Sculptural Commemorations of Abraham Lincoln by Avard T. Fairbanks

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): Copyright © Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. For permission to reuse journal material, please contact the University of Illinois Press (UIP-RIGHTS@uillinois.edu). Permission to reproduce and distribute journal material for academic courses and/or coursepacks may be obtained from the Copyright Clearance Center (www.copyright.com).

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Lincoln Landscape

Illinois residents proclaim their state to be the Land of Lincoln. The 2003 commemorative quarter for Illinois features an image of a young Abraham Lincoln holding a law book in the right hand while laying aside an ax with the other hand. The image is based on a famous statue that stands outside the visitor center at Lincoln's New Salem State Historic Site near Petersburg, twenty miles northwest of the state capital. The statue is the creation of sculptor-historian Avard T. Fairbanks. It is one of a dozen important Lincoln-themed sculptures that Fairbanks completed during his productive career. Fairbanks had an affinity for Lincoln. Through his sculptures he created a commemorative Lincoln landscape that extends beyond the prairies of Illinois and the pillared buildings of the nation's capital.[1]

In his youth, Fairbanks lived for two years on the frontier with his family in a one-room lean-to cabin while homesteading on the prairie of Alberta, Canada. He lost his mother in childhood, as did Lincoln, and missed her guiding influence. "Because I am of pioneer descent and have experienced the frontier during my own childhood," he wrote, "the traditions of Lincoln have been very much a part of my early training." He related to the youthful rough-hewn frontier Lincoln who dreamed of improving conditions for himself and others. As the years passed, Fairbanks became professionally preoccupied with heavy teaching schedules, demonstration lectures, and commissions for portraits and fantasy statuary.[2] Still, the desire to create a Lincoln-themed sculpture lingered. Finally, after several decades, an opportunity unexpectedly arose.

Lincoln the Frontiersman, Ewa Plantation School, Ewa, Hawaii. Dedicated February 12, 1944

While teaching summer school at the University of Hawaii in 1939, this forty-two-year-old professor of fine arts came to the attention of a committee seeking a sculptor to create a Lincoln statue for the Ewa Plantation school pursuant to a bequest by a former teacher and principal, Katherine Burke. Burke's estate was small. Other sculptors had declined the project, as the pay was insufficient. But when an unsolicited invitation came to Fairbanks in spring 1940 after he had returned to his academic post at the University of Michigan, he was intrigued by the opportunity despite the tight budget. How, he wondered, could an appropriate statue of Lincoln be created for a tropical island paradise?

One day in June, after university classes were over, he received a call that his ailing father was dying. He hurried to his father's home but was too late. While awaiting the funeral, he pondered the Lincoln statue. "My first impression was to make a statue of Lincoln in his frock coat as the President of the United States," he later recalled. "The long lines of the trousers and the coat seemed rather appealing from just the standpoint of the lines." Another thought was Lincoln with a shawl, but Fairbanks decided that would never do for the semitropical climate of Hawaii. Then he considered the hopes of the schoolteacher benefactor, Katherine Burke, and her desire to inspire students. "To make him as a youth seemed to gain the attention of my thoughts," he said.

One day while still in mourning at his father's farm, Fairbanks took an ax and went into the field to clear some old trees and stumps. As he worked, he thought of the Lincoln statue. As a youth Lincoln had used an ax. He had experienced sorrows and hopes. He was strong and he could work well. He worked with a purpose, and he cleared the fields and forests for new growth and new developments. As he developed strong in body, he also was developing strength in character and mind. He had to cut his way through.... He was a frontiersman! "It was there," Fairbanks later said, "that the inspiration of Lincoln as a youthful frontiersman, with an ax in hand, came to me."

