- Volume 44 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.5mb

Abstract

Eschatological imagery appeared in Persian and Turkish book arts from circa 1300 to 1900. In manuscript paintings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the signs of the hour were closely affiliated with the Prophet Muhammad and the miraculous events of his life, in particular his heavenly ascension. In the sixteenth century, illustrations of otherworldly terrains and events were further developed in pilgrimage guides and books on the conditions of resurrection. These illustrated manuscripts were marked by millenarian anticipation and sectarian debate. By the 1800s, new cosmologies began to provide readers and viewers with exoteric picto-diagrams for meditating upon the esoteric meanings of faith and imagining salvation. In these depictions of the afterlife, the Islamic eschaton is rendered as a set of otherworldly realities that transcends language and thus is best rendered by means of graphic images.

At some point in the unforeseen future and immediately preceding the verses cited above—found in the sura titled “The Darkening” (al-Takwīr)—a series of catastrophic events take place: the sun darkens, stars fall to the ground, mountains tremble, seas boil, the heavens are unveiled, hell is set ablaze, and paradise is brought near. These signs of the hour (ishārāt al-sā‘a) initiate a sequence of reversals of natural phenomena, heralding the coming of final things and the full realization of the Islamic faith (yawn al-dīn). As the Koranic verses describe, at the end of time, the Prophet Muhammad—in what could be interpreted as a state of optical clarity and spiritual clairvoyance—will observe God (“Him”) and many other signs on the clear horizon. Muhammad’s visual perception of the divine and the unseen (ghayb),[2] both in this world and the next, without a doubt suggests an image-laden conceptualization of the afterlife in Islamic religious traditions.

Otherworldly events, places, and beings have been explored by scholars working on the Koran, Ḥadīth (Sayings of the Prophet), tafsīr (exegesis), and Arabic qiyāma (eschatological) literature. However, a systematic study of the depiction of supernatural phenomena, their visual qualities, and symbolic roles within the visual arts of Islam has not yet been undertaken. Extant manuscript paintings produced from the fourteenth to nineteenth century, however, reveal that eschatological imagination played a significant role within the pictorial arts of Islam. The visual evidence transcends literary works composed in Arabic to encompass artistic traditions produced in both Persian and Ottoman cultural spheres.

This study is not intended as a review of the field of Islamic eschatology, although I will use some of its key studies to interpret pictorial representations. Moreover, it does not survey all visual representations of the Last Judgment, heaven, and hell. Only a small selection of paintings are presented here in order to highlight how their main themes and iconographies were developed and altered over the course of several centuries. As will be demonstrated, eschatological motifs were first elaborated in illustrated histories and biographies from circa 1300 to 1500. During and after the sixteenth century, such motifs began to appear in pilgrimage guides, apocalypses, and gnostic-scientific works, which could be subjected to sectarian interpretation. As such, it is clear that pictorial representations of the “signs of the hour” in Persian and Ottoman artistic traditions echoed and sustained intra-Islamic discourses concerned with political legitimacy and religious authority, especially from the early modern period onward.

Before proceeding with a discussion of the visual evidence, it is important to note that this study considers images of the eschaton under the general rubric of “religious iconography.” Indeed, illustrated manuscripts that survive in complete cycles or fragments attest to the many possibilities of invoking the afterlife, heaven, and hell in pictorial—not just textual—formats. These varied images clearly reveal that the eschaton was central to religious thought in Islamic traditions and a source of inspiration for the production of religious imagery, whose roles ranged from the political and moralizing to the directive and didactic.

The Straight Path

The various modes of imaging the eschaton in Islamic painting were inspired by the cultures and religions with which Islam came into contact. From circa 1300 onward, Mongol culture in general, and Buddhism in particular, contributed to the formulation of culture in Islamic Central Asia and Iran under the aegis of the Ilkhanid rulers (reigned 1256–1335). At this time, Central Asian Buddhist imagery inspired Islamic pictorial traditions, in particular those containing eschatological motifs. For example, depictions of angels with fluttering waistbands and demons with flaming brows as found in Islamic illustrated manuscripts may have been inspired by Uighur Buddhist book and wall paintings made in Inner Asia before 1300.[3]

During the Ilkhanid period, the writing of universal chronicles discussing past and present dynasties, lands far and near, and the life of the Prophet Muhammad served as the predominant mode of recording history and picturing the world. Many illustrated manuscripts produced in Persia during the early decades of the fourteenth century—such as al-Bīrūnī’s al-Āthār al-Bāqiyya ‘an al-Qurūn al-Khāliyya (Chronology of Ancient Nations)[4] and Rashīd al-Dīn’s Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles)[5]—offer variant biographies of the Prophet Muhammad while also promoting the superiority of Islam over other religions. The newly converted Mongol rulers of Iran carved out their position in world and religious history through such illustrated compendia. These texts legitimized incursions into Islamic lands, which were described in contemporary Arabic texts as an unfolding apocalypse.[6] As the manuscript paintings suggest, apocalyptical concerns were likewise shared by the Mongols after they embraced Islam and set themselves to the task of following the “straight path” (al-ṣirāṭ al-mustaqīm).

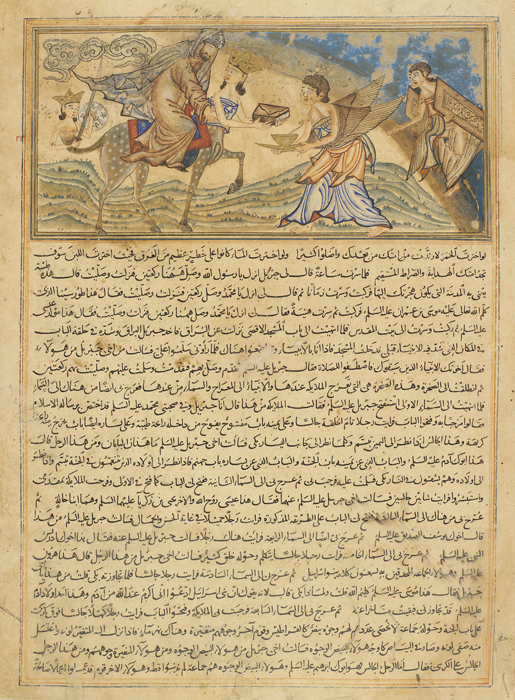

Evidence for Ilkhanid interest in eschatology can be found in one of the illustrated copies of Rashīd al-Dīn’s Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh, produced circa 1306–15 in a large charitable foundation located in a suburb of Tabriz. In the earliest extant manuscript, the life of the Prophet is discussed and illustrated, from the time of his birth to his celestial ascension (mi‘rāj) on al-Burāq, the winged, human-headed flying horse (fig. 1).[7] The painting of the Prophet’s mi‘rāj comprises the earliest surviving depiction of the heavenly ascent in the history of Islamic painting. Here, the cloaked Prophet sits on the back of his steed as he holds on to its square-shaped torso. Burāq’s speckled body resembles that of a horse, its human head bears a crown, its arms hold a closed codex, and its tail has been transformed into an angel bearing a sword and shield. Greeting the Prophet and his steed are two winged angels holding golden cups: the first carries his on a tray, and the second emerges from a door in the blue heavens, which curves upward as if it is the arc of the firmament. This episode can be identified as the “testing of the cups,” when Muhammad selects and drinks milk. Fulfilling an initiatic purpose, Muhammad’s correct choice confirms his prophetic status and enables him to ascend to God.[8]

