“King August”: August Wilson in His Time

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

For a long time, I had planned to call this essay “Me and My Shadow, August Wilson.” The title—intended to express the ironic conceit of parallel lives—had come to me out of the memory of an old Al Jolson song that must have still been around after World War II when Wilson and I were growing up as contemporaries in Pennsylvania, he in the black Hill District of Pittsburgh, and I in the white Quaker and German farmlands of Adams County. In considering it, I obviously hadn’t given much thought to the ironies of popular music back in a world where the average American’s idea of a jazz singer was an old Jewish vaudeville guy performing in blackface. August Wilson would have liked that, I believe.

I had begun writing the essay for a number of reasons, some autobiographical and some literary. On the first count, I wanted to record a rare experience of personal encounter, beginning with a September 2001 conference on writing and race at my university where August Wilson—a bare two weeks after the 9/11 hijackings—had honored his commitment to be the headline speaker, and where, as one of the organizers, I had gotten to meet him and spend substantial time with him over several days. As our acquaintance grew, we agreed to take a certain humorous pleasure in discovering how many things we seemed to have in common: we were the same age; we were both geriatric fathers, with young daughters almost exactly the same age (and we were just sappy enough to go right to the wallet photos, my Katherine, his Azula); we both grew up in late 1940s and early 1950s Pennsylvania; we were both even half German. But then there was that other matter of race. The other half of my identity was also white, but the other half of his was black; and that small fact meant that we had also grown up and spent our lives in mutually alien universes. The idea of a shared history was a crazy falsehood.

So likewise, we both knew, was any conceit of shared cultural or artistic memory. Wilson’s public lecture—the occasion proper of our meeting—elaborated his well-known vision of the unbridgeable abyss of difference, in life and art alike, separating Black America from White America. It was just that stark. And just that uncompromising. As he had done elsewhere, he asserted himself proudly, even belligerently as “a race man” in living and writing. He argued the unconditional necessity of a separatist black aesthetic and a black arts tradition, with black arts funding, black arts training, and black arts institutions. He unapologetically grounded his separatist artistic politics in the utterly bitter and alienating politics of being a person of African descent in American culture every day of his life.

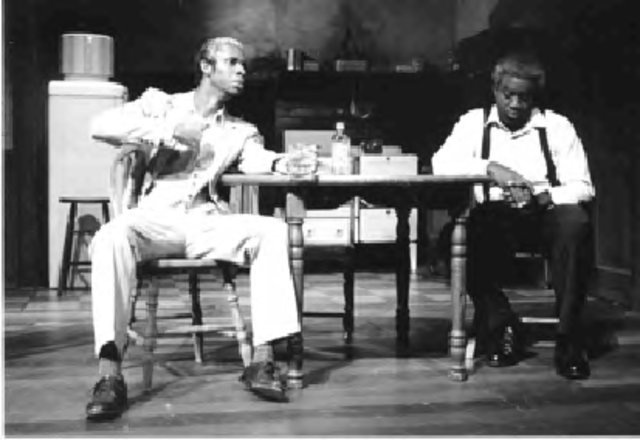

During Wilson’s visit, we had arranged performances of two of his plays. Those presented—one by our university and one by the local black college—were The Piano Lesson and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Wilson met with casts, looked in on rehearsals, and conducted student and faculty workshops. In these moments, as well as everywhere else, he honored his commitments with total generosity and attention. Near the end of his stay, I remember talking to him one last time, two hours into a hot, crowded, post-lecture reception at a faculty member’s house, where I had assured him he was not at all obliged to go in the first place. I asked him if he wanted to go back to his hotel. No, he said. He was fine. When I left him, he was in conversation with a new group of people to whom he had just been introduced. You could tell he was listening carefully to some of them who were asking him questions. When he answered, he was talking quietly, smiling.

An equally important initial motive for me in trying to write “Me and My Shadow, August Wilson,” however, lay in the transforming experience of cultural and artistic encounter I had found in the body of his work. After he left, I devoured all the print versions of the plays I could get my hands on, beginning again with The Piano Lesson and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, then everything else. I plunged into the texts, reading and re-reading, sometimes silently and sometimes aloud; marking up the pages with underlines, stars, and brackets; scribbling my own words in the margins and on separate sheets. In my mind’s eye, I tried to stage them, as Piano Lesson and Ma Rainey had been on stage; from summaries and reviews, I tried to envision the new ones coming into production—King Hedley II, Gem of the Ocean, and Radio Golf. These would complete, as was eagerly anticipated, the great August Wilson cycle of ten dramas, one for each decade, chronicling African-American experience in this nation during the twentieth century.

King Hedley II moved from the stage into print. Reviews appeared of Gem of the Ocean—set in the first decade of the now previous century. In spring and summer of last year, notices appeared for Radio Golf, the 90s play completing the cycle. Reviews covered initial performances at the Yale Repertory Theater. Further announcements were awaited concerning the tryout process in other venues whereby the play, as had most of the others, would complete its odyssey to New York.