Fairbanks returned to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and set about making sketches of the idea, first on paper and then in small bits of clay. He submitted the sketches to the committee in Hawaii. He also presented a demonstration lecture to the Detroit Lincoln Group, the nearest Lincoln association, to seek their input. During a discussion of sculpture details and historical background, he molded a two-foot-tall statuette. The concept of a young Lincoln, a figure in action, for a school in a relatively young territory in the Pacific, a frontier, was received with enthusiasm.[3] There were many portrayals of Abraham Lincoln, but few if any depicted him as a frontiersman, a neglected period of his life.

Fairbanks sent photographs and sketches of the proposed monument to the committee in Hawaii. They were pleased with the plans. He then made a four-foot-tall model cast. Again it met with committee enthusiasm. With that approval, he began the heroic, nine-foot-tall statue. He preferred the heroic size—one-and-a-half scale—because life-size figures on a pedestal appeared too small. Fairbanks began using an abandoned auditorium in one of the oldest campus buildings at the University of Michigan as a studio. The beams were calculated to be able to support the weight of armature, clay, plaster of the cast, and of the mold. Work progressed after classes, evenings, and on weekends. The final model was completed in June 1941 and went on display during the week of university commencement exercises and alumni sessions. A visiting member of the Hawaiian committee gave final approval, and casting in plaster began within days. Newspaper publicity of the project brought national attention. A critic declared that Fairbanks had "put America in Abraham Lincoln as few other artists have ever done." Fairbanks made him "powerful, alert, aggressive," and with eyes through which Lincoln visualized far ahead to the blessings of "a free and united nation."

The making of the mold and the cast took a large part of the summer. Finally, the cast was complete but in sections. It was boxed and sent to the Roman Bronze company, a foundry in Corona, New York. World War II was raging in Europe, and there was concern that restrictions on non-military uses of copper, a major ingredient of bronze, would stall the project. But late that year the statue was cast before restrictions were placed. Delivery of the statue to Hawaii was delayed by the Pearl Harbor attack, as only high-priority cargo was allowed to be shipped. It was not sent until 1943. The heroic bronze monument was erected on a base of rainbow granite, and the dedication was arranged for February 12, 1944, the 135th anniversary of Lincoln's birth ( Figure 1). It was an important day for the Ewa school, the city of Ewa, and the island of Oahu.[4]

The Ewa school is justly proud of its Lincoln statue. It has often received favorable public attention. A February 12 tradition at the school is a patriotic celebration during which fragrant, flowery leis are placed over the Lincoln monument's shoulders to express of the spirit of Aloha. The spirit of Lincoln the Frontiersman continues to permeate the school and islands.

Lincoln Statue for New Salem, Lincoln's New Salem State Historic Site, Petersburg, Illinois. Dedicated June 21, 1954

Following World War II the University of Utah was expanding, and officials invited Dr. Fairbanks to become the first dean of the College of Fine Arts. As dean he initiated a comprehensive program of art studies, including graphics, painting, sculpture, art anatomy, art history, music, dance, and industrial applications. He deferred his own creative endeavors for several years while attending to administrative duties. An opportunity developed when the Sons of the Utah Pioneers, a history-oriented association, chose to honor Abraham Lincoln by commissioning a sculpture befitting one of the nineteenth-century's greatest Americans. Although their Mormon ancestors had been driven from Illinois during Lincoln's lifetime, association members maintained a sense of respect for the principles and life of the sixteenth president.

At New Salem, a young, relatively uneducated Abraham Lincoln had worked in several capacities—as a store clerk, postmaster, surveyor, and soldier. There he began his study of law, cast his first vote, and entered into politics. The State of Illinois acquired the old town site in 1919, and in the 1930s workers restored portions of it as a state historical park and as a memorial to Lincoln. But it had no Lincoln statue. When the Sons of the Utah Pioneers decided to sponsor an appropriate Lincoln sculpture for the site, they sought the help of one of its members, Avard Fairbanks. As a student of Lincoln's life and one who empathized with the future president's trials and capacity for growth and self-improvement, Fairbanks was delighted for another opportunity to interpret the man—"to bring to the people of America this phase of the determining years of his life."

