Foundational) version. The name highlights the fact that the Jōkyū version is the oldest extant of the sixty-odd Kitano Tenjin engi versions in the world, which together represent the greatest number of illustrated scrolls with the same title.[67] It suggests that the Jōkyū scroll served as a blueprint for later versions that promoted the Tenjin cult. However, according to Suga Miho, the Jōkyū version was neither the oldest nor the prototype: at least three versions (the so-called Sugitani-Shrine version in Mie Prefecture, the Sata-Bunmei version in Osaka, and the Spencer version in the New York Public Library) show traces of painting styles from the late Heian period (mid-twelfth century), although their actual production postdates the Jōkyū version.[68] This means that these three versions had older prototypes than the Jōkyū version. Moreover, none of the other versions imitate the Jōkyū version’s pictorial style or conclusion. Suga’s study reminds us that the art historical practice of organizing artworks according to date of production can obscure different kinds of pictorial lineages and traditions.

Pictures of Hell and the Six Realms

Jien’s interest in the rokudō also sheds light on the Jōkyū version’s curious pictorial organization. The seventh scroll contains only seven of the eight hells, leaving the eighth hell to the next scroll. This arrangement may have been a conscious decision to distinguish two pictorial genres of Buddhist subject matter. Scroll seven represents pictures of hell (jigoku-e) while scroll eight is a stand-alone version of the six realms pictures (rokudō-e), which, of course, include a depiction of hell. Examples of jigoku-e prior to the Jōkyū version are scarce, and images of the complete set of rokudō-e are even more unusual. As such, the Jōkyū version is one of the earliest works to contain images of all six realms, distinct from the generic hell pictures. Few earlier paintings of hell survive, but those that do are not always based on Ōjōyōshū, or they show only a partial section of hell.[69]

The rokudō-e genre has been assumed to fall into same category as jigoku-e. Miya Tsugio has found just one extant Nara period example of a hell scene, on the eighth-century bronze mandorla, a nimbus panel behind the eleven-headed Kannon statue in the Nigatsudō Hall of Tōdaiji, Nara.[70] The scene, though barely visible, consists of flaming mounds with the condemned inside. The executioners who attend the fire do not resemble their medieval counterparts. Miya points out the cartoon-like comical expressions of the condemned in the fire.[71] Fire is the only indication of the fearful hell, and none of the other realms are shown.

The number of pictorial examples increased during the Heian period, and most date to the twelfth century. As Caroline Hirasawa notes, the surviving hell images from the Nara through the Heian periods consist of only a few sketches.[72] Some notable works include the early Heian portrayal of flesh-eating creatures that appear on the right-hand, outermost zone of the famous Womb Mandala at Tō-ji that Kūkai (774–835) took back from China.[73] Their appearance—dark skin, fangs, vicious facial expressions, disheveled hair, and loincloths—suggests that they may have served as prototypes for later images of oni. Perhaps the most famous is from a set of the so-called Chūsonji kin-gin-ji issai-kyō (Complete Lotus Sutra in gold and silver letters at Temple Chūsonji), dedicated by Fujiwara no Kiyohira (early twelfth century), whose frontispieces include images of the three lower realms (fig. 5). Not only are the three realms conceived in one simple landscape, they are interdependent: hungry ghosts and animals feast on human remains from hell.

The term rokudō-e is first mentioned in association with the imperial art collection of retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa. His interest in collecting art motivated Taira no Kiyomori (1118–1181) to consecrate a treasury, the Renge-ō-in (in the current Sanjū-sangen-dō area) for him. A letter by Prince Sonshō (1194–1229), dated 1233, documents that he took some scroll paintings, “including the rokudō-e,” out of the Renge-ō-in on behalf of Emperor Go-Horikawa (reigned 1221–32).[74] No one is certain which works Prince Sonshō removed. Go-Shirakawa used to own the famous illustrated handscrolls Jigoku-zōshi and Gaki zōshi, most of which are now in the Tokyo and Nara National Museums.

