"A living, creeping lie": Abraham Lincoln on Popular Sovereignty

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): Copyright © Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. For permission to reuse journal material, please contact the University of Illinois Press (UIP-RIGHTS@uillinois.edu). Permission to reproduce and distribute journal material for academic courses and/or coursepacks may be obtained from the Copyright Clearance Center (www.copyright.com).

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

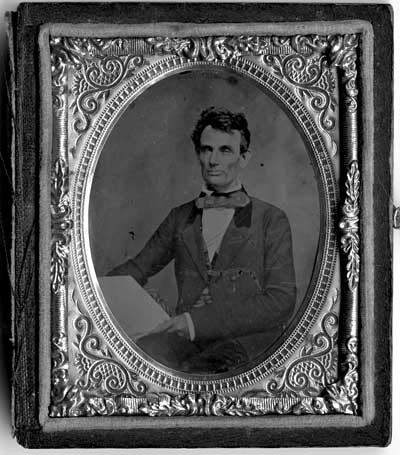

Debating Stephen A. Douglas in 1858, Abraham Lincoln dismissed Bleeding Kansas's importance: "If Kansas should sink to-day, and leave a great vacant space in the earth's surface, this vexed question [of slavery] would still be among us."[1] The two men were contending for the Illinois senate seat that Douglas then occupied. Lincoln was a corporate lawyer, not very well known outside Illinois and stifled in his political career because he had been a Whig (until 1856) in a Democratic state. If elected senator, his political career would be greatly advanced. Douglas, by contrast, had long been a power in the Democratic party, a likely candidate for president, and one of the most prominent of the Young Americans—the expansionist politicians of the antebellum era. The senatorial election was crucial for both men. While Lincoln sought to resuscitate long-dormant political ambitions, Douglas sought to prevent the end of his political career and hopes for the presidency.[2]

Both men owed much of their political circumstances to Bleeding Kansas. Douglas had lost popularity when his controversial 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act alienated Northerners. Political turmoil and violence, which earned the territory its nickname, eroded Democratic party power. Then, in 1857 and 1858, Douglas lost southern support by opposing a proslavery constitution for Kansas. The very events in Kansas that hurt Douglas's career helped Lincoln's.

Biographers have long recognized the importance of Bleeding Kansas in Lincoln's rise to power. [3] But Lincoln dismissed the actual events in Kansas as less important than their context—specifically, the "vexed question" of slavery and Senator Douglas's flawed solution to that question—popular sovereignty. Lincoln viewed popular sovereignty, the underpinning philosophy of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, much as Douglas did—as rooted in the principles of the republic. Douglas saw it as the great principle inherent in democracy. Lincoln, however, viewed it as a pernicious subversion of true republicanism. While Republicans such as William Seward, Charles Robinson, and Charles Sumner attacked Douglas for the results of popular sovereignty, especially the chaos of Bleeding Kansas, Lincoln struck at its meaning. By arguing over whether popular sovereignty worked, Republicans in Congress and in Kansas implicitly conceded popular sovereignty's legitimacy as political doctrine. By striking at popular sovereignty's meaning, Lincoln denied Douglas's great principle that legitimacy.

In 1854 United States politics were in equilibrium. The "vexed question" of slavery, as Lincoln would call it, had been resolved by the Compromise of 1850. That congressional agreement settled the status of slavery in the territories acquired from Mexico. Along with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had divided the Louisiana Purchase between slave and free territories, the 1850 Compromise meant that all the territories were either designated as open to slavery or not. Lincoln was willing to accept the Compromise, including the Fugitive Slave Law that so angered many Northerners. He thought it his "duty" to uphold the law and constitutional obligations to slavery, including the return of fugitives. To his old friend Kentuckian Joshua F. Speed, Lincoln wrote, "I also acknowledge your rights and my obligations, under the constitution, in regard to your slaves. I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils; but I bite my lip and keep quiet." Lincoln later said that the Compromise of 1850 had silenced "'forever'" the slavery controversy. Politicians such as Lincoln spoke of "finality" on the slavery issue after 1850.[4]

What became Kansas Territory lay in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase, territory closed to slavery under the Missouri Compromise. The expansionist-minded Douglas eagerly sought to organize that territory, but several attempts to do so had failed. Southern politicians simply had no interest in organizing territory that would become free states and add further votes to the free-state bloc in Congress. In return for southern votes to organize Kansas Territory, Douglas traded away the Missouri Compromise's exclusion of slavery. Instead, Kansas and Nebraska territories would be organized with no restriction on slavery under the formula called popular sovereignty. Douglas claimed that this was simply democracy at its best: "let the people decide." Many northerners, however, were shocked and angered by the Kansas-Nebraska bill. "The Appeal of the Independent Democrats" called the Kansas-Nebraska bill "a gross violation of a sacred pledge" that the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase would be "consecrated to freedom." Now, that "vast unoccupied region" would be closed to immigrants from the free states and abroad and "convert[ed] into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves."[5]

One result of the furor over Kansas-Nebraska was the emergence of the Republican party—a coalition of old Whigs, anti-immigrant Know Nothings, and Democrats disaffected from their party by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Lincoln, as a long-time Whig, was relatively slow to join the new party in Illinois. In August 1855 he wrote to his old friend Speed that his party affiliation was "a disputed point. I think I am a whig; but others say there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist." Reluctant to be "unwhig[ged]," Lincoln concluded, "I now do no more than oppose the extension of slavery." Not until 1856 would that position make him officially a Republican.

Lincoln's loyalty to the Whig party had left his political career in Illinois moribund. He had served in the state legislature where Whigs were a minority and in the U.S. Congress for one term where he was the only Whig from the state of Illinois. As biographer David Herbert Donald writes, "Illinois offered no future for an ambitious Whig politician. He recognized that his public career was at an end." He had important clients such as the Illinois Central Railroad, but he was "frustrated and unhappy with a political career that seemed to be going nowhere."

After the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed Congress, he emerged as a prominent voice against Douglas's popular sovereignty. Lincoln spoke at Springfield while Douglas was appearing there for the state fair. The speech made such an impression that Lincoln repeated it at Peoria a couple weeks later. For the next six years, as a senatorial and later presidential candidate, Lincoln built an elaborate critique of popular sovereignty in numerous speeches throughout the country. [6]

Critics such as Lerone Bennett Jr. assert that the Kansas-Nebraska Act "made it possible for Lincoln to revive a political career that was in terminal arrest" and created the "new phenomenon" of "the antislavery Abraham Lincoln." Whereas Lincoln's previous political career had been as an advocate of the Whig's economic program—the American system—Lincoln now turned his attention to the slavery issue. [7] Bennett's cynicism may be a useful corrective to what William Lee Miller describes as the reluctance of many to accept Lincoln as a practicing and partisan politician. They prefer to see him as transformed from the "mere politician" to "The Greatest Man in the World." The transformation occurred, says Miller, "when the Kansas-Nebraska Act provoked him to make opposition to slavery his central purpose, and so saw him suddenly lifted up from having been an ordinary politician, dealing with legislative committees and party calculations, with rivers and harbors and quorum calls and appeals to the German vote, to become instead a transcendent moral hero dealing with liberty, equality, and union."[8]