"To make a suitable statue of such a subject," Fairbanks later wrote, "one must first get in mind a basic concept of the character to be portrayed. The spirit of the times has to be sensed." The statue's location was another defining factor. "A memorial should be made in size commensurate with the personage who has achieved eminence and has performed heroic deeds," Fairbanks believed. "Therefore a statue that would look well in a public park or public building should be of heroic size, eight or nine feet high. A life size statue placed in the open gives the impression of a small man, and such a statue in no way would characterize Lincoln."

Fairbanks reported that he devoted much time to making different studies of the head of Lincoln as he appeared at the age of twenty-eight—the age when he left New Salem to practice law in Springfield. He obtained reproductions of Lincoln's life masks and his cast hands. [5] In the New Salem sculpture, Fairbanks portrays Lincoln as tall, broad shouldered, and courageous. He gave him deep and far-seeing eyes. "His whole attitude of mind is displayed by looks outward and forward, as if clearly foreseeing a significant destiny for himself and his fellow men," Fairbanks explained. A Detroit writer found the "New Salem Lincoln" to be similar to the "Hawaiian Lincoln" of a decade earlier, but with some important differences. "Both boots and the ax are the same, and the clothing is similar; but the countenance is more mature," he noted. The ax that in the Hawaiian sculpture was held firmly in both hands in a working position, in the New Salem sculpture instead rested on the ground with the handle supported loosely in Lincoln's left hand, while the right arm firmly clutched a heavy law book. Fairbanks had succeeded in capturing in bronze a transitional moment that symbolized Lincoln at New Salem: "the laying down of the ax and taking up the law books; the transition of the rail-splitting frontiersman into the young lawyer."

After many trials of one study and another, Fairbanks developed a preliminary one-third-life-size model. From this he constructed a two-thirds-life-size working model, and then finally the heroic nine-foot model. He sent a plaster cast of the final version in sections to the Roman Bronze foundry, which cast the bronze statue. At New Salem a base of rainbow granite was prepared. "God gave to man the rainbow in the heavens as a symbol of hope and promise," Fairbank's declared ( Figure 2). "A statue of Abraham Lincoln in bronze on a base of rainbow granite—the most imperishable materials of the earth—shall be symbolic, for the peoples of the world, of these enduring hopes and promises to be gained through adherence to those guiding principles given by Lincoln." On the granite base was inscribed a quotation from Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address: "With malice toward none, with charity for all."

In the dedicatory speech at New Salem on June 21, 1954, Bryant S. Hinkley stated: "We unite with you and all America in honoring Illinois' great citizen and one of the greatest leaders of all times. Majestic in character and intellect, lofty in purpose, sublime in his faith and forgiveness, Abraham Lincoln stands as the tenderest memory of all the ages." Avard Fairbanks would be proud if he could see his New Salem Lincoln featured on the Illinois commemorative quarter.

The Chicago Lincoln, Lincoln Square, at the confluence of Lincoln, Lawrence, and Western Avenues, Ravenswood, Chicago's North Side. Dedicated October 16, 1956

The Lincoln monuments in Hawaii and New Salem resulted in considerable notoriety for Fairbanks. In his research efforts he had met and become friends with many Lincoln scholars. He was soon sought to create other masterpieces. There were many statues of Lincoln across the Illinois landscape. Yet, at Lincoln Square—a broad intersection of important thoroughfares on Chicago's North Side that had been named in honor of the president—there was no monument. Alderman John Hoellen of the 47th Ward deserves credit for conceiving the idea for a Lincoln statue at this site. He proposed it to the chamber of commerce and kept promoting it. Other community leaders joined in, and the editors of the Lerner Chicago Northside Newspapers actively promoted the proposal. A memorial commission was formed. The legislature passed a bill and Governor William G. Stratton signed it. With appropriations from the state legislature, commission members searched for a sculptor. They chose Avard Fairbanks.

