- Volume 44 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 418kb

Abstract

Hero stones commemorated many forms of noble behavior in ancient India, such as death in battle, fights with wild animals, or death while protecting other people or cattle. The memorial stones discussed here were unusual in that they were memorials to individuals who decapitated themselves for religious purposes. Abstract religious principles were not sufficient to create a climate conducive to religious self-decapitation. Changes in politics, sectarian movements, and societal stress factors such as war, religious persecution, epidemic disease, or famine could and did influence an individual to take his or her life. The memorial stones at Mallam, Andhra Pradesh, covered a period of several hundred years and reflected the changes in Hindu religious life in South India from the Pallava period through the Vijayanagara period.

As a man casts off worn-out garments and puts on new ones, so the embodied soul casts off the worn-out body and enters other new ones ... [The soul] is everlasting, all-pervading, stable, firm and eternal.

—Bhagavad Gita, chapter 2, verse 27

This quote from the Gita reflects the integrative and accepting approach that infused the Indian perspective on death. At discrete moments in India’s long history, this attitude allowed individuals to seek death with a light-hearted resolve that seems extraordinary to modern observers.

An unusual collection of stone memorial sculptures is found in the Teliṅgāṇa area in the small village of Mallam in Nellore District in lower Andhra Pradesh (fig. 1). The sculptures are uncommon for a number of reasons, but this article will focus on the remarkable nature of the self-sacrificial acts they commemorate. The nineteen stelae record and honor the self-decapitation of male Hindu devotees in self-sacrificial rites.[1] The visual subject matter is so startling and the underlying ideas so disturbing, it is well worth studying these small plaques.

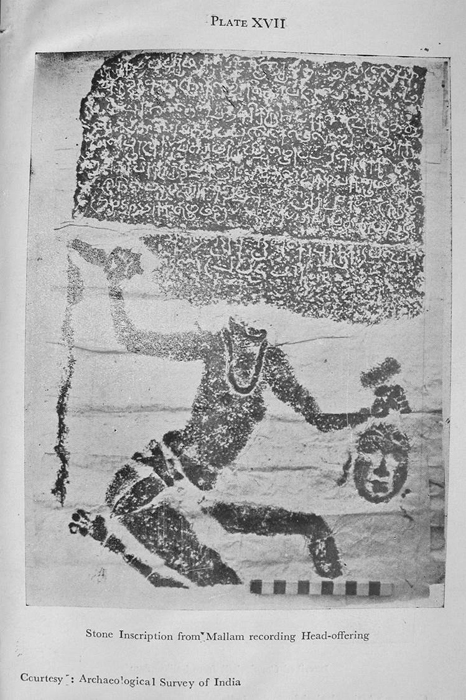

The sculptures currently are arranged around the northern gateway to the circa eleventh-century Subrahmaṇya temple in Mallam village. Subrahmaṇya is an alternate name for Murugan, or Kārttikeya, the Hindu god of warfare and the son of the Lord Śiva. The stone sculptures range in date from the Pallava period (circa second to ninth century) to the Vijayanagara period (1336–1646). Most seem to be from the Cōḷa period (fourth century to 1279). One stela, stylistically among the earliest, is dated 889, during the reign of the Pallava king Kampavarman; this is also the only stone at the Mallam site with an inscription.[2] Since the current temple construction is later than some of the stones, it is likely that this was not the original location for the memorials. While some of the stones originally may have been placed at or near this location, others probably were gathered from surrounding fields and villages and placed around the Mallam temple in the early twentieth century by Archaeological Survey of India workers.[3] Because of the lack of relevant inscriptional material on the temple, it is impossible to determine if the temple itself was the site of the self-sacrificial activities memorialized on the stones.

These stone memorials are visual messages that arose from a range of beliefs about divinity, death, and sacrifice. The images on the stelae present complex ideas in a vocabulary that is simple yet capacious enough to include the mystery of death. Significantly, they represent a paradigm shift in ideas about the presentation of sacrifice, from the impermanent expression of a fluid, repetitive, and aniconic Vedic sacrifice to the permanent, discrete, and iconic world of Purāṇic[4] Hinduism. They also represent a shift in access to divinity; the self-sacrifice of these religious oblates required no brāhman intermediary to be placed between offerer and god. Their message was available to anyone who saw them, literate or illiterate; they did not need to be interpreted by the literate elite.

Sacrifice is the foundation of many religions, because it is based on the assumption that men and gods need and feed each other; it forms the heart of social communion, because it creates reciprocal communication with the divine. Gods become understandable and biddable through sacrifice, and thus life becomes more stable and predictable. Sacrifice structures the relationship between god and mortal, and it also controls the interaction between sanctity and violence. The control of social violence inevitably gives rise to cultures where individuals can see beyond their personal impulses to form societal relationships and direct behavior toward altruism and more empathetic social structures.

It has been argued at various times in India’s long religious history that the most intimate and generous oblation is the free offering of the body through self-chosen death. Why this was so was determined by the exigencies of Indian history: religious practice and social stressors joined to create a climate amenable to self-oblation.

Our understanding of existence is divided between the immediacy of daily life and the enigma of death. Self-chosen death was symbolically poised to balance creation and destruction and act as a transactional bridge between the known and the feared. Self-sacrifice addresses the inevitability of death, as the inexorable but unfathomable counterpart to life. By controlling death through self-destruction, the offerant puts himself in a contractual reciprocity with the divine, the administrator of death. Through self-sacrifice, the offerant demands communication with the gods; this act is both supremely humble in its self-annihilation and defiantly arrogant in its hubris.

We often think of death as something remote that needs to be addressed, however unwillingly, in a far off moment, not needing thought on this particular day. As Marcel Proust remarks in The Guermantes Way:

We may, indeed, say that the hour of death is uncertain, but when we say so we represent that hour to ourselves as situated in a vague and remote expanse of time, it never occurs to us that it can have any connection with the day that has already dawned, or may signify that death—or its first assault and partial possession of us, after which it will never leave hold of us again—may occur this very afternoon, so far from uncertain, this afternoon every hour of which has already been allotted to some occupation.[5]

These stones commemorate offerants who believed that, as the supreme culmination of life force, death held power—not remote, but immediate power—which could be controlled and manipulated through the grace of sacrifice.

The symbolic control of suicide manages the dichotomy of life and death. In Greek mythology, Persephone dies for half the year to ensure fertility for the rest of the year. In Christianity, the image of God/Man in self-chosen creative death offers believers a path to redemption through the oblation of Jesus, the Seal of Sacrifice. In Buddhism, the entirely self-sacrificing bodhisattva is an ideal of spiritual altruism and the major expression of moral behavior within Mahāyāna. In Hinduism, the primordial man Puruṣa and the goddesses Satī and Chinnamastā[6] embody different aspects of transformative and transcendent self-sacrificial death.

Many traditions moved beyond the mythic to explore actualization. Some believers did not just dwell on the symbolic and distanced word; they physically emulated and enacted the myths. Early Christianity, expecting an imminent Day of Judgment, and thus sanctified martyrdom as the highest form of devout expression, one that would hasten the End of Days. Islam inspires some of its believers to accept a martyr’s death in jihad. Jainism glorified self-extinction by the starvation ritual of sallekhanā. Buddhism wrestled with ideals of self-sacrificing bodhisattvas and strictures against self-harm,[7] at times keeping the distance between abstract mythic paradigms and at other times being forced to address religious suicide. At discrete periods Hinduism also condoned and even glorified religious self-destruction as a vehicle for transcendence and liberation.