Don Fehrenbacher wisely observed that both belief and ambition motivated Lincoln: "Since a man often has more than one reason for what he does, the depth and sincerity of Lincoln's conviction can be affirmed without the slightest discounting of his intense, sleeping ambition." Richard Carwardine sees Lincoln as "more serious and morally engaged" after the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Peoria speech was Lincoln's first on the slavery issue, although he had dealt with the issue in and out of Congress. Lincoln, in autobiographical sketches that he composed for the 1860 presidential campaign, wrote that he "was losing interest in politics" and "his profession had almost superseded the thought of politics in his mind" "when the repeal of the Missouri compromise aroused him as he had never been before." [9]

Miller considers it an act of "considerable moral courage" for Lincoln to challenge Douglas: "Senator Douglas was one of the most powerful and famous men in the land.... He was a practiced, powerful debater, full of energy, articulate, sarcastic, scathing, formidable." Lincoln, however, was "Approximately nothing. A one-term former congressman, now a private citizen." Lincoln himself noted in the mid-1850s, "Twenty-two years ago Judge Douglas and I first became acquainted. We were both young then.... Even then, we were both ambitious.... With me, the race of ambition has been a failure—a flat failure; with him it has been one of splendid success. His name fills the nation...." Lincoln made the challenge because he was genuinely horrified at popular sovereignty. He wrote to Illinois politician John M. Palmer, "You know how anxious I am that this Nebraska measure shall be rebuked and condemned every where." [10] The irony of Lincoln's opposition to popular sovereignty is that his arguments against Douglas's doctrine seemed to accept Douglas's premise that popular sovereignty spoke to the central nature of republican self-government. In that, Lincoln's opposition to popular sovereignty differed from the anti-popular-sovereignty arguments of other Republicans that emphasized the practical workings of popular sovereignty, specifically the events of Bleeding Kansas. By concentrating on popular sovereignty's practical effects, however, these Republicans seemingly accepted the doctrine as legitimate republicanism. By attacking Douglas on popular sovereignty's own ground of principle, however, Lincoln challenged Douglas's assertion that popular sovereignty was merely self-government at work.

Douglas and Lincoln knew that the debate was about principle. They even agreed on the principle involved: the nature of republican government. Douglas believed that popular sovereignty—the ability of white men to decide whether to have slavery within their political jurisdiction—was the chief tenet of republican self-government. Lincoln agreed that the fundamental principles of a republic were at stake. But he believed that Douglas's popular sovereignty was, in fact, dangerous because it neglected the immorality of slavery, which while it must be constitutionally tolerated, was nonetheless corrosive of republican ideals. Lincoln objected that popular sovereignty equated freedom with slavery. Douglas repeatedly said that he did not care which triumphed as long as the people got to decide. Lincoln cared. He believed that slavery was wrong and freedom right. He believed that the Founders had set a moral stigma upon slavery that popular sovereignty removed, making it easier to justify the extension of slavery. Speaking at Bloomington, Illinois, in the fall of 1854, Lincoln agreed that leaving men to govern their own affairs was "morally right and politically wise" but irrelevant to the slavery issue because slavery was "a moral, social, and political evil." [11]

Lincoln's October 1854 speech at Peoria would be, perhaps, his most ringing condemnation of popular sovereignty. Carwardine says that the speech "contained most of the essential elements of his public addresses over the next six years." At Peoria, Lincoln deplored the Kansas-Nebraska Act for resuscitating, not calming, slavery agitation. He avowed suspicions that popular sovereignty really intended to spread slavery. He condemned slavery as both a "monstrous injustice" and a betrayal of "our republican example." He asserted that if blacks are men, which he considered self-evident, they were entitled to equality under the Declaration of Independence. He denied that "there can be MORAL RIGHT in the enslaving of one man by another." Douglas drew legitimacy for popular sovereignty from the supremacy of self-government in the ideology of nineteenth-century Americans. Lincoln, seeking to deny that self-government applied in this case, turned to the prestige of the Revolutionary generation. "The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms, and the former is being rapidly displaced by the latter." [12]

Lincoln's approach to popular sovereignty contrasts with that of another prominent Republican, William H. Seward, senator from New York. Seward's speech on the Kansas-Nebraska bill—made during the congressional debates over its passage—is famous for its ringing challenge to the Slave Power. Seward is also notable because he became Lincoln's leading rival for the 1860 Republican nomination. His views, therefore, can be seen as important to mainstream Republican thought on popular sovereignty, making them worth comparing to Lincoln's. Seward's speech "Freedom and Public Faith" in February 1854, as well as his remarks in late May 1854 when the bill's passage seemed certain, constitute the senator's important statement of opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska bill, the equivalent of Lincoln's Peoria speech.

Both men began with historical overviews. Lincoln started with the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and continued to the passage of Kansas-Nebraska to show slavery's territorial expansion. Seward began even earlier, in 1763. Seward used history to show how the Kansas-Nebraska Act unsettled a long-standing policy of limiting slavery's expansion and overturned—"abrogated" was Seward's word—the Missouri Compromise's prohibition against slavery in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase. Seward also asserted that popular sovereignty was inferior to congressional direction of the territories. The flaw of popular sovereignty was that it equated "Free institutions and slave institutions," a point similar to Lincoln's. But Seward criticized the frontiersman's fitness to make the decision. Kansas-Nebraska made "the interested cupidity of the pioneer ... a wise arbiter, and his judgment an earlier safeguard, than the collective wisdom of the American people and the most solemn and time-honored statute of the American Congress."

Seward dealt with many of the practical effects of Douglas's legislation on Indian policy, other territories such as Oregon and Washington, and the national debate over slavery. He concluded with the conviction that "equal and universal liberty of all men" would triumph, but his larger concern was to assert the principle of congressional control over slavery in the territories that Douglas's popular sovereignty denied. In late May 1854, with the passage of the bill inevitable, Seward once again spoke. It was in those remarks that Seward first asserted that slavery was a moral issue. While the slave states "maintain that African slavery is not erroneous, not unjust, not inconsistent with the advancing cause of human nature.... we of the free States regard slavery as erroneous, unjust, oppressive, and therefore absolutely inconsistent with the principles of the American Constitution and Government." But Seward passed over that quickly and spent more time on the balance of political power between free and slave states that Kansas-Nebraska threatened to unsettle. Once again he reviewed the abrogation of the Missouri Compromise and warned the south that this would render future compromises impossible. The May remarks are most famous for Seward's boast that foreign immigration would allow the north to control the territory: "Come on, then, gentlemen of the Slave States. Since there is no escaping your challenge, I accept it in behalf of the cause of freedom. We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers as it is in right."[13] But Seward's focus was less on popular sovereignty's principles than on "public faith"—that popular sovereignty had overturned a settled agreement about slavery.