In late summer, I saw Wilson’s photo again, accompanying a brief item in the New York Times. He was wearing, as he often did, what people sometimes called his “porter” or “newsboy” cap, but which always looked to me—given what I had seen personally of his tailoring—more like a fine English driving cap; and he also had that look he often does, quizzical, bemused, slightly startled, but meeting you right in the eye. The report concerned not his playwriting, however, but his health. August Wilson, it said, had liver cancer, with a few months to live. He was described as peaceful in spirit. “I’ve had a blessed life,” he was quoted as saying. “I’m ready.” Another, a few days later, announced that the Virginia Theater in New York would be renamed for him—the first such naming, it was pointed out, to honor an African American artist. The dedication was set for October 7. It was noted that Wilson might not live to see it.

He did not, of course. That is a shame. He would have especially liked the idea of renaming the “Virginia” theater. But he would have participated in the event mainly, I suspect, as part of being in production again, back in the city, back in the theater, wrestling with the final New York version of Radio Golf,right in the middle of the process to the end, watching, rewriting, restaging, totally reconceptualizing and reinventing, until he thought it was right. That is a shame. It is all a shame, because we are already coming to count his loss by the measure of his achievement, this American playwright who may be not simply the greatest dramatist, but also the greatest writer of our generation, and who became so by writing about the entire cultural sweep of American life in the twentieth century through a cycle of plays about black America predicated on its very incomprehensibility to white America.

So where do I—somebody from white America—get off saying these things about me and my shadow, August Wilson, who always described himself, at every opportunity, as a “race” man? Who announced at every turn what he was writing about—“black life presented on its own terms, on a grand and epic scale, in all its richness and fullness”? Who knew what kind of artistic medium he was trying to create—a black theater, centered on a black aesthetic, opening new doors to black artists, including playwrights, directors, and actors? And who knew exactly why? As he said in his famous 1996 essay, “The Ground on which I Stand,” “there is no idea that cannot be contained by black life.” Or, as he posited with an unassailable logic of both cultural and aesthetic authority—“Never is it suggested that playwrights such as Terence McNally or David Mamet are limiting themselves to white life.” Accordingly, though I make certain claims of engagement, am I thus any different from the patronizing cocktail-party acquaintance described by Wilson at an otherwise all-white gathering who proudly announced to the playwright that when looking at Wilson, “he didn’t see race”? That might be so, Wilson replied, but he didn’t notice the guy saying that to anyone else in the group.

Well Wilson was writing about race. But he also knew he was really writing about history and cultural memory, because he knew—no, he insisted—that in America the two things were one thing and could not be pulled out of each other. Likewise, in the deepest understandings of art, he knew that he was writing for the theater. And as an artist—indeed with a single-minded dedication possibly unparalleled by that of any other major figure in our time—he knew in his deepest soul that the theater belonged to everybody. Anyone who doubts either point need only read the plays.

What they will find, I am convinced, is a cycle of dramas now likely to stand as the closest thing we will have to a twentieth-century African American world picture—in the sense that criticism once talked about the Renaissance world picture; or, yes, since the term has been out there crowding Wilson for years, the Shakespearean world picture. It recalls fully the world of the tragedies, comedies, histories, and romances, an imaginative world in which it becomes possible to envision black life in America in the twentieth century through a transforming totality of theatrical experience.

At the same time, if the world created in Wilson’s plays is that of history as theater, it is uniquely history with a difference, history as predicated on the total reality for black Americans of personal and cultural difference. For what is so truly astonishing about these plays is the degree to which, even as history presides as an enormous, epochal, inescapable presence in the world of the plays, it is simultaneously a world almost totally devoid of the conventional benchmarks of official, conventional, basically white history. To put this more directly, throughout the cycle, there are virtually no current events in the traditional meaning of that phrase. The Vietnam War sneaks in as a 1969 coda to the 1957 setting of Fences. Jitney makes some reference to brands and model years of cars. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is set in a pioneering age of studio recording. There are also very few white people physically embodied. In Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, a Jewish peddler trades in piecework manufacture from black homes. In Ma Rainey we meet a music promoter. More often, white America is the landlord we never see. A rich white man, since most of the plays are set in Pittsburgh, is usually just called a Mellon. Or he is the bogey-man in a title song: the nigger-catcher Joe Turner.

Nor, it is supremely important to note from the outset, does cultural whiteness appear as in any explicit way genetic. Most specifically, racial mixing, so pronounced a theme in African American literature, goes virtually unmentioned here. Markedly absent, especially given Wilson’s own racial and cultural patrimony, is Frederick Douglass’s rage, for instance, at white fathers, or Harriet Jacobs’s at the exercise of sexual power over the enslaved black woman and mother. Just as distinctly unpronounced is the sense of double racial otherness that so permeates the sensibilities of James Baldwin or Ralph Ellison. Throughout the plays, racial mixing is simply and plainly not an issue. Blackness is the issue. Mixing or degrees of mixing do not obtain. Or rather, mixing is assumed, but so assumed that it’s not worth going into. Wilson is having no nonsense with the racial pieties of culture, academic or otherwise: “crossing,” “transgression,” “hybridity,” and the like. One drop of blood is all it takes. Black is black. White is white. This is the message of history and the experience of culture. Blood will tell. If you have black blood in you, you are black, you know it, the world knows it, and there’s hell to pay.

