Opening Up Institutional Repositories: Social Construction of Innovation in Scholarly Communication

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This paper focuses on institutional repositories as a case study to examine the design of a new scholarly communication technology from a social constructivist perspective. Institutional repositories are online databases of scholarly materials such as articles, reports, datasets to enable and foster sharing, discovery, and archiving of scholarly resources produced at a given institution. As a scholarly communication mode, institutional repositories represent a particularly interesting case to examine as they incorporate both normative and ideological agendas and illustrate how technical products embody social goals and power relationships. Although the analysis is based on institutional repositories, the theoretical approach is relevant to various information and communication technology development efforts aiming to introduce new tools in support of scholarly communication. The paper’s discussion draws from the social construction of technology theory, actor-network theory, and the socio-technical interactions networks model. Such a social constructivist framework provides an effective method for uncovering multiple perspectives that frame the design and appropriation of institutional repositories.

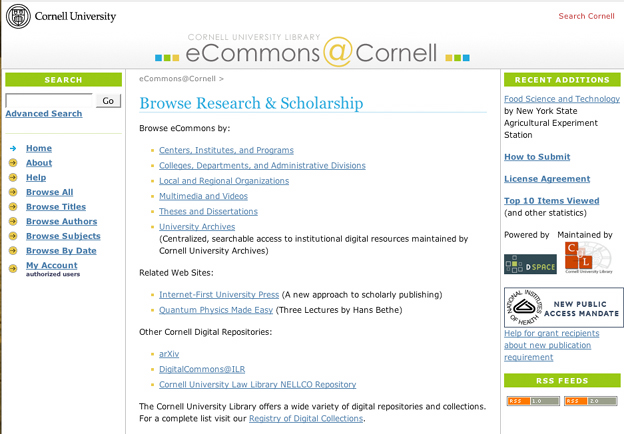

With the Web’s ubiquity and its ability to make new digital authoring applications accessible, a wide range of intellectual materials ends up in some form of online publication. At the same time, an expanded networking capacity coupled with the increasing availability of open source tools encourages new forms of online publishing and archiving. Responding to this trend, institutional repositories (IRs) provide a set of services for the management and dissemination of digital materials created by an institution and its community members (Lynch, 2003). IRs contain and organize a variety of scholarly content such as reports, articles, books, visual images, datasets, course materials, and audio and video resources. According to a 2007 survey (Markey et al., 2007), there are close to 200 academic institutions in the United States that either have IRs or are in the process of developing them. IR systems[1] are designed to collect, manage, distribute, and preserve academic products of educational and research institutions. Common features of IRs can be seen in the Cornell University Library’s IR, eCommons: see figures 1 and 2.

The goal of this paper is to explore IRs from a social constructivist perspective in order to understand the choices made in their design and implementation. The initial research and publications about digital repositories in the early 2000s focused on system design, interoperability standards, and technical requirements, and currently there is a mounting interest in evaluating IR technologies and services from a usability standpoint (Ferreira et al., 2008). However, only a handful of studies examine IR technology from sociocultural perspectives.

As Williams and Lawton (2005) point out, much of the current research and literature focuses on the perceived benefits of IRs as a new scholarly communication technology, such as widening access to scholarly information, reducing the costs of producing and acquiring scholarly publications, and gaining control of the scholarly communication process from commercial publishers. There is also extensive literature on technical aspects of digital repositories in information, computer, and library science fields with discussions on issues such as system architecture, interoperability, metadata, and digital preservation. However, little attention has been devoted to understanding the negotiation process surrounding IR development and implementation efforts from the perspective of relevant groups’ shifting or aligning interests.

This paper attempts to consider how sociocultural approaches can reveal deeper insights to help us understand the IR technology development and deployment efforts. The analysis draws on my involvement with the digital repository development and assessment efforts at the Cornell University Library and in various national and international efforts during the last five years. In addition, the paper is informed by ethnographic observations and interviews with 25 scholars about their scholarly practices and interdisciplinary collaboration patterns.[2] The interdisciplinary discussion is supported and illuminated by the social studies of science literature, which provides valuable lenses for examining multiple perspectives that frame the design and appropriation[3] of digital repositories. Also included in the analysis is a literature review of information and library science materials to explore various perspectives in regard to development and use of IR services.

After briefly positioning the role of IRs in scholarly communication, the paper focuses on applying a social constructivist approach to explore the process that underlies the development and introduction of IRs. The paper’s theoretical discussion draws from social construction of technology, actor-network theory, and socio-technical interaction networks. The paper concludes with reflections on the role of a social constructivist framework in illuminating the design and implementation process of a scholarly communication technology.

Innovation in Scholarly Communication

Responding to the changes triggered by the increasingly networked environment and publishing industry consolidations, the research library community has been actively exploring innovative roles for carrying on their stewardship responsibilities in a digital realm (Brown, Griffiths, and Rascoff, 2007). The IR systems were introduced in the early 2000s as a way to introduce a new scholarly communication model that builds on new networking and storage capabilities and rapidly expanding digital content. At the heart of repository development efforts is the aim of the information and library science community to modify the existing scholarly communication model by supplementing and even in some cases supplanting the existing scholarly dissemination methods that depended heavily on commercial publishers (Walters, 2007; Thomas, 2006). A majority of the existing IRs aspire to promote and operationalize open access principles to alter the economic model that underlies the current publication system.

IR systems and services also portend new roles for librarians in an increasingly digital world. Walters writes, “when libraries create institutional repositories (IRs), they are reinventing themselves” (2007, p. 213). This is a sentiment commonly expressed in the library science literature, as IRs are seen as shifting the balance from being passive receivers of scholarly outputs from publishers to active disseminators, allowing libraries to participate in the process as publishers.