Thus far, this particular representation of Burāq has not been the subject of detailed analysis and interpretation. Thomas Arnold discussed the painting almost a century ago, stating simply that Burāq’s “strange caudal appendage” remains indecipherable.[9] While its meaning has remained obscure since then, the war-like angel emerging from the tip of the beast’s tail may embody the apocalyptical Angel of Death. Nearly contemporary to the Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh, the Latin translation of a now-lost Arabic-language ascension narrative, the Liber Scale Machometi (Book of Muhammad’s Ladder), records that the Prophet encountered both the Angel of Death (Malik al-Mawt/Angelus Mortis)[10] and the Guardian of Hell (Malik or Khāzin/Thesaurarius Inferni) after his prayer in Jerusalem and before his entry into the first heaven.[11] The Angel of Death informs the Prophet that God gave him the duty to separate men’s souls from their bodies, while the Guardian of Hell remains seated, holding a colossal mace in his hands with which he can destroy the earth in one blow. In the Ilkhanid painting, the inclusion of the sword and shield makes it more probable that the angel here represents the Angel of Death, ready to extract the souls of men, rather than the Guardian of Hell, whose description does not match the illustration.

The text concerned with the life of the Prophet, his mi‘rāj, and the testing of the cups in Rashīd al-Dīn’s Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh provides further information that enables a more detailed interpretation of the painting.[12] Rashīd al-Dīn’s ascension narrative is placed in the midst of conversion stories and admonition tales dealing with disbelief, thus intimating that the ascension story was used to confirm the validity of Islam and the prophecy of Muhammad. Moreover, the text describes the Prophet’s correct selection of milk upon the testing of the cups as a sign of the Muslim community’s selection and salvation by God. The reader is informed that had Muhammad chosen the wine, his followers would have been led astray. In this instance, the milk represents a gift (al-hidāya) to Muhammad and his people as well as a symbol of their embarking on the right path (al-ṣirāṭ al-mustaqīm). The Prophet’s choice of the correct cup in Rashīd al-Dīn’s narrative thus steers the believers away from evil (hell) and toward good (paradise).

While the text sheds light on the depiction of the testing of the cups in the painting, it neither explains the codex in Burāq’s hands nor the gladiatorial angel growing out of its tail. The book almost certainly epitomizes the “correct path” mentioned in the Koran’s opening chapter (al-Fātiḥa) and emphasized by Rashīd al-Dīn in his chapter on the ascension. More specifically, it probably represents one of the so-called gifts granted to the Prophet on the night of the ascension, in this case the Koran as a whole or as comprised of its individual chapters.[13] While the author’s use of the ambiguous term al-fitra (special nature or correct path) describes the positive outcome of the testing of the cups, the painting here suggests that the Koran is the quintessential conduit for moral rectitude, itself able to secure of salvation. The codex’s central position within the composition, along with the curve of the firmament and the gaze of Burāq, Muhammad, and the two angels on the right, emphasize the Holy Scripture’s central, and thus supreme, status.

Considered in tandem with the testing of the cups and Burāq’s holding of the Koran, the symbolism of the painting becomes more apparent: the Prophet straddles his winged beast, pulled between the forces of righteousness and the lure of evil. It is clear which way Muhammad will proceed, as he turns his back on chthonian might while embracing the symbols of faith and its rewards: that is, the Koran, as divine revelation, and the cup of milk, as the concrete proof of the Prophet’s decision to embark on the right path, which enables him to enter through the door to the heavens en route to paradise and God.

Powerfully moralizing, the painting reifies the promise of salvation in pictorial form at a historical moment when members of the Ilkhanid royal elite who patronized such manuscripts similarly fashioned themselves as renewers of prophetic rulership and saviors in the Islamic faith. Indeed, Ilkhanid rulers such Öljeitü (reigned 1304–16), under whose aegis the Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh was copied and illustrated, considered themselves protected by (a sky) God, the Prophet, and good fortune. Expressions of divine selection and support can be found most especially in Öljeitü’s letters, which begin with the introductory formula: “In the might of the Everlasting Sky/Heaven [= God] / In the support/belief (īmān) of the Prophet Muhammad / Under the protection of the flame of Great Fortune.”[14] The painting similarly depicts good fortune through the intermediary of the Prophet as he is about to enter the sky, the abode of heavenly beings and God.

Soaring into Heaven and Hell

The image of the ascending Prophet in the Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh forecasts the quintessential means for expressing and visualizing the eschaton via Muhammad’s flight through the heavens. Immediately after the completion of Rashīd al-Dīn’s illustrated historical text, a new genre of independent “Books of the Prophet’s Ascension” (Mi‘rājnāmas) emerged. Several books of ascension were produced as illustrated manuscripts from the 1320s to the 1460s. These manuscripts offered powerful bio-apocalyptical narratives, in which discourses on the “right path” and mercurial victory ceded way to visual exposés of heaven and hell.

In their narrative flexibility, Mi‘rājnāma texts accommodated many possibilities for textual and visual elaboration.[15] In addition, beyond narrating one of the most important miracles in the life of the Prophet, the main concern of these texts lies in describing eschatological events and realms. Much like graphic novels, Ilkhanid and Timurid books of ascension were provided with elaborate cycles of paintings, each bearing vivid imagery. The most important surviving illustrated copies are the Mi‘rājnāmas most probably made for the last Ilkhanid sultan Abū Sa‘īd (reigned 1317–35) and for the Timurid sultan Shāhrukh in circa 1436.[16] The latter includes a lavish pictorial program depicting the Prophet’s ascension through the heavens, his encounter with prophets and angels, his colloquy with God, and his visits to the heavenly and infernal realms. Fulfilling moralizing and pedagogical aims, these illustrated manuscripts depict both paradise and hell, which function as visual aids in the delineation of a belief system that promises divine reward for proper faith and behavior or chthonic punishment for a host of sins and immoral conduct.

The location, entrance, grounds, and benefits of paradise, reserved for the believers, are described in detail in the Koran. Paradise or Eden (61:12) consists in a simple garden (23:11) or a garden of delights (10:9), which is entered through gates. It is both an abode of peace (6:127, 10:25) and a beautiful place (54:55). Inside, there are gardens with rivers and fountains, plenty of shade, and fruit trees of all sorts. The righteous inhabitants of paradise eat and drink their heart’s desire from beautiful plates and vessels. Clad in lavish garments, they recline on beautiful carpets or couches inlaid with precious stones, and they know no fatigue, pain, fear, or humiliation.[17] The dwellers of paradise also are rewarded with young and pure companions, known as ḥūrīs because of their large black eyes (ḥūr ‘ayn).[18]