Prince Sonshō’s coining of the term rokudō-e indicates an awareness of a new pictorial subject matter. This, in turn, led to the establishment of an academic convention that identified post-Kamakura paintings of hell or hungry ghosts as examples of rokudō-e, whether they appear alone or as a group. Conversely, the category jigoku-e became associated with a pictorial tradition from the previous era, a convention popular in the Heian period. Scholar Sugamura Tōru, in his discussion of the rokudō-e history, treats pre-thirteenth century jigoku-e as part of the rokudō-e genre, and locates the Jōkyū version as a transitional stage between the older and the newer trends.[75] I agree that the Jōkyū version is art historically located at a critical juncture, but I also think it is important to distinguish the two types: the jigoku-e in the seventh scroll, the old-school (Heian period) pictorial genre, and the rokudō-e in the eighth scroll, the new (Kamakura period) six realms imagery. The particular attention paid to depict all of the six realms may reflect the rise of numerous Rokudō kōshiki liturgical texts, abridged versions of Nijūgo zanmai shiki—Jien’s Rokudō shaku being one of them.

Conclusion: Kitano Tenjin Engi as a Buddhist Hōben

The Jōkyū version contains two disparate systems of thought. The legend of Michizane as a wrathful spirit (onryō), depicted in the first through the sixth scrolls, relates to the mid-Heian belief in goryō cults that linked the tragic deaths of aristocrats to spirits that haunted their former homes. Michizane’s story is a lesson about not causing harm to others and the consequences of one’s immoral actions. The seventh and eighth scrolls offer a didactic visualization of the six realms concept. Both the moralizing narrative and the visual representation represent the pedagogical tools of hōben. At the narrative level, Nichizō’s story demonstrates the power of Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva, and the audience shares the monk’s awe-inspiring experience. At the didactic level, the audience learns about the six realms of existence. The Jōkyū version exercises the author’s hōben, similar to Kongō Zaō’s skillful means, to edify the rokudō creed for the audience.

The genius of the producer of the Jōkyū version is the visual articulation of the six realms images (rokudō-e), separate from the general category of the pictures of hell (jigoku-e). While the revenge story resonates animistic belief in the power of goryō, Nichizō’s adventure puts the deified Michizane and the condemned Emperor Daigo in the context of Buddhist cosmology. Although the perpetrators’ suffering is not illustrated in the scroll, the educated audience would have known that was happening; even emperors were not except from the laws of causes and consequences. In other words, the revenge of Michizane Tenjin elucidates the Buddhist law of karma, a larger frame for the six realms concept, which also teaches about impermanence, transience, and the endless cycle of rebirth. According to this law, therefore, even the divine Michizane was not exempt from karma. Nichizō finds Dajō Itokuten (Michizane Tenjin) in his vast palace, described in the text versions as an opulent landscape, similar to Amida Buddha’s Pure Land. Unfortunately the illustration of the palace, though sketched, was never finished. Nevertheless, what the reader must not overlook is that Dajō Itokuten is ensnared in the physical world of the demigods. In other words, his palace is not a Buddhist pure land. He still dwells in the world of rebirth just above the six realms according to the hierarchical structure of three-world cosmology. Neither Dajō Itokuten nor the emperor was exempt from the law of transmigration. In short, the old goryō tradition was folded into Buddhist cosmology, a medieval (thirteenth-century) rationalization of ancient (tenth-century) animism.

This is why the illustrations of the six realms come last. The decomposing bodies of heavenly maidens are a perfect way to end the scroll. Such images belong to a tradition that illustrates the Buddha’s teaching of impermanence. In “Dead Beautiful: Visualizing the Decaying Corpse in Nine Stages as Skillful Means of Buddhism,” I discuss how the Buddha’s original teaching about transience changed when a woman’s body became the object of meditation.[76] Meditating in front of a woman’s decomposing corpse was in part aimed to curb monks’ sexual desires while they witnessed the illusion of corporeality. By medieval times in Japan, depictions of women’s putrefying corpses had become canonized as nine-stage decomposition images (kusō-zu). Genshin’s Ōjōyōshū had much to do with the pictorial canonization of the kusō-zu: Six Realms of Transmigration (Rokudō-e, late thirteenth century) from Shōgū Raigōji, a set of fifteen hanging scrolls, includes one (the human realm) that depicts female decomposition in nine stages.[77] The Jōkyū version presents only five stages, matching the five phenomena of decay that belong to the realm of demigods. According to Genshin, the first sign of putrefaction is the woman’s soiled robe; second, her withering flower crown; then the foul stench on the body; sweat from the armpits; and finally the loss of satisfaction in the realm.[78] These symptoms, rather profane, show earthly concerns. The idea of unhappiness in the heavenly existence begs notice. Heavenly beings who continue to be attached to material culture (clothes and crowns) will not be free from desire and decomposition.