This time Fairbanks interpreted an older Lincoln at the pinnacle of an Illinois political career that had brought him to the brink of leadership in the highest councils of the land. The statue would capture Lincoln's aspiring to the presidency of the United States. For his theme Fairbanks took words from a speech Lincoln delivered in Chicago in December 1856. He also found inspiration in Lincoln's biblical allusion—"A house divided against itself"—from the famous "House Divided" speech delivered at the statehouse in Springfield, Illinois, at the commencement of his Senate campaign against Stephen A. Douglas in 1858. "Can you sense both the anxiety of Lincoln and the nation in his time?" Fairbanks asked. "To feel the magnitude of Lincoln's aspiring to the position of President, one has to sense the struggles and the possible reactions Lincoln might have felt, and how his whole being might have been tense to the situation."

Again the artist faced the by-now-familiar task, as Fairbanks expressed it, of giving "soul and spirit to form so that it lives on." All external details had to be correct. Particular proportions of the person, the mannerisms, the costume—all required authenticity. But ultimately it was, as Fairbanks acknowledged, "the inner soul and spirit" of his subject that "must be known and expressed."

Consulting with Ralph G. Newman, proprietor of the Abraham Lincoln Book Shop in Chicago, Fairbanks learned that the pose he projected for Lincoln in the new sculpture had been previously used in a statue by another sculptor. So instead of extending Lincoln's arm in the air as planned, he placed a podium on Lincoln's right with his hand firmly gripping the draping cloth. As the work progressed it became more vigorous and strong.

After approval by the commission, the heroic statue was cast first in plaster and then in bronze ( Figure 3). The spirit of Abraham Lincoln captured in bronze was placed on a rainbow granite pedestal inscribed with a quotation from the December 1856 Chicago speech: "Free society is not and shall not be a failure." Fairbanks considered it "a constant testament to the world of his greatness and his faith in humanity." It was dedicated in a magnificent ceremony on October 16, 1956, with bands playing, flags waving, and with community supporters and many notable state and city officials participating.

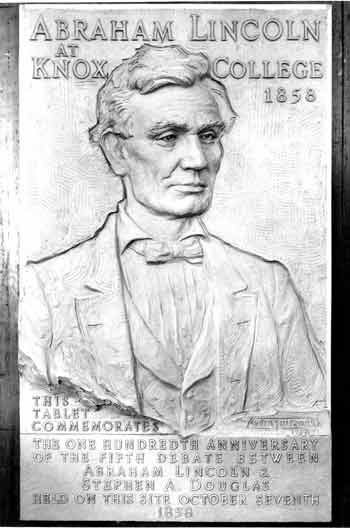

Lincoln and Douglas Bas-Relief Panels, Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois. Dedicated October 6, 1958

Fairbanks's next Lincoln project involved a Lincoln-Douglas debate theme. In anticipation of the centennial commemoration of the historic debates, officials in Galesburg, Illinois, commissioned Fairbanks to create two bas-relief panels to adorn the front of Old Main at Knox College, the location of the fifth of the seven debates, on October 7, 1858. Lincoln was a foot taller than the "Little Giant." So, for these panels Fairbanks chose to portray Abraham Lincoln with his head higher on the plaque in order to convey the impression of his tall stature. Douglas's face is nearly centered. They partly face each other, yet look out as though ready to speak. These two great statesmen had succeeded as national leaders by outstanding ability, tenacious determination, diligent application, and heroic effort. Fate was unkind to them indeed, for neither survived a decade following the debates.

