PICASSO AND HEMINGWAY: A DUD POEM AND A LIVE GRENADE

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

1.

Our perceptions are subjective, and accounts of any event are colored by the narrator’s memory and beliefs. Fascinated by our own stories and favorite jokes, we also have a keen interest in stories about the Famous and the Great. For a biographer, anecdotes are interesting not only for what happened and when, but also for who told them and why. Like popular tales that change in the telling, anecdotes about famous people alter with time. Initially the story is told by the participants themselves or by eyewitnesses; then the friends or descendants take over; finally the journalists and biographers come along to collect and reshape it. Little is known of the precise relationship between Picasso and Hemingway. They were friends in Paris at two high points of Hemingway’s life, first in the early 1920s, then in 1944. What did they think of each other, and were they really friends? Two anecdotes crop up in several versions whenever writers consider these questions.

Hemingway first met Picasso through Gertrude Stein in March 1922. He was twenty-three, just married, and getting started as writer; Picasso was eighteen years older and a famous artist. Stein had bought pictures from Picasso and helped promote his career, and she was then telling Hemingway how to write. Both men also knew the wealthy, arty, and stylish American expatriates Gerald and Sara Murphy, who lived in France and entertained lavishly. In the summer of 1925, in Antibes on the French Riviera, Hemingway spent June and Picasso July with the Murphys, who thought it safer to separate the two gigantic egos.

In A Moveable Feast, his memoir of Paris in the Twenties, written in the late 1950s and posthumously published in 1964, Hemingway, bitterly regretting some personal choices, looked back on these happy, intensely productive years and blamed the Murphys for leading him astray. He satirized them (without naming them) as “pilot fish” who led prosperous parasites to their artistic prey: “They never wasted their time nor their charm on something that was not sure. Why should they? Picasso was sure and of course had been before they had ever heard of painting.” Conscious of his present fame and wealth, and now equal as a celebrity, he co-opted Picasso in his denunciation of the rich. According to Hemingway, Picasso protected himself by pretending to accept social invitations from well-off patrons: “Much later Picasso told me that he always promised the rich to come when they asked him because it made them so happy and then something would happen and he would be unable to appear.” In fact, both Hemingway and Picasso eagerly accepted the Murphys’ generous hospitality. They were not only rich, they also loved books and art and knew how to have a good time. Biographers aren’t the only ones who rewrite history.

The young Hemingway often saw Picasso at Stein’s salon, where he learned about art and developed his connoisseur’s eye by looking at Picasso’s work and discussing it with him. In the Twenties, despite his limited means, Hemingway bought important pictures by Juan Gris, Joan Miró, Paul Klee, and André Masson. One early story about his personal relations with Picasso, in which the painter read his poetry aloud, has survived in three variants. Influenced by his friend Max Jacob, who used “the data of the unconscious: liberated words, free association of ideas, day and night dreams, hallucinations,” Picasso wrote a good deal of predictably obscure “poetry,” with private content and vague structure.

In May 1949, twenty-five years after the event, Stein’s companion, Alice Toklas, echoing Stein and patronizing Picasso, wrote a friend: “the trouble with Picasso was that he allowed himself to be flattered into believing he was a poet too. Gertrude and he had quite a scene but she told it in Everybody’s Autobiography.” In that book, published in 1937, Stein described an evening in Picasso’s flat: “We all went over to listen all evening to Pablo Picasso’s poetry. . . . The poems were in French and Spanish and first he read a French one and then a Spanish one that he turned into French and then he read on and on and then he looked at me and I drew a long breath and I said it is very interesting. . . . Pablo went on reading and he looked up and said to Thornton Wilder did you follow and Thornton said yes and might he look at it and Picasso passed it to him. Thornton said yes he was not nervous he said yes yes it is very interesting.”

In her typically repetitive and self-aggrandizing account, Stein makes it plain that it was not interesting at all. Picasso couldn’t decide which language to write in and read on far too long. It was a social occasion with a penalty attached—you had to listen to the host drone on. When he looked to Stein for approval she was politely noncommittal. Picasso naturally wondered if the Americans had understood his strange poems. The playwright Thornton Wilder cagily repeated exactly what Stein had said.

