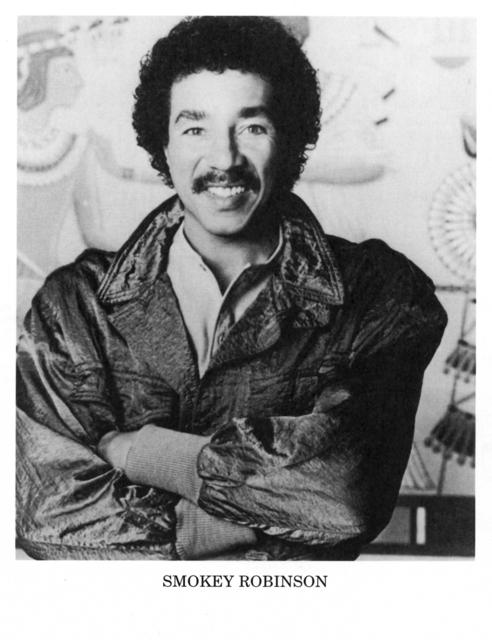

Smokey Robinson's High Tenor Voice

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

When he sang, without accompaniment, the opening lines of "You Are the Sunshine of My Life" there were those who could not restrain shouts of "Yes," shouts which seemed to inspire the singer's voice to positions on the scale that sounded beautifully impossible. When he moved into the last chorus of "The Tracks of My Tears," his whole body pulsating to the music around him, the crowd (half of them singing with him), and his own voice, one had the feeling that he was expressing a deep desperation, and his body needed to move the music to a kind of emotional, cathartic conclusion. When he sang, as if it were a spiritual, the opening stanza and chorus of "Bad Girl," his first recorded song from seventeen years earlier, changing it to the slow adolescent 1960 song "You Can Depend on Me," there were claps and appreciative remarks, almost personal, from those who knew the words and melody by heart. One woman stood up, and began applauding as loud as she could. The music, in its totality, had a way of taking hold of every sense. The intermingling of instrument and vocal in a coherent, harmonious rhythm went directly to that point in the human body where all the blood flows through.

And, it seemed, when he had finished his last song, "Happy," the theme from Lady Sings the Blues, a song for which he applied lyrics to the melody of Michel Legrand, the crowd sat as if it were stunned, as if all the music of the previous hour had not yet assimilated itself into their nervous systems, as if the music they had heard had become an inexorable part of the air surrounding them. They wanted, it seemed, to take it all away with them, so that they could, when they wanted, remember again something they had remembered for the first time as they listened to Smokey Robinson's high tenor voice weave itself like a musical instrument through the dark, thick June air opening with stars, between jazz-like piano melodies, the sound of an electronic harp, the saxophone, its sound coming up from the bottom of someone's self, the gentle, soft, almost rolling rhythm guitar of Marvin Tarplin, and the passionate, gospel voices of Carmen Twilly and Joyce Bradford, who half-sat on stools throughout the whole performance, giving their voices, through microphones, to the night.

(journal entry, Detroit, June 1975)