The impact of religious difference and unemployment/underemployment on Somali former refugee settlement in Australia

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Australia has resettled many Somalis as part of its annual refugee intake; upon coming to their new host country, Somali communities face multiple challenges with regards to successful settlement. The majority of Somalis are Muslim and are visibly different from the predominantly Anglo-Australian population. This paper presents findings from a small-group qualitative study in Australia that explored the challenges Somalis face in the employment context, and the resulting impact of unemployment/underemployment on members of the Somali community. It reports narratives gathered from 16 Somali males and females (employed and unemployed) via focus groups in Brisbane, Australia. These narratives painted a picture of perceived discrimination and marginalization due to religious affiliation, which led to unemployment/underemployment within the community.

Keywords: Islamophobia, Somali refugees, employment, Australia, visible difference, discrimination

Does religious difference disadvantage Somali former refugees in terms of employment in Australia?

In recent years, continual bloodshed, extreme poverty, and drought in Somalia, have resulted in an exodus of Somalis into refugee camps in neighboring countries followed by humanitarian resettlement in other countries. In 2009, there were an estimated 18,560 Somali asylum seekers resettled as part of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees’ resettlement effort (UNHCR, 2009). As a signatory to the 1967 UN protocol on the status of refugees, Australia is one such example of Somali resettlement. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ [ABS] census established the Somali-born population of Australia at 4,316 people[1] (ABS, 2007), which in the two years before July 2008, was augmented by 197 Humanitarian and Refugee visa entrants (Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 2009).

Within Australia, the size of Somali communities across the states and territories of Australia greatly varies. Though the Victorian population accounts for more than half of all Somali-born residents (ABS, 2007),[2] Queensland has been the most consistent state in any major intake of Somali humanitarian and refugee entrants. Indeed, between 1998-2008, while there was a 77% decrease[3] in Somali arrivals at the national level, there was only a 44% decrease[4] in Queensland (Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 2008). The city of Brisbane (in the State of Queensland) continues to account for the majority of Somali residents, with the southeast outer corner of the city becoming home to 43%[5] of the 232 Somalis living there (ABS, 2007).[6] Local Somali community leaders, however, emphasize the need to treat census data with caution because of inaccurate recording and the nature of refugee migration.[7] Anecdotal evidence places the number of Somalis in Queensland closer to 5000.

Given that the vast majority of Somalis are Muslim (Middle East Policy Council, 2002), shared religious identity is a powerful unifying factor within specific resettled Somali communities (Sadouni, 2009). In the past few years, however, the Somali community, and the Muslim community in general, within Australia has been drawn into a fierce debate about immigration and African Australian minority groups. Indeed, a failed domestic terrorism attempt[8] positioned Somalis in a negative light in the Australian media and the broader society, because of the group of men involved and their alleged connection to the Somali terrorist group al-Shabaab (Rout, 2009). The Special Broadcasting Services’s (SBS) social forum program, Insight, covered this event in a live national broadcast, and spoke with members of the Australian Somali community (Worthington, 2009). The forum revealed some alarming concerns about Somali Australians’ feelings of isolation, discrimination, and confusion, stemming from the public reaction, and the symbolic importance of the event for Somali Australians living in this country. The last few years have also witnessed increasing debates about the burqa ban, not only in Europe, but also in Australia. Since 9/11, the hijab and burqa have been associated with security risks and terrorism, and have attracted symbolic meanings of oppression and threat for the women that wear them (Hebbani & Wills, 2012; Droogsma, 2007; Kabir, 2006; Navarro, 2010; Ruby, 2006; Mishra, 2007). Such representations of Islam and Muslims in the multicultural West, is an example of ‘othering’ within the media (Hebbani & Wills, 2012; Hopkins, 2009).

The Somali community has been the focus of research in Australia (see Correa-Velez & Onsando, 2009; Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2003; Hebbani & Colic-Peisker, 2012; Tilbury & Colic-Peisker, 2006). Recognizing that gaining employment is a critical precursor to successful long-term settlement (see Ager & Strang, 2008), other researchers have also documented the impact that unemployment and underemployment has on former refugees in terms of their mental health with many experiencing depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anger, and frustration (see Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2007; Gorman, Brough, & Ramirez, 2003; McMichael & Manderson, 2004).