As will be illustrated through the following sociocultural analysis, although the technical features of IRs are critical for user acceptance, in and of themselves they are not sufficient to determine the scholarly community’s appropriation of IR technologies. The adoption and adaptation of information and communication technologies are often tightly coupled within the context of a specific implementation and influenced by the existing work culture and user attitudes. Therefore, IRs should not be examined from a predominantly technological perspective. The functionalities and affordances introduced by IRs need to be positioned by taking into consideration the social and cultural factors that have shaped scholarly conduct for several centuries.

Social Construction of Technology

Social construction of technology as a theoretical framework provides a model to study the social context of technological innovation. Its key assumption is that innovation is a complex process of co-construction in which technology and users negotiate the meaning of new technological artifacts (Pinch and Bijker, 1987). Central to social construction of technology is the concept that there are choices inherent in both the design of technologies and their appropriation by relevant groups. Technology deployment cannot be understood without comprehending how a specific technology is embedded in its social context.

There are several studies based on the social construction of technology that illustrate the implementation of the framework on emerging information and communication technologies to support a richer analysis of outcomes through the inclusion of broader social, cultural, and political factors (Dayton, 2006; Cooley, 2004; Jackson, Poole, and Kuhn, 2002; Mitev, 2000). An inspiring example is set by Bohlin (2004) with his use of the social construction methodology in analyzing the current transformation in scholarly communication with a focus on e-print repositories. He examines how arXiv[4] as a digital repository is embraced by the high-energy physics community.

The following discussion involves the application of the three key social construction concepts to shed light on the negotiation process involved in IR development and adoption. Analyzing IRs from the perspectives of relevant social groups, interpretative flexibility, and stabilization uncovers a range of social and cultural contingencies that are crucial in determining the acceptance of the application by the scholarly community.

Relevant Social Groups

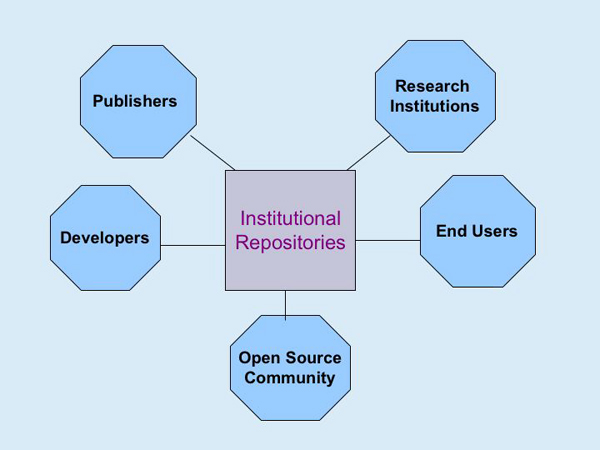

At the foundation of the explanatory framework of the social construction of technology is the concept of relevant social groups, which share a particular set of meanings about a technology or an information system. In the case of IRs, the relevant social groups include a wide range of stakeholders who have different interpretations of the application based on their needs, roles, goals, values, and motivations. The stakeholders also vary in their ability to influence the development, application, and acceptance of IR applications. It is important to note that this paper identifies only the key stakeholders, as the goal is to demonstrate the interpretative flexibility rather than providing a full analysis.[5] As shown in Figure 3, the key relevant groups include the developers, research institutions, users, open source community, and publishers. These groups are described in Table 1.

| DEVELOPERS | Developers (information technologists and librarians) gather user requirements and develop, test, and maintain the system code. |

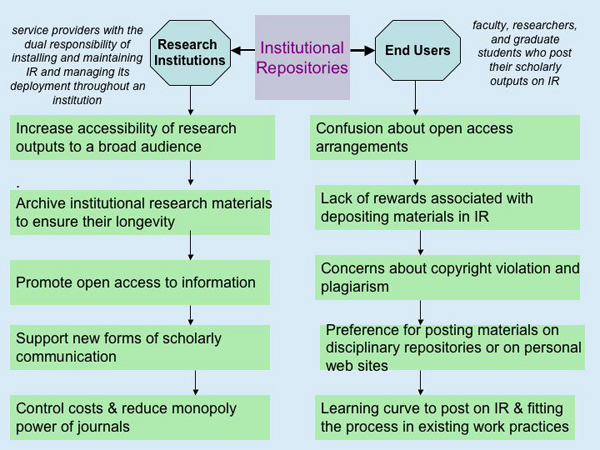

| RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS | Research institutions such as libraries assume the service provider role with the dual responsibility of installing and maintaining IR systems and managing their deployment in their organizations through outreach and training programs. |

| USERS | Users encompass a wide range of academic practitioners including faculty, researchers, and graduate students. They are “consumers of the service” both as contributors of scholarly outputs for archiving and as users of information deposited in the IR. |

| OPEN SOURCE COMMUNITY | Programmers and systems analysts who are interested in contributing to public open access software development efforts to support collaborative application development and maintenance. |

| PUBLISHERS | Publishers, including learned societies, commercial publishers, individual authors, and university presses, who have been in the business of publishing through formal publication mechanisms (e.g., journals, books). This group also includes those who are now in a position to be publishers due to the opening of the publishing market to a wider range of participants.[6] |

Interpretative Flexibility and Technological Frames

According to the social construction of technology theory, technologies are culturally constructed and interpreted. The interpretative flexibility notion denotes both variations in understanding of a technology and the flexibility of the design process. Bijker’s (1987) concept of a technological frame refers to the concepts and techniques employed by a community for addressing needs, and is intended to apply to the interactions among various actors. Technological frame denotes the commonality of perception and approach in a particular group and is composed of elements such as tacit knowledge, challenges faced, norms, technical skills, institutional policies, and practices. It provides the context in which a new technology is interpreted.

There is growing evidence that adoption of IRs by scholars is slow and the perceived benefits are not immediately obvious to the scholarly community (Ferreira et al., 2008; Davis and Connelly, 2007; Thomas and McDonald, 2007; Chan, 2004). Although there is a common desire to facilitate and enhance scholarly communication, the following examples based on DSpace institutional repository software[7] demonstrate the variations in the IR stakeholders’ technological frames that present reverse salients[8] in widespread adoption of the technology.