To be sure, the historical fact of slavery, with all its attendant horrors of blackness and whiteness, presides always in the background, along with Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the great migrations to the cities of the North and upper Midwest: New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington D.C., Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit. Pittsburgh—up the middle, in the boundary regions of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and West Virginia, a place of transit since the underground railway—becomes all of them, the chokepoint of the universe, diaspora town and promised land. It is the capital of the world. Simultaneously, it is the world of the plays, within which life itself—what happens in a family, a household, a neighborhood—frequently outstrips time or place, becoming in and of itself enormous, epochal, earth-shaking, cataclysmic.

How this works in the great cycle of the plays themselves may be at least suggested, initially, by two parallel listings, one ordered by year of appearance and the other re-ordered by year of represented chronology:

| Jitney (1982) | The Gem of the Ocean (1904) |

| Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (1984) | Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1911) |

| Fences (1987) | Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (1927) |

| Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1988) | The Piano Lesson (1937) |

| The Piano Lesson (1990) | Seven Guitars (1949) |

| Two Trains Running (1992) | Fences (1957) |

| Seven Guitars (1996) | Two Trains Running (1969) |

| King Hedley II (2001) | Jitney (1977) |

| The Gem of the Ocean (2004) | King Hedley II (1985) |

| Radio Golf (2005) | Radio Golf (1997) |

One begins by noticing certain simple, obvious things. It seems striking that the first play in represented historical chronology, The Gem of the Ocean, set in 1904, was written next to last—precisely a century later, it turns out, in 2004. The last play written in represented historical chronology, Radio Golf, set in 1997, on the other hand, turns out to have been the last in composition,written in 2005 and thereby bringing the twinned sagas of history and writing directly into the present. (Characteristically, when confronted with this idea of structural purpose, Wilson denied such a big idea by leaning back like the creator and looking at what he had created. “I went at this haphazardly,” he claimed; “. . . then I looked up one day and saw I had only the first and last plays to do. I thought it would be perfect to relate them. The two form a kind of umbrella for the rest to sit up under.”)

Certain plays oddly intersect. The titular protagonist of King Hedley II believes—incorrectly, it turns out—that he is the son of the strange, mad, oracular character named King Hedley in Seven Guitars; Hammond Wilks, the would-be communications tycoon in Radio Golf, is the grandson of Caesar Wilks in Gem of the Ocean; Fences, set in 1957, includes a 1969 coda relating to events contemporary with Two Trains Running—the very next play in represented chronology, but not in order of composition. In overall terms, as to authorial style and vision, the plays are sometimes noted as growing more mythic and less mimetic as the years of writing go on, becoming ghost dramas, the search for lost myths of history and genealogy. This may be true. On the other hand, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1988) partakes most eerily of all the early works of the sad, ghostly spirituality of Gem of the Ocean. In turn, as remarked unhappily by a number of reviewers who lamented the lack of a signature history-haunted eloquence, Radio Golf, the very last of the plays to be written (2005) and the one set closest to the present, is as unhappily barren of past reference as any day-trader hedge-fund saga.

As usefully, one notices the odd, idiosyncratic fact. As is well known, Jitney, now considered the first work in the ten-play cycle of composition, is the single one that did not make it in initial production to Broadway, presented in 1982 at the Allegheny Repertory Theater in Pittsburgh and reaching New York production at the Second Stage Theater only in 2000. It is the shadow play, albeit now appearing to us as being as concentrated, demanding, and powerful as any of the others. Was it rejected by the big time because it was too contemporary for August Wilson in the late 1970s as he was writing it and too contemporary for early 1980s audiences who would see it as distinctly contemporary? This is to ask, was it too black? To read the play now is to believe that. The world of gypsy cabs, the people who hustle to drive them, the people who call to ride in them, a representation of the world of the times, is a world on the illegal, unregulated, shadow line of free enterprise. It uses a secret, underground economy, networking through the white man’s telephones, his streets, his cars, without his approval, his franchise, his certification. It unwrites all the Public Utility Regulations of cultural visibility. (Finally reaching print in 2001, it was dedicated by Wilson to Azula, his late-life daughter.)

In a corresponding way, the literature on Wilson, scholarly and popular, abounds with anecdotes concerning his passion for the blues: how he said he had found his art while listening to an old record by Bessie Smith; how he would come sidling into a rehearsal or an interview with his latest blues discovery—softly singing and humming; how he would have to be talked out of writing it into whatever play he was trying to put into production at the time. And the music is all over the cycle: a pronounced and major element in texts as diverse as Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, The Piano Lesson, and Seven Guitars.Perhaps the play most central to the theme, however, is Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, the one play to speak directly about the experience of people who all try to make their living playing the music called the blues. Written more or less simultaneously with Jitney, it was the first of Wilson’s plays that did make it to Broadway, opening the possibility of his writing the rest of the cycleas a dramatist of major national reputation. As is well known now, it is the one play not set in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. At the same time, it anticipates the later world of the ghost plays, where a corresponding figure of woman, the legendary, oracular, Hill District matriarch Queen Ester, will frequently stand at the absolute center of everything.