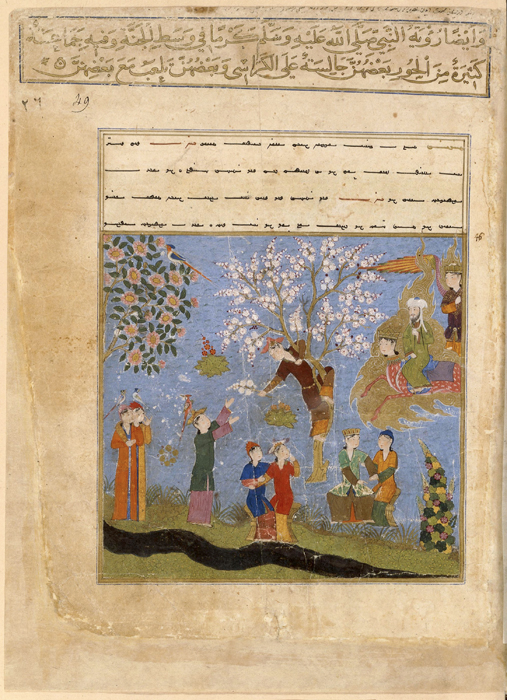

In one of the depictions of paradise in the Timurid Mi‘rājnāma (fig. 2), the Prophet Muhammad, seated atop Burāq and escorted by the angel Gabriel, witnesses a scene of carefree recreation: couples embrace lovingly on benches; others stand with birds perched on their heads; and yet another climbs a tree to pick flowers. The text records the Prophet Muhammad describing this heavenly scene in the following words: “In the garden, which God the Exalted has created for those who follow my path, are a multitude of ḥūrīs. Some were sitting on benches, while others were playing and holding hands. Birds would land onto the ḥūrīs’ heads.”[19] In Islamic sources, ḥūrīs are described as eternally young women who were directly transferred to paradise on account of their extreme piety.[20] In the Ḥadīth, ample attention is given to the ḥūrīs: we are told, for example, that they are made, wholly or partially, of saffron; that they wear seventy robes through which the dazzling whiteness of their skin is still visible; that their hair is woven into over seventy thousand braids, which must be carried by maids of honor; and that they are eternally young and wait for their future husbands to arrive in paradise.[21] As either angelic or semi-angelic beings, they are the personnel and the many embodied rewards of heaven, made fully available to the eyes of the believer through the illustrated text of the Prophet’s ascension.

As part of the Islamic eschaton, hell is likewise described in detail in the Koran, Ḥadīth, and Arabic eschatological literature. In the Koran, hell possesses seven different names, the most common of which is Jahannam.[22] It is described as an underground prison (17:8) with an infernal tree (called Zaqqūm) with demon heads for branches (37:62–68).[23] Hell also is filled with fire (3:103), which burns and dismembers the damned (70:16). The wretched are tied by the neck, hands, and feet with chains (69:30–32) and iron hooks (22:19–21). Finally, the denizens of hell wear clothes of fire, drink rotten water and molten brass, and cry for God’s help to spare them from overwhelming physical and spiritual pain.

These Koranic descriptions of hell are supplemented by the Ḥadīth and various eschatological texts. Guardian angels receive the damned at hell’s gates, after which they enter its precincts and are tortured ad aeternam. Although the Koran states that “intercession will not be any use to him except for whom the Merciful One allows it” (20:108–9), in many traditions the Prophet Muhammad acts as intercessor for his community on the Day of Judgment. At that time, he stands at the Kawthar Pond (Ḥawd Kawthar) and petitions God to release the “people of hell” (jahannamiyyūn), who are then sprinkled with water from the well of life and restored to a healthy condition.[24] From there, Muhammad further intercedes on their behalf and helps them enter paradise.[25] The result of this prophetic intercession proves that there exists the possibility of salvation after damnation for both an individual and a larger community within Islamic religious thought.

Depictions of paradise (and themes related to it) are ubiquitous in Islamic art and thus have commanded the attention of scholars for years.[26] However, the depiction of hell has not been closely examined, in no small part due to a relative scarcity of illustrations. Although it is not possible to discuss the full range of images of hell in this essay, it is nevertheless clear that images associated with damnation and the eternal fire in Islamic art served as preemptive warnings of the hereafter as well as apocalyptical caveats through which human affairs and faith systems could be regulated and implemented on Earth.

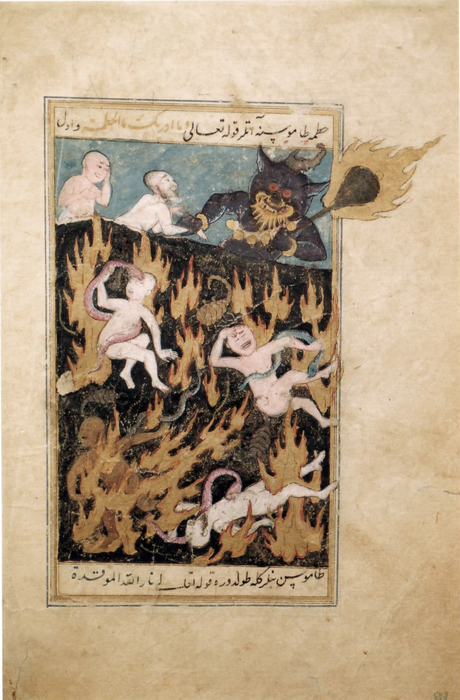

The most complete cycle of images of hell is located in the Timurid Mi‘rājnāma of circa 1436. The sixteen paintings represent Muhammad, riding Burāq and accompanied by the angel Gabriel, witnessing the various tortures inflicted upon evil-speakers, the sowers of discord, those who displayed greed, cupidity, hypocrisy, pride, and avarice; those who failed to pay alms; women who were shameless or adulterous; and those who were false witnesses or performed no good acts whatsoever. While the paintings depict eschatological punishments, they certainly were meant to enable the teaching of proper moral conduct to the manuscript’s reader-viewers, adult and juvenile alike. The use of images of hell to help implement a particular belief system and proper behavior was not restricted to the Timurid Mi‘rājnāma, however. During the sixteenth century, Safavid books of omens (fālnāmas) containing similar depictions of hell’s tortures appear to have fulfilled similar purposes, albeit under different religious, political, and cultural circumstances.[27]

One image of hell in the Timurid Mi‘rājnāma combines two scenes of torture (fig. 3). In the upper part of the depiction, a group of men with animal heads open their mouths and stick out their distended tongues. In the corresponding text of the manuscript, Muhammad is reported as saying that he saw men “with pigs’ heads as well as legs and tails similar to donkeys.” He asks Gabriel who these composite creatures are, to which the angel responds: “These are the men who, not fearing God, gave false testimony.” He then sees another group of men, killed and brought back to life while being asked one by one, “What good have you ever done?”[28] This second group of men is depicted in the lower portion of the painting: each denizen’s throat is slit over and again by red demons as they carry out God’s decree of perpetual torment for those who strayed from the right path.

The Timurid Mi‘rājnāma text blends many sources: Koranic verses describing the torments in hell, elaborate descriptions of tortures in the Ḥadīth, and information drawn from Islamic apocalyptic and eschatological works. Apocalyptic writings—such as Ibn Kathīr’s (died AH 774/1373 CE) third chapter on “The Signs of the Day of Judgment” in his al-Bidāya wa’l-Nihāya (The Beginning and End)—synthesize many sources. This process of culling and collating eschatological information finds a parallel in the visual arts of the fifteenth century. In one instance, which can be related to the painting of the torments of hell, Ibn Kathīr notes that the Prophet said that on the Day of Judgment: “Among my umma [community], some will be swallowed up by the earth, some bombarded with stones, and some transformed into animals.”[29] Alongside the calamities of engulfment (khasf) and lapidation (qadhf), the sinners’ inner degeneracy is depicted as punitive physiognomic metamorphosis (maskh), whereby the wicked transform into animals, in particular apes and swine, as a outward sign of the arrival of doomsday.[30]

Although the depictions of hell in the Timurid Mi‘rājnāma certainly reveal a reliance on Sino–Central Asian images—such as polycephalous angels and angels sitting in yogic positions[31]—they also reflect a general tendency in the development of Islamic literature at this time, when Islamic sources were synthesized to generate new eschatological narratives and paintings. In an instructive and intercessory manner, paintings of heaven and especially hell within the Timurid “Book of Ascension” use graphic symbols to elucidate the otherwise indescribable dominions of the afterlife. During the fifteenth century, it is thus principally through the Prophet’s mi‘rāj that pious readers and viewers could embark on a dramatic and instructive flight into the Islamic eschaton.