1. IR as a Tool for Institutional Asset Management

The developers have a unified vision of providing a way to manage and preserve research materials and publications in a professionally maintained repository to enable greater visibility and accessibility over time. Some among them also aim to promote open-source publishing systems in order to correct the imbalance[9] in the scholarly communication environment. They perceive the benefits of IRs to include scholars’ ability to get their research results out quickly, reaching a worldwide audience, archiving course materials, and keeping track of their publications (Smith et al., 2003).

DSpace, as the pioneering and currently the most common IR software, provides an illustrative example of the developers’ technological frame. DSpace was developed in an academic context with the notion of building communities that represent different academic departments, research centers, labs, etc. (see Figure 1 showing Cornell’s DSpace-based installation). The goal was to manage academic assets based on an information model that represents an institution’s organizational structure. The DSpace developers emphasized the local community-building aspects of DSpace and made a deliberate decision to use the term institutional repositories in representing and promoting the service category.

However, some faculty members are put off by the concept of institutional and may hesitate to share their documents on an open access system run by an institution. The need for supporting inter-organizational networks is perceived differently by developers and users of DSpace. While the library community appreciates institutional networks, academics feel closer to their own disciplinary networks. In my interviews, faculty members told me that at the heart of their reaction are concerns about quality (which is an essential criterion for scholarly outputs) and potential copyright infringements. Several faculty members I talked with during my study expressed the need to stay closer to their special communities through networking and information sharing both for professional development and for building reputation. Also, many of them expressed their preference for posting articles on their own Web sites rather than institutional repositories. The separation of practitioners into disciplines with distinct cultures and needs has kept scholars from converging and advocating more open and cost-efficient information-sharing methods (King et al., 2006).

2. DSpace as an Open Access Tool

It is important to note that the DSpace development community has had a political agenda too. The digital library community advocated for alternative channels of scholarly communication because of what they characterized as the “scholarly communication crisis,” the increasing publication prices, prohibitive copyright implementations, and commercial publishers’ lack of long-term management strategies for digital content. DSpace has been positioned as a new strategy to influence the existing publication models and to present an alternative mode to control the economic threats perceived by the library community from commercial publishers (Chan, 2004). However, most faculty members are not as much concerned about the library community’s scholarly communication crisis and do not perceive an immediate need to modify the existing scholarly communication system (Troll Covey, 2007).[10] Some scholars see open access as undermining the traditional scholarly communication system and eroding prestige that is guarded and reinforced by scholarly publishing and university tenure boards (Kennan and Cecez-Keemanovic, 2007).

Based on interviews and ethnographic observations involving faculty and researchers, Foster and Gibbons (2005) conclude that IRs fail to appear compelling and useful to the authors and owners of scholarly content (users).[11] Even the terminology used in promoting DSpace (IR, digital preservation, metadata, open-access, interoperability) presents confusing concepts for faculty and is seen as professional jargon. The benefits of IRs thus far seem to be very persuasive only to hosting institutions such as research libraries. Kim’s (2007) preliminary survey of 67 professors concluded that faculty members who intended to contribute to the IR in the future agreed more strongly with of the concept of open access. The pilot study also pointed out that the influence of grant funders lowers faculty motivation for IR contribution.

Boczkowski’s[12] 2006 study of the cultural and political dynamics in the adoption of institutional repositories revealed that librarians and academics approach the technology from different points of view. While the information science practitioners such as librarians are trying to drive change, the more powerful academic community is refusing to modify their existing practices. The library community has built a solution based on a perceived problem (scholarly communication crises); but because the academics do not observe a problem that needs to be fixed, they are reluctant to adopt practices and policies imposed on them by others in the institution.

Figure 4 lays out the perceptions of the two relevant groups in regard to the IR’s role in facilitating, sharing, and archiving scholarly materials. The discrepant interpretations of relevant groups inevitably create a natural tension in the development and deployment efforts because of differences in expectations. Also, because the technology is new and still changing, the technological frameworks of end users appear to be evolving and there are not yet any significant alignments among different frames.

Stabilization and Closure

According to social construction theorists, as a technology such as IR evolves, the interpretation and design flexibility goes through a closure process as it stabilizes. The stabilization may occur through a rhetoric closure in which the groups see the problem as solved when the technology addresses a number of stakeholders’ needs. Alternatively, closure may occur due to the redefinition of the problem or appearance of a new problem that needs to be solved through design (Pinch and Bijker, 1987). Closure implies that some particular interpretation dominates. Nevertheless, closure is not permanent; the process may be reopened as existing social groups are transformed or new stakeholders are introduced.

Although applying social construction of technology theory to stabilized initiatives seems to be the norm, it is not unusual to apply the theory to an open-ended and contingent process such as IR development and deployment.[13] Pinch and Bijker (1987) propose that the theory framework should apply to open and ongoing technological controversies as well as stabilized ones. The value of using social construction theory before the stabilization process is the opportunity to analyze the social negotiations in a predictive rather than purely descriptive manner. Diagnosing the gaps among the views held by major stakeholders leads to a more realistic assessment of factors involved in the adoption of a technology, and some of those factors can be useful to ongoing design and promotion processes.

Relevant social groups not only characterize technological problems in their own ways, but they also assign success or failure to particular technical systems differently based on how their needs are met (Cooley, 2004). In the case of scholarly communication technologies, new systems and standards continue to appear, creating a dynamic market. Some argue that sooner or later open access will be the predominant form of scholarly information dissemination and IRs will prevail. However, social construction of technology theory contests such deterministic claims and states that the utility of a new technology depends upon cultural patterns and social conventions of multiple groups (Bohlin, 2004). Even if IRs as systems and services have the potential of solving the problems, they will not be widely used if academics do not agree that there is a problem and that IRs can address it.