The same message is found in the human realm. While Genshin provides scriptural teachings of impurity, suffering, and impermanence in general terms, the Jōkyū version’s illustrations give a situational setting for each image. What appear to be ordinary, everyday scenes are in fact an immediately comprehensible set of metaphors. As the fire scene shows, nothing is permanent. The material world is fleeting, just as fire consumes things, making them into nothing. Viewers would have easily identified with the theme, which makes the pictures effective teaching tools. As Alicia Matsunaga points out, these realms are not static, separate layers; rather, each realm is dynamic and coexists with the other worlds.[79] What Jien rendered in his Rokudō shaku was that the characteristic aspects of the six realms are not specific to each realm but manifest as various phases of life. After all, these lessons were aimed at human audiences. Perhaps the most important aim of the Jōkyū version, the core of its hōben, may be to draw attention to the danger of material attachment. This is true even of the scroll itself, for it too is an illusion.

Notes

Robert Borgen details the deification process of Michizane in four stages. See Robert Borgen, Sugawara no Michizane and the Early Heian Culture (Cambridge, MA: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University Press, 1986), 307–25.

Allan Grapard, “Religious practices,” The Cambridge History of Japan: Heian Japan, ed. Donald Shively and William McCullough (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 559.

The three versions show slight philological differences, which indicates that the later versions are not the copies of older ones. These versions are based on a number of older sources, including the ninth-century biography, Kanke den (or Kanke goden, “The biography of the Kan [i.e., Sugawara] family,” circa 931–47), written by one of Michizane’s grandsons, possibly Sugawara no Aritsune (dates unknown), within fifty years of Michizane’s death.

The Jōkyū version is also Romanized as the Shōkyū version in art historical writings in English, as in Miyeko Murase’s seminal work, “The Tenjin Engi Scrolls: a study of their genealogical relationship” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1962). Although Shōkyū has become the convention, I will use Jōkyū in this article to reflect the Japanese reading of the era.

Traditionally, the illustrations are attributed to the court painter Fujiwara no Nobuzane (circa 1176–1265). S. C. Bosch Reitz, “Tenjin Engi; A Thirteenth-Century Japanese Painted Scroll of the Kamakura Period,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 21, no. 5 (May 1926), 123.

See, for the illustration, Komatsu Shigemi, Kitano Tenjin engi: Nihon emaki taisei 21 (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1978).

I am indebted to Professor Abe Yasurō for pointing out his exciting discovery to me. Abe Yasurō, “Jien saku ‘Rokudō shaku’ o megurite: Jien ni okeru shūkyō to rekishi oyobi bungaku” (Regarding Jien’s text “Rokudō shaku”: Jien’s religion, history, and literature), Bungaku, Tokushu: Chūsei bukkyō no bunkaken. 8, no. 4 (1997), 28–50.

Michael Pye, Skilful Means: A Concept in Mahayana Buddhism, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2003), 1.

John Schroeder, Skillful Means: The Heart of Buddhist Compassion (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001). Liz Wilson recognizes that skillful means as “salvific stratagems” is a typically Mahayana concept; she also points out how the idea of expedience crosses over the divisions of Mahayana and Theravada schools. Liz Wilson, Charming Cadavers: Horrific Figurations of the Feminine in Indian Buddhist Hagiographic Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 116–22.

Neither of the originals exists. “Nichizō yume ki” is in the Meiji-period compilation, Kitano bunsō, vol. 11. Takei Akio, “Dōken Shōnin meido ki, Nichizō yume ki, bikō” (Thoughts on the Dōken Shōnin meido ki and Nichizō yume ki, supplemental), Jinbungaku, vol. 176 (2004), 1–25.