According to a story that passed from Hemingway’s first wife, Hadley, to her son Jack, the “scene” that Toklas mentioned did not take place at Picasso’s flat, but at Stein’s, when Hemingway, not Wilder, was present. Jack Hemingway described the scene to his mother’s biographers. Bernice Kert’s version appeared in print in 1983: “One evening when Picasso was at Stein’s he read some of his poetry to the hushed group, none of whom dared say anything when he was finished. There was a long silence. Hadley noticed how he was fidgeting. Still no comments from the other guests. Finally Gertrude said, ‘Pablo, go home and paint.’”

Jack told Gioia Diliberto a second version as he warmed to the story and provided a few more details. This account made Picasso “insist” on reading, supplied a motive for his poetic endeavors, and brought Hemingway into the story as a silent, neutral witness: “Hadley told her son, Jack, that one night when she and Ernest were at 27 rue de Fleurus, Picasso, who was also a guest, insisted on reading a poem he’d written. ‘Picasso thought that if he applied the same energies to poetry as he did to painting then he could be a great poet as well.’. . . After Picasso read the poem aloud, the Hemingways stared at Stein, waiting for her verdict. Finally Stein spoke. ‘Pablo,’ she said gravely, ‘go home and paint.’”

In Jack’s first version, Picasso fidgeted; in the second, the Hemingways, who probably could not grasp the meaning of the poems, stared. In both versions Picasso’s attempt at poetry is interpreted as a challenge to Stein’s status as a “great” writer, and her response is hardly tactful. The point of this violon d’Ingres anecdote was that Stein, who thought she owned those she patronized, resented Picasso’s intrusion into her territory and rather rudely put him down. Today we read Picasso’s poetry for revelation of his character, rather than its value as poetry, but Stein did not see any value in it at all. Hadley, more tactful than Stein, did not describe his undoubtedly angry reaction to her remark and the “scene” that followed. Picasso was not put off by Stein’s reaction and continued to write poetry. But it provided a valuable lesson to the young Hemingway, who wisely remained silent. In future he would learn to guard his work and not risk public humiliation by Stein.

Hemingway and Picasso at first admired Stein and then quarreled with her. In September 1951, five years after her death, Hemingway, alluding to gay painters in Stein’s circle like the Russian Pavel Tchelitchev, patronized his patron of thirty years before. As in A Moveable Feast, he asserted that Picasso shared his view. He wrote Edmund Wilson that during “her patriotic homo-sexual phase, [Stein] lost her judgement on painting completely and judged pictures by the sexual habits of those who painted them. Picasso and I used to laugh about it but we always agreed how fond we were of her no matter what she did.”

2.

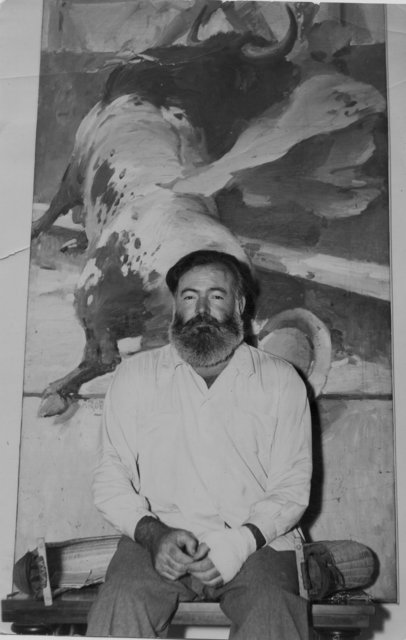

When they met twenty years later, in 1944, both men were internationally celebrated. Picasso, aged sixty-three, had been famous since Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907, Hemingway, aged forty-five, since The Sun Also Rises in 1926. The two titanic personalities were still handsome and charismatic, competitive and ambitious. The English writer Gerald Brenan recalled that “when Hemingway was in the room, it seemed that there was not sufficient air left for anyone else.” Picasso had the same capacity to dominate. Hemingway knew Spanish and shared Picasso’s passion for the bullfight. He’d reported on the Spanish Civil War from the Loyalist side and wrote his novel about the Spanish War, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), while Picasso was painting Guernica (1937) to condemn the Nazi bombing of the Basque capital.