Although Lincoln's Peoria speech dealt with many of the themes Seward raised, he early announced to the audience that he would be dealing with principle. He promised to show that Kansas-Nebraska's repeal of the Missouri Compromise was wrong: "wrong in its direct effect, letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska—and wrong in its prospective principle, allowing it to spread to every other part of the wide world, where men can be found inclined to take it." Much more directly than Seward, Lincoln denounced popular sovereignty's "declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery." "I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites." Lincoln recognized that Douglas had set out a principle of his own with the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. When Seward discussed the abrogation of the Missouri Compromise, he did so to argue that it was not legally possible to abrogate such an agreement and, when that failed, to show the dangers of undoing settled sectional agreements. Lincoln also denied that the 1850 compromise overturned that of 1820 and accused the South of bad faith, but he specifically argued that the repeal was wrong because its principle was wrong. First, the principle of popular sovereignty insisted that all members of the union ought to be able to take their property to the territories. That only made sense if there was no difference between northern livestock and southern slaves, but Lincoln refused "to deny the humanity of the negro." He further asserted that southerners recognized that humanity, as evidenced by their dislike of the slave-dealer and the existence of a free black population. Lincoln then dealt with Kansas-Nebraska's avowal of "the sacred right of self government." Again, Lincoln asserted that slavery violated self government. "When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism." Although Lincoln famously hedged by denying he believed in "political and social equality between whites and blacks," he did assert that African Americans were "men" under the meaning of the Declaration of Independence and that Douglas's popular sovereignty thus violated republican self-government.[14]

Only in one passage did Lincoln deal with the mechanics of popular sovereignty. He faulted the legislation for not specifying how the voters would decide. "Some yankees, in the east, are sending emigrants to Nebraska, to exclude slavery from it; and, so far as I can judge, they expect the question to be decided by voting, in some way or other. But the Missourians are awake too. They are within a stone's throw of the contested ground. They hold meetings, and pass resolutions, in which not the slightest allusion to voting is made. They resolve that slavery already exists in the territory; that more shall go there; that they, remaining in Missouri will protect it; and that abolitionists shall be hung, or driven away. Through all this, bowie-knives and six-shooters are seen plainly enough; but never a glimpse of the ballot-box."[15]

More importantly, however, Lincoln emphasized slavery's immorality and the incompatibility between slavery and republicanism. "I particularly object to the NEW position which the avowed principle of this Nebraska law gives to slavery in the body politic. I object to it because it assumes that there can be MORAL RIGHT in the enslaving of one man by another." That contradicted the "fathers of the republic" who marked slavery as wrong and only tolerated it out of "Necessity." The Founders "began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for SOME men to enslave OTHERS is a 'sacred right of self-government.'" Lincoln considered these principles not just contradictory but incompatible. "In our greedy chase to make profit of the negro," he warned, "let us beware, lest we 'cancel and tear to pieces' even the white man's charter of freedom." Lincoln called on Americans to "turn slavery from its claims of 'moral right,' back upon its existing legal rights, and its arguments of 'necessity.'" Doing so would repurify the nation's republican principles. Like Seward, Lincoln pointed out the danger of renewing sectional agitation, but less for political reasons than for moral ones. He reiterated that legislation could not convince people that slavery was right. [16]

Despite Lincoln's emphasis on principle, Seward's challenge set the stage for Republicans to concentrate on events in Kansas. Those events were indeed tempestuous. Missourians crossed the border and voted in territorial elections. The territorial legislature thus elected passed a slave code. When free-state settlers protested by forming an extra-legal government of their own, and when territorial and federal forces attempted to suppress that free-state movement, Republicans found material with which to indict the Democratic party and popular sovereignty. In so doing, however, free-staters in Kansas Territory and national Republican politicians sometimes lost sight of popular sovereignty's principles. They became so intent on reciting what had gone wrong in the territory that their critique of popular sovereignty turned on its workings rather than on its flawed interpretation of republican government.

On July 4, 1855, Charles Robinson, a New England settler and a leader of the free-state movement, gave the holiday oration at a grove outside Lawrence, Kansas. Lawrence was the leading New England settlement in the territory, although the free-state movement consisted not just of New Englanders, but of midwestern settlers and even some Missourians who wished to see Kansas become a free state. One of Robinson's rivals for leadership in the free-state movement was James H. Lane, a former Indiana Democratic politician who had voted for the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The fraudulent voting in territorial elections, however, convinced Lane that popular sovereignty was a fraud. Lane appealed to the racism of many settlers. Although he would later work for black rights during the Civil War, he had famously declared upon settling in Kansas that "he would as soon buy a negro as a mule." [17] It was within this context that Robinson spoke. Kansas settlers were being radicalized by what they saw as infringements of their rights at the polls, but they were not abolitionists.

Robinson began his speech with the obligatory historical overview. But his point was to contrast the colonial development of Massachusetts and Virginia. Modern historians might not give Robinson high marks for accuracy, for he maintained that colonial Virginia had been settled easily with little suffering while the Puritan settlers had endured greater hardships. He then launched into an argument about the superiority of free labor to slave labor. He declared that the population, value of property, amount of manufacturing, and productivity of agriculture was greater in free states than in slave. Robinson made a point of drawing his information from southern, rather than northern or abolition, sources. In fact, his entire argument against slavery was practical and economic rather than moral. Throughout the oration, Robinson was careful to show more concern for slavery's effects on whites than on blacks. He justified this by saying that since slavery was being imposed on Kansas settlers, it was necessary to judge what its effects were. Two-thirds of the way through the oration, Robinson assessed the plight of those Kansas settlers. "Who are we? Are we not free-born? Were not our mothers, as well as fathers, of Anglo-Saxon blood?" By emphasizing the settlers' racial heritage, with mothers of Anglo-Saxon blood, Robinson distinguished his audience from black slaves whose servile status derived from their mothers. He went on to ask, "What are we? Subjects, slaves of Missouri. We come to the celebration of this anniversary with our chains clanking about our limbs.... We must not only see black slavery, the blight and curse of any people, planted in our midst, and against our wishes, but we must become slaves ourselves." Robinson then quoted at length from southern publications asserting that dissent against slavery would not be tolerated in Kansas. Only after he had established the link between advocating slavery and its effects—economic, moral, and political—on whites, did Robinson inveigh against slavery's consequences for the black slave: its break up of the slave family, its denial of the equality of blacks, its theft of black labor, its "tyranny and oppression a thousand fold more severe than that which our ancestors rose in rebellion against." Yet when he did so, Robinson carefully avoided mentioning the race of the victims, and his examples of the cruelties of racial slavery were closely followed by examples of how white Kansans were enslaved by Missourians, thereby eliding the distinction between the two groups. Robinson made his hearers just as much the victims of race slavery as were the black slaves. Robinson hinted at abolitionism in his suggestion that, if self-rule for Kansas settlers required slavery to be abolished in Missouri, "then let that be the issue." [18]

While Robinson cleverly shaped a free-labor argument into one with subversive abolitionist potential, he never attacked popular sovereignty. Robinson and his followers had been, in fact, the ones to take up Seward's challenge to populate the territory. They did not object to the principle of popular sovereignty—letting the settlers decide. Instead, they objected that the Missourians had not followed that principle. Instead, Missouri "border ruffians" had trampled the rights of white settlers at the ballot box and were imposing slavery against the settlers' will in violation of Kansas-Nebraska's promise.