Knox College had hosted previous anniversaries—the thirty-eighth in 1896 and the seventieth in 1928, which attracted ten thousand people including forty who had attended the original debate. The 1958 celebration began October 4 and lasted for several days. It was the product of a joint effort by Knox College, Galesburg officials, the Illinois State Historical Society, and many other organizations. October 6 was designated Carl Sandburg Day in honor of Galesburg's native son, who had attended Knox College and went on to become a noted poet, editor, historian, and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of a multi-volume Lincoln biography.[6] But it was the unveiling and dedication of the Lincoln and Douglas bas-relief panels that made an impressive climax to the commemorative events of the day ( Figures 4 and 5). The following day, October 7 (the anniversary of the debate), with the new bas-reliefs providing a fitting backdrop, the popular Civil War historian Bruce Catton delivered a centennial convocation address. Illinois Governor William Stratton discussed the debates. Republican Senator Everett Dirksen spoke about Abraham Lincoln, while Democratic Senator Paul Douglas spoke about Stephen A. Douglas.

The Knox College Old Main building stands today, much as it did a century and a half ago. The commemorative panels, cast in bronze, have been permanently mounted on the building. They portray not only the personages, but also the moment, the feeling of the men, and the impact of the event.

Lincoln the Friendly Neighbor, Lincoln School, Berwyn, Illinois. Dedicated July 4, 1959 (Rededicated 1997)

When planning a new building for the Lincoln Federal Savings and Loan Association of Berwyn, Illinois, Frank Kinst, the bank president, wanted to make it a suburban showplace. He consulted with Ralph Newman of the Abraham Lincoln Book Shop and arranged to commission Avard Fairbanks to create a colossal sculptural portrait bust of Abraham Lincoln for the bank lobby. He also commissioned a Lincoln statue to be placed in front of the new bank.

With the concurrence of the bank's board of directors, Kinst, Newman, and Fairbanks decided to portray Lincoln as a friendly neighbor. Fairbanks chose as a theme a phrase from a letter Lincoln wrote to an Illinois friend, Judge Joseph Gillespie: "The better part of one's life consists of his friendships." This statement suggested to Fairbanks a warm interest in the life of the community, especially the children. "In the statue, Lincoln places his great hand upon the shoulder of youth as if on every young boy in our country, in every walk of life, and in every activity," Fairbanks explained (Figure 6). "Thus, symbolized in bronze, his guiding hand inspires every boy to greatness in the field he will choose for the future." Regarding the figure of the young lady looking up at Lincoln as she grasps his arm, the sculptor remarked, "There must be someone to guide our people in times of stress and dissension. Such is her expression of confidence in this great man. Her countenance represents the trust, the hope, and the admiration of America."

It took two years to complete the project. The unveiling ceremony was held July 4, 1959, in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth. Paul H. Douglas, U.S. senator from Illinois delivered the dedicatory speech. A host of other dignitaries participated. Later the bank changed owners and name. The Lincoln statue standing outside the bank's doors was considered no longer appropriate, and it was given to a new Lincoln School constructed at 16th and Elmwood streets in Berwyn. The statue was rededicated in 1997.

The Enduring Lincoln, private owner. Dedicated July 4, 1959

Fairbanks had not neglected the sculptural portrait that Kinst had commissioned for inside the bank lobby. He had often desired the opportunity to create a large bust of Abraham Lincoln as president. For this project he chose to portray Lincoln in contemplation, in a moment of reflection, externally calm, but inwardly seeking a solution to the many momentous problems of his time. Fairbanks created a model that he entitled The Enduring Lincoln. It was approved and a cast sent to Pietrasanta, Italy, where skilled carvers cut a much larger portrait in fine white Cararra marble to an accuracy of within 1/64th inch. Fairbanks flew to Italy to complete the carving and finish the details, especially the expression of the face ( Figure 7). The colossal marble, three times life size, was then crated and shipped to Illinois. It arrived the day before the dedication of the outdoor statue on July 4. With some great effort it was installed in time for the dedication. It remained on display in the bank for several years afterwards. When the bank changed names and ownership, the masterpiece was deemed inappropriate and was sold to a private party.