In their private lives both were ruthless with women, whom they used up and discarded, though Hemingway had a puritanical streak that made him feel guilty. Picasso painted each of his two wives and five long-term mistresses and each one was associated with a different phase of his artistic career. Scott Fitzgerald shrewdly observed a similar pattern in Hemingway: “I have a theory that Ernest needs a new woman for each big book. . . . If there’s another big book I think we’ll find Ernest has another wife.” Most important of all, both Hemingway and Picasso created new styles of art that spawned many imitators. As Fitzgerald wrote his daughter in 1940: “You asked me whether I thought that in the Arts it was greater to originate a new form or to perfect it. The best answer is the one Picasso made rather bitterly to Gertrude Stein: ‘You do something first and then someone else comes along and does it pretty.’ ”

As a war correspondent with the American army in Normandy from June to December 1944, Hemingway participated in combat as if he were an infantry officer and then reported what he had actually experienced. Contrary to the Geneva Convention, he carried weapons, and on August 3 threw a grenade down a cellar where German troops were hiding. He deliberately exposed himself to danger and had two serious accidents. He did intelligence work, made judicial decisions about prisoners, led partisans, and conducted counterespionage missions. He entered Paris with the first Allied troops and liberated his old watering hole, the Hotel Ritz.

Just after Paris was liberated on August 25, 1944, an intensely emotional historical moment, Hemingway went to Picasso’s studio, near the Pont Neuf. There are three versions of this well-recorded visit. In the most reliable and objective account, published in 1964, Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s wartime mistress, recalled:

One of the first effects of the Liberation was the arrival of Hemingway at the Rue des Grands-Augustins. . . . [The concierge] had no idea who Hemingway was but she had been used to having many of Pablo’s friends and admirers leave gifts for him when they called in his absence. . . . When she told Hemingway that Pablo was not there and Hemingway said he’d like to leave a message for him, she asked him—so she told us later—“Wouldn’t you perhaps like to leave a gift for Monsieur?” Hemingway said he hadn’t thought about it before but perhaps it was a good idea. He went out to his jeep and brought back a case of hand grenades. He set it down inside her loge and marked it “To Picasso from Hemingway.” As soon as the concierge deciphered the other markings on the case, she ran out of the loge and refused to go back until someone took the case away.

Hemingway’s grenades were left over from the battle for Paris and he’d use more of them during the invasion of Germany. His mock offering served to emphasize the difference between Hemingway’s military and Picasso’s civilian status, and had the additional advantage of frightening the concierge, who’d cheekily suggested he leave a gift. She had an interest in soliciting gifts and hoped to share in the spoils. The grenades were obviously of no use to Picasso and no joke to the concierge, who’d just endured four years of the German occupation. Instead of bringing something useful—food, fuel, or cigarettes—the war-crazed Hemingway (who had nothing else in his jeep), gave symbolic grenades to the explosive painter who’d blown up traditional art. The joke was in bad taste, and revealed Hemingway’s tendency to hunt trophies and take risks.

Peter Viertel, the American writer and friend of Hemingway, heard the story from Picasso himself. He reported that when the bullfighter Luis Miguel Dominguín introduced him to the painter, “Picasso briefly related how Papa had come to visit him during the liberation of Paris and had offered him a hand grenade for his protection. ‘What do I want a hand grenade for?’ Picasso said he told Papa. ‘I’m a painter!’ He laughed, amused in retrospect by Hemingway’s bellicose attitude.” In this slightly embellished version, published in 1992, Hemingway, instead of leaving a case of grenades, personally hands one to Picasso “for his protection.” Picasso, commenting on the incident, is amused rather than angered by Hemingway’s bizarre behavior.