Actor-Network Theory

Actor-network theory emphasizes mediation-in-action in heterogeneous systems of humans, tools, and communities (Bratteteig and Gregory, 2001; Latour, 1992). Developed by Callon, Latour, and Law, this theory maps both human and non-human elements of an activity into a coherent network. For instance, the scholarly publishing process involves interactions among human agents such as publishers and authors in addition to semiotic elements such as editorial guidelines and peer review, and artifacts such as articles. Actor-network methodology is especially suitable for analyzing the scholarly communication process, as the model was originally based on Latour’s observations of the production of scientific work, which is similar in many ways. Figure 5 demonstrates the rich network of IRs from an actor-network theory perspective. The web of interdependencies includes elements such as funding sources and disciplinary practices. Each element is critical for the robustness of the system. Although Figure 5 maps relationships in a fixed configuration, it is a dynamic model and the elements relate to each other in multiple ways. For instance, promotion guidelines are also determined by disciplinary practices. The essence of the model is to highlight the compound and crucial nature of dependencies.

As shown in Figure 5, actor-network theory is an effective model for describing how technical solutions are interwoven with organizational issues, power and political relations, and external factors such as policies and regulations (Mitev, 2000). Success is often defined not only by its being the right answer to the problem addressed, but also by how it supports the actors. Each actor translates the technology and interprets it according to his or her context and needs. In the case of an IR, the system’s architecture must be aligned with the work practices and cultures of the relevant groups for the system to gain acceptance.

Kennan and Cecez-Kecmanovic (2007) explore the emergence of IRs as a new publishing practice and look at the pressures to preserve traditional publishing modes through an actor-network theory lens. According to their analysis, IR technologies combined with open access principles are opening the “black box”[14] of scholarly communication alliances for new negotiations. Their application of the theory to Australian research repositories[15] illustrates the importance of defining the problem and translating it[16] to effectively persuade pertinent actors that IRs will enhance their scholarly communication process. Some scholars with aligned interests enroll and deposit their scholarly materials in an IR. However, many of them cannot see benefits behind reconciling and changing their scholarly communication patterns. Kennan and Cecez-Kecmanovic conclude that in the case of Australian research repositories, translation is not a smooth process: new publishing patterns and pressures to preserve the old network are emerging simultaneously. The new IR actor network is impinging on the old scholarly publishing actor network, and scholars are not moving from one to another in a straightforward process. This is due not only to IRs’ conflicts and misalignments with existing scholarly practices, but also due to the immature state of the features and functionalities of IR technologies.

Another contribution of an actor-network theory framework in shedding light on the social construction of IRs is Latour’s (1992) notion of “prescription,” which is the behavior imposed back onto the human by the non-human delegates. In the case of IRs, human delegates are scholars and the non-human delegate is a given IR system. The utilization of an IR is dependent on scholars depositing their materials in it. Although at some institutions library staff gather and bulk-load scholarly materials of their faculty without reliance on scholars, most IRs must persuade researchers to independently deposit their output on their own to make the collection-building process sustainable.

Socio-Technical Interactions Networks Theory

The heuristic frameworks of social construction of technology and actor-network theories can be extended by adding the socio-technical interactions networks theory as an additional perspective. This social informatics strategy was developed by Rob Kling as an alternative way to investigate the use of information and communication technologies in an interdisciplinary manner and address some of the limitations of social constructivist methods (Oostveen, 2007). For instance, Kling points out that information and communication technologies are transformative and therefore can raise questions about social choices and value conflicts. He argues that social scientists have the responsibility not only to study a technology, but also to talk about its social consequences.

Kling’s theory draws on social construction and actor-network theories to identify relevant groups, understand interpretative flexibility, and examine the translation and enrollment process (Meyer, 2006). Because of its problem-driven approach, socio-interactions network theory expands the social constructivist approach by including in its framework business models and sustainability operations of the technologies (Meyer, 2006). For that reason, Kling’s studies often include an analysis of funding models. In his examination of digital repositories, he argues that technological developments such as fast Internet connections and intuitive interfaces themselves will not overcome issues embedded in social structures (Kling, 2004; Kling et al., 2003). He cites long-standing institutional arrangements, business models supporting scholarly communication systems, and vested interests of gatekeepers such as publishers in determining user acceptance and appropriation behavior.

Role of Structures and Sustainability in Institutional Repository Design and Deployment

Both social construction and actor-network theories are in some ways limiting, in that they do not sufficiently take into account the structures, the formal and informal rules that establish distinctive resources, capacities, opportunities, and constraints (Kleinman, 1998). Social construction of technology emphasizes agency at the expense of neglecting or undervaluing the role of existing structures that may support or inhibit unfolding technological innovations (Dayton, 2006; Klein and Kleinman, 2002; Brey, 1997).[17] In their study about the social construction of the automobile in rural America, Kline and Pinch (1996) point out that the theory does not inherently neglect the social structure and power relationships. However, both Klein and Kleinman (2002) and Brey (1997) argue that the symmetry principle[18] in social construction theory may discourage political and cultural analysis of choices about technology. Williams and Edge (1996) point out a related shortcoming of actor-network theory: that it does not take into account the nature and influence of broader social and economic structures of power and interests, because of its emphasis on agents.

“Approaches that try to ‘move’ faculty and their deeply embedded value systems directly toward new forms of archival systems are destined to fail.”

The IR case study strongly demonstrates the critical role of deeply institutionalized structures in shaping acceptance or rejection of information and communication technologies by both producers and consumers of scholarly materials. Such structural characteristics are revealed in the technological frames of relevant groups. For instance, the main barrier for institutional repositories is lack of compelling incentives for authors to change publishing behavior that has been shaped as a result of centuries-long practices and norms. A study by the Center for Studies in Higher Education (King et al., 2006) concludes that approaches that try to “move” faculty and their deeply embedded value systems directly toward new forms of archival systems are destined to fail. The complexities and traditions in each discipline determine their use of information technology, resulting in different sharing and archiving models and systems (Kling and McKim, 2000).