Conditions of Resurrection

After the Timurid period, eschatological imagery exited the confines of illustrated world histories and books of ascension. Interest in the conditions of resurrection no doubt increased with the approaching hijrī millennium, at which time freestanding apocalyptical works were produced as illustrated manuscripts. As the year AH 1000 drew into closer sight, paintings of the Last Judgment, heaven, and hell were included in the pictorial programs of Safavid and Ottoman fālnāmas. Although sharing in common popular religious traditions, Safavid pictorial auguries could forward a Shi‘i millenarian agenda while Ottoman manuscripts containing eschatological themes and imageries could help promote a Sunni apocalyptical worldview instead. The signs of the hour thus contributed to the greater project of constructing Sunni-Shi‘i differential identities in Persian and Turkish lands during the early modern period.

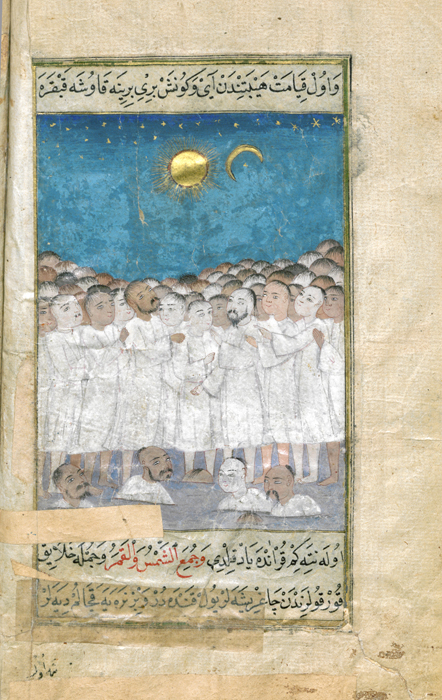

Enmeshed in sectarian contentions, as well as anticipating and envisioning the end of time, Ottoman copies of the Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma (The Conditions of Resurrection) build upon older Arabic-language apocalyptical texts while amplifying them with awe-inspiring imagery.[32] Several illustrated manuscripts of the text produced at the end of the sixteenth century are held in international collections today, in both complete and fragmentary form.[33] The many eschatological themes that they cover include, for example, the Angel Isrāfīl sounding the trumpet on the day of reckoning; the gathering of souls for judgment; inexplicable cosmic phenomena such as the conjunction of the sun, moon, and stars (fig. 4); the weighing of good and bad deeds; the arrival of the Antichrist (Dajjāl), Jesus, and the Mahdī; Muhammad’s intercession on behalf of his community; and descriptions of heavenly rewards and the punishments of hell (fig. 5). Otherworldly realms and objects—including God’s pedestal (kursī) and the standards (‘alams) carried by important individuals—are described as well.

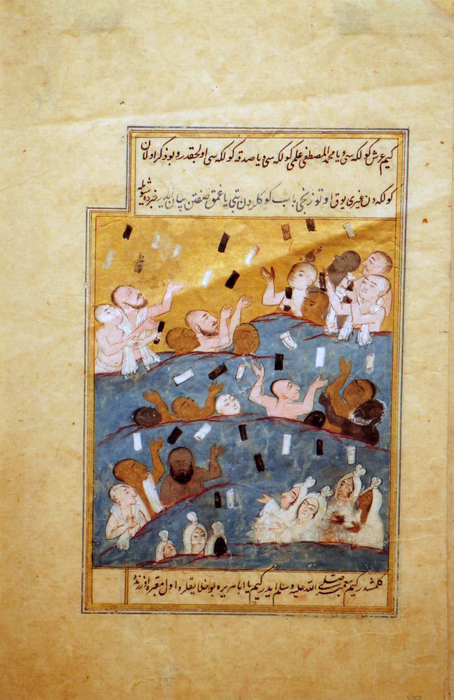

Interspersed among the many paintings included in an Ottoman copy of the Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma is one illustration depicting groups of men and women of varying skin tones, clad in white garments resembling burial shrouds (fig. 6). The figures lift their hands into the gold air as white and black slips fall from the sky. These books of deeds (kitābāt) are depicted as concrete eschatological realities (ḥaqā’iq), which determine whether those gathered for the Last Judgment will be counted among the saved in heaven (white slip) or the damned in hell (black slip).[34] The related text on the recto and verso of the painting praises the Prophet Muhammad and the inhabitants of heaven (aṣḥāb al-jinna), and provides quotations from the Koran supporting the truth and inevitability of the Day of Reckoning as it is described in God’s book (bi-kitābihi). Just as important, the narrative stresses that it is ‘Uthman who transmits the books of deeds to God.[35] In this case, the reader is instructed to imagine the apocalypse through a Sunni worldview, with ‘Uthman serving as the leading figurehead of the Sunna, as the namesake of the Ottoman dynasty, and as an apocalyptic intercessor present alongside Muhammad.

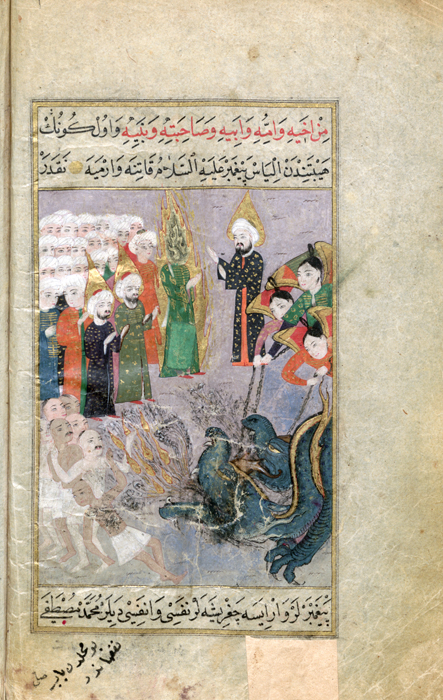

Different depictions in Ottoman illustrated copies of the Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma deliver other potentially sectarian messages, revealing the extent to which Islamic eschatological imagination intersected with Sunni and Shi‘i discourses about salvation as the millennial mark approached. For instance, another painting depicts the Prophet Muhammad, his head subsumed by a flaming gold-green aureole, accompanied by three haloed figures and a group of turbaned men as three angels hold a double-headed dragon that roars flames of fire toward several petrified souls (fig. 7). The text builds its narrative around Koranic verses that speak of the “piercing call” (al-ṣākhkha, 80:33–36), at which time individuals will be forcibly separated from their loved ones. It further mentions that the prophets, among them Abraham, Jacob, and Joseph, will accompany and nominate Muhammad as the intercessor for the community of believers on the Day of Reckoning. And finally, the text concludes with the brief statement that disbelievers (kāfirler) will not be saved from hellfire.[36]

The Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma text fails to name the three men with golden halos represented in the image, and it does not clearly identify the “disbelievers.” Despite the lack of textual specificity, it is possible to suggest that the painting offers an eschatological exegesis of a sectarian nature, by which only three of the so-called rightly guided caliphs, distinguished by their gold halos, are allowed to accompany Muhammad at the time of intercession. As a result, the fourth member of the rashīdūn—that is, ‘Ali, the figurehead of Shi‘i Islam from whom the Safavids claimed descent and thus politico-religious legitimacy—has been visually excised from the apocalyptical domain, his intercessory powers on the Day of Judgment thereby denied. With the removal of ‘Ali, the Sunni Ottoman viewer is hailed to “read” the image through a sectarian lens, itself a binary structure that invites a presumption that the damned “disbelievers” are not merely sinners but, perhaps more precisely, Shi‘i opponents of the prophetic Sunna as inherited and propagated by the Ottoman state.

Ottoman illustrated copies of the Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma provide eschatological narratives built from a mosaic work of Koranic verses in order to produce creative elaborations of otherworldly realms and events. Moreover, their paintings provide vivid pictorial “signs of the hour,” all the while visually (if not textually) asserting the ascendancy—and thus salvation—of the Sunni faith community. Going well beyond world history and the bio-apocalypse literary genres, these pictured tales strictly devoted to describing the conditions of resurrection reveal the extent to which both the impending millennium and Ottoman-Safavid rivalries generated new sectarian visions of the afterlife in the early modern Islamic world.

Charting a Cosmic Eschaton

During and after the sixteenth century, Islamic eschatological imagery developed along a new stylistic and conceptual axis, in which diagrams tend to displace traditions of figuration that typify earlier illustrated histories, biographies, and apocalypses. New conceptions of time and space as these intersected with apocalyptical realms and events were developed in books of pilgrimage to Islamic holy sites as well as gnostic-scientific cosmologies from the mid-1550s to circa 1900. From illustrated ḥajj manuals to diagrams of the Islamic cosmos, terrestrial landscapes were imagined within an overarching theological structure. As David Roxburgh has noted, these geo-theological spaces were “pregnant with meaning for they were associated with events that occur within the total frame of Muslim cosmology, some ancient, others yet to happen.”[37] Chief among these composite cosmic-terrestrial places are the two holy cities of Mecca and Jerusalem, considered the cosmic navel of the universe and the location for the Day of Judgment, respectively.

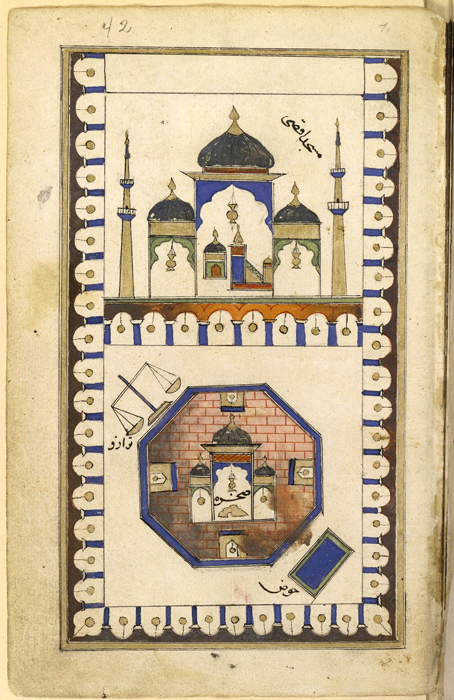

Depictions of an “eschatological Jerusalem”[38] are included in guidebooks to the holy cities, in particular Muḥyī al-Dīn Lārī’s (died 1526–27) Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn (Description of the Two Holy Cities), a Persian-language poetic text produced in numerous illustrated copies during the second half of the sixteenth century. Catering to a growing clientele, illustrated manuscripts of the Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn helped readers and pilgrims better comprehend or remember Islamic sacred sites, which benefited from generous Ottoman royal patronage at this time.[39] In these manuscripts, cities are graphically conceived and, in the case of Jerusalem, at times imagined according to an overarching eschatological framework. For instance, a number of representations of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount include the Dome of the Rock flanked by the scales of justice (tawāzīn) and Kawthar Pond, both of which are necessary for the weighing of men’s deeds and the Prophet’s intercession on the Day of Resurrection (fig. 8).[40] Other summary line drawings and paintings of Jerusalem amplify the mount’s role as the platform for the unfolding of Judgment Day by including a number of additional graphic markers and captions, such as the scales of justice (mīzān) and the bridge over hell (pul-i ṣiraṭ). Still others identify the mount as the “Rock of God” (ṣakhrat Allāh), from which it is believed that both God and Muhammad ascended into the heavens (fig. 9).[41] In such images, the depiction of real architectonic space is largely supplanted by the artist’s apparent desire to cater to the reader’s visual urge to chart and decipher the eschaton on earthly terrain.

Beyond inviting viewers to imagine themselves in both real and eschatological space—as well as navigating primordial time, present time, and post-time—other picto-diagrams of Jerusalem included in illustrated copies of the Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn reconfigure the Last Judgment city according to a sectarian worldview. For example, an eighteenth-century Indian copy of the text includes a painting of Jerusalem that appears largely based on earlier models that also include the scales of justice and the Kawthar Pond (fig. 10).[42] However, the artist has included a number of new details, such as the Tuba tree (darakht-i Ṭūbā) of paradise. In addition, underneath the cupola of the Dome of the Rock there is a circle labeled “Throne of the Lord of the [Two] Worlds” (takht-i rabb al-‘alamīn), below which a green slab-shaped symbol bears the caption “fog [or peg] of resurrection” (mīkh-i qiyāmat). Below the throne of God and resurrection platform appears the double-pointed sword of ‘Ali (dhū’l-fiqār-i ‘Alī), while the lower-right corner includes two series of three circles identified as the tongues of the truthful (zabān-i rāst-gūyān) and those of liars (zabān-i durūgh-gūyān).

This particular diagram of Jerusalem effectively combines a variety of messages: it invites the viewer to contemplate the Day of Judgment, God’s throne, and paradise all at the same time. However, access to these otherworldly domains can be achieved only through righteous behavior—such as telling the truth—and the intercession of ‘Ali, whose presence is symbolically noted through his key object-attribute, dhū’l-fiqār.[43] In sum, this topographical diagram functions essentially as a visual aid to enable a potentially pro-Shi‘i salvific vision of the otherworld through a panoply of graphic emblems and their verbal legends, themselves part and parcel of an image-based pilgrimage across the manuscript’s painted folios.