Takei, “Dōken Shōnin meido ki, Nichizō yume ki, bikō”; and Kasai Masaaki, Tenjin engi no rekishi (History of the Tenjin legends) (Tokyo: Yūzankaku, 1973). For a modern Japanese transcription of the Kenkyū version, Ikesugi Asako’s translation is available online: Ikesugi Asako, Kenpō-bon Tenjin Engi (Nabari-shi, Mie-ken, Japan: Nabari Tenjin engi emaki Kenkyūkai), [formerly http://www.h3.dion.ne.jp/~ya.ike/Kenpōbon.htm]. The Kenpō version of Kitano Tenjin engi lists the date of Nichizō’s temporary death as 934. The Kenkyū version of Kitano Tenjin engi does not specify a date, while the Fuso ryakki does—941.

The name Nichizō derives from a short verse that Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva gives to Dōken, “Nichizō kuku, nengetsu ōgo.” It means “Nichizō lives nine times nine [eighty-one] years under divine protection.” Indeed, Nichizō (formerly Dōken) died at the age of eighty-one. Kasai Masaaki, Tenjin engi no rekishi, 59

Kitano Tenjin engi, Kenkyū version (1194), transcription in Kasai Masaaki, “Kitano Tenjin konpon engi no kisoteki kenkyū” (Preliminary study of the Kitano Tenjin konpon scroll), Jinbunkagaku 74 (1964), 78. The translation is mine.

“Dōken Shōnin meido ki,” the Tenkei 4 (934) entry in Fusō ryakki, compiled in “Nihon itsushi, Fusō ryakki,” in the Kokushi taikei, vol. 6 (Tokyo: Keizai Zasshisha, 1901), 709. The text is digitized at Kindai Dijitaru Raiburarī of National Diet Library online, http://kindai.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/991096.

Mitsuhashi Tadashi, “Kitano Tenjin engi to shinbutsu shūgō shisō” (The Kitano Tenjin engi and the philosophy of kami-buddha amalgamation), in Kitano Tenjin engi o yomu, ed. Takei Akio (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2008), 126–48.

Kuroda Toshio, for example, warns that the term “amalgamation” is misleading because Shinto was not an independent religion until the modern era. As Mark Teeuwen and Fabio Rambelli explain, Kuroda’s thesis, which radically departs from earlier scholarship on Shinto history, combines local kami cults and Buddhism at various levels, including institutional and doctrinal. Mark Teeuwen and Fabio Rambelli, Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm (London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003). See also Kuroda Toshio, Nihon chūsei no kokka to shūkyō (The state and religion in medieval Japan) (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1975); Kuroda Toshio, Ōhō to buppō: Chūseishi no kōzu (Imperial law and Buddhist law) (Kyoto: Hōzōkan, 1983). Allan Grapard, The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

Minamoto Toyomune, “Kitano Tenjin engi emaki ni tsuite” (On Kitano Tenjin engi emaki), in Kitano Tenjin engi, Nihon emakimono zenshū 8 (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1959), 12. Komatsu Shigemi, Kitano Tenjin engi: Nihon emaki taisei 21(Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1978), 31.

Nakano Genzō, commentary, Nazotoki Tenjin-sama no emaki: Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Unraveling the secrets of the Kitano Tenjin engi scrolls), ed. Ueda Masaaki (Tokyo: Dōhōsha Media Plan, 2013). The DVD contains inconsistent identifications. The voiceover narration explains that Nichizō was guided by Kongō Zaō Bodhisattva, while the descriptive chapter titles on the DVD cover read “Scroll 7—Ascetic Nichizō is led by Michizane in the tour of hell,” and “Scroll 8—Nichizō sees Emperor Daigo suffering in the hell of Six Realms in his dream.”

Grapard, “Religious practices,” 561. The name indicates an association with Daiitoku (Sanskrit: Yamantaka), a deity whose mount is the bull, the symbol used during popular rainmaking rites. Michizane’s spirit also was associated with the bull.