Another example of the critical position of social and cultural structures in scholarly communication is the role of commercial publishers, which have been the principal route for disseminating scholarly products for several centuries. The peer review, editing, and marketing of publications by profit and nonprofit publishers are perceived to add value to scholarly output. Traditionally, publishers hold perpetual rights over copyright in return for certification of scholarly output through formal publishing. The publishing process signifies a level of quality and provides credentials for the scholar in the promotion and tenure process (Fjällbrant, 1997).

Structures are both influential and amendable. One of the core concepts of structuration theory[19] is dialectic of control, which states that agents are not fully passive entities and they have the power to change the structures that guide their behavior (Miller, 2002). An excellent example of dialectic of control in scholarly communication is demonstrated by the Modern Language Association’s task force to examine current standards and emerging trends in publication requirements for tenure and promotion. The task force recommended that departments and institutions recognize the legitimacy of scholarship produced in new media and venues such as IRs (MLA, 2006). Another instance of structural change that will have impact on IRs is the recent decision of the National Institutes of Health to require all investigators funded by the agency to submit an electronic version of their final manuscripts to the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed Central[20] (NIH, 2008). Both of these examples illustrate the importance of structural factors in determining the role of information and communication technologies in scholarly communication.

The notion of dialectic of control is analogous to social constructivists’ stance on mutual shaping of technology, the ongoing interaction between humans and technological artifacts and the reciprocal nature of shaping. Structural characteristics, similar to infrastructure, are also reciprocal and evolve responding the changing landscapes.

Inside Institutional Repositories: Concluding Remarks

“Most of the impediments to widespread implementation relate directly to the gap between the developers’ and potential users’ perception of the scholarly communication landscape.”

Currently, there are several open source IR systems in use that are equipped with rich sets of functionalities to facilitate depositing, accessing, and retrieving scholarly materials. However, Rieh et al.’s (2007) census of IRs reveals a great level of uncertainty underlying IRs in regard to practices, policies, and content. As Foster and Gibbons (2005) point out, without content, an IR is just a set of empty shelves. Thus far, IRs have only partially fulfilled their original intent, and their adoption by potential users thus far has been limited: the quantity of deposited content remains quite modest. Although the present situation can be partially traced to the structural issues such as copyright and tenure publication requirements, most of the impediments to widespread implementation relate directly to the gap between the developers’ and potential users’ perception of the scholarly communication landscape.

IR development and deployment efforts to date have been predominantly driven by digital libraries. IRs provide a provocative case for examining the consequences of system development primarily based on perceptions, background, and expectations of a particular community of practitioners—in this case information and library scientists. It is an example of a technologically sound system that is facing challenges being embraced and adopted by intended end users. The problem is the misalignments between developers’ inscriptions of end users—their projection of users’ behavior in order to create the user interface—and the actual end use patterns. As Madeleine Akrich writes, “Designers... define actors with specific tastes, competences, motives, aspirations, political prejudices, and the rest, and they assume that morality, technology, science, and economy will evolve in particular ways.” (1992, p. 208) She describes this process as “inscribing” this vision of users in the technical content of a technology.

There appears to be a level of determinism associated with the developers’ technological frames because of their assumption that IRs’ intrinsic characteristics and functionalities control and direct change as independent agents. IRs do not seem to be following a natural trajectory but rather are being defined by expressed needs of relevant groups and the evolving structural elements.

The open source IR development process has been ideological in the sense that the process is informed by the values and worldviews of its developers, who make a case for a scholarly publishing crisis. The information and library science community has perceived institutional repositories as a tool to introduce change to the scholarly communication process for digital content. The goal has been to modify the positions and perceptions of faculty on managing their intellectual materials. The ideological aspect of IR development brings to mind Winner’s (1985) position that technologies can contain political properties to impose new forms of order and behavior. However, as Joerges (1999) responds to Winner’s argument, although designers may try to inscribe values in technologies, such artifacts cannot fixate social relationships as defined by their designers. IRs provide an excellent example of this case.

The experience thus far indicates that IRs would become a more compelling and useful tool if they were aligned with existing faculty practices. Recent studies stress the importance of working with faculty closely to better understand their work habits and research context. An excellent example of this approach is provided by Maness et al. (2008) in their creation of personas to describe different classes of potential IR users to facilitate increased participation. Another potential strategy in introducing change is designing outreach programs to increase faculty awareness of the politics of current publication practices in order to make a case for the virtues of moving to another model that will continue to support their unique needs and work practices.

Social constructivist theories are valuable in redirecting our attention from technical and functional aspects of information and communication technologies to the work practices and sociocultural factors. Park (2008) links scholarly communication with science and technology studies frameworks and provides a compelling case for using such perspectives in bringing a socio-technical approach to studying the evolving nature of scholarship. Triangulation of relevant theories and methodologies provides deeper insights to understand the communication and negotiation processes involved in introducing a new technological solution. The social construction of technology theory is useful as a heuristic framework for examining the stakeholders and their technological frame to understand the factors in the negotiation and appropriation process. Actor-network theory further enriches the constructivist approach by encouraging us to consider mediation in action in a heterogeneous network of human and non-human elements. Another theoretical angle that could add value to the analysis involves including an economic theory to understand the impact of associated IR implementation costs in shaping consumer and producer attitudes. Socio-technical interactions networks theory is a first step in that direction as it includes sustainability as one of its assessment factors.

The central tenet of this paper is that the development of scholarly communication technology such as institutional repositories is open to sociological analysis not only in terms of how the IRs are being used, but also how they are being constructed and interpreted. Through analysis of sociocultural factors based on social theories, we can attain a better understanding of how information and communications technologies should be designed and implemented, and improve promotional activities to encourage their appropriation. As shown in the case of IR implementation, change is an outcome of social evolution as well as technical innovation. Information and communication technologies need to be designed, assessed, and promoted with an appreciation of their being a joint product of technical features and intergroup negotiations. To design effective information and communication technologies, we need to better understand the associations among the information practices, institutions, and the social and material foundation of the scholarly communication processes.