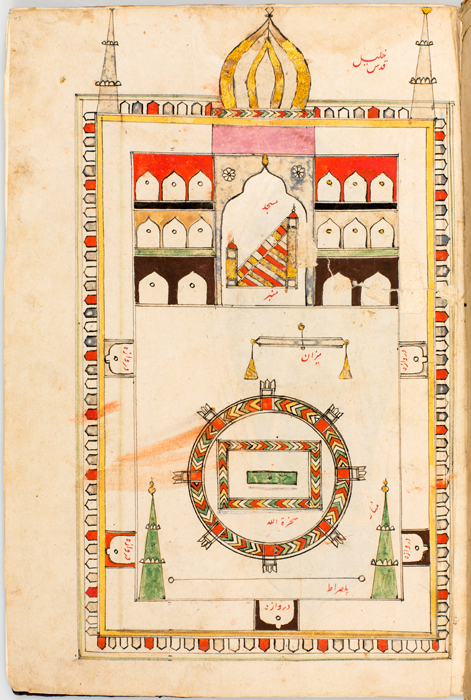

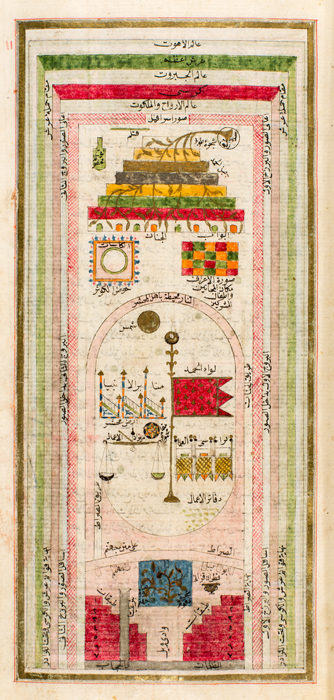

By the nineteenth century, diagrammatic visions of the eschaton synthesized numerous theological and gnostic textual sources and were integrated in late Ottoman manuscript and printed copies of Ibrahim Hakkı’s (died 1780) Ma‘rifatnāma (Book of Gnosis).[44] This ethico-mystical encyclopedia includes an introduction with sections describing God’s throne, pedestal, and pen; the celestial spheres; angels; the Day of Judgment; signs of the hour; and heaven and hell. In the introduction’s final paragraphs, the author notes that it is incumbent upon believers to meditate upon God and that the best way to understand the inner meanings and realities of the Islamic faith is by contemplating God’s signs (āyāt) and the shape (hay’at) of the world.[45] Oftentimes, a double-page cosmological diagram titled “The Shape(s) of Islam” (Hay’at al-Islām or Ashkāl al-Islām) accompanies the author’s closing words of advice (fig. 11).[46] These maps are highly detailed and packed with visual and textual information on the shape of the Islamic cosmos and conditions of the resurrection. They thus invite sustained contemplation by the manuscript’s reader-viewer.[47]

Although these esoteric-eschatological diagrams deserve in-depth scholarly research,[48] a few preliminary words can be offered here. First, the double-page images are not solely cosmic: they also represent, on the right, Mecca (with the Ka‘ba) and, on the left, Jerusalem (as the locus of resurrection). This layout recalls the facing depictions of Mecca and Medina in Ottoman illustrated copies of al-Jazūlī’s Dalā’il al-Khayrāt (Proofs of Good Deeds), but in this case Jerusalem has replaced Medina due to the Ma‘rifatnāma’s overarching soteriological narrative.[49] Second, both images include the heavenly spheres, the two celestial trees, God’s pen, and the preserved Tablet (al-lawḥ al-maḥfūẓ) in their upper sections, while the lower registers include the seven hells, the infernal Zaqqūm tree, and a pot of molten liquid below the bridge (ṣiraṭ) over hell.

The image of the Ka‘ba displays the holy site’s cosmological centrality, while the image on the left—although not identified as Jerusalem per se—represents the “land of gathering” (arḍ-i mahshar) studded with eschatological symbols typically associated with the city.[50] Among them are the scales of justice, books of deeds, the Prophet’s banner of praise (liwā’ al-ḥamd), the praised station (maqām maḥmūd), the minbars of the prophets (manābir al-anbiyā’), and a golden sun. Last but certainly not least, the chairs of religious scholars (karāsī al-‘ulamā’) are also included, a detail that both echoes and reinforces the late Ottoman Sunni theological view that the ‘ulamā’ are capable intercessors who, like Muhammad and the Abrahamic prophets, will enable members of the faith community to gain access to paradise after the Day of Judgment and the weighing of deeds. From the sword of ‘Ali to the chairs of the ‘ulamā’, these cosmic topographies offer their viewers graphic think pieces on the resurrection, itself a salvific sign that was continuously subject to sectarian contestation.

Conclusion

In Ilkhanid historical works of the fourteenth century, the signs of the hour appear closely affiliated with the Prophet Muhammad and the miraculous events of his life, in particular his heavenly ascension. As eschatological information continued to mature in a variety of Islamic textual sources of the medieval period, entire narratives about the Prophet’s ascent (Mi‘rājnāmas) proved fertile ground for the elaboration of an iconography of the celestial domains, including heaven and hell. To a certain degree, the metaphor of flight functioned as an initiatory and didactic tool to disclose the afterworld and man’s destiny.

By the sixteenth century, events beyond the grave as described in the Koran and Ḥadīth developed into the new literary genre on the conditions of resurrection, itself fueled by millenarian anticipation and sectarian debate. At the same time, illustrated pilgrimage guides helped envision the Day of Judgment on Earth, turning Jerusalem into a consecrated “land of gathering” that could be claimed by both Sunni and Shi‘i actors alike. Moreover, by the 1800s, new cosmologies were being produced to provide readers and viewers with exoteric, and at times potentially partisan, picto-diagrams with which to meditate upon the esoteric meanings of faith as well as to imagine salvation and the afterlife.

In these many depictions of the signs of the hour in Persian and Turkish book arts, the Islamic eschaton is rendered in a conceivable manner—as a set of otherworldly realities that transcend language. While some images engage in the figural mode, others embrace metaphorical expression or else explore the symbolic potential of diagrammatic forms. From pictorial images to graphic signs, eschatological imagery has had a rich and varied trajectory within Islamic book art traditions. In the end, such imagery offers a preparatory and poignant glimpse into the world of the unseen.

Author’s note: I wish to thank Evyn Kropf and the anonymous readers for their helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this article. I am especially grateful to Evyn for facilitating my research on the Islamic manuscripts held in the Special Collections at the Library of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. In the second half of the article and especially figures 9–11, I have aimed to highlight the university’s holdings of Islamic manuscripts, which are deserving of further study.

Notes

Al-Qur’an, trans. Ahmed Ali (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 524, with English translation slightly adapted.

According to Islamic religious thought, Muhammad is granted by God knowledge of the unseen (‘ilm al-ghayb), which includes details of the Last Hour. For a summary of the Koranic uses of the term ghayb, see Maurice Gaudefroy-Demombynes, “Les sens du substantif gayb dans le Coran,” Mélanges Louis Massignon, vol. 2 (Damascus: Institut français, 1956–57), 245–50.

See, inter alia, Emel Esin, “The Bakhshi in the 14th to 16th Centuries: The Masters of the Pre-Muslim Tradition of the Arts of the Book in Central Asia,” in Arts of the Book in Central Asia, 14th–17th Centuries, ed. Basil Gray (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 1979), 281–94; Esin, “Four Turkish Bakhshi Active in Iranian Lands,” in The Memorial Volume of the Vth International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology, April 11–18, 1968, vol. 2 (Tehran: Ministry of Culture and Arts, 1972), 53–73; and Thomas Lentz and Glenn Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989), 97–99.