That religious self-sacrifice actually took place in ancient India, and was not merely metaphoric or symbolic, may be attested by the numerous memorial stones commemorating the heroes who “abandoned the body”[8] in the rite of dehatyāga.[9] A Tamil inscription from one of the earliest Mallam stones unequivocally records that during the twentieth year of the reign of King Kampavarman (889), a hero offered his flesh in a nine-part ceremony that culminated in his head sacrifice to Bhaṭārī, a local tribal goddess whose identity eventually was subsumed into the cult of Durgā.[10] It is inscribed that in honor of this sacrifice the offerer’s family was given a tract of land.[11]

The inscription is chiseled above the shallow relief figure of a genuflecting man holding a sword high in his right hand and his severed head in his outstretched left hand (fig. 2). The face of the severed head is shown with eyes closed and expression solemn, but undistorted by fear or pain. The muscular body is twisted in such a way that the headless torso confronts the viewer, but the lower body is in profile.[12] This technique was no doubt a device to show the importance of the offerer by portraying him as fully as possible. The pose in its unrealistic formality also helps to enforce the feeling of solemnity and the timeless quality of the ritual.

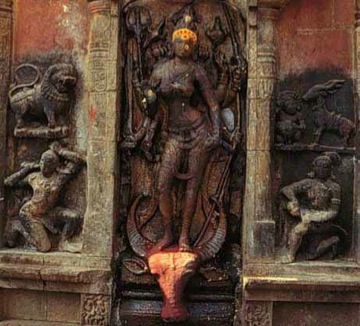

Eventually, during the Kākatīya (1083–1323) and Vijayanagara periods, artists used a variety of poses to portray sacrificial decapitation, but this dual frontal profile/genuflecting pose was the standard for head-offering bhaktas (followers of the charismatic tradition of bhakti devotionalism) during the Pallava and Cōḷa periods. Later sculptures usually show the offerer facing forward, standing as opposed to kneeling, and with the sword held either at the side or back of the neck or, in later images, with the sword held to the base of the throat (fig. 3). While the fully frontal pose is more immediate, personal, and dramatic, it is also less removed, solemn, and hieratic than the earlier depictions.

In the Karnataka area, two tenth-century inscriptions without imagery are also testaments to the practice of head-offerings to the goddess. A 991 CE Karnataka record in Sorab Taluk refers to a man named Katega who vowed to offer his head to the goddess Guṇḍadabbe of Hayve if the king were blessed with a son. When a royal son was indeed born, Katega kept his promise.[13] A 944 CE inscription from the Coorg area of Karnataka records that a man named Buciga cut off his own head.[14] The Tamil Kalingattuparaṇi contains a passage that indicates that by the eleventh century the full valorization of the practice of self-decapitation had been established. Describing a sacrifice ritual at a South Indian Kālī temple, the text states: “Like the roaring sound of ocean waves, the shouts of heroes offering their heads in return for the bestowal of boons were echoing all over the area.”[15]

Numerous South Indian hero stones record the practice in pictorial form but are not inscribed with explanatory material. We now live in a period of almost universal literacy (at least as an ideal), and it seems peculiar to us not to record names, dates, and reasons for such an unusual act. However, this was not the usual situation in ancient India, where literacy was rare and confined to the upper castes, and religious practice was shifting away from Brāhmanic oral control of sacrifice to the personal and charismatic expression of the images of Purāṇic bhakti.[16] The Mallam Pallava period stone is thus significant because it is both an inscriptional and a pictorial record of the sanctioned practice of religious self-oblation. This early stone indicates that abandonment of the body was permissible and was so honored the performers and their families were formally elevated in status and wealth.

Hero stones—known by various regional and linguistic terms such as pāliyā, khambhi, khatri, chara, vīragal, vīrakkal, vīraṣilalu, naṭukal chāyāsthambha, etc.—are not confined to any one geographical area, although they are particularly numerous in South and West India. The memorials may be arranged near temple walls, under trees, by the roadside, at the base of fort ramparts, or grouped about a samādhi or chhatri (funerary or cremation memorial) of a famous individual. Because the artwork is often crude and simple, the stones have often been ignored. However, they are revealing social documents. Because of the recent interest in satī, and the relatively large number of satī stones, this type of memorial is fairly well known. Satī stones, however, memorialize only one particular form of heroic death: that of the devoted wife who chose to accompany her husband on the funeral pyre. Hero stones may commemorate many forms of courageous death: in battle, in cattle raids, in fights with wild animals, while protecting the weak and helpless, and, as in the case at Mallam, during a self-sacrificing religious offering.[17]

The Mallam stones are unusual in that they specifically commemorate the self-sacrifice of men who offered their heads in devotion to Hindu deities. The stones are also significant because they were made over such a broad period of time, thus indicating that in this area, at least, head offerings were an accepted form of religious self-sacrifice for hundreds of years. They represent the visual memorials of common men, not kings or great warriors, but individuals heroically seeking god through self-sacrifice.

Mallam is in the lower southeast corner of Andhra Pradesh; it was at the crossroads of Pallava and Cōḷa, and then later the Kākatīya, Reḍḍi, and Vijayanagara cultural maṇḍalas. All of these societies practiced religious self-immolation, sometimes in honor of Śiva Bhairava, but usually the sacrifice was made to the goddess Durgā in one of her more violent aspects.

No matter how devout, no one chooses religious suicide casually. Self-sacrifice might be supported by interpretations of religious belief, but those interpretations were made in favor of an actual, rather than metaphoric, sacrifice only when other social and biological pressures were present. Self-sacrifice was performed in fulfillment of a vow that might be taken for a variety of expressed religious, military, political, or social-biological, reasons, such as the duress of religious persecution, lack of a royal heir (presaging political instability), war, famine, or epidemic disease. Many of these elements could be simultaneously at play to inspire an individual to take his own life to honor the divine.

It is likely that the impetus for the Mallam self-oblations stemmed from two historical periods, each with its peculiar catalysts. The earlier memorials were produced in a period that Sanskritized and formalized indigenous South Indian tribal traditions to serve the formation of imperial ambitions under the great Pallava, Cōḷa, and Cāḷukya empires. It was also the period of the rise of both bhakti and Tantra[18] in South India, religious systems that encouraged fervent religious expression. Kings were vying for control, and South Indian monarchies fought seemingly endless wars for empire. They needed the support of their goddesses, often violent deities who did not give their favors without exacting a high price.

This period also experienced biological disasters. The world’s first plague pandemic, the Plague of Justinian, raged from 541 to 775.[19] It was followed by outbreaks such as the Plague of Emmaus of 639 and others in the seventh and eighth centuries. Plague became such a devastation in India that by the eleventh century the Bhāgavata Purāṇa was giving instructions for its prevention.[20]

The fourteenth century saw the terrible devastation of the bubonic plague on a world-wide scale. Black Death, named for the black gangrenous pustules it formed in the lymph nodes of the neck, underarms, and groin, is thought to have originated somewhere in the Steppes region. The bubonic plague bacterium (Yersina pestis) is found in fleas that infest black rats, which traveled with the disease across the globe via trade ships and the camps of the Mongol armies. The Black Death is estimated to have killed at least a third, if not half, the world’s population in the fourteenth century.[21] There are numerous reports of this astoundingly lethal disease and the ensuing social breakdown.

Sudden and seemingly uncontrollable epidemics have historically produced radical response. Thucydides wrote about the extreme behavior of the usually rational Athenians in the face of sudden lethal contagion in the epidemic of 427 BCE. Eyewitnesses as diverse as Giovanni Boccaccio and Pope Clement VI reported on the panic and the often specifically religiously hysterical behavior engendered by epidemics in medieval Europe.