A year later, the situation in the territory had deteriorated even further. President Franklin Pierce had called Robinson and the free-staters "traitors." Clashes between proslavery and free-state settlers had led to an armed stand-off at Lawrence in the winter of 1855. Violence would indeed break out during the following summer of Bleeding Kansas. One of the events that helped to stimulate that violence was Representative Preston Brooks's attack on Senator Charles Sumner. In a Senate speech on Kansas, Sumner made insulting reference to the congressman's uncle, South Carolina Senator Andrew P. Butler, thus angering Brooks. Sumner's speech laid out the "Crime" that Democrats and the proslavery party had committed against Kansas Territory. More powerfully than any other speaker, Sumner condemned slavery and defended abolitionists as fanatics for liberty. Sumner divided his speech into three parts: the crime, the apologies for it, and the remedy. The crime began with the Missouri Compromise and its repeal by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Sumner called popular sovereignty a "swindle" because it gave settlers no power to select their territorial officials, only power to choose slavery. Popular sovereignty was a mere conspiracy to introduce slavery, but the conspiracy went awry when an unexpected number of northern settlers moved to Kansas. Proslavery men thus turned to invading Kansas at election time to secure their will. Sumner detailed the history of Kansas elections, of attacks on antislavery men on the Kansas/Missouri border, of the threat against Lawrence the previous winter, and of the "usurpation" and draconian rule imposed by the fraudulently elected proslavery territorial legislature. Echoing Robinson's rhetoric, Sumner said, "Slavery now stands erect, clanking its chains on the Territory of Kansas." [19]

Sumner found that four apologies were made to excuse events in Kansas. The "Apology Tyrannical" held that since the first territorial governor had certified the election of the territorial legislature, the proceedings were legal and the complaints invalid. Sumner rejected that apology as despotism acting under the guise of law. Just as the British had once denied colonial freedoms by arguing that the Americans were technically represented in Parliament, so Congress denied Kansans redress against fraud by pointing to the governor's acceptance of the returns. The "Apology Imbecile" maintained that the president lacked power to act. Sumner believed that when the interests of the Slave Power were served, no one saw problems with presidential action. The "Apology Absurd" excused the actions of the proslavery men by pointing to those of alleged secret free-state societies. Finally, the "Apology Infamous" blamed the New England Emigrant Aid Company for violence in the territory. Sumner's defense of the Emigrant Aid Company invoked rhetoric similar to Robinson's. Like Robinson, Sumner warned about the danger of white enslavement and upheld the superiority of free labor over slave. If northerners failed to migrate, as they had a right to do, "they would be fit only for slaves themselves." Later in his speech, Sumner expanded the free-labor comparison by contrasting Lawrence, Kansas, with Butler's South Carolina. Sumner's remedy was to admit Kansas as a free state under the constitution that Robinson, Lane, and their followers had drafted. In order to show a precedent for the free staters' request for statehood, Sumner discussed the case of Michigan, which he maintained exactly modeled the process that Kansas free-staters were following. Congress did not admit Kansas in 1856. Instead, it adhered to a policy closer to what Sumner called the remedies of "Tyranny" and "Injustice." The former meant forcing Kansas free-staters to obey territorial law. The latter, offered by Stephen Douglas, was to call for a constitutional convention when the population reached the level that entitled a state to one representative in Congress.[20]

Like Robinson, Sumner obscured the line between black slavery, which he eloquently condemned, and white. He appealed to "Christian sympathy with the slave," but included it with the need to defend free labor, the principles of the American Revolution, and "fellow-citizens, now subjugated to a tyrannical Usurpation." "What are trial by jury, habeas corpus, the ballot-box, the right of petition, the liberty of Kansas, your liberty, sir, or mine," Sumner asked, "to one who lends himself.... [to] that preposterous wrong which denies even the right of a man to himself! Such a cause can be maintained only by a practical subversion of all rights."[21] Here Sumner's condemnation of events in Kansas, like Robinson's before it, made Lincoln's point that slavery endangered white liberty. But Sumner and Robinson made their argument by pointing to what had happened with popular sovereignty in Kansas. Lincoln barely touched on actual events. Rather, for Lincoln it was the principle of popular sovereignty—the equation of slavery with freedom—that threatened liberty. Like Robinson, Sumner did not condemn the principle of popular sovereignty. The force of his detailed explication of the "Crime against Kansas" was to keep attention on the workings, rather than the philosophy, of popular sovereignty.

When Lincoln did address specific events in Kansas, he used them to indict popular sovereignty generally. In a speech at Springfield in 1857, he answered Douglas's objections that free-staters in Kansas had failed to vote in the selection of constitutional convention delegates. Faulting the registration system, Lincoln pointed out that since few free-staters had been registered, they were boycotting the election. Then Lincoln noted that the returns of that election indicated that only about "one sixth of the registered voters, have really voted; and this too, when not more, perhaps than one half of the rightful voters have been registered, thus showing the thing to have been altogether the most exquisite farce ever enacted."[22]

Interestingly, Lincoln's most extensive comments on events in Kansas came in a private letter to Speed. The letter reveals that Lincoln was knowledgeable on Kansas affairs, as any newspaper reader of the 1850s must have been. He referred to voting fraud, to "Poor Reeder" (the first territorial governor), to the enactments of the territorial legislature, and to Missourians "Stringfellow & Co." Those details tended to be absent from his public pronouncements. Further evidence that Lincoln knew of events in Kansas comes from his membership on the National Kansas Committee, which distributed cash, arms, clothing, and provisions to free-state settlers in 1856, and from his correspondence with W.F.M. Arny, the committee's secretary, and with Mark Delahay, a free-state newspaperman. But he professed no surprise (as Speed apparently did) at the fraud and illegitimate proslavery supremacy in Kansas, for he felt that the law was "being executed in the precise way which was intended from the first." [23] For Lincoln it was not that popular sovereignty had been badly implemented in Kansas, resulting in fraud and violence; instead, Lincoln viewed popular sovereignty as fundamentally flawed in its very conception.

Lincoln did follow the twists and turns of events in Kansas for their impact on his political opportunities. Although his efforts to win an Illinois senate seat failed in 1855, he was actively campaigning for the one that would be available in 1858: Douglas's. Douglas was vulnerable not only because of the controversy caused by his Kansas-Nebraska Act, but also because of the crisis over the Lecompton Constitution. Congress had followed Douglas's policy of calling for a constitutional convention. Because free-state voters, fearing fraud, had boycotted the election of constitutional convention delegates, the Lecompton convention produced a solidly proslavery constitution at a time when the territory's settlers were predominantly free-state. Precisely because they knew the settlers to be favorable to the free-state party, the Lecompton delegates did not submit the constitution for an up-or-down ratification vote. Instead, the territory's voters could select Lecompton "with" or "without" slavery. Lecompton "with" slavery meant that Kansas would be a slave state. Lecompton "without" slavery, however, only forbade further slave importations while allowing those slaveowners in the territory to continue holding their human property. In 1857 Kansas asked for admission to the Union as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution. Free-state settlers protested that Lecompton violated popular sovereignty's promise of a chance to reject slavery entirely. Nonetheless President James Buchanan, under heavy southern pressure, supported Lecompton and presented it to Congress.[24]