But given the particularities of Somali Muslim identity in Australia, negatively portrayed in Australian media, a more religion-focused study of this community and their issues with integration into Australian society is warranted as, a) many Muslim refugees resettled in Australia are often subjected to Islamophobia (see Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2007), b) many Somali women are visibly identifiable as Muslim through their dress (Akou, 2004), c) many Somali men are identifiable as Muslim through their facial hair and sometimes dress, and d) for Somali men and women, their names also reveal their Muslim identity. Hence, the focus of this paper is to report findings from a qualitative study which examined the impact of religion and visible difference on Somali former refugees in the employment context, and the resulting stressors.[9]

Cultural Differences

Before commencing research, it is crucial to understand the context in which the study is located. In this case, it is vital to appreciate the cultural differences between Somali and Australian culture. Being cognizant that language proficiency impacts refugee employment, it is important to discuss linguistic differences between Somalis and the wider Australian community. Most Somalis are Muslim and speak Arabic and Somali, and some educated Somalis arrive already speaking English; in Australia, a majority of the local population speaks English, which is the national language. A practical disadvantage for refugees is the adaptational demand of daily communication and integration (Ager & Strang, 2008; Hebbani & Colic-Peisker, 2012). However, the severity of this disadvantage in the Somali community should be understood from a historical and linguistic perspective, which emphasizes the disruptions to schooling from civil war and migration, the wide spread illiteracy in adults and the fact that the Somali language was only first formally documented in 1972 (Yusuf, 2005). From the outset, Somali communication, as a result of resettlement, is severely restricted by the lack of a basic skill set in reading and writing. Thus, a range of research (Jelle, Guerin, & Dyer 2006; Koshen, 2007; Nilsson, Brown, Russell, & Khamphakdy-Brown, 2008; Yusuf, 2005) suggests that acculturation in Australia elicits intrapersonal and intercultural conflict for Somalis based on the transfer of societal pillars in a Western culture.

Another crucial part of contextualizing the Somali experience is to consider the role of women in resettled families and in the stratification of refugees in host societies. Somali women have adapted rapidly to the demands of their role as single-parent breadwinners (Koshen, 2007) or as working wives and mothers (Jelle et al., 2006). Indeed, these women in particular have been the focus of research about job attainment and maintenance while attending to large families (Jelle et al., 2006). An ability to negotiate religious freedom and preserve certain practices like the use of the hijab (head scarf) has also been documented (Jelle et al., 2006).

Visible Difference

The religious differential between Somalis living in Australia and the host country population is important because discrimination based upon visible difference, “...may be compounded for black African Muslims” (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2007, p. 3). This study applies Colic-Peisker’s (2009) theoretical concept of “visible difference,” which refers to:

...the ethnic characteristics that make immigrants distinct in the Australian (western, English-speaking) social context and among a predominantly white population. This can be based on race (skin color, physical and facial features), or accent and publicly observable cultural differences, such as attire (often to do with religion, e.g., Muslim hijab). (p. 176)[10]

This paper applies visible difference to examine the challenges faced by Somali former refugees on employment. The relevance of visibility in terms of settlement is that it often marks out refugees (as well as other visible migrants) for differential and sometimes discriminatory treatment in the workforce and other societal domains of their host countries (Colic-Peisker, 2009). Colic-Peisker and Tilbury’s (2007) investigation into the effect of visible difference on employment found that African minority groups (from Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea) suffered high levels of unemployment based on race, religion, and ethnic origin, with multiple narratives reflecting racial discrimination in the workforce. Other Australian studies have also found that unemployment and underemployment is a problem among Muslims in Australia as a whole (Constable, Wagner, Childs, & Natoli, 2004; Guerin, Guerin, Diirye, & Abdi, 2005; Poynting & Mason, 2007; Tilbury, 2007). The next section provides an overview of Somali visible difference due to external religious markers.

Religious Markers

Somalis are noticeable by their skin color, tall and slender physique, and narrow facial features in Australia’s predominantly Anglo social population. Somali women in the West have been known to wear hijab, variations of the jilbab (i.e., long-sleeve, ankle-length garment worn by some Muslim women), and colorful Somali creations like the garbasaar or a Western style of religious dress with its smaller head piece, the masar (Akou, 2004); Somali men tend to wear conservative Western dress and are sometimes religiously identifiable because of the use of a type of hat called the kufi (Akou, 2004). In short, Somali men and women are distinctly visible as African Muslims, and are thus vulnernable to marginalization according to discriminatory trends relating to skin color and religion (see Valentine & Sporton, 2009).

For mainstream Australians, the perceptions of Islam in the West post 9/11, and post-2002 Bali bombings, may have impacted the significance of highly visible religious markers because of associations made about extremism and a fear of Islam (see Poynting & Mason, 2007). Somali women are also similarly interpreted through the visible marker of religious dress, which negatively exposes Somali women to Western interpretation of Muslim identity and prescribed gender values (Jelle et al., 2006). In fact, Dunn, Klocker, and Salabay (2007) conducted a survey among Australians and found that 41% of respondents viewed Islam as posing a minor threat to Australia, 15% perceived Islam to be a major threat, and 66% thought that Islam posed a threat of some level but were unable to exactly articulate the form of threat. Hence, they concluded that there is a strong sense of unsupported and unsubstantiated fear and apprehension of Islam among Australians (i.e., Islamophobia).