These dreadful outbreaks of malignancy probably set the stage for a radical religious response in South India. It is difficult to imagine how most people would react in the face of such suffering, but looking to a divine cause would not be unusual in a deeply religious culture. The desire to bargain with the gods must lead to sacrifice, for what more precious commodity can be offered than oneself? When devastating disease brings about uncontrollable and widespread death, it is natural to think of negotiating with the divine: “save my children, and I will offer my life in the future;” “save my king, and I will offer my life;” or “save my own health for a few years, and I will then offer my life.”

Sacrifice: Its Nature and Functions (1898) by Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss is the seminal work on our modern anthropological understanding of sacrifice. Hubert and Mauss posit that sacrifice is more than a totemic transaction or gift to the gods, it is “a religious act which, through the consecration of a victim, modifies the condition of the moral person who accomplishes it....”[22] In other words, its value lies in the sacral transformational power of the ritual. During self-sacrifice the sacrificer and victim are one and the same, and they are transformed through death into a consecrated being linked to the divine. In this linkage, the sacrificer/victim can communicate and even make demands from a position of sacred equality. Hubert and Mauss emphasize the contractual covenant of sacrifice.

Sanctioned Self-Destruction

Taking one’s life for a religiously sanctioned purpose averted the opprobrium of suicide. Although suicide occasionally may be viewed with sympathy, its disruptive aspects are such that its condoned performance is usually carefully delineated. Indian society condemned suicide, but honored, even glorified, self-sacrifice. The distinction between the two is acute, for the suicide is portrayed as weak and dissolute, while the self-oblate is elevated to the ranks of an apotheosized hero. In contrast to the disturbance of suicide, a community is well served by altruistic self-sacrificial behavior, because it is a social benefit for individuals to repress individual instincts, needs, and desires for the perceived greater good, such as community health or political stability. Communal harmony is threatened by suicide. With self-sacrifice, society may congratulate itself on the nobility of the actor; with suicide, social systems must confront failures.

The general attitude in early Indian literature was to condemn self-destruction, but there was also ambivalence. The semi-legendary lawgiver Manu stated that no absolutions or funeral rites were to be offered to the suicide[23]; but he also stated that a person could expiate a great sin by self-destruction.

The ambivalence to suicide is reflected in the Īśavasya Upaniṣad (verse 3), which denounced the individual who took his own life: “Those who take their lives reach after death the sunless regions, covered by impenetrable darkness.” The Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (10.2.6.7) prohibited suicide, stating: “And therefore one should not die, desirous of heaven, before one’s [allotted] lifespan [is complete].” The Kanthaśruti Upaniṣad, however, allowed that “the sannyāsin [Hindu renunciant], who has acquired full insight, may enter upon the great journey, or choose death by voluntary starvation, by drowning, by fire or by a hero’s fate.”[24] It is evident from these early sources that self-destruction was not only permissible, it could be justified by an enlightened person who took his life with sanctioned religious intent. The fourth-century political strategist Kauṭilya clarified the distinction between justifiable religious self-destruction and the sin of secular suicide. Those unfortunates who succumbed to despair because of disruptive emotions were denied funeral rites. Their bodies were exposed at the crossroads, where they were subject to the pollution of scavenging animals. Anyone who performed funeral rites for a suicide would be himself deprived of funeral rites. Any Brāhman[25] who associated himself with those forbidden rites would forfeit his privilege of conducting sacrifices, teaching, and giving and receiving gifts.[26]

Self-destruction that did not involve turbulent emotion was sometimes acceptable. Three examples illustrate types of self-killing that were permissible because they did not create karmic disorder. An enlightened sage was thought to be passionless; his unemotional abandonment of the body was thus without karmic consequence. Because he was acting according to his dharma, or righteous behavior, the warrior who died while performing a kṣatriya ritual[27] or on the battlefield, no matter how seemingly rash or imprudent the act, was also exempt from the stigma of suicide.

An older person who had fulfilled life’s duties and was no longer able to keep the rules of Hindu orthopraxy was also allowed to take his life. The legendary sage Atri wrote that an old person who cannot conform to the rules of bodily purification or is beyond medical help may abandon the body and still have purification rites performed and the Hindu funerary rites of śrāddha[28] offered for his salvation.[29] Doubtless the ideal here was the notion that an older person, or someone with unusual spiritual maturity gained through arduous religious discipline, had the necessary emotional discernment to abandon life without karmically disquieting sentiment. Such a death was not considered suicide, but the recognition of the futility of a life that cannot conform to Hindu orthopraxis.

Even though emotion was presumably involved, suicide also could be used for the absolution of sin, and if this were the case, no opprobrium was attached to the act; on the contrary, the sin was absolved, and the self-destruction was viewed as heroic. According to the Āpastambīya Dharma-sūtra, criminals could expiate their sins through various imaginative forms of self-destruction. Marco Polo mentions that in the thirteenth century an Indian criminal who was condemned to capital punishment was entitled to stab himself to death for the love of his gods.[30] The criminal was thus allowed to transform his inevitable death sentence into a meritorious act of self-oblation. The inevitability of his death made the criminal’s self-sacrifice an acceptable self-destruction. Individuals who performed penitential abandonment of the body were cleansed of all guilt and were allowed śrāddha funeral rites.

If it is assumed, on the basis of the Pallava inscription, that the self-oblations performed at Mallam were dedicated to men who chose to self-decapitate themselves in honor of the goddess, it must also be assumed that the men who are depicted in the process of self-decapitation in the Mallam sculptures fell into one of the categories of permissible religious self-destruction. If not, they certainly would not have been the subjects of honored hero memorials. It is likely since the stones are surrounding a temple dedicated to the god of war, and a deity especially honored by the kśatriya caste, that the sacrificers were making self-oblation for the benefit of the stability of the king and his kingdom, whether for an heir, victory in battle, or relief from a disease affecting the kingdom.

Divinities Who Receive Sacrifice

Although the memorials are found near a Subrahmaṇya temple, the inscribed Pallava period hero stone at Mallam records self-oblation to a goddess. Kings ruled with their śakti,[31] their tutelary goddess, and she had to be appeased with blood. Like human mothers, goddesses can be nurturing, creative, and giving, but they also have the capacity to wound, rend, and destroy. They need the energy generated by blood sacrifice to renew their powers of creation. Indian goddesses are the mistresses of the dark side. They deal with the messy aspects of existence: birth, blood, sexuality, decay, disease, warfare, old age, and death. Indian religion is peopled with many dangerous goddesses in both the “great” and “little” traditions. These are the deities who drink the blood of the battlefields, cause the pustules of smallpox, and steal the breath of the newborn. These are the divinities who most often demand propitiation and homage, usually in the form of self-oblation.

Head sacrifice was greatly honored at certain periods in Indian history. Asko Parpola proposes that head sacrifice to goddesses may be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization (2500–1750 BCE), as evidenced by a sacrifice scene on the Fig Deity Seal.[32] Documentation of the Śaṅgam[33] period attests to its early history in the Tamil region. Head offering references are abundant in South Indian literature from the sixth century, and there are numerous sculptural examples depicted on seventh-century South Indian temples.[34]

The sculptural representations of head sacrifice at Pallava, Cāḷukya, Paṇḍya, and Cōḷa sites attest to its common practice in South India. The practice was noted not just on hero stones but incorporated into the formal iconographic programs of large temples. Three examples can be seen at Mamallapuram alone: in the Draupadī Ratha, in the Varāha Maṇḍapa, and on the north wall of the Shore Temple. The subsidiary sacrificing figures surrounding the Durgā devakōṣṭha (the architectural image niche) in many Cōḷa temples—such as those at Kuhur, Pullamangai, Cakrapalli, Konerirajapuram, and Punjai—are evidence of the inclusion of head-sacrifice imagery into the iconographic programs of Cōḷa temples. Examples at Kunnakkudi and Tiruchirappalli indicate that the rite was patronized in the Paṇḍya region as well. Early Western Cāḷukya sculptural evidence on the Durgā devakōṣṭha at the eighth-century Virūpākṣa temple at Pattadakal as well as an inscribed memorial stone from the Kalyāṇī Cāḷukyas indicate the practice also occurred in the Southwest (fig. 3).