Nakano Genzō, Zoku zoku Nihon bukkyō bijutsushi Kenkyū (Kyoto: Shibunkaku Shuppan, 2008), 141.

This scene is not depicted in the Jōkyū version, but the (fourteenth-century?) Chikugo Province version of the Kitano Tenjin enji illustrates Nichizō bowing before Emperor Daigo and ministers.

Minamoto, “Kitano Tenjin engi emaki ni tsuite” (On Kitano Tenjin engi emaki), in Kitano Tenjin engi, Nihon emakimono zenshū 8 (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1959), 6.

See, for the illustration, Komatsu, Kitano Tenjin engi, 24–25. Son’i appears twice in the fifth scroll of the Jōkyū version. The second story repeats Son’i’s mystical ability: he was called to the palace when the Thunder God struck, but the Kamo River, overflowing due to the storm, blocked his way. He then performed another miracle by crossing the floodwaters on an oxcart. Illustrated in Komatsu, Kitano Tenjin engi, 26.

Translations of the names vary from scholars to scholars. I refer to the translation by Haruko Wakabayashi, “Officials of the Afterworld: Ono no Takamura and the Ten Kings of Hell in the Chikurinji engi Illustrated Scrolls,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36, no. 2 (2009), 331. The entire corpus of Genshin’s Ōjōyōshū has not yet been translated into English, but Wakabayashi provides succinct explanations of the eight hells. For the translation of the hell section, see August K. Reischauer, trans., “Genshin’s Ōjō Yōshū: Collected Essays on Birth into Paradise,” Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 7 (1930), 16–97. For this article, I consulted Ōjōyōshū, in Kokuyaku Daizōkyō, ed. by the Kokuyaku Daizōkyō henshūbu (Tokyo: Tōhō Shoin, 1928–22). The text is digitized at Kindai Dijitaru Raiburarī of National Diet Library online, http://kindai.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1172341/168.

A. Bloom, “The Sense of Sin and Guilt and the Last Age [MAPPO] in Chinese and Japanese Buddhism,” Numen 14, no. 2 (1967), 144–49.

The connection between the wheel image and the Buddha’s teaching was discussed in the 2011 Buddhist Art Seminar report by two of my graduate students, Brinker Ferguson and Laura Beavers.

Genshin, Ōjōyōshū, in Kokuyaku Daizōkyō, ed. by the Kokuyaku Daizōkyō henshūbu (Tokyo: Tōhō Shoin, 1928–22), 349-350, digitized at Kindai Dijitaru Raiburarī of National Diet Library online, http://kindai.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1172341/168.

Kitano Tenjin engi, Jōkyū version (circa 1221); see Komatsu Shigemi, ed., “‘Kitano Tenjin engi’ kotobagaki shakubun” (Transcription of the Kitano Tenjin scroll inscription),” in Kitano Tenjin enji, ed. Komatsu Shigemi, Nakano Genzō, and Matsubara Shigeru (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1978), 118. The translation is mine.

Shimomise Shizuichi, Yamatoeshi: emakimonoshi (History of yamatoe, history of emakimono) (Tokyo: Fuzanbō, 1956), 184.

Kasai Masaaki, “Kitano Tenjin konpon engi seiritsu no shūhen (josetsu)” (On the circumstances surrounding the composition of the Kitano Tenjin konpon scroll [introduction]), Jinbungaku 107 (1969), 24–29.

Nakano Genzō, “‘Kitano Tenjin engi’ no tenkai—Jōkyū-bon kara Kōan-bon e” (The development of the Kitano Tenjin engi—from the Jōkyū version to the Kōan version), in Kitano Tenjin enji, ed. Komatsu Shigemi, Nakano Genzō, and Matsubara Shigeru (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1978), 90. For the imperial butsumyō ritual, the hell pictures (rather than the images of the six realms) were used; Nakano notes only one case in which the six realms pictures were used.

Kasai Masaaki, “Kitano Tenjin konpon engi seiritsu no shūhen” (On the circumstances surrounding the composition of the Kitano Tenjin konpon scroll), Dōshisha Daigaku Jinbunkagaku Kenkyūjo Kiyō 7 (1964), 17–43; Suga Miho, “Chūsei ni okeru Kitano Tenjin engi emaki no seisaku” (On productions of medieval Kitano Tenjin engi emaki), in Kitano Tenjin engi o yomu.