Somali Employment Outcomes

A number of successful resettlement narratives have explored Somalis’ innovation and skill in the workforce and in micro-enterprise (Campbell, 2006; Guerin et al., 2005; Jelle et al., 2006; Koshen, 2007; Sadouni, 2009). Somali refugees are claimed to adopt a range of skills once outside Somalia, suggesting that migratory experiences enrich their recourses for stability during resettlement (Sadouni, 2009). In the New Zealand and South African contexts, research has suggested that bilingualism [languages other than English] is a highly transferrable skill that should work to the advantage of Somali settlers. For instance, in New Zealand, approximately half of all Somalis spoke more than one foreign language, which Jelle , Guerin, and Dyer (2006) suggested had relevance in a country with chronic refugee unemployment and an employee market that lacked bilinguals. Meanwhile, in South Africa, Sadouni (2009) claimed that a large group of legally recognized Somali refugees in Johannesburg were able to obtain employment as interviewers for refugee applicants and as translators for the Department of Home Affairs.

In spite of the apparent need to harness the strengths of this community during resettlement, the reality of host nations such as Australia presents certain structural, social, and economic disadvantages to resettled Somalis. UNDP data suggest that 44% of international Somali migrants have less than upper secondary training and that on average 28% of both sexes are unemployed in their destination country (UNDP, 2009). Hence, recent studies have investigated the cause-and-effect nature of resettlement success in New Zealand and Australia based on employment outcomes and these are briefly presented below.

Jelle and colleagues’ New Zealand study (2006) documented the experiences of six Somali women in finding and maintaining paid employment, all of whom participated in some level of paid work, and expressed an overall satisfaction with the job market. However, the satisfaction was the result of a long-term approach that included improving and upgrading skills and qualifications, negotiating with employers for religious freedom, balancing family commitments, and the subtle transfer of skills gained in Somalia. However, in the Guerin and colleagues’ study (2005), where 83% of participants were unemployed, the 55 Somali women and 35 Somali men expressed a range of similar concerns including discrimination due to age, skin color, and formally recognized qualifications, while women in particular (22 in total) specified discrimination relating to religious dress.

In an Australian study, Yusuf (2005) juxtaposed the aspirations, barriers, and achievements of Somali students in Melbourne with the social conditioning of Somali families. In this study, 24 students (female and male) and 24 parents (mothers and fathers) shared their observations about the education system and the academic performance and aspirations of their children. He found that parents tended to prefer jobs in medicine, teaching, engineering, and mechanics, and were resistant to professions in the arts, and in the military and police. Meanwhile, students spoke of the importance of money over study and of the better academic outcomes of female Somalis. They reported major difficulties, such as a lack of understanding of western education and employment systems, insufficient skills to plan ahead (as many still lived in “survival mode”), a lack of positive role models, and an academic disadvantage. However, as the Somali community in Australia grows, it provides an opportunity to analyze the implications of unique social, communicative, and religious issues on their overall settlement.

Methods

The purpose of this qualitative study was to gather narratives from the Somali community living in the Greater Brisbane region on their experiences with finding employment. It is important to note that this study was not specifically designed to investigate the role of religion or visible difference on employment or on their mental health, but, rather, the findings presented in this paper emerged through the participants’ narratives when one of the questions asked whether they faced any cultural issues when looking for work and the resulting impact on their lives.

A local refugee employment service provider contacted the local Somali Community Association to solicit participants for this study. Through this process, in early 2010, four focus groups were conducted with a total of 16 participants (3 employed females, 3 employed males, 6 unemployed females, and 4 unemployed males). The conversational/participatory nature of a focus group was more likely to generate topics for discussion that were of concern to the participants; thus, the data collection was more of a conversation prompted by open-ended questions.

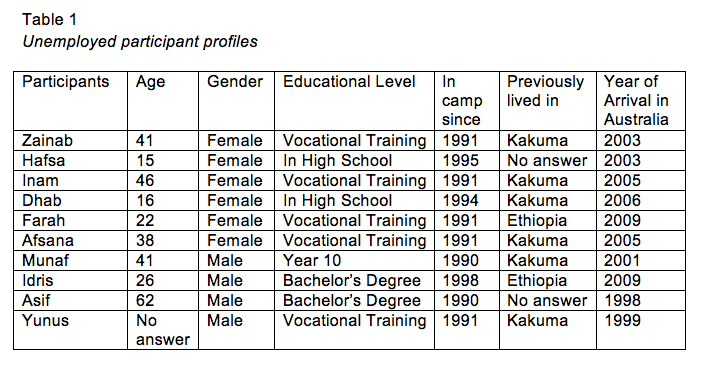

The focus groups were also segregated by gender and employment status. Table 1 presents the profiles of unemployed participants, and Table 2 presents the profiles of employed participants.