Head sacrifice in this early period was made to honor the goddess and, by extension, to support the monarch by ensuring the grace of the goddess (his śakti) on the king’s behalf. Ancient South Indian kings ruled with the support of their tutelary śakti, but this alliance, like a human marriage, needed constant nurture. The pre-Sanskritized Goddess of South India was a fierce deity who claimed fearsome propitiation. With the gradual inclusion of goddess worship into the Great Tradition, most violent and erotic aspects of goddess worship were edited out, creating a pacific vegetarian puja.[35] The violent and erotic aspects would only reemerge in the potent symbolism of Tantric Śākta religion.[36] An example of the incorporation of tribal goddess worship into Hindu Tantra may be seen in the worship of the Tamil war goddess Koṛṛavai, whose identity eventually merged with Durgā.[37]

Like Durgā Vindhyavāsanī, who represented the limits of ancient North Indian society and geography,[38] Koṛṛavai was said to inhabit the margins of both society and geography: she was a goddess of the warrior tribes, and she inhabited the desert and the forested hills of South India. Her temples were described as deep in the forests and protected by ghosts and ghouls.[39] Head-offering rituals to Koṛṛavai were described in early Tamil literary sources, such as the grammatical work the Tolkāppiyam (circa 200–450), the fifth-century epic poem, the Cilappatikāram, and the sixth-century Buddhist text the Maṇimēkalai.

Koṛṛavai was a warrior/mother goddess, her gaping maw ready to consume the bodies of her slain children. Śaṅgam war practices included a post-battle “field sacrifice” (kalavēḷvi) to Koṛṛavai. The rite gave thanks to the goddess for her support and washed away the stain of violent bloodshed. The medieval Tamil commentator Nachchinārkkiniyar reported that the sacrifice was performed by collecting the bodies of the enemy and boiling them in a great kettle supported on their own severed heads. He equated this sacrificial offering to the poṅgal[40] offering: just as the gods were offered the first grains of the harvest, the goddess was offered the yields of war.[41]

Early Tamil literary sources describe blood and head sacrifices to Koṛṛavai.[42] The Cilappatikāram describes a rite in which a virgin was dressed as Durgā. The girl was placed on a stag (the vāhana of Koṛṛavai). People danced in her honor, and then the rite culminated with a warrior’s self-decapitation. His blood was offered to the girl who represented Durgā/Koṛṛavai.[43] In another scene, the Cilappatikāram describes warriors “offering their fierce heads to the sacrificing priest, they cried, ‘The king will return victorious!’ and their dark hairy heads fell upon the altar.”[44] By the Pallava and Cōḷa periods, Koṛṛavai, along with her rites and iconography, had been integrated and then subsumed into the Durgā cult. Integration can be seen in Pallava and Cōḷa temple sculptures, which depict blood sacrifices offered to a composite goddess who displays the attributes of both Koṛṛavai (represented by her vāhana, the deer)[45] and Durgā (represented by her vāhana, the lion).[46]

We might imagine this scene: a nighttime gathering, music, chanting, the press of bodies, and the persuasion of “arena culture”—warriors going to the Subrahamaṇya temple and calling on the goddess Koṛṛavai to give victory to their king and fellow soldiers, then selflessly offering themselves as the first fruits of battle. This would have been perceived as a supremely noble and valorous act, the ultimate form of social altruism.[47] This same scenario could have played out to petition for victory not in battle, but against disease, the goddess’s special venue of control. The later images at Mallam were perhaps less overtly military in intent, and more personal, a petition to Koṛṛavai to prevent epidemics.

Symbolism of the Head

It is possible to commit suicide in many different ways, but to self-decapitate is probably one of the most difficult.[48] So why was this form of self-sacrifice pursued and honored? The symbolism of the head was so resonant and powerful that it impelled individuals toward this particular form of oblation.

The stones at Mallam depict just head and torso; no material was wasted on a full-length portrait. The faces are generic; the bodies athletic and slim, but undistinguishable as individuals. What was being honored was the act of decapitation, not the personal identity of the offerer. The form of self-sacrifice underscores this: the loss of one’s head means an obvious loss of one’s individuality.

As the crown of the body, the head symbolizes the entire individual. As the seat of the mind, it represents rational life, rule, and control. Because of this symbolism, a decapitation implies a loss of power, position, and prestige. In self-sacrifice rituals, the offerer seeks a merger with the divine; decapitation is therefore a specifically ego-effacing act that relieves the offerer of the burden of ego and allows union with the divine.

The head has power as the locus of the soul and the seat of the self. An offerer gave more than his life; he gave the power of his unique and intimate identity. Therefore, self-decapitation represented submission to the deity and the rejection of self before the greater reality of the divine; it graphically displayed the void of self and the realization of nonattachment to self. On a more pragmatic level, a decapitation represented the loss of power and the transfer of that power to the divine recipient of the sacrifice.

In addition, the head is laden with sexual symbolism.[49] Many ancient Indians, like the Greeks, Romans, Jewish Kabbalists, and medieval Christian alchemists, believed that semen was stored in the head.[50] Sexual vitality was proportionate to the length and luxuriance of one’s hair. Hair piled high symbolized the rich store of semen that the Hindu ascetic controlled through his austerities. Cutting the hair of a Hindu ascetic would result, as it did with Samson, in a loss of virility and control. The touching of another’s head and hair carried a message of sexual intimacy, and the hair and head often are associated with the sex organs.[51] Therefore in Indian myth, as in other cultures, a decapitation can represent a symbolic castration or a denial of sexuality.[52] Many sculptures show the oblate holding up his head by his long hair, knotted in a chignon, and striking his exposed neck with a short-bladed sword.

Both bhakti and Tantra espouse patterns that rely on the displacement of erotic identification with the divine. The denial or destruction of sexual identity is desirable in the system of bhakti where a male devotee identifies with the goddess as lover/beloved and child/mother. In theory, Tantric mokṣa[53] is obtained when the seed is brought up from the sexual organs and along the spinal column, through the cakras[54] to be released at an aperture at the top of the head.[55] Correspondingly, death by beheading often has an element of erotic release in Indian myth, especially in examples involving the goddess. While copulating with the corpse of Śiva, the goddess Kālī holds a severed head. She is able to engage the dead god in sex, because like the separated head, his analytical life is cut off and becomes passive in contrast to his active phallus. So too the self-beheaded goddess Chinnamastā is depicted in paintings as drawing power and stability from the sexuality of the copulating lovers under her feet.

An example of the erotic ascetic duality, and certainly one of the most pervasive images of decapitation/castration, is exemplified in the story of the goddess Durgā and the buffalo demon Mahiṣa. Much of the banter between the goddess and the demon in the Devī-Bhāgavata Purāṇa is erotically charged. The goddess is uninterested in Mahiṣa as a lover, but Mahiṣa is hopelessly besotted with the beautiful goddess. In most versions of the myth Mahiṣa expects a battle that will end in sexual conquest. Instead, it ends in a series of emasculations, until the demon is finally killed in mid-transformation between animal and human.[56] In late Purāṇic interpretations, Mahiṣa became the ideal devotee, ready to transform himself into any form to find union with the divine.[57]

The relationship of the goddess and the demon is sometimes analyzed as a metaphor for the relationship of the goddess and the bhakta. In this interpretation, it is better to have union in death with the divine than no union at all, and death provides a final and complete annihilation or absorption into the Great Mother, the matrix of the Mahādevī.