The Four Ages of Lincoln, Ford's Theatre and the U.S. Supreme Court, Washington, D.C. Dedicated February 11, 1960

In anticipation of the sesquicentennial celebration of Abraham Lincoln's birth, Broadcast Music, Inc. of New York City, invited more than seventy-five fine writers and distinguished Americans to contribute to radio addresses about Lincoln's impact on the world. The radio script, entitled "Abraham Lincoln 1809–1959," was to be part of the company's prize-winning series, The American Story. On the recommendation of Ralph G. Newman and several other Lincoln scholars, the company requested Avard Fairbanks to submit sketches of Lincoln busts as illustrations for the project. On seeing the sculptor's drawings, the company commissioned him to create four portrait busts that Fairbanks collectively named the Four Ages of Lincoln.[7]

The first portrait in the series—Lincoln, the Youth—Fairbanks sketched and modeled following a comprehensive study of books and articles relating to Lincoln's boyhood experiences ( Figure 8). The earliest known photograph of Lincoln shows him at about thirty-seven years of age. By expert knowledge and observation of changes in maturation, Fairbanks used Lincoln's features but softened them; his brows and nose were less prominent, the cheeks were rounded, and wrinkles were eliminated. The pleasantness of Lincoln's countenance reflects many of the qualities of his action and personality, yet the vigor of youth is manifest.

The next portrait, Lincoln, the Frontiersman, recalls the monument erected at Ewa Plantation school, Hawaii (Figure 9). Before modeling this portrait, Fairbanks again reviewed much of the research material collected and used during the creation of the first statue. So that he could better mold animation and expression of the subject into lifeless clay, Fairbanks studied additional history to increase his familiarity with the background, character, and experiences of Abraham Lincoln.

The creation of the third portrait, Lincoln, the Lawyer, required considerable research by the sculptor to develop an appreciation of Lincoln's character as he served in courts of law (Figure 10). Fairbanks studied many descriptions of Lincoln's conduct in court. He considered anecdotes by acquaintances and reviewed photographs. He read much Lincoln lore, often re-reading it aloud at the studio in the evening, in order to better understand the feelings and the motivations, thereby modeling Lincoln's personality into clay. Observers of the portrait unconsciously assume the position of juryman, witness, or judge. One may then sense the spirit of the tall, personable, friendly, and often witty but astute advocate as he would plead a case.

During extensive study for the fourth portrait, Lincoln, the President, Fairbanks considered various moods of Lincoln. At length he chose to model him in a moment of reflection, of deep thought, of pondering the evidence for a far-reaching decision, or deliberating on the problems of the army, or easing the burdens of an individual soldier ( Figure 11). He was saddened by the countless casualties of dead and wounded. A genuine humility and compassion were to be molded into the face. The sight of the sick and wounded in hospitals that he visited in Washington, D.C., was a source of heartfelt sorrow. He visited wards as often as he could, giving friendly greetings, showing his genuine interest in the welfare of soldiers of both North and South. This sensibility and sympathy for the suffering Lincoln was set forth in his Second Inaugural Address: "Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away." During these times consumed with sorrow, he once said, "I think I shall never be glad again." Capturing this pathos, the sculptor added age to the face of Abraham Lincoln by cutting in wrinkles a little deeper. Into the marble he carved a sense of grief, softened by a hope for peace.

The Broadcast Music Corporation presented the portrait busts of The Four Ages of Lincoln to the United States government at the Lincoln Day dinner at the Willard Hotel sponsored by the District of Columbia Lincoln Group. The chairman of the national Sesquicentennial Commission accepted the portraits on behalf of the nation. Three of the portraits were placed in the museum at Ford's Theatre where Lincoln had been assassinated ninety-five years earlier. One portrait, Lincoln, the Lawyer, was placed instead at the United States Supreme Court Building, where it is now on permanent exhibition. A heroic copy in Cararra marble of the portrait bust Lincoln, the Frontiersman was placed in a hall of the International Copyright Bureau in the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland.