Douglas opposed Lecompton even though it cost him political support among white Southerners. He could not reconcile the constitution with popular sovereignty's majoritarian rationale. Furthermore, he knew it would cost him dearly in Illinois. So Douglas chose to defy the Buchanan administration and join Republicans in opposing Lecompton. He even opposed the face-saving English Compromise, a Democratic measure that returned the constitution to Kansas for another ratification vote in which free-staters participated and finally voted Lecompton down. As a result of Douglas's stand, Buchanan worked to undermine the senator's re-election chances, and Republicans, much to Lincoln's horror, embraced Stephen A. Douglas. The issue of who got credit for defeating Lecompton was important enough that Lincoln was at pains to demonstrate that Republicans had furnished more votes to defeat Lecompton than had Douglas, twenty to three by Lincoln's count. Eastern Republicans, such as editor Horace Greeley, even suggested that Illinois Republicans should support Douglas's re-election. Illinois Republicans, however, had no such intention. Their enmity with Douglas was too long-standing and too embittered to make Douglas acceptable, nor was Douglas interested in converting to the Republican Party. In fact, Douglas would write his 1859 exposition on popular sovereignty for Harper's in part to fend off Republican encroachments on popular sovereignty and to reassert it as Democratic Party doctrine. The Republican state convention thus nominated Lincoln as "the first and only choice of the Republicans of Illinois for the United States Senate." For Republicans, accepting Douglas as the candidate would have meant accepting popular sovereignty. Since by 1858, free-staters had finally captured control of the Kansas territorial legislature, popular sovereignty's immediate danger had receded. Lincoln needed to highlight popular sovereignty's continued threat to the republic despite Kansas's relative calm. [25]

As a senatorial candidate in 1858, Lincoln fought Douglas on ground of the incumbent senator's own choosing: the legitimacy of popular sovereignty as a republican principle. Lincoln's acceptance came in the famous "House Divided" speech. By the time Lincoln spoke, both antislavery and proslavery writers had used the metaphor of the house divided to argue that the United States could not be both free and slave. [26] One premise of Douglas's popular sovereignty, of course, was that it could be both. Lincoln not only rejected that premise, he questioned Douglas's sincerity in asserting it, arguing that Douglas really intended to nationalize slavery. In the opening of the campaign, Lincoln pointed out that until the Kansas-Nebraska Act, slavery had been excluded from most of the territories. Douglas's legislation "opened all the national territory to slavery." Although the Kansas-Nebraska Act left settlers "perfectly free," "subject only to the Constitution" to choose whether to have slavery, that choice was then followed by the Supreme Court's decision in the Dred Scott case, which said that congressional exclusions of slavery from the territories were unconstitutional and thus "declare[d] the perfect freedom of the people to be just no freedom at all." Lincoln saw Kansas-Nebraska and Dred Scott as part of a coordinated conspiracy: "We cannot absolutely know that all these exact adaptations are the result of preconcert." But when one sees a house being built with timbers prepared beforehand by "different workmen—Stephen [Douglas], Franklin [Pierce], Roger [Taney] and James [Buchanan].... we find it impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin and Roger and James all understood one another from the beginning, and all worked upon a common plan or draft before the first blow was struck." Lincoln predicted that a future Supreme Court decision might build on the timbers already laid by "declaring that the Constitution of the United States does not permit a State to exclude slavery from its limits." Lincoln repeated the charge of nationalization and conspiracy in the first debate at Ottawa. "Popular Sovereignty, as now applied to the question of slavery, does allow the people of a Territory to have slavery if they want to, but does not allow them not to have it if they do not want it."[27]

At the Charleston debate, Lincoln spent considerable time elaborating the theory that Douglas's Kansas policy was part of this effort to nationalize slavery. Douglas, of course, intended no such thing, but Lincoln biographer Donald believes Lincoln sincere in making the conspiracy charge, for belief in a "Slave Power" was prevalent in the north. At the Ottawa debate, when Douglas denied having discussed the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision with Chief Justice Taney or President Buchanan before it was issued, Lincoln rebounded by saying that did not disprove the existence of a conspiracy: "It can only show that he was used by conspirators, and was not a leader of them."[28] Lincoln's emphasis on a conspiracy to nationalize slavery was an elaboration of his argument that popular sovereignty threatened republican principles. Events in Kansas and the Dred Scott decision merely proved the assertions that Lincoln had been making since 1854.

Lincoln's famous Freeport questions addressed both Kansas's specific plight and the alleged conspiracy to nationalize slavery. In the first question, Lincoln asked if Douglas would support Kansas admission even if Kansas lacked the population specified in the English Compromise. Secondly, he asked Douglas if there was a way for a territory to prohibit slavery despite the Dred Scott decision. Thirdly, Lincoln wanted to know if Douglas would support a Supreme Court decision prohibiting states from excluding slavery. Finally, Lincoln asked if Douglas favored acquiring more territory—and in the 1850s that largely meant Latin American territory desired by southern filibusterers—that might reopen the slavery issue. [29]

Naturally, Lincoln found Douglas's replies unsatisfactory. Douglas claimed that if settlers failed to enact local police regulations to support slavery, it could not exist. This was Douglas's means of reconciling popular sovereignty with Dred Scott, which seemingly made it impossible to keep slavery out of the territories. Lincoln objected that the Dred Scott decision did not allow for Douglas's mechanism of local regulation, and that historically, in the colonial period, slavery had flourished even in the absence of supporting local laws. [30] In the debate at Quincy, Lincoln elaborated on Douglas's dilemma: "Judge Douglas has sung poans to his 'Popular Sovereignty' doctrine until his Supreme Court ... has squatted his Squatter Sovereignty out. But he will keep up this species of humbuggery about Squatter Sovereignty. He has at last invented this sort of do-nothing Sovereignty—that the people may exclude slavery by a sort of 'Sovereignty' that is exercised by doing nothing at all. Is not that running his Popular Sovereignty down awfully? Has it not got down as thin as the homœopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death?"[31]

During his debates with Douglas, Lincoln used details of Kansas's travails sparingly, as was his custom. At Charleston, he returned to the issue of whether popular sovereignty had brought the country closer to the end of slavery agitation, as Douglas claimed. Lincoln, of course, thought not. "Is Kansas in the Union? Has she formed a Constitution that she is likely to come in under? Is not the slavery agitation still an open question in that Territory?" Lincoln asked. It was at Charleston that Lincoln asserted, "If Kansas should sink to-day, and leave a great vacant space in the earth's surface, this vexed question would still be among us." Only by putting slavery on "the course of ultimate extinction" or by "surrender[ing]" to the nationalization of slavery could the agitation come to an end, according to Lincoln. [32] The particular details of Kansas events were less important than the larger principles demonstrated in Kansas's plight.