Oya Rieger is associate university librarian for information technologies at Cornell University Library. She oversees the Library’s digital repository development, digital preservation, electronic publishing, and e-scholarship initiatives. Her responsibilities also involve the coordination of the Library’s large-scale digitization collaborations. She is the coauthor of the award-winning Moving Theory into Practice: Digital Imaging for Libraries and Archives (Research Libraries Group 2000) and has served on several digital imaging and preservation working groups including co-chairing the development of ANSI/NISO Technical Metadata for Digital Images. Her recent publication in 2008 by CLIR focuses on the digitization challenges presented by large-scale digitization projects. She has a B.S. in Economics, an M.P.A., and an M.S. in Information Systems. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at Cornell’s Department of Communication. Her research interests focus on sociocultural aspects of the intersection of digital technologies and scholarly communication. She can be reached at oyr1@cornell.edu.

Acknowledgment

The article is based on a paper written for a graduate course taught by Professor Trevor Pinch at the Science and Technology Studies, Cornell University. The discussions he led in regard to how social relations and society get inside technology have provided me a new lens for exploring the evolving scholarly communication landscape. I also would like to thank him for reading and commenting on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

Akrich, Madeleine. 1992. “The De-Scription of Technical Objects.” In Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law, eds., Shaping Technology / Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, 205–24. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Association of Research Libraries. 1998. “Transforming Scholarly Communication: Introduction.” In Confronting the Challenges of the Digital Era: Membership Meeting Proceedings. 133rd Membership Meeting, Washington, D.C., October 14–16, 1998. Retrieved April 18, 2008, from http://www.arl.org/resources/pubs/mmproceedings/133mmcommintro

Bijker, Wiebe E. 1995. Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bohlin, Ingemar. 2004. “Communication Regimes in Competition: The Current Transition in Scholarly Communication Seen through the Lens of the Sociology of Technology.” Social Studies of Science 34 (3): 365–91.

Bratteteig, Tone, and Judith Gregory. 2001. “Understanding Design.” In B. Solveig, R. E. Moe, A. Mørch, and A. L. Opdahl, eds., Proceedings of the 24th Information Systems Research Seminar in Scandinavia (IRIS 24), Ulvik, Norway.

Brey, Philip. 1997. “Philosophy of Technology Meets Social Constructivism.” Society for Philosophy and Technology 2 (3–4). Retrieved May 1, 2008, from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/SPT/v2n3n4/brey.html

Brown, Laura, Rebecca Griffiths, and Matthew Rascoff. 2007. University Publishing in a Digital Age. Retrieved April 10, 2008, from http://www.ithaka.org/strategic-services/university-publishing

Chan, Leslie. 2004. “Supporting and Enhancing Scholarship in the Digital Age: The Role of Open-Access Institutional Repositories.” Canadian Journal of Communication 29 (3): 277–300.

Cooley, R. E. 2004. “The Social Construction of Technology and Information Systems.” Proceedings of the 9th UK Academy for Information Systems Conference, 121–129. Glasgow: Glasgow Caledonian University.

Davis, Philip M., and Matthew J. L. Connolly. 2007. “Institutional Repositories: Evaluating the Reasons for Non-use of Cornell University’s Installation of DSpace.” D-Lib Magazine 13 (3/4). Retrieved April 17, 2008, from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/march07/davis/03davis.html

Dayton, David. 2006. “A Hybrid Analytical Framework to Guide Studies of Innovative IT Adoption by Work Groups.” Technical Communication Quarterly 15 (3): 355–382.

Dourish, Paul. 2003. “The Appropriation of Interactive Technologies: Some Lessons from Placeless Documents.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 12 (4): 465–490.

Ferreira, Miguel, Ana Alice Baptista, Eloy Rodrigues, and Ricardo Saraiva. 2008. “Carrots and Sticks: Some Ideas on How to Create a Successful Institutional Repository.” D-Lib Magazine 12 (1/2). Retrieved April 18, 2008, from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january08/ferreira/01ferreira.html

Fjällbrant, Nancy. 1997. “Scholarly Communication: Historical Development and New Possibilities.” IATUL Proceedings 7: Scholarly Communication in Focus. Retrieved September 15, 2008, from http://internet.unib.ktu.lt/physics/texts/schoolarly/scolcom.htm

Foster, Nancy Fried, and Susan Gibbons. 2005. “Understanding Faculty to Improve Content Recruitment for Institutional Repositories.” D-Lib Magazine 11 (1). Retrieved May 2, 2008, from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january05/foster/01foster.html

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. “Elements of the Theory of Structuration.” In The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration, 1–40. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hara, Noriko, and Rob Kling. 2002. “Communities of Practice With and Without Information Technology.” Proceedings of the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 338–349. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Jackson, Michèle H., Marshall Scott Poole, and Tim Kuhn. 2002. “The Social Construction of Technology in Studies of the Workplace.” In Leah A. Lievrouw and Sonia M. Livingstone, eds., Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs, 236–253. London: Sage.

Joerges, Bernward. 1999. “Do Politics Have Artefacts?” Social Studies of Science 29 (3): 411–431.

Kennan, Mary Anne M., and Dubravka Cecez-Kecmanovic. 2007. “Reassembling Scholarly Publishing: Institutional Repositories, Open Access, and the Process of Change.” In Australian Conference on Information Systems: The 3 Rs: Research, Relevance and Rigour - Coming of Age, December 5–7, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1030964

Kim, Jihyun. 2007. “Motivating and Impeding Factors Affecting Faculty Contribution to Institutional Repositories.” Journal of Digital Information 8 (2). Retrieved June 30, 2008, from http://journals.tdl.org/jodi/article/view/193/177

King, C. Judson, Diane Harley, Sarah Earl-Novell, Jennifer Arter, Shannon Lawrence, and Irene Perciali. 2006. Scholarly Communication: Academic Values and Sustainable Models. Berkeley, CA: Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of California–Berkeley. Retrieved April 10, 2008, from http://cshe.berkeley.edu/publications/publications.php?id=23

Klein, Hans K., and Daniel Lee Kleinman. 2002. “The Social Construction of Technology: Structural Considerations.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 27 (1): 28–52.