All participants identified themselves as Muslim and indicated that they spoke Somali Arabic at home. A Somali female bilingual community leader assisted with interpretation when needed for the female focus groups, while the male leader of the Somali community assisted with interpretation with the male focus groups. However, it must be noted that both the employed and unemployed male focus groups did not require much interpretation assistance, as the men were much more proficient in English as compared to the women. Specifically, the unemployed female focus group required the most interpretation assistance due to the lowest levels of English proficiency among the majority of the participants.

The male and female employed focus groups lasted longer than the male and female unemployed groups.[11] All focus groups were recorded for transcription purposes and the audio files were deleted after transcription. The transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 8 for analysis. To ensure anonymity, all participants were assigned pseudonyms; they were not remunerated for their involvement in this project.

Findings

To aid comprehension, the first section reports findings from the male employed and unemployed focus groups, and the second section reports findings from the female employed and unemployed focus groups.

Themes from Somali Male Focus Groups

In line with previous research (see Colic-Peisker, 2009; Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006), participants felt disadvantaged in the employment market for a multitude of reasons, such as educational qualifications not being recognized, lack of local work experience, no local references, no copies of certificates, and differences in job-seeking practices (e.g., having to write a resume and addressing selection criteria). According to Asif (62, unemployed), within the local Somali community, up to 80% of young Somalis (20- 40 age group) were cab drivers, not out of choice, but out of necessity. All male participants were educated; some participants even had Associate’s and Bachelor’s degrees. Many had obtained vocational certificates in a range of occupations (e.g., meat packing, childcare, aged care, community welfare, hospitality); however, most of the men in both focus groups, regardless of their educational qualifications, were still either unemployed or resorted to driving taxis in the face of unemployment.

Impact of un/underemployment. Munaf (41, unemployed), Yunus (unemployed) and Asif (62, unemployed) narrated how Underemployment and/or unemployment led to men experiencing severe financial difficulties (e.g., being unable to pay bills and needing to not only support their family here but also back in Somalia). Mohsin (employed), Aslam (38, unemployed) and Habib (52, employed) mentioned that financial issues caused not only considerable mental stress and frustration for employed and unemployed participants, but it also affected their self-esteem in their role as head of the family and primary breadwinners. This, in turn, resulted in high levels of dissatisfaction with their life in Australia.

Perceptions of covert discrimination. The men, whether employed or unemployed, reported sensing underlying currents of discrimination in Australia. It was hard to prove; as Munaf put it, “You can smell it [discrimination against Muslims] - you can sense it.” Habib blamed terrorism incidents in Somalia and the resulting negative coverage in the media for discrimination against Somalis in Australia. In their perspective, discrimination was the root cause of their employment woes as a result of (a) being Muslim, coupled with (b) the negative coverage of Somalia in Australian media (civil war, pirates, refugees, and terrorism).

Stories of being rejected for jobs were plenty, but there were also a few men who felt that in the past few years, their being Muslim was the primary reason for not getting jobs they were qualified for. To overcome this hurdle, Munaf resorted to leaving his Muslim first name out of the resume and would get an interview. But during the interview, it would be obvious that he was a Muslim applicant, and he perceived this as influencing the hiring decision and he did not get the job. While being rejected for a position could be attributed to many factors that can truly be understood only after talking also with the employer, Mohsin talked of how Australian employers responded when learning that the applicant was Muslim, “Oh, they’re not going to tell you, ‘We don’t like you because you came from this country’ so they say ‘Oh, we are not hiring at this time,’ or ‘We’ll call you back,’ but they never do,”; such responses were starting to disenchant him. Similarly, Habib too felt that his religion was a factor that impacted on employment, “Last three years or so religion has been an issue. Before that it was more colour than religion...”

The participants were all cognizant that no employer would explicitly state that they discriminated against Muslims, but an overwhelming majority of participants had experienced such discrimination. Another example of perceived discrimination due to visible difference (albeit not employment-related), Munaf felt that he was being discriminated against by the police for being [black] African, and being pulled over by the police for no apparent reason (i.e., when he was not speeding and was following all the road rules).