The Eroticism within Religious Asceticism

The myth of Durgā and the buffalo demon addresses the inherent, but oblique, element of eroticism concealed within many forms of religious ascetic devotion. It is part of many ascetic movements that are ostensibly concerned with the control of the sensuous passions. The Spanish mystic and ascetic reformer of the Carmelite order Teresa of Ávila wrote of her vision of Christ in a way that left no doubt about both the masochistic and the erotic:

In [the hands of an angel] I saw a long golden spear and at the end of the iron tip I seemed to see a point of fire. With this he seemed to pierce my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he drew it out I thought he was drawing them out with it and he left me completely afire with a great love for God. The pain was so sharp that it made me utter several moans; and so excessive was the sweetness caused me by this intense pain that one can never wish to lose it, how will one’s soul be content with anything less than God. It is not bodily pain, but spiritual, although the body has a share in it—indeed a great share.[58]

When carving his sculpture The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa in Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) seemed to have no doubts about the erotic nature of Teresa’s painful but exquisite visions. Hindu offerers also approached the goddess with a passionate adoration akin to the ecstasy described by Saint Teresa. Devotion and sensuality are often closely linked. Tantric Hindu practices certainly acknowledge this, an apparent contradiction that also is incorporated in the many erotic/ascetic paradigms in Indian myth. Lord Śiva, the “erotic ascetic,” is the ultimate model for this dichotomy. Śiva is both the aloof and remote ash-covered ascetic and the passionate lover of Umā. This seemingly contradictory aspect of asceticism can be effectively eliminated with the symbolic destruction of sexual identity effectuated by decapitation.

Historic Factors for Self-Oblation

Let us consider the ninth-century Pallava memorial in its historical context. The tradition, already in place, of sacrifice to war goddesses such as Durgā/Koṛṛavai may have given rise to the desire for this oblation, but there may have been more personal factors—such as the expiation of sin, an illness that prevented adherence to Hindu dietary or ritual laws, or the chaos and social breakdown surrounding a famine or pandemic.

During the Pallava period, innovations in Hindu bhakti devotionalism were evidenced in the rise of the twelve Vaiṣṇava Āḷvārs and the sixty-three Śaiva Nāyaṇmārs. These groups of saints were of immense importance in the development of South Indian piety. The saints came from many different occupations and castes; their hymns and deeds became bhakti paradigms of devotional surrender. Some of these saints were of proven historicity, but others appear to have been purely mythic.[59] Their extravagant devotion must have had great impact on society and served as archetypes of grace, piety, and self-abnegation.

Stories and images of the Āḷvār and Nāyaṇmār saints attest to the extremes of devotion that were offered as widely known paradigms. South Indian stories attest to these bhakti saints’ self-giving love of God. They called themselves Slaves of the Lord, implying that they belonged to God, body and soul. Nāyaṇmār bhakti stories, such as the tale of Ciṛuttoṇṭar, who sacrificed and fed his child to Śiva, make it clear that the gods were entitled to ask the most fearsome sacrifices of their devotees, even human sacrifice.[60] Other stories related various forms of self-mutilations and self-sacrifices, such as those of Kaṇṇappa, who gave his eyes to Śiva[61]; Arival-Taya Nāyaṇmār, who was about to decapitate himself with a sickle before Śiva intervened[62]; Kanampullar, who pulled out his own hair so it could be used as temple lamp wicks[63]; and King Pugal Cholar, who killed himself in remorse for the death of a Śaiva devotee.[64]

At the same time that bhakti encouraged radical forms of dedication to the gods, the Tantric practices of the Kāpālikas, Kālamukhas, and Pāśupatas cults developed socially transgressive expressions of that devotion. There is ample evidence from contemporary literary sources, such as the Tevāram cycle of poems and the Mattavilāsa, that Tantric sects flourished in ancient South India. Certain sites, such as Kanchipuram, Mayilapur, Kodumbalur, and areas of Thanjavur, are mentioned in literature as having been associated with Tantric sects dedicated to either Durgā/Koṛṛavai, in her angry or ugra aspects, or to the terrible form of Śiva Bhairava.[65] Tiruvarur is referred to as the location of the goddess who demanded animal and human sacrifice. It is alleged that the Vedāntic philosopher Śaṅkara (circa 788–838) visited Tiruvarur during the Pallava period and subdued the goddess by closing her mouth and throwing her image down a well.[66] However, sculptural evidence from the Cōḷa period indicates that the idea of self-sacrifice in the form of self-decapitation continued or was reinstituted at the shrine after Śaṅkara’s visit. Sculptural evidence at other sites—such as Mamallapuram, Kanchipuram, and Tiruchirappali—indicates that self-sacrifice took place to honor of the goddess during this time, so if Śaṅkara did have success with the eradication of extreme forms of Tantric goddess worship, his reforms were short-lived.

Tamil culture during the Pallava period offered a fertile ground for the type of zealous devotion memorialized in the early Mallam stones. The Pallava reverence for the monarch was expressed through devotion to the king’s śakti. The human male and the divine female joined to form a sacred political state. At the center of the state (or maṇḍala), the king and śakti created an axis for religion, politics, and war. We can see this expressed in architecture and sculpture in the Varāha and the Ādi Varāha shrines at Mamallapuram, where king and goddess are portrayed in idealized metaphoric images.

Military culture expressed exceptional veneration of the king as charismatic leader. A rising emotionalism within the bhakti tradition, coupled with Tantric socially violative radicalism, created an atmosphere conducive to self-sacrifice in honor of both king and goddess. It is evident that, at least in the practice of head-offerings, the Pallavas were eager to emulate the military and religious ethos of indigenous Tamil culture, where loyalty and devotion to one’s king and chosen deity were expected. The Pallavas suffered from almost constant warfare with the neighboring Cāḷukyas, and this pervasive social uncertainty, coupled with outbreaks of famine and epidemic disease, must have contributed to a perceived need for supporting sacrifice.

Although the Pallava stone is the only dated and inscribed stone from Mallam, the greater number of the Mallam memorials may be tentatively linked by differences in style to later Teliṅgāṇa patrons. These later patrons may have been from the Kākatīya Kingdom (circa 996–1323), comprising a large part of what is now Andhra Pradesh; the Reḍḍi Kingdom (feudatories of the Kākatīyas, circa 1040–13th century), ruling an area from Srisailam to the Bay of Bengal; and the Vijayanagara Empire, encompassing a large part of the southern Deccan plateau. It is likely that most of the later stones were produced after the mid-fourteenth century for patrons reacting to distinctive new patterns in Hindu devotionalism, which in turn stemmed from profoundly disturbing social-biological upheavals.

The later stones are noted for the following distinctions in style: the oblate is shown standing, rather than genuflecting or kneeling, as is the case with self-sacrifice representations from the Pallava and Cōḷa periods. The devotee is no longer depicted in profile, but squarely faces the viewer. He is no longer shown post-sacrifice with a headless trunk, head improbably held aloft. In the middle period, he is shown in the process of sacrifice, holding his head up by his knotted hair, with the short-bladed sword cutting the back of his neck. In the later period, the oblate holds, with both hands, a double-bladed sword to the back of the neck. Presumably this type of “mezzaluna” blade was developed for just this purpose. In contrast to earlier examples from the Pallava or Cōḷa periods—where the oblate is shown in profile, or the torso is in profile and the head removed—these later images have a more direct confrontational style. The devotee seems to look out unswervingly at the viewer in triumph and perhaps in challenge, as if caught by the artist just before his death.