From beginning to end, or from end to beginning, for that matter, it is not all that much harder to observe, in a simple way, what most of the plays are “about” in terms of basic conflict. Gem of the Ocean, for instance, brings together a group of freeborn blacks and former slaves at the house of Aunt Ester, somehow at once a living presence and 356 years old; The Piano Lesson centers on the conflict of a brother and sister over an inherited piano symbolizing their legacy of family suffering; Two Trains Running depicts the anguished attempts of a freed convict to re-enter the world through interactions with the regulars at a neighborhood café.

Wilson’s characters operate in the same dimension of direct, concrete, elemental being. They are people: as in real people, but also as in a people and/or the people. To cite Margaret Walker’s tribute to an analogous resolutely independent and uncompromising predecessor, Zora Neale Hurston, we find in Wilson the sign and index of what Walker called the possibility of “racial health—a sense of black people as complete, complex, undiminished human beings.” In Wilson, commentators have identified recurrent, signature figures. They are often middle-aged black men, angry, thwarted, hurtful, hurt-filled. They act at once cornered and disdainful, fearful of the young, the hip, the outlaw. Of the young males, as well as many of those slightly older, nearly everybody’s been in jail. Then, as has been frequently remarked, there is also Wilson’s fondness for old crazy bastards, prophets, and oracles, what Ben Brantley called “wild-eyed soothsayer types.” Concerning women, the plays likewise attest to the powerful centrality, social and sexual, of black women in the lives of black men. As characters, the women also run the gamut of age. Frequently important as figures of power, mixed with an infinite sadness of thwarted hope, are women no longer young but not yet old, a wife, a mother, or just somebody’s woman, all standing on the boundary of what the larger culture might call middle age. Here the right word would be used. Some are young icons of sexuality. Others are old, charmed, spiritually powerful—a Ma Rainey or a Queen Ester. There are not many very young children; those we see are hurt, bewildered, floating as if in a terrible dream. At the center of the cycle seems to come, perhaps, one strange, magical moment of coupling and conception—the old, mad, lonesome Hedley and the voluptuous, hypnotic Ruby in Seven Guitars. Later we find out, in King Hedley II, it has been a sexual and cosmological false alarm.

Character is thought and action in the plays—striving, impassioned, deep-hearted and deep-souled, but also frequently confused, gratuitous, and often startlingly violent. As Ben Brantley has written, “poltergeists, mad prophets, fatal curses, visions of unavenged dead men and roads to heaven” mix with “genealogies that twist into constellations of legend, and bloody crimes of passion that seem as inevitable as they are unnecessary.” But first and last, the drama of life throughout the cycle always comes down to the words. One may attempt to describe it by using the big language abstractions. Race, History, Culture, Memory: in other plays, these might be the stuff of the great speeches; in Wilson one always begins in the great word concretions, frequently as immediate and compacted as the titles of the plays themselves. Two Trains Running is about exactly what it says. One runs up north. The other runs right back south, through Memphis, back to Jackson. Once an underground railroad ran north; now one can get railroaded back south. The play is set in 1969, an age in which trains have become in great measure archaic as passenger conveyances. One takes the bus or the plane—except for a people of an invisible history of the middle of America that is itself the endless story of the old migrations, up north, and then back south, then north again, then south.

One may say the same of Fences—so simple yet explosive a titular concretion that Wilson himself came to dislike the frequency with which it was invoked in connection with his “signature” play. (Characteristically, he seems to have felt it made the play too popular. One wonders whether he also disliked the way the theme of father-son athletic genealogy and rivalry summoned a particular kind of “white,” Death of a Salesman accessibility—here, a father’s dream, for his son, of a success foreclosed to him by older racial codes.) And here, of course, the figure does begin in the commonest of common experiences. When someone builds a fence, the builder is at once fencing in and fencing out. But here the questions become immediately more concrete: whether the fence will get built or not; what happens if it does, what happens if it doesn’t. What in fact has happened to the fence project at the end? What will it have to do with being a signifier of relationships: of Troy Maxon with his younger son Cory, or of their relationships with Rose, Troy’s wife and Cory’s mother? Where will we find Lyons, Troy’s son by an earlier marriage? Gabriel, Troy’s brother? Raynell, Troy’s daughter? In 1957, the year in which the main play is set, the fence is a work in progress. In the 1969 coda, it is a falling-down ruin, a piece of instant archaeology. A fence is a thing: a fence around a house or a yard or a family, but also a city job, a prison, the loony bin at a VA hospital. Troy embodies the battle of the wall, the classic order, Priam, Hector, Paris and all the rest. Troy’s metaphors are always baseball, the dream of swinging for the fences. Lyons’s are always jazz, the old way up and out. Cory is football, the new way up and out. In the end, Fences tells the old story: no way up, no way out. At the end, we see Cory, in a marine uniform, a sergeant. He has been to Vietnam and is staying in where he has gotten ahead. He is a lifer.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is a play title by being a song title. It is thrown out, along with all the others, right up front: “Prove It on Me” . . . “Hear Me Talking to You” . . . “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” . . . “Moonshine Blues.” But it is also embodies everything about Ma Rainey: her music; her soul; her ass. It is a song about a black bottom the way something is called a black bottom pie. But it is also a song about a black bottom the way something is called a black ass. It is about getting a piece of her sweet black ass; or maybe, for the musicians, the session players, the way the system always gets a piece of everybody’s sweet black ass.