To work or study - that is the dilemma. Many of the men reported being caught in a cycle wherein they had to earn quick money to support their families, and so did not have time to further their education or develop higher-level skills, but on the other hand, without further education, they could not get a job that would pay them well. Habib, before his arrival in Australia, had high hopes of earning a substantial income and easily getting a job. He describes their reality being in stark contrast to their expectations:

When the people are coming here [Australia], they come with a lot of hopes, especially us who came first. There were no people to give us information and there was no structure or orientation for you coming here. So there were moments when people you knew when you got accepted to come to Australia said, ‘You’re going to Australia? Woah.’ As soon as you learn you get $10,000 worth of money per child and you get everything. You think everything is easy - you [can] get an easy job and all these things. So you come here with very high expectations, which is not the truth.

Cultural clash. The employed Somali men also attributed their difficulty in socializing with Australians to the religious and cultural difference between Somalis and Australians. Since most small talk at work with Australian colleagues revolved around drinking alcohol (some Somalis due to religious reasons do not consume alcohol), swimming, or partying, most felt left out of conversations with their workmates. Habib talked of how such differences resulted in him feeling isolated and how it affected interpersonal relationships with workmates. In addition, Munaf gave an example of how his friend was devastated as he was fired for praying during his break time, and as is generally not in Somali culture to know their rights and ask for explanations, the man did not argue.

Overall, the men largely blamed the Australian media for their undesirable experiences. As Habib stated, “As long as the media doesn’t say anything bad about you, yeah, they [Australians] are good. Once that little box says something, you can feel it straightaway, within 24 hours. The media can make or break the experiences of migrants.” Munaf explained that once Australians watched such negative portrayals, their minds would be made up that “Somalis are like that, and in the next stage, they would apply it to the Somalis they meet.”

All in all, the Somali men reported feeling stressed, depressed, and having low self-worth, in addition to perceptions of being discriminated against, and facing quadruple marginalization for being a) Muslim, b) Somali, c) refugee, and c) black.

Themes from Female Focus Groups

While all the female Somali participants were either in high school, high-school educated, or had vocational certificates in a range of occupations (parenting, childcare, hair dressing, and community welfare), not a single female participant had a university degree. None of the unemployed women had any work experience in Australia.

Implications of religious dress on employment. The unemployed women perceived their English proficiency to be poor, having arrived in Australia within the past 7 years. By comparison, the three employed women had multiple vocational certificates and perceived their English proficiency to be excellent, and had lived in Australia between for 1 and 10 years. The difference in English proficiency was apparent during the focus groups, as the employed Somali women spoke English fairly well as compared to the unemployed Somali women. The participants spoke of the interrelated nature of English proficiency and their religious dress on their employment outcomes. Specifically, two unemployed women elaborated on their experiencing discrimination and unfair treatment due to religious dress. Both women wore hijab and jilbab, which they described as a part of their cultural identity. In fact, Inam (46, unemployed), who came to Australia in 2005, vehemently put the point across that she would not change her dress (i.e., stop wearing the jilbab) to get employment. On the other hand, Dhab (16, unemployed) who used to work at a fast-food counter, quit her job just two weeks before the focus group, the reason being her boss who, “…doesn’t like how I dress. Every time he says, ‘Don’t wear the scarf [hijab]’ and things like that…” The employed women attributed the inability to get jobs to lack of English proficiency and dress, as Zubeida (23, employed) said, “So basically it [employment due to low English proficiency] makes it very difficult, because they don’t understand me, and [also] they see me – I’m wearing a big coat and a scarf and I look kind of scary. You [they] won’t give me a job.” Touching on the implications of religious dress on visible difference, Wahida (employed) also attributed the high rates of unemployment within the Somali female community primarily to dress with English proficiency playing a secondary role:

Even if your English is so good, the problem is that we can’t overtake [change] the way we dress because they [Australians] all the time focus on how we dress. Australia is a multicultural country and it is still hard because they need to understand that religion of respect – how [why] the person is wearing those clothes.

Zubeida was even more direct in talking about how religious dress isolated the women more than the Somali men:

It doesn’t matter about [language or age]. You see this burqa, but you have the qualifications, the certificates, all the skills, you have a car, but because of your clothes [you don’t get a job]. We are a target because of our clothes. It’s not about the skin color or the place. It doesn’t really matter where you’re from. The reason that you’re isolated a little bit is because you’re wearing the scarf, they [non-Muslims] don’t. You’re Muslim and they’re not.