Another variant of this incident, told to a biographer by James Lord, appeared in 1988 in a hostile book on Picasso by Ariana Stassinopoulos Huffington. According to Lord, Picasso scorned Hemingway and, to free himself from his long-standing obligation to his old patron, used Hemingway as a stick to beat Stein. Speaking of the two American writers, Picasso supposedly said:

“To listen to her, the whole world would think that she created me piece by piece. But if you want to see what she really understands about painting, all you have to do is look at the trash she likes at the moment. She says the same about Hemingway. Actually, those two were made for each other. I’ve never been able to stand him, never. He never really understood bullfighting, not as a Spaniard understands it. He was a charlatan, Hemingway. I’ve always known it, but Gertrude never knew it.” . . . The torrent of abuse was still gathering force, demolishing Hemingway on the way. “He came to see me after the Liberation and he gave me a piece of an SS uniform with SS embroidered on it, and he told me that he had killed the man himself. It was a lie. Maybe he had killed plenty of wild animals, but he never killed a man. If he had killed one, he wouldn’t have needed to pass around souvenirs. He was a charlatan and that’s why Gertrude liked him.”

Luis Miguel Dominguín, angry that Hemingway had favored his rival Antonio Ordóñez in his Dangerous Summer (1959), gave Picasso the idea that Hemingway didn’t really understand bullfighting, but Picasso may have also resented Hemingway’s appropriation of his own artistic theme. In this version of Hemingway’s visit, he didn’t give Picasso grenades, but a fragment of an SS uniform, which belonged to the fanatical Nazi military elite rather than to the regular German army. Picasso could not have known if Hemingway had actually killed a German soldier (in fact, he had), and his logic about this matter (“he wouldn’t have needed to pass around souvenirs”) was weak. Even weaker was his reasoning that Stein never knew he was a charlatan but she liked him because he was a charlatan. James Lord, trying to show that he was closer to Picasso than Hemingway, recycled a half-remembered story, substituting a scrap of uniform for grenades. This anecdote, which reports Picasso attacking Hemingway and Stein, discredits Lord rather than Hemingway.

In the postwar years Picasso’s life in Nazi-occupied Paris, like Hemingway’s role in the liberation of Paris, took on a symbolic character, and both were among the most popular figures in France. Though Gilot didn’t mention it, Hemingway soon returned to Picasso’s studio and dined with him in a restaurant. In these self-conscious, semi-public, and still competitive, though disappointingly insubstantial meetings, the great complacently consorted with the great. (This is not unusual. When Joyce met Proust they found they had nothing to say to each other.) In 1976 Mary Welsh, who’d reported the incident for Time magazine and married Hemingway in 1946, wrote in her memoir: “Another evening we went to the studio of M. Picasso. . . . He welcomed Ernest with open arms and while Picasso’s girl, Françoise Gilot, a slim, dark, quiet girl with serpentine movements, and I kept ourselves behind them, Picasso showed Ernest the big, chilly studio and much of the work he’d done in the past four years. ‘Les boches left me alone,’ P.P. said. ‘They disliked my work, but they did not punish me for it.’” As they left the studio, Hemingway told Mary, who disliked Picasso’s paintings: “He’s pioneering. Don’t condemn them just because you don’t understand them. You may grow up to them.” Françoise Gilot may have omitted this return visit because she didn’t want to appear as a self-effacing nonentity, in awe of Picasso.

Soon after the visit to the studio Hemingway compromised his principles by taking Picasso to a black market restaurant in order to provide a worthy feast for his eminent friend. Mary wrote that “Picasso’s face . . . showed a dozen reactions of amusement, concern, delight at Ernest’s accounts of his adventures with the U.S. Army in France, and they reminisced rather solemnly together about the early days in Paris. . . . When Ernest asked Picasso if he would consider doing a bust of me, a portrait from the waist up, nude, Picasso’s enormous black radar eyes turned onto me, shrouded in my uniform, for a moment, smiled and said, ‘Bien sûr. Have her come to the studio.’” Hemingway then left Paris to rejoin the army and, Mary added, “without him to prod me, I kept postponing my return to Picasso’s studio. It seemed so presumptuous of me.”