The fourteenth century was often a difficult and depressing time for the Hindu kingdoms. The Muslim Delhi sultāns defeated the kingdoms in a series of invasions and then systematically plundered the royal treasuries and the vast wealth of their temples. In 1323 the Kākatīya king Pratāparudra committed suicide on the banks of a holy river rather than submit to the dishonor of a Muslim capture and incarceration. Five years later King Kampilideva fell in battle after overseeing the post-defeat immolation (jauhar) of his women. The triumphant Malik Zāda, a minister and a general of the Delhi sultān Muhammad-bin Tughlaq, announced his victory by sending Kampilideva’s straw-stuffed, severed head to the sultān. By 1336 all the South Indian Hindu kingdoms except the Hoysalas had been defeated and their territories annexed by the Delhi Muslim Sultanate. (The last Hoysala king, Veera Ballala III, was killed in 1343 at the Battle of Madurai.) However, 1336 also saw the establishment of the Vijayanagara Empire by Harihara I and his brother, Bukka Raya I, which offered Hindus political hope and a chance to rekindle their religious life.

These military disruptions in South India resulted in extreme social upheaval and famine. The population, weakened by war and starvation, was devastated by the bubonic plague pandemic of the mid-fourteenth century. This plague was the same virulent Black Death that later devastated Europe from 1346 to 1350.[67] Before the trading port of Messina, Sicily, was struck in 1346–47, Europeans had heard rumors that entire regions in India had been depopulated by plague, but only fully understood with dismay when the same pestilence wiped out entire European villages in a few days.[68]

The Moroccan explorer and diarist Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (1304–1377) gave horrifying eyewitness accounts of the swift, devastating nature of this disease in South India. He visited Madurai during the first outbreak of the Black Death in 1345 and vividly described the exceptional virulence of a disease that could kill in a matter of days or even hours.[69] “When I reached Madura [Madurai], I found that an epidemic was raging there and that the people afflicted with it died in no time. Whoever caught infection died on the morrow, or the day after, and if not on the third day, then on the fourth. Whenever I went out I saw people but diseased or dead.” [70]

The creator of a scale for measuring the impact of disasters, Canadian geographer Harold D. Foster, posits that world calamities should be ranked not just in terms of lives lost but also by emotional stress and social upheaval. On the Foster Scale, World War II ranks first; the Black Death, second; and World War I, third. John Kelly points out that U.S. Atomic Energy Commission found that the Black Death comes closest to mirroring all-out nuclear war “in its geographical extent, abruptness of onset and scale of casualties.”[71] Although people and cultures react differently to calamity, it would be absurd to think that such anguish would not have a direct effect on fourteenth-century religion and art. It has long been accepted that the Black Death had a profound impact on religion, social structure, and economics. The effects of the plague also destabilized the arts in Europe: the development of painting styles were affected, perhaps delaying and changing the pattern of the Renaissance itself.[72] It is time that medical history be put in the service of Indian art as well, and that we consider the frightful impact of devastating diseases on the development of style and subject matter, including religious self-expression in the arts.

The malignancy of the Black Death was all the more terrifying because its victims were ignorant of its cause and seemingly helpless to find its remedy. When life devolves into a daily uncertainty of warfare, famine, and disease, patterns of religious expression are transformed from abstract formality to urgent petition. The plague in India, just as in fourteenth-century Europe,[73] had a profound effect on fanatical patterns of religious devotion, but in India the stresses of the plague were compounded by religious persecution and military devastation.

The Muslim control of the Deccan did not last. In the mid-fourteenth century the troops of the Delhi Sultanate were recalled from South India to fight in other wars, and local Hindu chiefs began to declare their authority. With the establishment of the Vijayanagara Empire, a Hindu renaissance began on the Deccan. Unfortunately, it was not a peaceful period. Vijayanagara was forced to contend with rival Hindu kingdoms as well as the Muslim armies of the Deccan Bahmani Sultanate, but despite the near constant warfare, the Vijayanagara Empire created a rich Hindu society and a bulwark against Muslim cultural aggression.

The Vijayanagara rulers were deeply devout and were unstintingly munificent in their patronage of Hindu religious life and art, but the economic, biologic, and social aftermath of warfare, famine, and disease precipitated lasting changes in Hindu devotional practice. Both bhakti, with its emphasis on a development of a charismatic relationship between devotee and the divine, and Tantra, which emphasized the integrative and socially contravening forms of anti-orthopraxy, were already present in Hinduism. But after the disasters of the fourteenth century, bhakti and Tantra gained even more adherents seeking new forms of spiritual salvation.

Earlier Indic religion, which emphasized complex and costly sacrificial rites and rituals, had appealed to the priestly and ruling classes. Its elitism and concern with control, manipulation, and consolidation of power through the precise recitation of Sanskrit ritual chants did not include those members of the population outside of the upper echelons of society. Non-Sanskritized worship such as charismatic devotionalism grew to accommodate those liminal members of the population. Gradually these non-Vedic forms of devotion evolved into more formalized types of bhakti and Tantra.

The pervasive use of imagery in bhakti practice reflects a type of Indian religion reliant on image rather than word. The contemplation of image (darśan) evokes sympathy and empathy in the viewer. It gives the devotee an emotional space in which to find communion with the divine without the need for a priestly intermediary. For a predominantly illiterate society, the hero stone offered an exemplar of noble devotion, accessible to anyone, regardless of social privilege.

With the traumas of the fourteenth century, there was a need to identify and consolidate beleaguered Hindus and to accommodate and assimilate previously marginalized groups under the rubric of Hindu or at least non-Muslim identity. The veneration of the body, implied by the sanctification of the sacrificed individual in the hero stone, was a step away from literate upper-caste privileged practices. Previously, the body was perceived as an inherently polluted object and the lower the caste, the more polluted. With the veneration of heroic acts memorialized by hero stones, the body became a new basis for understanding and manipulation of the devotee’s relationship to god. It was an affirmation of the individual’s body over the privilege of caste, learning, and literacy.

Under the medieval Hindu renaissance Tantrism emerged as a dominant force because its integrative approach to worship and non-elitist attitudes appealed to a broad social spectrum of the population. Tantric bhakti encouraged the practice of vow-making (vrata) and religious gift-giving (dāna), which created contractual relationships between the worshipper and the gods. Many Hindus rejected the formalities of the traditional yajñas (sacrifices) and turned to various religious vows as forms of devout expression, which were more intimate and reciprocal. Because these vows were open to all Hindus, regardless of caste or social privilege, they helped to mitigate the differences between the three upper castes, and worked to unify besieged and traumatized Hindus as identifiable joint participants in a particular and shared religious life.[74] Through this transformation of religious access, the body (any body, not just an upper-caste body) became a powerful organ of religious transcendence. Often sacrifices became like-for-like, such as head sacrifices by Kāpālika tantriks that commemorated Bhairava’s decapitation of Brahma.[75] This brought the devotee into the arena of divine emulation where the oblate played many roles: devotee, divinity, sinner, and victim.

Self-sacrifice was thus reconfigured from a distinctive form of self-offering to benefit the king and his śakti to an intimate oblation that would bring merit to the individual only as the result of his personal and contractual vrata with the deity. This transition can be perhaps be ascribed to the sculptures at Mallam, where the early Pallava stone records the benefit of the sacrifice accruing to the king, and the later stones indicate, through their un-inscribed informality, that the benefit accrued to the individual offerer and thus was a personal offering rather than a politically linked event.