Why were the Somali women easier to identify as Muslims than Somali men? Once again, Zubeida pointed out that the women were visible as Muslim, due to their dress as compared to the men, “When you see me on the streets, you can see I’m Muslim. With the men, you have to ask them.” The three employed women reported feeling isolated at work, and Zubeida said, “I feel that I’m not included in my workmates, what people do and the people I work with, because I’m wearing the scarf and I’m Muslim. It doesn’t matter if I’m black or from Africa or Asia or where they come from. It does matter if I’m wearing the scarf.” But the Islamic dress was part of Zubeida’s identity:

If I didn’t want this scarf, I wouldn’t wear it, you know? If I don’t want to wear a long skirt, I wouldn’t wear it. But, it is part of who I am as a Somali, black, Muslim girl, and I wear that.

Thus, through these narratives, it is evident that for the female Somali participants in this study, wearing the hijab and/or jilbab was a core element of their cultural and religious identity, and whether to wear or not wear their religious dress, was never in question. Thus, not wearing the hijab/jilbab in order to gain employment was never an option, even though they felt at times isolated from the mainstream Australian population as a result of their dress choice.

Islamophobia in Australian media - implications. Interestingly, just like the male participants in this study, the women attributed such experiences and treatment from others to ignorance among the wider Australian community about Islam and misinformation about Islam in Australian media. All three employed women said that proper education about Islam and Muslims was needed to erase ignorance and correct misperceptions within the non-Muslim population. Farida (21, employed), who worked in aged care spoke about her Korean work colleague who once asked her, “Are all Muslims as good as you or is it only you? And I said, ‘no, all Muslims are good’ to which she replied, ‘I’m not scared of you, but I’m scared of Muslims’.” Wahida wondered why mainstream Australians did not know accurate information about Muslims and their culture even though there are so many Muslims in Australia. She described how her recent experience trying to get a permanent position was aborted due to her being a Muslim applicant, “My [employment] agency sent me to the [child-care] center not far from my house, and I worked there for that day. And they showed me [the place], they are nice to me [to my face], but they are not [actually nice]. When I finished the job, they rang the agent back and said, ‘Hey guys, why did you send us a Muslim lady?’” Regardless of the consequences on employment, not wearing the head scarf was not an option for Farida, “I had a lady come up to me and she said, ‘Can you not live without the head scarf? Can you put it away?’ and I said, ‘No, if I have to put away the head scarf, I have to find another job.’ You know, it’s not an option.”

The employed Somali female focus group concluded with the women blaming discrimination and the resulting difficulty gaining employment on Islamophobia (fear of Islam) among some Australians. All the women, employed and unemployed, perceived themselves as being disadvantaged and marginalized due to their visible religious dress; Afsana (38, unemployed) lamented, “I’m going to be sick without a job. I don’t like being unemployed. It’s not good for the health…. [No] money. I have to work and I’ve got no work.”

Discussion

Past research has documented the important role that English language acquisition plays in Somali former refugee employment (see Hebbani & Colic-Peisker, 2012). However, the findings from this focus group indicate that religion can play an even more vital role in Somali refugee employment outcomes. There seem to be differences between the sexes when it comes to the implications of Islamic visible difference. Based on the narratives from employed and unemployed women presented above, it appears that visible difference caused by their Islamic dress (jilbab and hijab) may impact some Somali women’s employment. The Somali men, on the other hand, may be more disadvantaged due to other religious markers such as having a Muslim name and being associated with negative connotations of “Somali”. Somali men, for the most part, wore traditional Western clothing, and were not immediately visibly identifiable as being Muslim. This is supported by Dunn and colleagues’ (2007) work which also shows that in Australia, “hijab-wearing Islamic women have reported higher rates of racist incivilities and attacks than have Islamic men or those women not wearing forms of cover,” (p. 568).

Somali men and women are dealing with the direct and indirect implications of being Muslim, through perceptions of covert discrimination, resulting in under-employment and unemployment. These findings are in line with past research which has acknowledged the impact of Islamophobia on Muslim employment in Australia (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2007; Poynting & Mason, 2007). Statistics from 2001 (Tilbury, 2007) reported that the unemployment rate for Australian Muslims was significantly higher than the unemployment rate for all Australians. A report recently released by the Australian Human Rights Commission (2010) documented how the barriers that African Muslim women faced when looking for employment was compounded, “African Muslim women, particularly those who wore the hijab, reported experiences of discrimination” (p. 34).

These reports also showed that as Muslims, religion played a major role in Somali identity and negotiating that identity for some was not an option. A conservative Australian society and misrepresentation of Somalis and Muslims in Australian media was seen to cause underemployment and/or unemployment combined with perceived discrimination.