Priscilla Soucek, “An Illustrated Manuscript of al-Biruni’s Chronology of Nations,” in The Scholar and the Saint: Studies in Commemoration of Abu’l-Rayhan al-Biruni and Jalal al-Din Rumi, ed. Peter Chelkowski (New York: Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies, New York University Press, 1975), 103–68; and Robert Hillenbrand, “Images of Muhammad in al-Biruni’s Chronology of Nations,” in Persian Painting from the Mongols to the Qajars: Studies in Honour of Basil W. Robinson, ed. Robert Hillenbrand (London and New York: I. B. Tauris in association with the Centre of Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge, 2000), 129–46.

David Talbot Rice, The Illustrations to the “World History” of Rashid al-Din (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1976); and Sheila Blair, A Compendium of Chronicles: Rashid al-Din’s Illustrated History of the World, Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (London: Nour Foundation, 1995).

On the Mongols as warring infidels and forerunners of the apocalypse, see Minhāj Sirāj Jūzjānī, Ṭabakāt-i Nāṣirī: A General History of the Muhammadan Dynasties Of Asia, including Hindustan, from A.H. 194 (810 A.D.) to A.H. 658 (1260 A.D.) and the Irruption of the Infidel Mughals into Islam, vol. 2, trans. Henry George Raverty (London: Gilbert & Rivington, 1881), 869–1296. Al-Jūzjānī repeatedly describes the Mongol conquests as a catastrophe brought on by the wrath of God and as divine punishment made manifest (p. 1124).

Color illustrations of this cycle are included in Hillenbrand, “Images of Muhammad in al-Biruni’s Chronology of Nations,” pls. 1–4, 7–11, 15, and 17–18. Also see Talbot Rice, The Illustrations to the “World History” of Rashid al-Din, figs. 29–32.

On the “testing of the cups,” see Frederick Colby, Narrating Muhammad’s Night Journey: Tracing the Development of the Ibn ‘Abbas Ascension Discourse (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008), 81–82 and 135–36.

Thomas Arnold, Painting in Islam: A Study of the Place of Pictorial Art in Muslim Culture (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928), 119 and pl. LIII.

The Angel of Death (Malik al-Mawt) appears in the Koran (32:11) and is called ‘Azrā’īl in subsequent literature. His tasks include gathering men together on the Day of Judgment and separating their souls from their bodies. For a further discussion, see John MacDonald, “The Angel of Death in Late Islamic Tradition,” Islamic Studies 3 (1964), 485–519.

Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, trans., Liber Scale Machometi/Le Livre de l’Échelle de Mahomet (Paris: Librairie Générale Française, 1991), chapters 7 (112–16) and 10 (121).

Rashīd al-Dīn, Jāmi‘ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles) (Tabriz, AH 707/1306 CE), Edinburgh University Library, Arab Ms. 20, folios 54v–55v.

On the final verses of the “Chapter of the Cow,” also known as the “seals of Baqara,” as revealed to the Prophet on the night of his ascension, see Colby, Narrating Muhammad’s Night Journey, 23–24.

Francis Cleaves, “The Mongolian Documents in the Musée de Téhéran,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 16, nos. 1–2 (June 1953), 7, 26. In Ilkhanid documents, the term for “sky” (tengri) is synonymous with God, as is evident from the term’s translation as khudā in Persian and Dio in Latin. On this subject, see Kotwicz, “Formules initiales des documents mongols aux XIII-e et XIV-e ss,” Rocznik Orjentalistyczny 10 (1934), 136.

On Islamic ascension texts, see Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, ed., Le voyage initiatique en terre d’Islam: ascensions célestes et itinéraires spirituels (Louvain: Peeters, 1996); and Christiane Gruber and Frederick Colby, eds., The Prophet’s Ascension: Cross-Cultural Encounters with the Islamic Mi‘rāj Tales (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

Christiane Gruber, The Ilkhanid Book of Ascension: A Persian-Sunni Devotional Tale (London: I. B. Tauris and British Institute for Persian Studies, 2010); Gruber, The Timurid Book of Ascension (Mi‘rajnama): A Study of Text and Image in a Pan-Asian Context (Valencia: Patrimonio Ediciones, 2008); and Marie-Rose Séguy, The Miraculous Journey of Mahomet: Miraj Nameh, BN, Paris Sup Turc 190, trans. Richard Pevear (New York: G. Braziller, 1977). For a later Timurid Mi‘rājnāma, five of whose folios are now held in the David Collection, Copenhagen, see Gruber, The Timurid Book of Ascension, 330–36; and Eleanor Sims, “The Nahj al-Faradis of Sultan Abu Sa`id ibn Sultan Muhammad ibn Miranshah: An Illustrated Timurid Ascension-Text of the ‘Interim Period’,” Journal of the David Collection 4 (2014), 88–147.

Soubhi El-Saleh, La vie future selon le Coran (Paris: J. Vrin, 1986), 15.

Abel Pavet De Courteille, trans., Mirâdj-Nâmeh, Récit de l’ascension de Mahomet au ciel composé A.H. 840 (1436/1437) (Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1975), 20.

Fritz Meier, “The Ultimate Origin and the Hereafter in Islam,” in Islam and its Cultural Divergence: Studies in Honor of Gustave E. von Grunebaum, ed. G. L. Tikku (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971), 101. The term ḥūr also was used as an epithet for beautiful women in pre-Islamic poetry; see Anthony Bevan, “The Beliefs of Early Mohammedans Respecting a Future Existence,” Journal of Theological Studies 6 (1905), 28.

Thomas O’Shaughnessy, “The Seven Names for Hell in the Qur’an,” The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 24, no. 3 (1961), 444–69.

Although its location remains unclear, hell is sometimes visualized as concentric circles or personified as a beast, such as a growling dragon; Jane Smith and Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad, The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1981), 85–94; and El-Saleh, La vie future selon le Coran, 50. Debates also surround hell’s duration: some theologians argue that it is eternal, while others state it is a temporary purgatory that will cease to exist once the damned have sufficiently suffered for their sins.

Eva Riad, “Shafa‘a dans le Coran,” Orientalia Sueccana 30 (1981), 37–62; J. W. Bowker, “Intercession in the Qur’an and the Jewish Tradition,” Journal of Semitic Studies 9, no. 1 (1966), 69–82; Louis Gardet, Dieu et la destinée de l’homme (Paris: J. Vrin, 1967), 154ff, 311ff; and Annemarie Schimmel, And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 81–104.

James Robson, trans. and ed., Mishkat al-Masabih, vol. 2 (Lahore: Ashraf, 1981), 1189 (transmitted by Bukhari).

In the past decade, there has been increasing interest in exploring the impact of paradise and the afterlife in Islamic art. In 1991–92, the Hood Museum of Art organized a traveling exhibition displaying images of paradise in Islamic art and published a catalogue with thematic essays; Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, eds., Images of Paradise in Islamic Art (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, 1991). In 1996, the Museum of Ethnology in Rotterdam held a similar exhibit, which was supplemented with a collection of essays as well; Fred Ros, ed., Dreaming of Paradise: Islamic Art from the Collection of the Museum of Ethnology, Rotterdam (Rotterdam: Museum of Ethnology, 1996). More recently, a comprehensive show held in 2001 at the Musée du Louvre in Paris exhibited Islamic art concerned with the marvelous and the strange; Marthe Bernus-Taylor and Cécile Jail, L’étrange et le merveilleux en terres d’Islam (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2001).