In the final debate at Alton, Lincoln used the specific example of what had happened in Kansas to indict Douglas's popular sovereignty. The "Nebraska policy," Lincoln told his audience, "was to clothe the people of the Territories with a superior degree of self-government, beyond what they had ever had before." But it had failed. He asked, "Have you ever heard or known of a people any where on earth who had as little to do, as, in the first instance of its use, the people of Kansas had with this same right of 'self-government?'" He concluded that popular sovereignty "has been nothing but a living, creeping lie from the time of its introduction till to-day."[33]

Although Republicans won the popular vote in the 1858 election, they did not win control of the state legislature that would elect the senator. Lincoln thus lost the senatorial race, another bitter disappointment. Afterwards, Lincoln wrote sadly, "I am glad I made the late race. It gave me a hearing on the great and durable question of the age, which I could have had in no other way; and though I now sink out of view, and shall be forgotten, I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I am gone." [34]

The loss nonetheless brought him national attention. After all, he had nearly unseated the powerful Douglas. In 1859 he continued campaigning against popular sovereignty and Douglas, refining his arguments. Lincoln feared that popular sovereignty's acceptance would strengthen slavery. He expanded his charge that popular sovereignty nationalized slavery, accusing it of paving the way "inevitably" for the reopening of the African slave trade: "Try a thousand years for a sound reason why congress shall not hinder the people of Kansas from having slaves, and when you have found it, it will be an equally good one why congress should not hinder the people of Georgia from importing slaves from Africa." In a speech in Columbus, Ohio, a few months later, Lincoln repeated the charge that popular sovereignty would lead to reopening of the slave trade. There he attacked the idea that "this insidious Douglas Popular Sovereignty" could be a way to oppose slavery "without straining our old party ties or ... being called negro worshippers." Lincoln argued that popular sovereignty instead led to "this gradual and steady debauching of public opinion, this course of preparation for the revival of the slave trade, for the territorial slave code, and the new Dred Scott decision that is to carry slavery into the free States."[35]

Lincoln expanded on the importance of public opinion in a speech at Cincinnati the next day. He accused Douglas of influencing northern public opinion so as to increase slavery's acceptance. First, Douglas refrained from condemning slavery as a "wrong." Secondly, he had implanted the notion that the Declaration of Independence's promise of equality did not apply to African Americans—a novel idea according to Lincoln—and one that denied blacks' common humanity. Thirdly, Douglas had said that in all conflicts between the black man and the crocodile, he favored the black man, but in all conflicts between the white man and the black, he favored the white man. The effects of this, Lincoln argued, was to create a logical "proposition" that "as the negro may rightfully treat the crocodile as a beast or reptile, so the white man may rightfully treat the negro as a beast or reptile." Douglas thus further dehumanized African Americans and thus legitimized their enslavement. [36]

Lincoln denied that popular sovereignty could create free states. Noting that "Douglas had sometimes said, that all the States that have become free, have become so on his great principle," Lincoln instead insisted that congressional prohibitions of slavery had been necessary to create free states. Lincoln defended the Ordinance of 1787 as the true source of the northwestern states' freedom. He noted that southern Ohio and northern Kentucky lacked the climatic or geographical differences often held to determine free soil and slave. He narrated the early histories of Indiana and Illinois to argue that, should slavery get a start, it would be impossible at the time of statehood to dislodge it. Of course, it was Republican Party policy that Congress had the power to prohibit slavery from the territories. The Dred Scott decision denied that such power existed, and Douglas insisted that popular sovereignty rendered it unnecessary. Speaking in Kansas, Lincoln used that territory's travails to illustrate his point. While the Northwest Territory reached free statehood "without any difficulty at all," Kansas Territory in the first application of popular sovereignty had suffered five years "of almost continual struggles, fire and bloodshed." "Kansas will come in as a free State, not because of popular sovereignty," Lincoln had earlier predicted, "but because the people of the North are making a strong effort in her behalf. But Kansas is not in yet. Popular sovereignty has not made a single free State in a run of seventy or eighty years."[37]

As late as 1859 Lincoln was reminding national Republicans of the danger of accepting popular sovereignty's principles. In general, he urged Republicans to look beyond local issues that might divide the party and to unite on common themes. New England Republicans should avoid nativism or trying to criminalize obedience to the Fugitive Slave Law. The Kansans had actually tried to work inside the framework of popular sovereignty, which they regarded as the best strategy for making Kansas a free state. Lincoln sought to remind them that the framework was itself fatally flawed. For Kansas Republicans, Lincoln had this advice: "Kansas, in her confidence that she can be saved to freedom on 'squatter sovereignty'—ought not to forget that to prevent the spread and nationalization of slavery is a national concern, and must be attended to by the nation." [38]

That year Lincoln traveled to Kansas where settlers had just written yet another constitution. Lincoln predicted, prematurely, that they would soon be a free state. He noted the uniqueness of Kansas's history: "Your Territory has had a marked history. There had been strife and bloodshed here." He blamed that strife on popular sovereignty: "The bloody code has grown out of the new policy in regard to the government of Territories." In a major speech at Leavenworth, Lincoln reminded Kansans that the territory's tumultuous events, which had so absorbed settlers' attention and energy, were comparatively trivial. Popular sovereignty had allowed the people to decide on slavery but not to select their own governors. This "could only be justified on the idea that the planting [of] a new State with slavery was a very small matter, and the election of Governor a very much greater matter." Lincoln pointed out that Kansans had had numerous territorial governors, but "although their doings, in their respective days, were of some little interest to you, it is doubtful whether you now, even remember the names of half of them. They are gone." The governor issue was trivial but the slavery issue was not. Lincoln argued, "If your first settlers had so far decided in favor of slavery, as to have got five thousand slaves planted on your soil, you could, by no moral possibility, have adopted a Free State Constitution." The owners would be too powerful politically and socially. Kansans, Lincoln predicted, would not know what to do with freedmen: they would not want to keep them "as underlings" or give them "social and political equality." Neither slave nor free states wanted an influx of free blacks, and sending them to Liberia would be prohibitively expensive.[39] Lincoln reminded his audience of why popular sovereignty was wrong: because it allowed the spread of a great moral evil that was well nigh impossible to eradicate once entrenched.

Just as Lincoln sought in 1859 to prevent creeping acceptance of popular sovereignty, he sought to prevent Republican acceptance of popular sovereignty's champion, Douglas. In early 1859, speaking at Chicago, Lincoln confronted head-on the belief that Republicans should have accepted Douglas as their candidate for the Senate. Although Republicans in other states had supported anti-Lecompton Douglas Democrats, Lincoln argued that backing Douglas would destroy the Republican Party. Lesser Douglas men might be absorbed by the Republicans but "Let the Republican party of Illinois dally with Judge Douglas ... they do not absorb him; he absorbs them." Douglas would claim their support as an endorsement for popular sovereignty, and Republican critiques of slavery as an evil would be lost. Later in the year, Lincoln spoke more generally of finding an acceptable presidential candidate. He warned against choosing someone who did not agree with Republican ideas "in regard to the prevention of the spread of slavery." Such a candidate would not win in the slave states and would also alienate Republican voters of "principle." [40] He seemed still worried that Republicans would be seduced into supporting Douglas.