Miyeko Murase lists twenty such relatively obscure medieval documents that supplied sources of information for the Kitano Tenjin engi. Miyeko Murase, “The Tenjin Engi Scrolls,” 23–26.

Takei, Kitano Tenjin engi o yomu (Tokyo: Yoshikwa Kōbunkan, 2008), 23.

Minamoto Toyomune, “Kitano Tenjin engi emaki ni tsuite,” 12.

Caroline Hirasawa, “The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination, Monumenta Nipponica 63, no. 1 (2008), 8.

Robert F. Rhodes, “Ōjōyōshū, Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki, and the Construction of Pure Land Discourse in Heian Japan,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 34, no. 2 (2007), 252–53.

Miya Tsugio touches briefly on the rokudō thoughts in India. See Miya Tsugio, Rokudō-e, Nihon no bijutsu [Japanese art], no. 271 (Tokyo: Shibun-dō, 1988), 17.

The scripture is attributed to Gautama Prajñāruci (fourth–fifth centuries). See Daigan Matsunaga and Alicia Matsunaga, The Buddhist Concept of Hell (New York: Philosophical Library, 1972), 75. The original Sanskrit is lost, but the Tibetan and Chinese translations can be found in the Taishō Tripitaka.

Sarah Horton, “The Influence of the Ōjōyōshū in Late Tenth- and Early Eleventh-Century Japan,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 31, no. 1 (2004), 29–31.

Sarah Horton, “Mukaekō: Practice for the Deathbed,” in Death and the Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism, ed. Jacqueline I. Stone and Mariko Namba Walter (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 27.

Yamada Shōzen, “Nijūgo zanmai shiki,” Taishō Daigaku Sōgō Bukkyō Kenkyu-jo Nenpō, vol. 4 (1982). Yamada Shōzen, “Kōshiki to wa nani ka (1, 2, 3): Bukkyōbunka no ensō (What is kōshiki 1, 2, 3: The center of Buddhist culture),” Daihōrin (December 1983), 22–28; (January 1984), 36–44; and (February 1984), 50–57. Niels Guelberg, “Buddhist Ceremonials (kōshiki) of Medieval Japan and Their Impact on Literature,” Taishō Daigaku Sōgō Bukkyō Kenkyūjo Nenpō, vol. 15 (1993), 254.

Abe Yasurō, “Jien saku ‘Rokudō shaku’ o megurite: Jien ni okeru shūkyō to rekishi oyobi bungaku” (Regarding Jien’s text “Rokudō shaku”: Jien’s religion, history, and literature), Bungaku, Tokushu: Chūsei bukkyō no bunkaken 8, no. 4 (1997), 35.

David Quinter, “Invoking the Mother of Awakening: An Investigation of Jōkei’s and Eison’s Monju kōshiki,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 38, no. 2 (2011), 264.

Jien, Rokudō shaku, transcription in Abe Yasurō, “Sanzen-in Enyūzō Rokudō shaku honkoku” (Transcription of Rokudō shaku in the collection of Sanzen-in Enyūzō), Bungaku, Tokushu: Chūsei bukkyō no bunkaken 8, no. 4 (1997), 47, 49. The translation is mine.

Jien, Rokudō shaku, in Abe Yasurō, “Sanzen-in Enyūzō Rokudō shaku honkoku,” 50.

Ishida Ryōichi, Gukanshō no kenkyū: sono seiritsu to shisō (A study of Gukanshō) (Tokyo: Perikansha, 2000), 39.

Jien, Gukanshō, in Kokushi taikei, vol. 14, Hyakurenshō, Gukanshō, Genkō shakusho (Tokyo: Keizai Zasshisha, 1901), 436; http://kindai.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/991096. The translation is mine.

Kasai Masaaki, “Kitano Tenjin konpon engi seiritsu no shūhen (josetsu)” (On the circumstances surrounding the composition of the Kitano Tenjin konpon scroll [introduction]), Jinbungaku 107 (1969), 38–39.