Traditions emerging from this period reflect these more personal concerns in religious life. We see, for example, in the devotional songs, or kirtans, of the Varkari movement a stress on the individual relationship between god and devotee. Both the god and the worshipper are asked to perform the utmost in self-abnegation and self-giving. The intimacy of the body in worship is privileged over literacy.[76]

Gradually, a number of South Indian temples accommodated self-offering vratas. Many medieval Śaiva and Śākta temples in South India during this period were noted for their self-sacrificial rites. Those worshippers with a religiously masochistic bent were offered a variety of forms of devotion. In addition to offering blood, limbs, eyes, or heads, devotees could jump into pits of burning charcoal or suspend themselves in slings over pits of upward pointing arrows, and then cut the slings.[77] The temples, called champuḍugullu in the Siṁhāsana-dvātriṁṣika, were staffed by priests who specialized in performing mutilations for those who wished to offer parts of their bodies.[78] The Mallikārjuna temple at Srisailam, for example, had special halls dedicated to the practice of self-mutilation and self-sacrifice. The Hall of the Heroes’ Heads, erected by King Anavemā Reḍḍi in 1377, was an example of how governmental patronage efforts were lavished upon the support of self-sacrifice. The king also built a separate pavilion for heroic self-immolation. The inscription from the Vīraśiro Maṇḍapa (The Hall of the Heroes’ Heads) states:

How wonderful it is that here in this Maṇḍapa hosts of Ekāṅgavīras, who proudly make a votive offering of their eyes, hands, heads and tongues, by cutting them off, attain instantaneously a brilliant body of blessed limbs. The next moment, endowed with three eyes, ten arms, five faces, and five tongues, they shine as if they were aṣṭamūrtis [eight-bodied Śivas].[79]

The Mallam temple, too, may have developed into such a locus for self-offering. Given the large number of memorial stones at the site, it is reasonable to assume that this was the case, and the stones currently arranged about the exterior of the temple enclosure are the only sustaining reminders of a now-vanished practice of complete self-abandonment and consecration to the divine.

Was this self-destruction a useful and ethical form of transcendent worship? We must leave deeper speculation to philosophers,[80] but we also can consider these expressions within their historical cultural spheres. These sculptures are startling to us and cannot be simply dismissed as unusual or peculiar; their sheer numbers demand that they be understood with careful assessment of historical religious developments, including expressions of piety, art, persecution, war, famine, and disease.

Within their historical moment, the oblates who gave their lives pleased the gods, pleased society, and reached liberation or mokṣa. We look at these images from the modern perspective of self-regard and self-preservation and are curious about what could have formed the foundational beliefs for these actions. As bhakti encouraged personal charismatic interaction with the gods, death must have been viewed as a vehicle of transcendence and an opportunity for merger with the divine.

And he who leaves this body and departs from this world remembering me in his last moments, comes into my essence. There is no doubt of that.

—Bhagavad Gita, chapter 8, verse 17

Notes

Female devotees were also among self-offerers, and their decapitations were recorded and honored at sites such as Nalgonda in Andhra Pradesh. P. A. Sreenivasachar, “A Note on Medieval Sculpture in Hyderabad Museum Depicting Self-Immolation,” Andhra Pradesh Archaeological Series, no. 15, The Archaeological Bulletin, no. 2 (Hyderabad, 1963), 26–32.

This stone is inscribed as follows: Of Śrī-Kampuramaṉ (i.e., Kampavarman), twentieth year. To [Pa]ṭṭaipō[tta]ṉ. Proclaiming (literally: having said) the excellent penance (tavam = tapas) desired/made/endured by Okkoṇṭanākaṉ Okkatintaṉ Paṭṭaipōttaṉ, (this) is the gift/honor (paricu) endowed (literally: put) by the ūrār (i.e., leaders of the village assembly) of Tiruvāṉmūr for him (i.e., OOP) who, having given the nine parts (navakkaṇṭam) to Bhaṭārī and having cut his head ... (kuṉṟakattalai), offered (literally: put) (them) on the piṭalikai (i.e., the altar). Having beaten the drums of our village, those who made a stone mound are those who give for his soul. The landowners/lords of Pōttaṉam gave land in Toṟuppaṭṭi (the hamlet of the herds of cows). The one who says that it is not so he will experience (literally: enter) into the sin (pāvam) done by he who does seven hundred murders in-between Kaṅkai (i.e., Gaṅgā) and Kumari (i.e., Kanyākumāri). (Moreover), the one who says that it is not so will get (literally: suffer) a fine of a quarter poṉ to the then ruling king; South Indian Inscriptions 12, no. 106 (1906). T. V. Mahalingam, Inscriptions of the Pallavas (New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research, 1988), no. 226.

The site was mentioned in the 1906 epigraphical survey report South Indian Inscriptions. At that time the site was of interest for its inscriptional material and not the sculptural remains. No survey mention was made of the eighteen other stones now at the site. The whereabouts of the inscribed Pallava stela mentioned and illustrated in the 1906 report are currently unknown.

Purāṇic, referring to the Purāṇas, a set of texts detailing the exploits of the Hindu gods and goddesses. They range in date from the fifth century BCE to circa 1500 CE.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, Volume 3: The Guermantes Way, trans. Charles Kenneth Scott-Moncrieff, Terence Kilmartin, Dennis Joseph Enright (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 494.

Chinnamastā is also worshipped in Tantric Buddhism as a personification of ego extinction.

Reiko Ohnuma, Eyes, Head, Flesh, Blood: Giving Away the Body in Indian Buddhist Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

A number of scholars have tried to configure these self-sacrificing images, such as those at Mamallapuram, as primarily symbolic blood offerings representing the extinction of the ego rather than complete self-oblations, arguing that these images are metaphoric and not actual memorials to religious suicides. See, for example, Dennis Hudson, “The Ritual Worship of Devi,” in Devi: The Great Goddess: Female Divinity in South Asia (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1999), 73–98.

Dehatyāga (Sanskrit): “body abandonment,” with the implication of a spiritual abandonment of the corporeal mass.

This goddess was known by various names, such as Pidāri and Paṭāri. S. Swaminathan, The Early Cholas: History, Art and Culture (Delhi: Sharada Publishing House, 1998), 138.

South Indian Inscriptions, annual report of 1908, no. 498, pl. VI.

Benjamin Lewis Rice, ed. and trans., Epigraphia Carnatica: Inscriptions in the Shimoga District, part 2, vol. 8 (Bangalore: Mysore Government Press, 1904), Sb. 479.

Benjamin Lewis Rice, ed. and trans., Epigraphia Carnatica: Inscriptions in the Bangalore District, vol. 9 (Bangalore: Mysore Government Press, 1905), Cg. 28.

R. Nagaswamy, Tantric Cult of South India (Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1982), 26.

Bhakti is the charismatic and intensely personal devotion to the Hindu gods and goddesses that developed as a result of the personalized depictions of the deities in texts such as the Bhagavad Gītā and the later specialized texts such as the Purāṇas.

Romila Thapar, “Death and the Hero,” in Cultural Pasts: Essays in Early Indian History (Delhi: Oxford Paperbacks, 2003), 680–95.

Tantra, meaning “loom” or “warp,” was the heterodox weaving together of many beliefs into a socially transgressive tradition that challenged the control of orthodox Brāhamanical Hinduism.

John Norris, “East or West? The Geographic Origin of the Black Death,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 51 (spring 1977), 2; Sheldon Watts, Epidemics and History: Disease, Power and Imperialism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 4.

The estimates of deaths are controversial, most recent estimates increasing the numbers previously estimated. Suzanne Austin Alchon, A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), 21.

Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss, Sacrifice: Its Nature and Functions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Midway Reprint, 1964), 13.

G. Bühler, trans., The Laws of Manu, chap. V, 89, in Sacred Books of the East Series, vol. 25, ed. F. Max Muller (1886; repr. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1988), 184.

Friedrich Otto Schrader, ed., The Minor Upaniṣads, vol. 1 (Madras: Adyar Library, 1912), 39, 390ff.

Brāhmans were the first of the four castes. They controlled the rites and rituals of Vedic religion and still exert a huge influence within orthodox Hinduism.