At the end, Wilson himself admitted, as he reached the final plays in the cycle, he sometimes did start getting more mystical. King Hedley II queerly fulfills certain claims of prophecy ventured in Seven Guitars. Radio Golf marks a reappearance of the richly eloquent ex-convict Sterling Johnson from Two Trains Running.Queen Ester in Gem of the Ocean is also invoked in King Hedley II, and before that in Two Trains Running. Wilson called her a “conjure woman” he always knew, as with every other character in his plays, that she stood for something more. Depending on the play, she carries the history and memory of slavery at age 287, 349, 356. In Radio Golf, Elder Joseph Barlow, a single holdout against the building schemes of the play’s slick young black entrepreneurs, now inhabits her house. Toward the end, the odd moments of the visionary in Wilson, even while remaining firmly contextual, truly did begin getting bigger and bigger, epiphanic, sometimes even cosmic.

But even as the moments got bigger, they were still made out of language in its simplest, and most direct, particular, concrete sense of human expression, of what it means to be a human person in history trying to find a sense of human community. In Wilson’s cycle, there are indeed many great speeches distributed among a vast array of characters. Language is truly eloquent, moving, furious, in precisely the sense we use when we expect drama spectacularly to comprehend a whole tradition of art, comedy, tragedy, and everything between and beyond, the whole enactment of myth and ritual into great human performance. But even here, as from the very first plays produced to the end of the magnificent cycle, it was a language of performance with a big difference—indeed the difference between Wilson’s characters and those even of Shakespeare, with whom he has been so frequently compared. Wilson’s characters in their great speeches—frequently at the seemingly strangest, most unlikely, distinctly un-epiphanic times—are just overcome by the things that come out of their mouths. To put this more simply, in Wilson’s plays, characters do not possess their speech. Their speech possesses them. They may get noble oratory, fine lines, quotable phrasings, but such speech quickly passes and blends in with all the other lines. There is no character who owns Hamlet’s soliloquy, or Charley’s rhapsody about Willy Loman riding on a smile and a shoeshine.

Language in Wilson is always made of the speaking self—experience, joy and hurt, puzzled human suffering, passion, thoughts and dreams, nightmares and imaginings, but at crucial moments it also remains beyond the speaking self in such a way as never to be contained by the speaking self. It is not too much to say that Wilson’s best speeches indeed are unspeakable, unrecordable. His actors themselves, dazzled and undone by the parts he writes for them, describe an experience of being taken out of speaking as they know it. So Charles Dutton, among the many distinguished black figures who found their legitimate theater voices in Wilson’s plays, said of his speeches: “It is a lingo that has an inherent rhythm of its own. Most of us have been black all our lives. But we kid each other about August’s writing. We’ll say, ‘I’ve never heard anything in my life like that, have you?’” Language in Wilson is an original tongue. But it is also community—“the most valuable thing you have,” Wilson was on record as saying, “in African American culture.” Sometimes it can be as simple as food: “The white man knows you just a leftover,” says Toledo in Ma Rainey. “Cause he the one that done the eating and he know what he done ate. But we don’t know that we been took and made history out of. Done went and filled the white man’s belly and now he’s full and tired and wants you to get out of the way and let him be by himself.” At other moments, as with Boy Willie in The Piano Lesson, it measures its risings and fallings by the pulse of everyday anger and confusion. “I got a heart that beats here and its beats just as loud as the next fellow’s,” he says. “Don’t care if he black or white. Sometime it beats louder. When it beats louder, then everybody can hear it. Some people get scared of that.” He goes on: “Some people get scared to hear a nigger’s heart beating. They think you ought to lay low with that heart. Make it beat quiet and go along with everything the way it is. But my mama ain’t birthed me for nothing. So what I got to do? I got to mark my passing on the road. Just like you write on a tree, ‘Boy Willie was here.’”