Douglas and Lincoln continued to debate popular sovereignty even though the election of 1858 had concluded. Harold Holzer has called Douglas's 1859 article in Harper's Magazine and Lincoln's Cooper Union address of the following year the "final round of the Lincoln-Douglas debates." Douglas wrote both to defend popular sovereignty from the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision as well as to fend off Republican attacks. As Lincoln would later do at Cooper Union, Douglas grounded his exposition of popular sovereignty in historical sources such as The Federalist and the debates over the Constitution, and even sought help from historian George Bancroft. Lincoln would use some of the same sources. In keeping with rhetorical traditions of the period, Douglas sought to give popular sovereignty the pedigree of descent from the Founders. In part, Douglas accomplished this by defining the American Revolution as a struggle for local self-government within the empire. Douglas maintained that the local emphasis had continued under the Constitution. He construed the constitutional clause giving Congress authority over the territories to be limited strictly to land sales and not to government. Congress thus had no power to interfere in the "internal policy, either of the States or of the Territories." Therefore Congress could neither impose slavery nor prohibit it in either states or territories. Republicans, of course, believed that Congress could do so in the territories, but not in the states. As he had at Freeport, Douglas maintained that the Dred Scott decision did not change this fact. Dred Scott had correctly removed the Missouri Compromise prohibition, because such a prohibition was unconstitutional, but it had not, or so Douglas claimed, imposed slavery on the territories. Instead, Douglas contended that the only way in which the federal government could impose slavery on a territory was by enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law. Except for that instance, "slave property stands on the same footing [as other property] ... and in like manner is dependent upon the local authorities and laws for protection." In other words, on popular sovereignty. In his final section, Douglas reviewed the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act to show that they were "in perfect harmony with ... the principles" dividing federal and local authority. "The principle," Douglas concluded, "under our political system, is that every distinct political Community ... is entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities of self-government in respect to their local concerns and internal polity, subject only to the Constitution of the United States." [41]

Lincoln dismissed Douglas's efforts by noting that the senator's "explanations explanatory of explanations explained are interminable." But when given the opportunity to speak in New York City, Lincoln was at pains to construct his own argument giving Republican beliefs the imprimatur of the Founders. He opened the Cooper Union address by accepting Douglas's premise that "Our fathers" who "framed the Government under which we live," understood "this question" best and proposed to fight on the very ground that Douglas had laid out. Lincoln identified the fathers, or framers, as the men who signed the Constitution. The question was Douglas's: "Does the proper division of local from federal authority, or anything in the Constitution, forbid our Federal Government to control as to slavery in our Federal Territories?" Douglas said yes; the Republicans no. Lincoln sought to prove that the Founders would have agreed with the Republicans, not the Democrats, and he sought to do so by making an historical argument.[42]

The Cooper Union address is perhaps the most consciously historical of Lincoln's speeches. But where Seward and Sumner had discussed history to show the developing policies over slavery in the territories, Lincoln, taking Douglas as his "text," was concerned only with the founding. Douglas returned to the framers to show that popular sovereignty was indeed the great principle of the republic. Lincoln returned to the framers to show it was not. He spent a third to a half of the speech discussing how the thirty-nine signers of the Constitution voted on other measures related to slavery in the territories. When he found them in agreement with modern Republicans, his refrain included Douglas's phrasing from the Harper's article that there was "no line dividing local from federal authority." Since one of the purposes of traveling to New York was to introduce himself to eastern Republicans, the painstaking research behind Lincoln's assertions would make clear to his audience that he was a statesman worthy of presidential consideration, not the "Western Stump Orator" they might have previously thought. Harold Holzer notes that the Cooper Union speech is one of the least quoted because it lacks some of Lincoln's usual rhetorical flair. It is "almost mordantly legalistic and historical."[43]

What is indeed missing from the Cooper Union address is the emphasis Lincoln had previously put on slavery's morality and the slave's humanity. The second section of the speech, addressed to the absent southerners, asserts the harmlessness of the Republican position. It is there that Lincoln denies any affinity with John Brown, who had recently tried to incite a slave rebellion in Virginia. Perhaps as part of an effort to achieve that distance, Lincoln minimized his condemnations of slavery's immorality. He asserts that it is an "evil" so "marked" by those original framers. He notes that the Constitution does not use the word slave, and that when it refers to slaves the word "person" is used. But the Cooper Union speech lacks Peoria's ringing denunciation of slavery as a "monstrous injustice," its comparison of slavery to a cancer, and its lengthy argument showing "the humanity of the slave." Lincoln insists at Cooper Union that Republicans can only reassure the South if they "cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right," but he does not spend much time making that condemnation himself. [44] Lincoln returned to popular sovereignty at the end of the speech: "Let us be diverted by none of those sophistical contrivances wherewith we are so industriously plied and belabored—contrivances such as groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong ... such as a policy of 'don't care' on a question about which all true men do care...." [45] Lincoln referred, of course, to the middle ground Douglas had offered with popular sovereignty. In his final line, Lincoln called for a repudiation of popular sovereignty in favor of Republican opposition to slavery extension: "LET US HAVE FAITH THAT RIGHT MAKES MIGHT, AND IN THAT FAITH, LET US, TO THE END, DARE TO DO OUR DUTY AS WE UNDERSTAND IT."[46]

Harold Holzer boldly calls the Cooper Union talk "the speech that made Abraham Lincoln president." I will be so bold as to say that it was popular sovereignty that made Lincoln president. Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act and the consequent turmoil in Kansas provided the political setting for Lincoln's return to political prominence. More than that, it was in setting forth his reasons for opposing popular sovereignty that Lincoln articulated many of his central themes: slavery's incompatibility with republicanism, its immorality, and the threat of a "middle ground" doctrine about slavery such as popular sovereignty to republican liberty. Other Republicans also expressed a moral distaste for slavery and the fear that black slavery threatened white liberty. But they more often used the events in Kansas to indict popular sovereignty as policy. Lincoln concentrated on popular sovereignty as principle. This seemingly left him closer in perspective to Douglas than to his fellow Republicans, but it also meant that Lincoln attacked the very essence of popular sovereignty while other Republicans attacked only its effects. As Lincoln consistently noted, popular sovereignty attached no moral stigma to slavery. Lincoln's concentration on what at Cooper Union he mocked as "the 'gur-reat purrinciple'" of popular sovereignty allowed him to assert the true principle of the republic: freedom. [47]

Notes

-

Robert W. Johannsen, ed., The

Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1965), 199.

-

Robert W. Johannsen, The Frontier,

the Union and Stephen A. Douglas (Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 1989), 228–48.

-

Don E. Fehrenbacher, Prelude to

Greatness: Lincoln in the 1850's (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford

University Press, 1962), 19–47; Richard J. Carwardine,

Lincoln (Edinburgh: Pearson Education, 2003), xiv,

24–28.

-

William Lee Miller, Lincoln's

Virtues: An Ethical Biography (New York: Knopf, 2002),

234–37; Lincoln to Joshua F. Speed, August 24, 1855, Roy P.

Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln,

9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Presss,

1953–1955) 2:320; Johannsen, Lincoln-Douglas Debates,

199; David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861

(New York: Harper & Row, 1976), 121.

-

Congressional Globe, 33 Cong., 1st

sess. (Washington, D.C., 1854), 281–82; Nicole Etcheson, "The

Great Principle of Self-Government: Popular Sovereignty and

Bleeding Kansas," Kansas History 27 (Spring–Summer

2004): 14–29.

-

David Herbert Donald, Lincoln

(New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 58, 119, 124–26,

132–33, 137–42, 154–57, 164, 173–78, 181,

189–92; Miller, Lincoln's Virtues, 216–21;

Carwardine, Lincoln, 9–10; Lincoln to Joshua F. Speed,

August 24, 1855, Collected Works, 2:322–23. Lincoln

was a senatorial candidate in 1855 and 1858. In 1856 his name was

floated as a possible vice-presidential candidate on the Republican

ticket that nominated John C. Frémont. In 1860 he was elected

president in a field that included Douglas as nominee of the

Northern Democrats. Donald, Lincoln, 179–85, 193;

Lincoln to Elihu B. Washburne, February 9, 1855, Collected

Works, 2:304–6.