Kleinman, Daniel Lee. 1998. “Untangling Context: Understanding a University Laboratory in the Commercial World.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 23 (3): 285–314.

Kline, Ronald, and Trevor Pinch. 1996. “Users as Agents of Technological Change: The Social Construction of the Automobile in the Rural United States.” Technology and Culture 37 (4): 776–795.

Kling, Rob, and Geoffrey McKim. 2000. “Not Just a Matter of Time: Field Differences and the Shaping of Electronic Media in Supporting Scientific Communication.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 51 (14): 1306–1320.

Kling, Rob, Geoffrey McKim, and Adam King. 2003. “A Bit More to It: Scholarly Communication Forums as Socio-Technical Interaction Networks.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 54 (1): 47–67.

Kling, Rob. 2004. “The Internet and Unrefereed Scholarly Publishing.” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 38: 591–637. Medford, NJ: Information Today.

Latour, Bruno. 1992. “Where Are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts.” In Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law, eds., Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, 225–258. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lynch, Clifford A. 2003. “Institutional Repositories: Essential Infrastructure for Scholarship in the Digital Age.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 3 (2): 327–336. Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/portal_libraries_and_the_academy/v003/3.2lynch.html

Maness, Jack M., Tomasz Miaskiewicz, and Tamara Sumner. 2008. “Using Personas to Understand the Needs and Goals of Institutional Repository Users.” D-Lib Magazine 14 (9–10). Retrieved September 15, 2008, http://dlib.org/dlib/september08/maness/09maness.html

Markey, Karen, Soo Young Rieh, Beth St. Jean, Jihyun Kim, and Elizabeth Yakel. 2007. Census of Institutional Repositories in the United States: MIRACLE Project Research Findings, CLIR Pub 140. Washington, D.C.: Council on Library and Information Resources. Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://www.clir.org/pubs/abstract/pub140abst.html

Meyer, Eric T. 2006. “Socio-Technical Interaction Networks: A Discussion of the Strengths, Weaknesses and Future of Kling’s STIN Model.” In Jacques Berleur, Markku I. Nurminen, and John Impagliazzo, eds., IFIP International Federation for Information Processing, vol. 223, Social Informatics: An Information Society for All? In Remembrance of Rob Kling, 37–48. Boston: Springer.

Mitev, Nathalie. 2000. “Toward Social Constructivist Understandings of IS Success and Failure: Introducing a New Computerised Reservation System.” In Proceedings of the Twenty First International Conference on Information Systems, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 84–93. Retrieved October 7, 2008, from http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=359640.359725

Modern Language Association Task Force on Evaluating Scholarship for Tenure and Promotion. 2006. Report of the MLA Task Force on Evaluating Scholarship for Tenure and Promotion. Retrieved September 24, 2008, from http://www.mla.org/tenure_promotion_pdf

Oostveen, Anne-Marie. 2007. Context Matters: A Social Informatics Perspective on the Design and Implications of Large-Scale e-Government Systems. Ph.D. diss., University of Amsterdam.

Park, Ji-Hong. 2008. “The Relationship between Scholarly Communication and Science and Technology Studies (STS).” Journal of Scholarly Publishing 39 (3): 257–273.

Pinch, Trevor J., and Wiebe E. Bijker. 1987. “The Social Construction of Facts and Artifacts: or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other.” In Wiebe E. Bijker, Thomas P. Hughes, and Trevor J. Pinch, eds. The Social Construction of Technological Systems: New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology, 17–50. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rieh, Soo Young, Karen Markey, Beth St. Jean, Elizabeth Yakel, and Jihyun Kim. 2007. “Census of Institutional Repositories in the U.S.: A Comparison Across Institutions at Different Stages of IR Development.” D-Lib Magazine 13 (11/12). Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/november07/rieh/11rieh.html

Smith, MacKenzie, Mary Barton, Mick Bass, Margret Branschofsky, Greg McClellan, Dave Stuve, Robert Tansley, and Julie Harford Walker. 2003. “DSpace: An Open Source Dynamic Digital Repository.” D-Lib Magazine 9 (1). Retrieved April 30 from http://dlib.org/dlib/january03/smith/01smith.html

Thomas, Chuck, and Robert H. McDonald. 2007. “Measuring and Comparing Participation Patterns in Digital Repositories.” D-Lib Magazine 13 (9/10). Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september07/mcdonald/09mcdonald.html

Thomas, Sarah E. 2006. “Publishing Solutions for Contemporary Scholars: The Library as Innovator and Partner.” Library Hi Tech 24 (4): 563–573.

Troll Covey, Denise. 2007. “Faculty Rights and Other Scholarly Communication Practices.” Digital Libraries Colloquium, January 17, 2007, Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://www.library.cmu.edu/People/troll/FacultyStudy_DL_Colloquium.ppt

Walters, Tyler O. 2007. “Reinventing the Library: How Repositories Are Causing Librarians to Rethink Their Professional Roles.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 7 (2): 213–225.

Waters, Donald. 2008. “Open Access Publishing and the Emerging Infrastructure for 21st-Century Scholarship.” Journal of Electronic Publishing 11 (1). Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3336451.0011.106

Williams, Robin, and David Edge. 1996. “What is the Social Shaping of Technology?” Research Policy 25 (6): 856–899. Retrieved April 12, 2008, from http://www.rcss.ed.ac.uk/technology/SSTRP.html

Williams, Susan P., and Fides Datu Lawton. 2005. “eScholarship as Socio-Technical Change: Theory, Practice and Praxis.” 3rd International Evidence Based Librarianship Conference, 16–19 October 2005, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Retrieved April 20, 2008, from http://conferences.alia.org.au/ebl2005/Williams.pdf

Wilson, Melanie, and Debra Howcroft. 2000. “The Politics of IS Evaluation: A Social Shaping Perspective. Proceedings of the Twenty-first International Conference on Information Systems, 94–103. Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Retrieved October 7, 2008, from http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=359640.359727

Winner, L. 1985. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” In Donald MacKenzie and Judy Wajcman, eds., The Social Shaping of Technology: How the Refrigerator Got Its Hum, 26–38. Milton Keynes; Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Notes

Within the context of this paper, IR is referenced interchangeably as a technology, a system, and an information and communication technology. IR represents a category of technologies (such as word processing or database management) and there is a range of free and commercial software to implement IRs, including DSpace, which will be described later in this paper.