The Life of George Washington: An Inspiration to Young Abraham Lincoln (medallion struck in commemoration of American Bicentennial, 1976), location of original casting unknown

This medallion, commissioned in connection with the bicentennial celebration in 1976, commemorates the life of George Washington, his devotion to his country and to the cause of liberty, and his serving as an inspiration to young Abraham Lincoln and to all Americans ( Figure 12). Fairbanks portrayed young Lincoln as exhilarated by stories of heroic deeds while reading the inspiring text of Mason Locke Weem's The Life of George Washington before the dim light of a crackling fire on the hearth of a frontier log cabin. In the background an image of General Washington rises in the vapors, and wisps of smoke above the blaze, as though rendering counsel and guidance.

The creation of the medallion was sponsored by Hamilton-Hallmark Mint. The location of the original casting is not known.

Abraham Lincoln of the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln Junior High School, Salt Lake City, Utah. Dedicated February 12, 1965 (Relocated)

In 1964 Avard Fairbanks was requested to create a portrait bust of Abraham Lincoln for Lincoln Junior High School in Salt Lake City, Utah. For this project he chose to portray the president while composing the Gettysburg Address (Figure 13). An illustrious scholar, Dr. Edward Everett, had been invited to give the main dedication address at the Gettysburg Cemetery in November 1863. Lincoln was, with apologies, kindly asked to give only "a few words." Fairbanks portrayed Lincoln in a moment of meditation, composing the manuscript with a quill pen, common in those days. He is modeled with a sense of inspiration, tempered by sorrow as he condenses his thoughts on the Civil War. The sculpture was dedicated on February 12, 1965. The Lincoln Junior High School has since been decommissioned, but the portrait bust may still be viewed at the Fairview Museum in Fairview, Utah.

Abraham Lincoln, the Legislator, United States Capitol Building, Washington, D.C. Dedicated November 11, 1985

One of Avard Fairbank's most impressive depictions of Abraham Lincoln is a colossal portrait carved in Portuguese rose marble interpreting him as a legislator (Figure 14). This three-times-life-size portrait bust shows Lincoln looking up a little as if preparing to debate an issue. Lincoln served four terms (1834–42) as a member of the House of Representatives in the Illinois General Assembly and one term in the United States House of Representatives as a congressman from Illinois' Seventh Congressional District (1847–49). Although there were administrative restrictions on placing new statues in the District of Columbia, Capitol Architect George M. White paved the way for the bust portrait to be placed in the foyer of the ground-level entrance to the chamber of the House of Representatives. It was dedicated on November 11, 1985, at a ceremony attended by numerous congressional dignitaries. Utah Senator Orrin Hatch declared, "When I look closely at this work of art, I see represented not only the life of our beloved president, Abraham Lincoln, but I also see imprinted in this marble the soul of its creator, the artist Dr. Avard Fairbanks."

Other Locations of Lincoln-Themed Sculpture by Fairbanks

Copies of Fairbank's distinct Lincoln sculptures can be viewed at several locations across the country. A colossal portrait bust copy of Lincoln, the Frontiersman was erected at the Lincoln High School in Seattle, Washington in 1964 (Figure 15). A copy of the colossal portrait bust of Lincoln, the President has been placed as a companion piece to a colossal portrait of General George Washington at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Another colossal portrait is at the Springville Museum in Springville, Utah. A portrait of Abraham Lincoln and a four-foot model of Lincoln Statue for New Salem are on display at the Lincoln Museum at Fort Wayne, Indiana. Plaster casts of the Chicago Lincoln and the bas-relief panels of the Lincoln-Douglas debates are exhibited at the Fairview Museum in Fairview, Utah.[8]

For his contributions to Lincolniana, Avard T. Fairbanks received honor and praise. He was awarded the Lincoln Diploma of Honor by Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee; an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Lincoln College, Lincoln, Illinois; and the Lincoln Medal of the Sesquicentennial Commission of the Congress of the United States. He died in January 1987, just two months short of his ninetieth birthday, having created many exceptionally moving and inspirational commemorative Lincoln statues found today in the United States and beyond.