Though Hemingway knew Picasso’s native language, they seemed (perhaps for Mary’s sake) to be speaking in French. Hemingway deliberately exaggerated his adventures to entertain Picasso. As he wrote of the French writer Blaise Cendrars, “when he was lying, he was more interesting than many men telling a story truly.” Mary, unfortunately, did not bother to record the rather solemn memories of their early days in Paris, which probably included some savage swipes at Stein. She was none too keen to take up Hemingway’s suggestion (it’s not clear if he’d consulted her about this beforehand) to pose half-naked in the cold studio of the notoriously lecherous Picasso, whose pictures she disliked. Hemingway admired Picasso’s latest paintings, but didn’t buy any.

Mary’s account was substantiated by letters Hemingway wrote to his son Patrick in November 1944 and to Sara Murphy in May 1945. Echoing Picasso’s “Les boches left me alone,” he wrote Patrick that the austerities of the occupation had actually stimulated the artists and that there were “lots of fine new very fine pictures by Picasso and other good painters. Under Krauts painters had nothing to do but stay home and paint. Worked out quite well. Made fine pictures.” Still infatuated with Mary and emphasizing what a great model she would be, he told Sara that lack of time (Mary’s excuse) rather than lack of interest or undue modesty on Mary’s part prevented her from posing for her portrait: “Was out a couple of times with Picasso. His stuff painted while the krauts were there is very good. Wonderful. I call Welsh my pocket Rubens and he was going to paint her but we didn’t have time. Maybe next year.”

Though Picasso never painted Mary, he did satisfy another of Hemingway’s wishes by illustrating his works. In March 1947 Hemingway wrote his editor Max Perkins that “if I can get to Europe think I might be able to get Picasso to do at least one of the books. He can illustrate beautifully you know and is a good friend of mine.” Picasso did twenty-eight black-and-white drawings for the 1959 German translation of Hemingway’s story “The Undefeated,” about an old wounded matador attempting a comeback. He also illustrated the Italian serialization, in Tempo in 1966, of Hemingway’s authoritative bullfighting book, Death in the Afternoon, which he evidently admired.

In his autobiography The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1999), the art historian John Richardson purports to give an eyewitness account of an event that took place during a corridaat Nîmes in the summer of 1959: “As the band struck up the ‘Marseillaise,’ we all stood. Suddenly Picasso laughed and pointed down at Hemingway. The author of Death in the Afternoon was standing rigidly to attention, his right hand up to his peaked cap in a military salute. When Hemingway looked around and saw that nobody else was saluting . . . he withdrew his hand and ever so slowly repositioned it in his pocket.” The point of the anecdote was to show Richardson’s intimacy with Picasso and the artist’s mockery of his absurdly naïve old friend. The incident, however, is completely out of character. Hemingway, having attended hundreds of bullfights in France and Spain while many people in the audience scrutinized his behavior, would surely know how to act when the national anthem was played. In fact, he was not even present at the corridato which Richardson refers. In The Dangerous Summer, Hemingway’s account of the bullfights of 1959, he wrote: “I love Nîmes but did not feel like leaving Madrid, where we had just arrived, to make such a long trip to see bulls with altered horns fought, so decided to stay in Madrid.”

Hemingway’s letters and Mary’s memoir suggest that he regarded Picasso as his “good friend.” Yet Picasso, according to James Lord and John Richardson, was quite hostile to Hemingway. Lord and Richardson, who made their careers by attaching themselves to great artists and writing personal books about them, had their own particular motives and wished to portray themselves as confidants of the great. They succumbed to the temptation to enliven their accounts by embroidering and even inventing stories about famous people. These distortions cluster around subjects like Hemingway and Picasso, who were legends in their lifetimes. We do not know exactly what their friendship was like, but it seems to have involved some jockeying for position. Hemingway never lost his respect for Picasso’s work. Though Picasso was cagier about his feelings, and may have found Hemingway’s boisterous arrival in Paris in the vanguard of the victorious Army a bit hard to take, he kept up professional and private relations with him. When they first knew each other, the differences in age and status would have prevented intimacy; later on, they were pleased to acknowledge each other’s celebrity.