Shama Sastry, ed., Arthaśāstra of Kauṭilya, chap. IV, 7. Quoted in Upendra Thakur, The History of Suicide in India: An Introduction (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1963), 53.

Kṣatriyas represented the second of the four Hindu castes. They were traditionally the warriors, generals, princes, and kings of ancient India.

Śrāddha rites were the formal Hindu funerary/memorial rites performed annually by Brāhmans, which offered gratitude to the offerant’s deceased ancestors, especially parents.

Atri Smrti, 214–15, cited in H. von Stietencron, “Suicide as a Religious Institution,” Bhāratiya Vidyā 27, nos. 1–4 (July 1969), 13.

Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, trans. William Marsden and Thomas Wright (New York: The Orion Press, n.d.), 287.

Śakti means “power”; it is a feminine noun and can be used in the everyday sense of electrical power, but it also can imply a divine power or the embodied goddess that supports the stability of a king.

Asko Parpola speculates that an Indus seal represents the earliest image of head-offering. Asko Parpola, “The ‘Fig Deity Seal’ from Mohenjo-daro: Its Iconography and Inscription,” in South Asian Archaeology 1989, ed. Catherine Jarrige (Madison, WI: Prehistory Press, 1992), 227–36. The seal, as is typical of all Indus seals, is extremely small, and therefore it is difficult—without other corroborating sources, such as a reliable translation of Indus religious writing—to say with absolute certainty exactly what is being depicted or even if the object under discussion is a head.

Śaṅgam period: a historical period in ancient South India, dated circa third century BCE to fourth century CE, noted for its poetry and drama.

There are, however, no South Indian hero stones predating the reign of Dantivarman Pallava (circa 796–846).

Pūjā: the daily, usually individual and personal, worship of a Hindu deity.

Śākta religion was a form of Hinduism focused on worship of the goddess, often in one of her violent forms.

T. V. Mahalingam, “The Cult of Śakti in Tamilnad,” The Śakti Cult and Tara, ed. D. C. Sircar (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1967), 19.

David Kinsley, The Sword and the Flute: Kālī and Kṛṣṇa: Dark Visions of the Terrible and the Sublime in Hindu Mythology (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1975).

K. A. Nilakantha Sastri, Sangam Literature: Its Cults and Cultures (Madras: Swathi Publications, 1972), 70.

Poṅgal is the Tamil New Year/harvest festival celebrated in late winter or early spring.

N. Subrahmanian, Śañgam Polity: The Administration and Social Life of the Śañgam Tamils (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1966), 162–63.

In 1904, V. Kanakasabhai described this goddess as Kālī, a term that is often used generically to describe a warlike goddess. V. Kanaksabhai, The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago (1904; repr. Madras: South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society, 1956), 228.

Prince Ilango Adigal, “Vettuvavari,” canto 12, Shilappadikaram, trans., Alain Danielou (New York: New Directions, 1965), 76–85.

James C. Harle, “Durgā, Goddess of Victory,” Artibus Asiae 26, nos. 3/4 (1963), 237–46.

Mary Storm, Head and Heart: Valour and Self-Sacrifice in The Arts of India (New Delhi: Routledge, 2013).

A lever-pulley decapitating device is illustrated on a hero stone from Vijayanagara, located to the north of temple NN z/2. The hero’s head was tied to a lever; when the hero pulled the lever with his left hand, it would jump up, and his head would be cut off by the sword he held in his right hand. Anila Verghese, Religious Traditions at Vijayanagara: As Revealed Through Its Monuments (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1995), 95.

G. M. Carstairs, The Twice Born: A Study of High-Caste Hindus (London: The Hogarth Press, 1957), 84, 78. This idea was not unique to India. Michael Meslin, “Head Symbolism and Ritual Use,” in The Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 6, ed. Mircea Eliade (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 221.

Wendy Doniger, Splitting the Difference: Gender and Myth in Ancient Greece and India (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1999), 227.

P. Hershman, “Hair, Sex and Dirt,” Man: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, n.s., vol. 9. no. 2 (1974), 274–98.

Decapitation is a common symbol of castration in myth, dreams, and fantasies. Sigmund Freud, The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. and ed. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1957), vol. 21, 207; vol. 14, 339; vol. 16, 268.

Mokṣa: spiritual liberation or release from the cycle of endless rebirth.

Cakras: six points along the human body that are associated with various forms of physical and spiritual energy.

Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, Sexual Metaphors and Animal Symbols in Indian Mythology [Women Androgynes and Other Mythical Beasts] (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1980), 45.

Quoted in Georges Bataille, Eroticism: Death and Sensuality (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1986), 224.

A number of the Nāyaṇmār saints, including a commander-in-chief of the army, Ciṛuttōṇṭar (active circa 642); possibly two monarchs, Siṁhavarman (reigned circa 550–75) and Rājasiṁha (reigned circa 700–28); and four Āḷvār saints came from the Pallava region.

David Shulman, The Hungry God: Hindu Tales of Filicide and Devotion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 20–30.

Vidya Dehejia, Slaves of the Lord: The Path of the Tamil Saints (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1988), 158.

C. Minakshi, Administrative and Social Life under the Pallavas (Madras: University of Madras, 1938), 180–81.

Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Reports on Epigraphy (1911–1914), Madras Epigraphical Reports (Madras: Archaeological Survey of India, Southern Circle, 1912), 68.

Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978), 94.

H. A. R. Gibb, Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa, AD 1325–1354 (1929; repr. New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, 1993), 264–65; Mahdi Husain, The Reḥla of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (India, Maldive Islands and Ceylon): Translation and Commentary (Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1976), 101.

John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: Harper Collins, 2005), 11.

Millard Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 70–73.

Christian penitents believed that the Black Death was the result of God’s wrath visited upon a sinful world. Extremist eschatological cults arose in Europe as a response to the plague. They engaged in various forms of self-mortification in preparation for the Last Judgment. The Brotherhood of Flagellants regularly beat themselves to the edge of death in an effort to purge themselves of the sins believed to be responsible for the disease. Robert E, Lerner, “The Black Death and Western European Eschatological Mentalities,” The Black Death: The Impact of the Fourteenth-Century Plague, ed. Daniel Williman (Binghamton: State University of New York, 1982), 77–105.

M. Somasekhara Sarma, History of the Reḍḍi Kingdoms (Circa 1325 to Circa 1446 A.D.) (Waltair, India: Andhra University, 1948), 323–24.

In an astonishingly intimate expression of physical devotion, the fourteenth-century Varkari poet Janabai recites:

One day I went to batheThere was not enough water to mixGod came running, gave me cool waterSaying “Here you are,”Mixed it with his own handsPoured it over Jani, over my hair.He washed my hair well, saying:“Sit still, I’ll do it.”Jani says, like a motherHe plaited my hair with his own hands.Ruth Vanita, “Three Women Saints of Maharashtra: Muktabai, Janibai, Bahinabai,” in Women Bhakta Poets, ed. Madhu Kishwar (Delhi: Manushi Publishing, 1989), 52.

R. Chandrasekhara Reddy, Heroes, Cults and Memorials: Andhra Pradesh, 300 A.D.–1600 A.D. (Madras: New Era Publications, 1994), 11.

M. L. K. Murthy, “Memorial Stones in Andhra Pradesh,” in Memorial Stones: A Study of Their Origin, Significance and Variety, ed. S. Settar and Gunther D. Sontheimer (Institute of Indian Art History, Karnatak University, Dharwad and South Asia Institute, University of Heidelberg, 1982), 213, n. 12.

Moshe Halbertal, On Sacrifice (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2013), 63–78.

Ars Orientalis Volume 44

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0044.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.