The interviews and observations in regard to scholarly communication patterns of scholars were held during academic year 2007/2008 in support of my doctoral work. The faculty members mainly represented humanities and sciences, but included a small representation of social sciences. Many of the faculty members were involved in interdisciplinary collaborations, some involving distributed work.

To demonstrate the impact of context on technology adoption, adaptive structuration theory introduces an appropriation process in which a technology is constituted differently by specific groups based on their needs and perceptions (Jackson, Poole, & Kuhn, 2002). Dourish (2003) further expands the appropriation concept to include reconfiguration, repurposing, incorporation, and customization of a technology to communicate its meaning within a community of practice.

Since its inception in 1991 as an e-print service for the high-energy physics community, arXiv (http://arXiv.org/) has successfully expanded its coverage in the fields of physics, mathematics, non-linear science, computer science, quantitative biology, and statistics. It is a collaboration between the Cornell University Library and Cornell's Information Science Program.

Several important groups, such as the open access community, higher education administrators, non-users, and the anti-open access group, are not included in the analysis. Also, each relevant group could be analyzed in categories, as no group is homogeneous. For instance, there is a range of capabilities and interests represented by research institutions based on their funding models, mandates, and technical capabilities. From a theoretical standpoint, a complete social construction analysis of IR should make an effort to include all the relevant social groups (and their heterogeneity), as such information may reveal unexpected facts.

For example, a faculty member with an administrative role in a scholarly society might use an IR to make available the society’s proceedings, which were previously available in print format only or were available through an arrangement with a commercial publisher.

The DSpace repository architecture and application was jointly developed by the MIT Libraries and Hewlett-Packard during 1999-2002. As one of the first IR applications, DSpace played a significant role in promoting the role of IRs as an open source institutional repository for digital materials created and managed by cultural and educational institutions.

A reverse salient is a weak link in any system that impedes progress. The technology historian Thomas P. Hughes introduced the phrase to refer to components in the system that have fallen behind or are out of phase with the others.

The imbalance denotes the gap between rapidly increasing subscription fees and limited library acquisition budgets. It also indicates the time lag between authorship, peer review, publication, and dissemination, as well as the imbalance of authorship and ownership of copyrights (Association of Research Libraries, 1998). For example, authors may often need to seek permission from their publishers to republish or share their materials for other research purposes (other than those arrangements supported by fair use guidelines).

In 2006, Denise Troll Covey interviewed 87 faculty members at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) about their practices and understanding of electronic publishing and dissemination. Only 16% of the faculty interviewed knew the meaning of the phrase “open access” and 3% were interested in their right to self-archive their publications. She concluded that most of the faculty interviewed were not as concerned as library administrators about the economic crisis in scholarly communication. They did not seem to perceive the impact that the economic crisis is having on access to their work and were more concerned about promotion, tenure, and the "legacy" of their publications.

They employed a work-practice study based on traditional anthropological participation observation. Reflecting the results of their study, they modified the default DSpace interface to accommodate the users’ preference for disciplinary practices (rather than institutional) and also factored in their need for customized and contextual tools.

Supported by the Cambridge and MIT Libraries, Pablo Boczkowski (Department of Communication Studies, Northeastern University) conducted a study to explore the cultural and political dynamics in the adoption of institutional repositories. The findings reported in this paper are based on my conversations with him in addition to my notes from his September 2006 presentation at a meeting at Cambridge, UK. Boczkowski has not published the findings yet.

For instance, both Bohlin (2004) and Fjällbrant (1997) apply social construction of technology theory to areas of scholarly communication that are in transition. Bohlin’s case study is based on arXiv (arxiv.org); he evaluates the adoption process of this eprint archive by scholars. Fjällbrant’s case study involves the role of journal articles in scholarly conduct and how the journal article became the main currency of scholarly communication.

“Black box” in actor-network theory represents stabilized networks. For instance, the actors in the traditional publishing system have established and clear roles. The publishing process has been well defined and has been stable for quite some time.

Australian Research Repositories Online to the World (ARROW) aims to develop and test a national resource discovery service and support best practices for institutional digital repositories in Australia.

ANT’s problematization and translation defines the means by which supporters of a technology enroll and exclude dissenters in order to make technology a success (Wilson & Howcroft, 2000).

Bijker’s (1995) introduction of the technological frame concept (including power as a way of framing) is important for explaining how the social environment constrains and structures an artifact’s design. However, he characterizes technological frames as common characteristics within actors, not as institutional attributes. Power and economic strength are also used in describing relevant groups in more detail (Bijker, 1995). Semiotic power is fixed and represented in technical frames such as the publishers’ established role in accreditation. Micropolitical power is manifested in interactions of relevant social groups and involves access to funds, control over standards, and policy oversight.

Social constructivist approaches advocate a principle of methodological symmetry to indicate that the researcher maintains methodological neutrality because he or she does not evaluate any of the knowledge claims made by different social groups about the properties of the technology under study.

Gidden’s (1984) structuration theory is defined as the production and reproduction of social systems by members’ use of resources and rules that guide their interactions. It posits a duality of structure to emphasize that human action simultaneously creates structures of social systems and is shaped by such structures.

PubMed Central is a free and unrestricted institutional repository maintained by the National Institute of Health by the National Library of Medicine. It focuses on biomedical and life sciences journal literature.