-

Lerone Bennett Jr., Forced into

Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream (Chicago: Johnson

Publishing, 2000), 298, 300–1.

-

Miller, Lincoln's Virtues, 115.

-

Fehrenbacher, Prelude to

Greatness, 24; Carwardine, Lincoln, xiv; John Channing

Briggs, Lincoln's Speeches Reconsidered (Baltimore, Md.:

Johns Hopkins Press, 2005), 134; James Tackach, Lincoln's Moral

Vision: The Second Inaugural Address (Jackson: University of

Mississippi Press, 2002), 10–11; Lincoln to Jesse W. Fell,

December 20, 1859, Collected Works, 3:512; Autobiography

Written for John L. Scripps [ca. June 1860], ibid., 4:67.

-

Miller, Lincoln's Virtues,

248–49; Fragment on Stephen A. Douglas [Dec. 1856],

Collected Works, 2:382–83; Lincoln to John M. Palmer,

September 7, 1854, ibid., 228.

-

Johannsen, Lincoln-Douglas

Debates, 48; Speech at Peoria, October 16, 1854, Collected

Works, 2:274; Donald, Lincoln, 232–33; Miller,

Lincoln's Virtues, 238; Speech at Bloomington, September 26,

1854, Collected Works, 2:239. See also David Zarefsky,

Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery: In the Crucible of Public

Debate (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990),

172–88.

-

Carwardine, Lincoln, 25; Speech

at Peoria, October 16, 1854, Collected Works,

2:247–83.

-

Douglas argued that the Compromise of

1850 had already abrogated the 1820 Compromise. Ibid.,

248–54; Congressional Globe Appendix, 33 Cong., 1st

sess. (Washington, D.C., 1854), 150–55, 768–70.

-

Speech at Peoria, October 16, 1854,

Collected Works, 2:255–56, 260–61, 264–66.

-

Ibid., 271.

-

Ibid., 270–71, 274–76.

-

Wendell Holmes Stephenson, The

Political Career of General James H. Lane (Topeka, Kan.:

Walker, 1930), 42.

-

Lawrence (Kansas) Herald of

Freedom, July 7, 1855.

-

Congressional Globe Appendix, 34

Cong., 1st sess. (Washington, D.C., 1856), 535.

-

Ibid., 535–43.

-

Ibid., 543–44.

-

Speech at Springfield, June 26, 1857,

Collected Works, 2:399–400.

-

Stephenson, General James H.

Lane, 73; W.F.M. Arny to Lincoln, July 16, 1856, folder 7,

Lyman Trumbull Family Papers (Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library,

Springfield, Ill.); Carwardine, Lincoln, 63; Lincoln to

Joshua F. Speed, August 24, 1855, Collected Works,

2:320–21.

-

Nicole Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas:

Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (Lawrence: University

Press of Kansas, 2004), 139–67.

-

Robert W. Johannsen, Stephen A.

Douglas (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997),

610–15; Speech at Chicago, July 10, 1858, Collected

Works, 2:489–90; Speech at Springfield, July 17, 1858,

ibid., 510; Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery,

42–43; Donald, Lincoln, 202–5, 212–13;

Robert W. Johannsen, "Stephen A. Douglas, 'Harper's Magazine,' and

Popular Sovereignty," Mississippi Valley Historical Review

45 (March 1959): 606–31, 611; Fehrenbacher, Prelude to

Greatness, 78; Jeffrey Leigh Sedgwick, "Abraham Lincoln and the

Character of Liberal Statesmanship," in Legacy of Disunion: The

Enduring Significance of the American Civil War, ed. by

Susan-Mary Grant and Peter J. Parish (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 2003), 100–15, especially 102.

-

While he did not explicitly use the

house divided metaphor, William Henry Seward spoke of "an

irrepressible conflict" whose ultimate result would be "that the

United States must and will, sooner or later, become either

entirely a slaveholding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation."

William Henry Seward, "On the Irrepressible Conflict," October 25,

1858, http://www.nyhistory.com/central/conflict.htm. (accessed November 1, 2006). John Channing Briggs

argues that Lincoln sought both to steer Republicans away from

acceptance of popular sovereignty and differentiate himself from

Seward in the "House Divided" speech. Lincoln's Speeches

Reconsidered, 170–71.

-

Johannsen, Lincoln-Douglas

Debates, 14–15, 18–19, 55.

-

Donald, Lincoln, 206–9,

221; Johannsen, Lincoln-Douglas Debates, 58–59,

166–76. See Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery,

80–110.

-

Johannsen, Lincoln-Douglas

Debates, 79; Donald, Lincoln, 218–19.

-

Johannsen, Lincoln-Douglas

Debates, 145–47.

-

Ibid., 280–81.

-

Ibid., 199–200.

-

Ibid., 309–10.

-

Donald, Lincoln, 228;

Carwardine, Lincoln, 85; Lincoln to Anson G. Henry, November

19, 1858, Collected Works, 3:339.

-

Lincoln to Samuel Galloway, July 18,

1859, Collected Works, 3:394–95; Speech at Columbus,

September 16, 1859, ibid., 421–23.

-

Speech at Cincinnati, September 17,

1859, ibid., 442–46.

-

Ibid., 454–58; Speech at

Leavenworth, December 3, 1859, ibid., 498; Speech at Indianapolis,

September 19, 1859, ibid., 467–68.

-

Lincoln to Schuyler Colfax, July 6,

1859, ibid., 390–91.

-

Speech at Elwood, Kansas, December 1

[November 30?], 1859, ibid., 495–96; Speech at Leavenworth,

December 3, 1859, ibid., 497–502.

-

Speech at Chicago, March 1, 1859,

ibid., 365–70; Speech at Cincinnati, September 17, 1859,

ibid., 461.

-

Harold Holzer, Lincoln at Cooper

Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President (New

York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 35; Johannsen, "Douglas,

'Harper's,' and Popular Sovereignty," 607–10, 613, 616.

Douglas even equated southern arguments that slavery could not be

kept out of the territories because they were the common property

of all states with what he claimed was the British government's

insistence that Virginia must have slavery because "the colonies

were the common property of the Empire." Stephen A. Douglas, "The

Dividing Line between Federal and Local Authority: Popular

Sovereignty in the Territories," Harper's New Monthly

Magazine, September 1859, 519–37, especially

521–24, 527–28, 530–37.

-

Quoted in Johannsen, "Douglas,

'Harper's,' and Popular Sovereignty," 624; Holzer, Lincoln at

Cooper Union, 119–30, 252–53. Lincoln had developed

some of the ideas he would use at Cooper Union in his speech at

Columbus, Ohio. Speech at Columbus, Ohio, September 16, 1859,

Collected Works, 3:400–25.

-

Address at Cooper Institute, February

27, 1860, Collected Works, 3:522–50; Holzer,

Lincoln at Cooper Union, 224–26, 233, 252,

254–66.

-

Holzer, Lincoln at Cooper

Union, 267–78, 281; Speech at Peoria, October 16, 1854,

Collected Works, 2:255, 274, 264–65.

-

Address at Cooper Institute, ibid.,

3:550.

-

Ibid.

-

Holzer, Lincoln at Cooper

Union, 269.