Notes

-

The source of all information and quoted

material in this article, unless otherwise indicated, comes from

the author's book, Abraham Lincoln Sculpture Created by Avard T.

Fairbanks (Bellingham, Wash.: Fairbanks Art and Books, 2002).

-

Avard Tennyson Fairbanks was born in March

1897, the tenth of eleven children. As a boy he was awarded

scholarships to study at the Art Students League in New York City,

and he displayed his sculpture in the National Academy of Design

when he was only fourteen years old. Next he studied in Paris at

several premier art academies. But the outbreak of World War I

interrupted his studies, and he returned to his home in Salt Lake

City to complete high school. At age nineteen he traveled to the

Hawaiian Island of Oahu to work on the Latter-day Saint Temple at

Laie, creating more than a hundred figures on four friezes placed

at the temple cornices. He returned home to attend the University

of Utah and in 1920 accepted a position to teach sculpture at the

University of Oregon. In 1924 he earned a degree at Yale University

and continued teaching at Oregon until 1927, when he was awarded a

Guggenheim fellowship that permitted him to return to Europe for

further study. He returned to the U.S. in 1928 and taught at the

Seattle Institute of Art and earned a master's degree at the

University of Washington in 1929. That same year he joined the

faculty at the University of Michigan and helped to establish its

Institute of Fine Arts. While teaching at Michigan during the 1930s

he earned master's and doctorate degrees in anatomy from the

university's medical school. In 1947 Fairbanks was appointed Dean

at the University of Utah and was charged with organizing a College

of Fine Arts at that institution. In 1965 he went to the University

of North Dakota to close out his academic career as Special

Consultant in Fine Arts and Resident Sculptor for two years. In

retirement he continued a busy and productive schedule creating

commissioned works of art until the very end of his life in January

1987.

-

Tom Starr, president of the Detroit group and

a Lincoln scholar, became a volunteer consultant and a valuable

source of research information. Other investigation was done at the

Albert H. Greenly Lincoln collection of the William L. Clements

Library at the University of Michigan. Several museums were visited

for additional details. Original copies of the Volk life mask and

hand casts were carefully measured and studied. A special

rail-splitter's ax head—broad and shaped like a

wedge—was studied and included in the composition

-

Participants in the ceremonies included the

Royal Hawaiian Band, the Hawaiian superintendent of public

instruction, the governor of Hawaii, the executor of Katherine

Burke's estate, the manager of Ewa Plantations, sculptor Fairbanks,

the student body, and the school chorus.

-

These casts were made before Lincoln's

election to the presidency by sculptor Leonard Volk. These were

invaluable to Fairbanks because they recorded the shape of

Lincoln's head, features, and hands. The use of the casts along

with photographs gave an opportunity to put into that face and

those hands the vibrant spirit, personality, and character of

Lincoln as a young man.

-

Fairbanks also created a special commemorative

portrait bust of Carl Sandburg. The original plaster cast was given

to the Chicago Historical Society. A bronze cast of the bust was

presented to Knox College by several donors and was unveiled at the

college's 115th commencement.

-

Ralph G. Newman edited an essay collection

based on the Broadcast Music, Inc., project that was published as

Lincoln For The Ages (New York: Doubleday, 1960). Among the

contributions is an article by Avard Fairbanks titled, "The Face of

Abraham Lincoln," pp. 160–65.

-

Other sculptures by Fairbanks with indirect

Lincoln-themes include a heroic portrait bust of Albert Woolson,

the last survivor of the Grand Army of the Republic, who attained

the age of 106 years in 1953. During the modeling sessions the two

men developed a fine friendship. The bust was placed in the Duluth,

Minnesota, city hall, and at the request of the Women's Auxiliary

to the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, a bronze monument

copy was placed in Ziegler's Grove at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.