For images of hell in books of omens, see Massumeh Farhad with Serpil Bağcı, Falnama: The Book of Omens (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2009), 192–93, 258, 272, 292, 300.

Ibn Kathir, The Signs Before the Day of Judgement, 3rd ed. (London: Dar Al Taqwa, 1994), 32.

On metamorphic punishment on the Day of Judgment, see Uri Rubin, “Apes, Pigs, and the Islamic Identity,” Israel Oriental Studies 17 (1997), 89–105; Ilse Lichtenstadter, “And Become Ye Accursed Apes,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 14 (1991), 155–75; and Christian Lange, “‘On That Day When Faces Will be White or Black (Q3:106): Towards a Semiology of the Face in Arabo-Islamic Traditions,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 127, no. 4 (2007), 429–55.

Lentz and Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision, 97; Esin, “The Bakhshi in the 14th to 16th Centuries,” 289; and Gruber, The Timurid Book of Ascension, chap. 4.

For an Arabic-language Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma (The Conditions of Resurrection), see Maurice Wolff, ed. and trans., Muhammedanische Eschatologie (Kitāb Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma) (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1872); and for an Ottoman Turkish version by the same title, see Osman Yıldız, Ahval-i kiyamet: Orta Osmanlıca dönemine ait bir dil yadigârı (Istanbul: Şûle Yayınları, 2002). On Ottoman eschatological texts and images, see Cornell Fleischer’s studies, especially “Ancient Wisdom and New Sciences: Prophecies at the Ottoman Court in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries,” in Farhad with Bağcı, Falnama, 231–43.

See Metin And, Minyatürlerle Osmanlı-İslâm Mitologyası (Istanbul: Akbank, 1998), 240–65; and Rachel Milstein, Miniature Painting in Ottoman Baghdad (Costa Mesa: Mazda, 1990), 79 and pls. 1–2.

For a representation of the Last Judgement and resurrected souls holding their books of deeds within a Safavid book of omens, see Farhad with Bağcı, Falnama, 190–91.

Anonymous, Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma (Istanbul or Baghdad, late 16th century), Free Library, Philadelphia, T4; and Yıldız, Ahval-i kiyamet, 182.

Anonymous, Aḥwāl al-Qiyāma (Istanbul or Baghdad, late 16th century), Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Ms. Or. Oct. 1596, folios 28r–29r; and Yıldız, Ahval-i kiyamet, 172.

David Roxburgh, “Pilgrimage City,” in The City in the Islamic World, vol. 1, ed. Salma Khadra Jayyusi et al. (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2008), 767.

Rachel Milstein, “Futuh-i Haramayn, Sixteenth-Century Illustrations of the Hajj Route,” in Mamluks and Ottomans: Studies in Honour of Michael Winter, ed. David Wasserstein and Ami Ayalon (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 186–88; and Milstein, “Drawings of the Haram of Jerusalem in Ottoman Manuscripts,” in Aspects of Ottoman History, ed. Amy Singer and Amnon Cohen, Scripta Hierosolymitana 35 (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1994), 66.

On the Ottoman patronage of ḥajj routes and sacred sites, see Suraiya Farooqhi, Pilgrims and Sultans: The Hajj under the Ottomans, 1517–1683 (London and New York: St. Martin’s, 1994).

This painting is reproduced in Milstein, “Futuh-i Haramayn,” 186, fig. 13.11.

For a detailed description of this manuscript, see Evyn Kropf and Nick Krabbenhoeft’s entry for Isl. Ms. 397 available online at: http://mirlyn-classic.lib.umich.edu/F/?func=direct&doc_number=006816143&local_base=AA_PUB.

For a detailed description of this manuscript, see Evyn Kropf’s entry for Isl. Ms. 900 available online at: http://mirlyn-classic.lib.umich.edu/F/?func=direct&doc_number=006836193&local_base=AA_PUB.

Dhū’l-fiqār is not always a Shi‘i symbol, as it is also found on Ottoman objects, most especially banners. The sword first belonged to the Prophet Muhammad, and ‘Ali was also revered by Sunnis. However, within Shi‘i contexts and milieus, it can take on sectarian meaning and serve as the object stand-in of Imam ‘Ali. Such is the case for this particular manuscript of the Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn, whose pilgrimage paintings emphasize locations and shrines associated with Imam ‘Ali and Fatima.

For a study of the Ma‘rifatnāma, see Ali Akbar Ziaee, Islamic Cosmology and Astronomy: Ibrahim Hakki’s Marifetname (Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010).

Erzurumlu Ibrahim Hakkı, Mârifetnâme (Tam Metin), ed. M. Faruk Meyan (Istanbul: Bedir Yayınevi, 1999), 45–46.

For a detailed description of this manuscript, see Evyn Kropf’s entry for Isl. Ms. 397 available online at: http://mirlyn-classic.lib.umich.edu/F/?func=direct&doc_number=006822255&local_base=AA_PUB. Similar cosmic diagrams are included in other copies of the Ma‘rifatnāma held in international collections. For one well-published example, dated AH 1235/1818 CE (British Library, London Or. 12964, folios 23v–24r), see Norah Titley, Miniatures from Turkish Manuscripts: A Catalogue and Subject Index of Paintings in the British Library and British Museum (London: British Library, 1981), 48, cat. 40; Ahmet Karamustafa, “Cosmographical Diagrams,” in Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies, ed. John Harley and David Woodward, History of Cartography, vol. 2, bk. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 88, fig. 3.18; Rachel Milstein, “The Evolution of a Visual Motif: The Temple and the Kaʻba,” Israel Oriental Studies 19 (1999), 37–38, pls. 8–9; and Nerina Rustomji, The Garden and the Fire: Heaven and Hell in Islamic Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 138–40, figs. 7.5–7.6.

On the role of schematic plans, including those found in Ma‘rifatnāma manuscripts, as a means to clarify details and to amplify a theme’s imaginative force, see Muhammad Isa Waley, “Illumination and Its Function in Islamic Manuscripts,” in Scribes et manuscrits du Moyen-Orient, ed. François Déroche and Francis Richard (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1997), 110, fig. 13.

Jan Just Witkam, “The Battle of the Images: Mekka vs. Medina in the Iconography of the Manuscripts of al-Jazuli’s Dala’il al-Khayrat,” in Theoretical Approaches to the Transmission and Edition of Oriental Manuscripts, Proceedings of a Symposium held in Istanbul March 28–30, 2001, ed. Judith Pfeiffer and Manfred Kropp (Beirut and Würzburg: Orient-Institut and Ergon Verlag, 2007), 67–82.

The expression “land of gathering” (arḍ-i mahshar) can be found in a copy of the Ma‘rifatnāma dated AH 1251/1835 CE. See New York Public Library, Turk Ms. 14, folio 14r. For a brief catalogue entry of the manuscript, see Barbara Schmitz, Islamic Manuscripts in the New York Public Library (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press and New York Public Library, 1992), 272–73, cat. IV. 7; also see fig. 290 for a similar diagram in Turk Ms. 12, another copy of the Ma‘rifatnāma dated AH 1245/1829–30 CE.

Ars Orientalis Volume 44

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0044.004

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.