At still other times, as with crazy old Hedley in Seven Guitars, amidst his mutterings and rooster killings, it can even speak a vision as exalted and loony as that of the coming of the glory of the Lord. “Ain’t no grave can hold my body down,” he proclaims to no one in particular. “The black man is not a dog. You think I come when you call. I wag my tail. Look, I stirreth the nest. I am a hurricane to you, when you look at me you will see the house falling on your head. Its roof and its shutters and all the windows broken.” In all such moments, language is always somewhere within and beyond the speaker. One may talk of voicing, signification, empowerment, and still never catch the words. In the plays, the words circulate, inhabit, possess. Words get teased out of some characters; they pour out of others; sometimes they get squeezed or teased out and suddenly wind up pouring out of the same person. They are halting, searching, inarticulate; then, suddenly mad, wildly eloquent improvised, they pile out into each other, teeming and jostling; and then they rush into image and action, calling out to music, philosophy, religion, art. Wilson made a kind of mantra out of the set of influences he called the Four Bs—Blues, Baraka, Borges, Bearden. And he was right. His plays are black music; they are an embodied radical black aesthetic; they are postmodernist metafiction; they are painting and mixed-media collage. The representation of experience and thought, history and memory, in the plays is a totality of performance, endlessly seeking out the verbal and visual equivalents of nonverbal and nonvisual forms.

In this regard, as a matter of linguistic and theatrical representation, of pure performance, it is sometimes suggested of Wilson’s plays that some characters get so loaded up, they can’t carry the hoardings of vision, experience, history, and prophecy they are given. In Wilson, such work has frequently been invested in the figure of the strange, old, dirty, lonesome, crazy-talking and crazy-acting black guy. Academically, these characters have been objects of complex post-structuralist critical and theoretical understandings, frequently engrafted upon invocations of non-western myth: the shaman or trickster figure; or, specifically in the African and African American traditions, the griot or the signifying monkey. With the famous four B’s, Wilson himself supplied yet another set of figures. But then sometimes he would add Ed Bullins. As close to home were the quotations on the workroom wall: one from the white architect Frank Gehry (TAKE IT TO THE MOON); the other from the black saxophonist Charlie Parker (DON’T BE AFRAID. JUST PLAY THE MUSIC). All of this is there. But none of it really seems to be Wilson’s point about origins. That point seems to be that any person can be an oracle. Among Wilson’s characters, this is nearly always someone speaking out of some prison house: slavery, jail, sex, poverty, loneliness, abuse. Nearly everybody has been to jail, has left somebody in jail, has gotten somebody out of jail, or paid outrageous fines, bails, court costs. Life is endlessly extortionate. Men are beaten down and turned crazy by the everyday world. Women are beaten down and turned crazy by having to figure out what to do with all this, what is happening to their men, what it does to them, the future it spells for their sons and daughters. Holding households together, they sit mostly alone waiting, hoping, looking for a little love along the way; worn out, bred out, sung out, loved out. The young ones wind up having children, waiting for the fathers to shape up; watching the sons get in trouble; watching the daughters take up with and have more sons and daughters by boys and men who get in trouble. The annunciation of King Hedley by the voluptuous, fecund Ruby proclaims the conceiving of the new Messiah. Like everything else conceived of as a promise of history, it doesn’t come true here either, although we don’t find out until four plays and two decades later.

So often everything in the plays comes down not to an event or speech or even words themselves but to some collocation of language and experience barely remembered—often a song—waiting to be remembered by somebody so it can get spoken or written. And maybe paid for. In Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, there is the session-man Levee, with his frustration, his rage, and the band he dreams of for the songs he keeps getting swindled out of. In Seven Guitars, Floyd Barton is the bluesman with the dream of just one big hit. “Floyd Barton is gonna to make his record,” he tells us. “Floyd Barton is going to Chicago.”

Or it is a song that has been endlessly paid for: the great white title anthem of the blackest and oldest of all the plays, Gem of the Ocean; or, more pertinently here, the title song of the play Wilson designated his personal favorite, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone—the black song that is the title and the black title that is the song. “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” is the song that everybody tries to remember, even as it is the song that nobody ought to want to remember. It is the song of fear, of flight, of broken loves and households, of the constant nigger-catching that becomes the endless catch in the system for black Americans in the twentieth century. This one winds up being sung by a vintage Wilson crazy nigger—Landrum—to another vintage Wilson crazy nigger—Herald Loomis—now come north with his daughter Zonia, looking for the lost wife Martha, taken from him while he was imprisoned by the nigger-catcher Joe Turner. Set in 1911, nearly half a century after slavery, the drama remains the old one, of broken apart lives and families still looking for each other amidst the general dispersement. Joe Turner is the Man. Joe Turner, “brother of the governor of the great sovereign state of Tennessee,” is the man who “catch niggers.” He is the new slaver who has replaced the old enslaver, the Jim Crow, sharecropping, work-camp, lynch-law nigger-catcher. The song is the new song of the old pain. It is a song that Landrum has from memory. Now he helps Herald Loomis learn how to remember again. “Now I can look at you, Mr. Loomis,” he says, “and see you a man who done forgot his song. Forgot how to sing it. A fellow forget that and he forget who he is. Forget how he’s supposed to mark down life.” It is a song, he continues, passed down from father to son, yet also made up from the hardest sort of reaching down for “pieces and snatches” of one’s own life and memory and self. “It got so I used all of myself up in the making of that song,” he says. But that is the work required. “See, Mr. Loomis, when a man forgets his song he goes off in search of it . . . till he find out he’s got it with him all the time. That’s why I can tell you one of Joe Turner’s niggers. Cause you forgot how to sing your song.” Joe Turner’s come and gone, he says, and now come again. And he still hasn’t gotten what he wanted. “What he wanted was your song. He wanted to have that song to be his. He thought by catching you he could learn that song. Every nigger he catch he’s looking for the one he can learn that song from. Now he’s got you bound up to where you can’t sing your own song. Couldn’t sing it them seven years because you was afraid he would snatch it from under you. But you still got it. You just forgot how to sing it.”