For a full discussion, see Minamoto, “Kitano Tenjin engi emaki ni tsuite,” 12–13; and Nakano, “‘Kitano Tenjin engi’ no tenkai,” 92–94. Minamoto considers it possible that the six realms section was a supplementary part of the (never-finished) complete story of the Kitano Tenjin scroll.

Kitano Tenjin engi, Jōkyū version (circa 1221), transcription in Komatsu, “‘Kitano Tenjin engi’ kotobagaki shakubun,” 120. The translation is mine.

These sketches used to be pasted on some of the finished scrolls as enforcing backing paper. Nakano, “‘Kitano Tenjin engi’ no tenkai,” 96.

Kitano Tenjin engi, Jōkyū version (circa 1221), transcription in Komatsu, “‘Kitano Tenjin engi’ kotobagaki shakubun,” 118. The translation is mine.

Suga Miho, “Chūsei ni okeru Kitano Tenjin engi emaki no seisaku” (On productions of medieval Kitano Tenjin engi emaki), in Kitano Tenjin engi o yomu (Reading the Kitano Tenji engi), ed. Takei Akio (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobun-kan, 2008), 196.

Suga Miho, “Tenjin engi emaki, dejitaru-akaibu ni yoru ruihon no hozon to kiso shiryō no kōchiku” (English title by Suga: Buildup a digital archive along an essential reference database of the Tenjin Engji’s analogs scrolls group), in Kagaku kenkyū-hi hojokin kenkyū seika hōkokusho, Okayama Daigaku (2010), n.p.

Suga Miho, “Chūsei ni okeru Kitano Tenjin engi emaki no seisaku,” 180.

Sugamura Tōru, “Jigoku-e, rokudō-e no rekishi no naka no Kitano Tenjin engi emaki” (Locating the Kitano Tenjin engi scroll in the history of hell pictures and six realms pictures), Kitano Tenjin engi o yomu, ed. Takei Akio (Tokyo: Yoshikwa Kōbunkan, 2008), 153.

Miya Tsugio, Rokudō-e, Nihon no bijutsu [Japanese art], No. 271 (Tokyo: Shibundō, 1988), 18-19.

Caroline Hirasawa, “The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination,” Monumenta Nipponica 63, no. 1 (2008), 6.

These creatures, known as yasha and rasetsu (Sanskrit: yaksas, raksasas), originate in Hindu mythology from the Vedic period. Michelle Osterfeld Li, Ambiguous Bodies: Reading the Grotesque in Japanese Setsuwa Tales (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 123.

Komatsu Shigemi, “Gaki, jigoku, yamai-zōshi to rokudō-e,” Gaki-zōshi, Jigoku-zōshi, Yamai-zōshi, Kusoshi emaki; Nihon emaki Taisai 7 (Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Sha, 1977), 135.

Sugamura Tōru, “Jigoku-e, rokudō-e no rekishi no naka no Kitano Tenjin engi emaki,” 175–76.

Ikumi Kaminishi, “Dead Beautiful: Visualizing the Decaying Corpse in Nine Stages as Skillful Means of Buddhism,” in A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, ed. Rebecca Brown and Deborah Hutton (Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012). See also Fusae Kanda, “Behind the Sensationalism: Images of a Decaying Corpse in Japanese Buddhist Art,” The Art Bulletin 87, no. 1 (2005), 24–49; and Gail Chin, “The Gender of Buddhist Truth: The Female Corpse in a Group of Japanese Paintings,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 25, nos. 3/4 (1998), 277–317.

For the full description and discussion of the Shōgū Raigōji version, see Kokurho: Rokudō-e (National Treasures: Rokudō painting), ed. Kyoto Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan (Kyoto: Kyoto Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, 1982).

Genshin’s explanation is based on his reading of the Parinirvana Sutra. Komatsu, Kitano Tenjin enji, 43.

Alicia Matsunaga, The Buddhist Philosophy of Assimilation (Tokyo: Sophia University; Rutland, VT: C. E. Tuttle Co., 1969), 48.

Ars Orientalis Volume 44

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0044.007

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.