These findings are, however, tempered by limitations. Given the small sample size, it would be valuable to increase the number of participants and include participants from other geographical areas. A longitudinal study would also yield interesting data with regards to employment outcomes and the resulting impact on participants’ lives, as would a study that compared Muslim refugee employment-seekers with non-Muslim refugee employment-seekers (ones with similar education background, similar difficulties with English, etc.). In addition, it is worthwhile to investigate further the impact of religious dress on Somali women’s employment. Finally, the findings noted in this study are participants’ perceptions with regards to discrimination, and need to be viewed in this light.

References

- Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21, 166-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

- Akou, H. M. (2004). Nationalism without a nation: Understanding the dress of Somali women in Minnesota. In Jean Allman (Ed.), Fashioning Africa: Power and the politics of dress, (pp. 50-63). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2007). 2006 Census Tables: Religious affiliation by age. Retrieved from http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ViewData?action=404&documentproductno=0&documenttype=Details&order=1&tabname=Details&areacode=0&issue=2006&producttype=Census Tables&javascript=true&textversion=false&navmapdisplayed=true&breadcrumb=TLPD&&collection=Census&period=2006&productlabel=Religious Affiliation by Age - Time Series Statistics (1996, 2001, 2006 Census Years)&producttype=Census Tables&method=Place of Usual Residence&topic=Religion&

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2010). In our own words -- African Australians: A review of human rights and social inclusion issues. Retrieved from http://www.hreoc.gov.au/africanaus/review/index.html

- Campbell, E. H. (2006). Urban refugees in Nairobi: Problems of protection, mechanisms of survival, and possibilities for integration. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19, 396-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fel011

- Colic-Peisker, V. (2009). Visibility, settlement success and life satisfaction in three refugee communities in Australia. Ethnicities, 9, 175-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468796809103459

- Colic-Peisker, V., & Tilbury, F. (2003). “Active” and “passive” resettlement: The influence of support services and refugees’ own resources on resettlement style. International Migration, 41(5), 61-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-7985.2003.00261.x

- Colic-Peisker, V., & Tilbury, F. (2007). Integration into the Australian labour market: The experience of three “visibly different” groups of recently arrived refugees. International Migration, 45(1), 59-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00396.x

- Constable, J., Wagner, R., Childs, M., & Natoli, A. (2004). Doctors become taxidrivers: recognising skills-not as easy as it sounds. Retrieved from http://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/25577/Recognising_Skills_-_not_as_easy_as_it_sounds.pdf

- Correa-Velez, I., & Onsando, G. (2009). Educational and occupational outcomes amongst African men from refugee backgrounds living in urban and regional southeast Queensland. The Australasian Review of African Studies, 30(2), 114-127.

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship. (2008). Settler arrivals, 1997-98 to 2007-08; Australia: States and territories. Retrieved from http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/settler-arrivals/settler_arrivals0708.pdf

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship. (2009). Immigration update 2007 – 2008. Retrieved from http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/immigration-update/update_june08.pdf.

- Droogsma, R. A. (2007). Redefining hijab: American Muslim women's standpoints on veiling. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 35, 294-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00909880701434299

- Dunn, K. M., Klocker, N., & Salabay, T. (2007). Contemporary racism and islamophobia in Australia: Racializing religion. Ethnicities, 7, 564-589. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468796807084017

- Gorman, D., Brough, M., & Ramirez, E. (2003). How young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds experience mental health: Some insights for mental health nurses. International Journal of Mental health Nursing, 12, 194-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00289.x

- Guerin, B., Guerin, P., Diirye, R. O., & Abdi, A. (2005). What skills do Somali refugees bring with them? New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 30(2), 37-49.

- Hebbani, A., & Colic-Peisker, V. (2012). Communicating one’s way to employment: A case study of African settlers in Brisbane, Australia. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33, 527-547. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2012.701609

- Hebbani, A.,&Wills, C. (2012). How Muslim women in Australia navigate through media (mis)representations of hijab/burqa. Australian Journal of Communication, 39, 87-100.

- Hopkins, L. (2009). Media and migration: A review of the field. Australian Journal of Communication, 36(2), 35-54.

- Jelle, H. A., Guerin, P., & Dyer, S. (2006). Somali women's experiences in paid employment in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 31(2), 61-69.

- Kabir, N. (2006). Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Australian media, 2001-2005. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 26, 313-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602000601141281

- Koshen, H. I. A. (2007). Strengths in Somali families. Marriage & Family Review, 41(1), 77-99.

- McMichael, C., & Manderson, L. (2004). Somali women and well-being: Social networks and social capital among immigrant women in Australia. Human Organization, 63(1), 88-99.