Loomis replies: “I know who you are. You one of those bones people.” Loomis is right. Landrum sings the song to hold onto it and not give it away. For it is the song celebrating the pain and suffering of a people, their courage, their dignity, their vitality; it is a song of the undefeatability, as individual persons—a trash collector, a jazz singer, an entrepreneur, a nutcake—they wear in their bones. It is what Houston Baker, after Langston Hughes, has called the Long Black Song.

Obituary notices and memorial essays made claims for the greatness of August Wilson and his plays that hardly need my endorsement here. In academic criticism, he requires no push either, given his status as the subject of more than two hundred articles in scholarly publications and around twenty books. In his bemused way, he seemed to tolerate, even enjoy the attempts of criticism to try to appropriate him to its sundry agendas, political and aesthetic. Nor did he savor less the intermingling of artistic renown with a biographical legend predicated on his uncompromising personality in art and life alike, with the two histories of independence and resistance irreducibly interrelated—a kind of portrait of the artist finally arriving at fame and fortune by making all the wrong moves. In the age when—for all the racial curses and slights—education promised a way out of the ghetto of segregation, Wilson simply quit school when accused of plagiarizing a term paper and went out and started reading, educating himself in the tradition of the great American literary autodidacts—Benjamin Franklin, Frederick Douglass, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Samuel Clemens—into brilliant fragmentariness, sometimes complete with the divine monomania.

On the other hand, how else, one asks, could he have discovered and committed himself to a field of production totally beset, of all late twentieth-century American art forms, with notorious impossibilities: what is now called, with a completeness of admonitory implication, “legitimate” theater—a wending way through local, regional, and national arts companies, almost never reaching the celestial city, New York, let alone Broadway, and thereafter both literary and popular print? How else in turn, save through a faith in his autodidact genius, could he have compounded all those difficulties with insistence on a legendarily complex, difficult, exacting process of getting any single play, not to mention a whole ten-decade cycle, from early draft through major theater performance trial into final production? How could he have embraced the whole enterprise, as he was only too proud to announce, with a creative intelligence unsullied by any major experience or understanding of what we could call twentieth-century dramatic tradition—American, British, or Continental drama; experimental drama; the drama of the absurd; the theater of alienation; political theater; radical theater; guerrilla theater? August Wilson said once he had probably seen a total of ten plays in his life. He never went to movies.

He told the high-school teacher who accused him of plagiarism to go to hell. He told the American educational system to go to hell. He eventually told the whole American arts-funding apparatus to go to hell. He told the white American theater establishment to go to hell—and then most white American audiences along with it. He declared the independence and the freedom of his genius in the essay “The Ground on which I Stand,” the famous 1997 Town Hall debate with Robert Brustein, and in every single talk he gave to an interviewer, a critic, or a popular audience.

For all these reasons, August Wilson as an American artist of our age and of ages to come will always be too important to be left to the critics, myself included. Oriented as we are toward texts and context, we ourselves will never find the language, the terms for the magnitude of his achievement: an absolutely concentrated bravery of genius linked to an unbounded moral passion. He wrote for the stage an entire epic history of race in America in the twentieth century. And if it is largely absent of white history, it is also as frequently absent of black history in any conventional sense. Here one finds no Brown versus Kansas, Freedom Summer, “I Have a Dream” speech, or Black Power. One mainly finds individual, living, human persons, and what is left, therefore, is only everything. Everything about August Wilson’s plays bespeaks the immense vitality that went into his creations and the corresponding vitality of their effect on anyone who experiences them on stage or responds imaginatively to them in print.

No matter who you are, if you see the plays of August Wilson or read them, you will hear the song. If you hear it, you will never forget it. And you will never see history again the same way. You will simply understand, as you never understood before, that race is everything in America. You will now be unable not to remember how it presides over the slavery-haunted Declaration of Independence; how no one can or should edit out of our memory of the original Constitution the insane fiction that once certain human beings constituted three-fifths of a person. You will know that all those terrible compromises, however named—the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott Decision—were about one thing and one thing only: the shadow of race presiding over the promised land. And that every piece of American history, literature, and culture ever since—the rise of Jacksonian Democracy, the saga of the opening of the West, the Civil War, the Gilded Age, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, the Civil Rights Era, Vietnam, the Post- 9/11 Age of Terror—lives in the land of the shadow. Life in twentieth-century America has been lived, the plays of August Wilson tell us, where it has always been lived.