- Middle East Policy Council. (2002). Arab World Studies Notebook ‘Muslim Populations Worldwide’. Retrieved from http://archive.is/hUMcQ

- Mishra, S. (2007). ‘Saving’ Muslim women and fighting Muslim men: Analysis of representations in The New York Times. Global Media Journal, 6(11), Retrieved from http://lass.purduecal.edu/cca/gmj/fa07/gmj-fa07-mishra.htm.

- Navarro, L. (2010). Islamophobia and sexism: Muslim women in the western mass media. Human Architecture, 8(2), 95-114.

- Nilsson, J. E., Brown, C., Russell, E. B., & Khamphakdy-Brown, S. (2008). Acculturation, partner violence, and psychological distress in refugee women from Somalia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 1654-1663. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260508314310

- Poynting, S., & Mason, V. (2007). The resistible rise of Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim racism in the UK and Australia before 11 September 2001. Journal of Sociology, 43(1), 61-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1440783307073935

- Rout, M. (2009, October 30). Jihad’s motley crew. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/features/jihads-motley-crew/story-e6frg6z6-1225792580038

- Ruby, T. F. (2006). Listening to the voices of hijab. Women’s Studies International Forum, 29(1), 54-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2005.10.006

- Sadouni, S. (2009). ‘God is not unemployed’: Journeys of Somali refugees in Johannesburg. African Studies, 68, 235-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00020180903109615

- Tilbury, F. (2007). ‘Because of our appearance we are always suspect’: Religious discrimination in the Australian employment market. Refereed proceedings of The Australian Sociological Association/Sociological Association of Aotearoa,New Zealand, Auckland, December 4-7. Available at: http://www.tasa.org.au/conferences/conferencepapers07/papers/226.pdf

- Tilbury, F., & Colic-Peisker, V. (2006). Deflecting responsibility in employer talk about race discrimination. Discourse Society, 1, 651-676. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0957926506066349

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2009). UNHCR Somalia Fact Sheet November 2009. Retrieved from http://www.google.com.au/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&eENTITY=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDMQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.somaliweyn.org%2Fpages%2Fnews%2FNov_09%2FUNHCR_Somalia_Fact_Nov_2009.pdf&ei=GRz8UsfRLISlkQXrmYD4Aw&usg=AFQjCNHceFLTgs9gkTF8mGlLyXP2kQCamw&sig2=8yIS_IL1iJg6Jd9iuMItcg&bvm=bv.61190604,d.dGI&cad=rja

- United Nations Development Programme [UNDP] (2009). Human development report, overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2009_EN_Complete.pdf

- Valentine, G., & Sporton, D. (2009). `How other people see you, it's like nothing that's inside': The impact of processes of disidentification and disavowal on young people's subjectivities. Sociology, 43,735-751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038509105418

- Worthington, A. (Producer). (2009). Somali Australians – Overview [Television broadcast]. Sydney: SBS.

- Yusuf, S. O. (2005). The educational and employment aspirations of Somali high-school students in Melbourne: Some insights from a small study. Fitzroy, VIC: Ecumenical Migration Centre of the Brotherhood of St Laurence

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Helen Bristed for assisting with the female focus groups and the assistance of Jayson McNamara in preparing the review of literature.

Notes

ABS (2007) Country of Birth of Person (full classification list) by Sex – Australia

ABS (2007) Country of Birth of Person (full classification list) by Sex – Victoria. There were 2626 Somali-born residents in Victoria in 2006.

In 1998, there were 688 Somali entrants to Australia and in 2008 there were 156 Somali entrants to Australia.

In 1998, there were 48 Somali entrants to Queensland and in 2008 there were 27 Somali entrants to Queensland.

ABS (2007) Country of Birth of Person (full classification list) by Sex – SE Outer Brisbane

ABS (2007) Country of Birth of Person (full classification list) by Sex – Queensland.

This includes the birth of children in foreign refugee camps, citizenship in second or third nations and the subsequent, formal migration of settlers who are no longer refugees or nationals of their country of birth once they arrive to Australia. Many Somalis get identified in the census as coming from the country in which they were refugees rather than their country of origin (i.e., Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Egypt).

In 2007, an Australian cameraman, Nigel Brennan was kidnapped in Mogadishu and released 15 months later in November 2009, after being held at ransom; this story was significantly covered by Australian media throughout the time in captivity.

Please see Hebbani and Colic-Peisker (2012) for the impact of English proficiency on refugee employment outcomes.

Colic-Peisker (2009) explains the difference between “visibility” and “race” by noting that the term visibility is broader, less ambiguous and less value-laden than the scientifically discredited notion of race.

This could be attributed to the comparatively low levels of English proficiency among the unemployed participants as compared to the employed focus group participants.