I think of this now any time I make up a syllabus. I think of it as I reflect on experiences and events I have personally lived through, written about, tried to discuss as an interpreter of American life and culture: the Eisenhower 50s; the Kennedy early 60s; the Vietnam War; the era of the youth counterculture. Having lived through the 70s, 80s, 90s, and into the first decade of a new century, I think of it when I make any kind of personal or cultural generalization. For me, as for so many other Americans since August Wilson came among us, what we talk about when we purport to discuss history or culture really continues to be what we don’t talk about.

August Wilson gets one entry in Bartlett’s. “As long as the colored man look to white folks to put the crown on what he say . . . as long as he looks to white folks for approval . . . then he ain’t never gonna find out who he is and what he’s about.” Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Act I). It’s the only one he needs.

Let me explain myself. When I started to write “Me and My Shadow, August Wilson,” I now confess, I already knew that I was not writing about an Al Jolson shadow but a Ralph Ellison shadow. I was not writing about a shadow but the shadow that presides over white America, the shadow that Ellison called the spook. In August Wilson, I had found a contemporary who knew what Ellison knew about white people.

I had found a shadow, as in an opening epigraph to Invisible Man, who knew what Melville knew. “You are saved,” the well-meaning American Captain Amasa Delano, with every word “more and more astonished and pained,” calls out to the titular character of Melville’s tale Benito Cereno, after he has been rescued from near-murder by mutinous slaves under the mastermind Babo; “you are saved: what has cast such a shadow upon you?” What is not written is Benito Cereno’s reply; for, as Ellison knew that Melville knew, it was the answer contained in two words: “the negro.”

Or, I had found a shadow, with his favorite white cocktail party anecdote, who knew somehow what even T. S. Eliot knew. This seemed to be the point now of the second epigraph to Invisible Man, taken not only from the most strangely white of all white writers, but from one of his strangest works—of all things, a poetic drama in blank verse actually entitled The Cocktail Party. Harry, a central speaker in the play, protests: “I tell you, it is not me you are looking at, / Not me you are grinning at, not me your confidential looks / Incriminate, but that other person, / You thought I was: let your necrophily / Feed upon that carcase. . . .”

In a personal and cultural encounter with August Wilson, I had been brought eyeball to eyeball with the shadow of my life as a post World War II–era white American. Beyond any cultural conceit, like the Nordic specimen violently described in Ellison’s first chapter, I had been bumped into by the necrophily of my unspoken history. I had been mugged by a spook singing a song that kept asking, “What did I do to get so black and blue?”

What August Wilson said he knew about white people was recorded by John Lahr in a New Yorker profile. “Blacks know the spiritual truth of white America,” Wilson said. “We are living examples of America’s hypocrisy. We know white America better than white America knows us.” He also knew the consequences for American history and memory. As phrased by his predecessor James Baldwin, “If I am not what I’ve been told I am, then it means that you’re not what I thought you were either.”

Wilson’s age in the recent announcement of his death was sixty. It was my age exactly, our age, as was fifty-six our age that day I remembered so indelibly four years earlier when he had flown in to Birmingham—Birmingham, Alabama—from Seattle, Washington. He flew first class—a stipulation made by his assistant. He was impossible to miss. He was finely dressed and immaculately mannered. A small hint of truculence—which he knew well he had in him—came with his leaning slightly forward, walking on the balls of his feet, like a boxer. I only learned some of those stories later: about the punching bag by the writing table in the basement; about the old fighter, Charley Burley, who gave Wilson his first real male image; about the nickname he got from his director, Marion McClinton: the Heavyweight Champion. I saw the temper, just once, when I said something conversational—in reference to my experience teaching judicial writing seminars—that was generally flattering to the intelligence of judges; Wilson flared, citing a newspaper article I too had read recently about a notorious Texas appellate case where a judge had declared that an indigent black defendant—given a court-appointed attorney who had spent much of the trial asleep—had been provided adequate representation. Everywhere I look now, I still feel the unrelenting insistence—in Wilson’s plays, his performance contracts, his travel requirements, and his conversation: what Richard Zoglin called in a Time article of 9 April 2005, his “principled pigheadedness.”

To the end, I now find it almost impossible not to think of Wilson, in the chair in my office where he sat in that moment as I sit here, still here, with my family, my daughter, my blessed life, my conceits about clever entitling. One more time, I think, it’s all about race. One more time, August Wilson gets the shitty deal, when he’s the genius of the age, the one who will live on as long as plays are written and performed. But I know what he would say this time, with characteristic grace, wisdom, and forbearance. Race didn’t get him. Or history. Or cultural memory. Cancer got him. Death got him. This time it was not my shadow or a shadow, as big as the shadow of race is in America. It was the shadow. But there, too, he doesn’t need a personal or literary tribute from anybody, least of all me. I am convinced he knew who he was, what he had written, and how long it was going to last. “You are our king,” Susan Lori-Parks told him in a 2005 interview. He voiced a graceful little demur, but he didn’t really object. He just said thank you. He knew that he had become King August. The one and only.